The Burgholzli Centenary

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Kraepelinian Tradition Paul Hoff, MD, Phd

Clinical research The Kraepelinian tradition Paul Hoff, MD, PhD Introduction n the 21st century, Emil Kraepelin’s views remain a majorI point of reference, especially regarding nosol- ogy and research strategies in psychiatry. However, the “neo-Kraepelinian” perspective has also been criticized substantially in recent years, the nosological dichotomy Emil Kraepelin (1856–1926) was an influential figure in of schizophrenic and affective psychoses being a focus the history of psychiatry as a clinical science. This pa- of this criticism. A thorough knowledge and balanced per, after briefly presenting his biography, discusses interpretation of Kraepelin’s work as it developed along- the conceptual foundations of his concept of mental side the nine editions of his textbook (published between illness and follows this line of thought through to late 1883 and 1927)1 is indispensable for a profound under- 20th-century “Neo-Kraepelinianism,” including recent standing of this important debate, and for its further de- criticism, particularly of the nosological dichotomy of velopment beyond the historical perspective. endogenous psychoses. Throughout his professional life, Kraepelin put emphasis on establishing psychiatry A brief biography as a clinical science with a strong empirical background. He preferred pragmatic attitudes and arguments, thus Emil Kraepelin was born in Neustrelitz (Mecklenburg, underestimating the philosophical presuppositions of West Pomerania, Germany) on February 15, 1856. He his work. As for nosology, his central hypothesis is the studied medicine in Leipzig and Wuerzburg from 1874 un- existence and scientific accessibility of “natural disease til 1878. He worked as a guest student at the psychiatric entities” (“natürliche Krankheitseinheiten”) in psychi- hospital in Wuerzburg under the directorship of Franz von atry. -

Who Was Emil Kraepelin and Why Do We Remember Him 160 Years Later?

TRAMES, 2016, 20(70/65), 4, 317–335 WHO WAS EMIL KRAEPELIN AND WHY DO WE REMEMBER HIM 160 YEARS LATER? Jüri Allik1 and Erki Tammiksaar1,2 1University of Tartu and 2Estonian University of Life Sciences Abstract. In order to commemorate Kraepelin’s 160th birthdate and the 130th year from his first professorship, a conference “Emil Kraepelin 160/130” was held in the same Aula of the University of Tartu where 130 years earlier Kraepelin expressed his views about the relationship between psychiatric illnesses and brain functions. This special issue is composed of talks that were held at the conference. However, papers presented in this special issue are in most cases much more elaborated versions of the presented talks. In this introductory article, we remember some basic facts about Emil Kraepelin’s life and the impact he made in various areas, not only in psychiatry. We also try to create a context into which papers presented in this special issue of Trames can be placed. Keywords: Emil Kraepelin; history of psychiatry and psychology; University of Dorpat/Tartu DOI: 10.3176/tr.2016.4.01 Usually, Emil Wilhelm Magnus Georg Kraepelin (1856–1926) is identified as the founder of modern scientific psychiatry (Decker 2004, Engstrom & Kendler 2015, Healy, Harris, Farquhar, Tschinkel, & Le Noury 2008, Hippius & Mueller 2008, Hoff 1994, Jablensky, Hugler, Voncranach, & Kalinov 1993, Steinberg 2015). However, it took some time to recognize Kraepelin’s other contributions to many other areas such as psychopharmacology (Müller, Fletcher, & Steinberg 2006, Saarma & Vahing 1976, Schmied, Steinberg, & Sykes 2006, Vahing & Mehilane 1990), sleep research (Becker, Steinberg, & Kluge 2016) and psychology (Eysenck & Frith 1977, Steinberg 2015). -

Gudden, Huguenin, Hitzig : Hirnpsychiatrie Im Burghölzli 1869

Gudden, Huguenin, Hitzig Hirnpsychiatrie imBurghölzli 1869-1879 Von Erwin H. Ackerknecht Das Burghölzli, die psychiatrische Klinik der Universität Zürich, begann sich gegen das Ende des 19. und zu Anfang des 20. Jahrhunderts eines internationalen Rufs zu erfreuen. Ihre Direktoren in diesen Jahrzehnten, Auguste Forel und Eugen Bleuler, sind unvergessen. Weniger freundlich ist die Geschichte mit den ersten drei Direktoren Gudden, Huguenin und Hitzig umgegangen, welche die Anstalt von 1870 bis 1879 leiteten. Eine Beschäftigung mit ihnen ist nicht nur gerecht, sondern auch dadurch gerechtfertigt, daß diese drei Männer außerordent- lieh typisch für die dominierende Tendenz der wissenschaftlichen Psychiatrie dieser Zeit sind, die sogenannte Hirnpsychiatrie, welche aus Mangel an histo- rischem Verständnis heute einfach über die Schulter angesehen wird. Die Mehrheit der deutschen Psychiater um 1850 waren noch immer söge- nannte «Irrenväter». Nur wenige Psychiater verfügten über Universitätskliniken. Die meisten lebten in großen und kleinen Anstalten inmitten ihrer Kranken. Die großen Erfolge der Anatomie, Physiologie und pathologischen Anatomie in der Medizin im allgemeinen führten nun die jungen Optimisten, die über diese Irren- väterrolle hinausgehen wollten, auf den Weg der Hirnanatomie, Hirnphysiologie und pathologischen Anatomie des Gehirns h Monakow, selbst ursprünglich Psychiater, weist mit Stolz darauf hin, daß die wesentlichen hirnanatomischen Entdeckungen dieser Zeit nicht von Physiologen und Anatomen, sondern von Psychiatern wie eben Gudden, Hitzig etc. gemacht worden sind*. Gudden (geb. 1824), Hitzig (geb. 1838), Meynert (geb. 1833) oder Westphal (geb. 1833) waren keine episodischen Erscheinungen, sondern die Führer einer Phalanx, zu der auch die zwei letzten Gudden-Schüler Forel (geb. 1848) und Kraepelin (geb. 1856) sowie die Schüler des ersteren E.Bleuler (geb. -

Auguste Forel on Ants and Neurology

MOC Choice www.ccns.org HISTORICAL NEUROSCIENCE Auguste Forel on Ants and Neurology André Parent ABSTRACT: Auguste Forel was born in 1848 in the French part of Switzerland. He developed a lifelong passion for myrmecology in his childhood, but chose medicine and neuropsychiatry to earn his living. He first undertook a comparative study of the thalamus under Theodor Meynert in Vienna and then, from 1872 to 1879, he worked as Assistant Physician to Bernhard von Gudden in Munich. This led in 1877 to his seminal work on the organization of the tegmental region in which he provides the first description of the zona incerta and the so-called H (Haubenfeld) fields that still bear his name. In 1879, Forel was appointed Professor of Psychiatry in Munich and Director of the Burghölzli cantonal asylum. He became interested in the therapeutic value of hypnotism, while continuing his work on brain anatomy and ants. His neuroanatomical studies with Gudden’s method led him to formulate the neuron theory in 1887, four years before Wilhelm von Waldeyer, who received most of the credit for it. Forel then definitively turned his back on neuroscience. After his retirement from the Burghölzli asylum in 1898, and despite a stroke in 1911 that left him hemiplegic, Forel started to write extensively on various social issues, such as alcohol abstinence and sexual problems. Before his death in 1931 at the age of 83, Forel published a remarkable book on the social world of the ants in which he made insightful observations on the neural control of sensory and instinctive behavior common to both humans and insects. -

The Psychiatrist Auguste Forel and His Attitude to Eugenics Bernhard Kuechenhoff

The psychiatrist Auguste Forel and his attitude to eugenics Bernhard Kuechenhoff To cite this version: Bernhard Kuechenhoff. The psychiatrist Auguste Forel and his attitude to eugenics. History ofPsy- chiatry, SAGE Publications, 2008, 19 (2), pp.215-223. 10.1177/0957154X07080660. hal-00570902 HAL Id: hal-00570902 https://hal.archives-ouvertes.fr/hal-00570902 Submitted on 1 Mar 2011 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. History of Psychiatry, 19(2): 215–223 Copyright © 2008 SAGE Publications (Los Angeles, London, New Delhi, and Singapore) www.sagepublications.com [200806] DOI: 10.1177/0957154X07080660 The psychiatrist Auguste Forel and his attitude to eugenics BERNHARD KUECHENHOFF* University Hospital of Psychiatry, Zürich Until the end of the 20th century Forel (1848–1931) was seen as an important neuroanatomist, a fi ghter against alcoholism, a researcher on ants and the author of Die sexuelle Frage. Forel’s racist and eugenic views have been for- gotten. Without losing sight of his merits, this article focuses on his attitude to eugenics, and will show that eugenic thinking – based on his main principles – permeated his work. Keywords: Auguste Forel; eugenics; psychiatry; racism; Switzerland Introduction Forel’s achievements and activities were highlighted in an exhibition in Zürich in 1986 and in Bern in 1988, each accompanied by a comprehensive catalogue (Meier, 1986, 1988). -

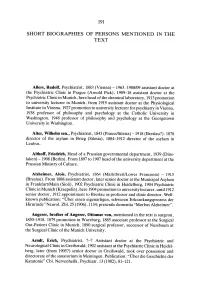

Short Biographies of Persons Mentioned in the Text

191 SHORT BIOGRAPHIES OF PERSONS MENTIONED IN THE TEXT Allers, Rudolf, Psychiatrist, 1883 (Vienna) - 1963. 1908109 assistant doctor at the Psychiatric Clinic in Prague (Arnold Pick), 1909-18 assistant doctor at the Psychiatric Clinic in Munich, here head of the chemical laboratory, 1913 promotion to university lecturer in Munich, from 1919 assistant doctor at the Physiological Institute in Vienna, 1927 promotion to university lecturer for psychiatry in Vienna, 1938 professor of philosophy and psychology at the Catholic University in Washington, 1948 professor of philosophy and psychology at the Georgetown University in Washington. Alter, Wilhelm sen., Psychiatrist, 1843 (PrausS/Silesia) -1918 (Breslau?). 1878 director of the asylum in Brieg (Silesia), 1884-1912 director of the asylum in Leubus. Althoff, Friedrich, Head of a Prussian governmental department, 1939 (Dins laken) -1908 (Berlin). From 1897 to 1907 head of the university department at the Prussian Ministry of Culture. Alzheimer, Alois, Psychiatrist, 1864 (MarktbreitILower Franconia) - 1915 (Breslau). From 1888 assistant doctor, later senior doctor at the Municipal Asylum in FrankfurtlMain (Sioli), 1902 Psychiatric Clinic in Heidelberg, 1904 Psychiatric Clinic in Munich (Kraepelin), here 1904 promotion to university lecturer, until 1912 senior doctor, 1912 appointment to Breslau as professor and clinic director. Well known publication: "Uber einen eigenartigen, schweren Erkrankungsprozess der Hirnrinde" Neurol. Zbl. 25 (1906),1134; presenile dementia "Morbus Alzheimer". Angerer, -

Customized Book List Medicine

ABCD springer.com Springer Customized Book List Medicine FRANKFURT BOOKFAIR 2007 springer.com/booksellers Medicine 1 Forensic Pathology Reviews Vol 6 Novel Trends in Brain Science This series, sponsored by the European Association of Neurosurgical Societies, has already become a Fields of interest Fields of interest classic. In general, one volume is published per year. Pathology Neurosciences; Neuroradiology; Imaging / Radiolo- The advances section presents fields of neurosurgery gy; Neurology and related areas in which important recent progress Type of publication has been made. The technical standards section fea- Contributed volume Type of publication tures detailed descriptions of standard procedures Monograph to assist young neurosurgeons in their post-gradu- Due October 2009 ate training. The contributions are written by experi- Due October 2007 enced clinicians and are reviewed by all members of the editorial board. 2009. 250 p. (Forensic Pathology Reviews, Vol. 6) Hardcover 2007. Approx. 260 illus. Hardcover Contents 74,95 € P-H Roche, P Mercier, T Sameshima, H- ISBN 978-1-58829-833-1 ISBN 978-4-431-73241-9 D Fournier: Surgical anatomy of the jugu- lar foramen.- G Blaauw, RS Muhlig, JW Vredeveld: Management of brachial plexus injuries.- P Cappabi- anca, LM Cavallo, F Esposito, O de Divitiis, A Messi- na, E de Divitiis: Extended endoscopic endonasal ap- proach to the midline skull base: the evolving role of transsphenoidal surgery.- H Duffau: Brain plasticity and tumors.- M Sindou, Gimbert: Decompression of Chiari Type I malformation.- N Pamir, K Ozduman: Tumor biology and current treatment of skull-base chordomas.- B Krischek: The influence of genetics on [..] Fields of interest Neurosurgery; Neurology; Neuroradiology Target groups Clinicians, residents Type of publication Monograph Due December 2007 2008. -

Evolution of Neurology in the German-Speaking Countries Hansruedi Isler* Hochhaus Zur Schanze, Talstrasse 65, CH-8001, Zurich, Switzerland

l of rna Neu Isler, Int J Neurorehabilitation Eng 2017, 4:2 ou ro J r l e a h a DOI: 10.4172/2376-0281.1000264 n b o i i International t l i t a a n t r i o e t n n I ISSN: 2376-0281 Journal of Neurorehabilitation Commentary Open Access Evolution of Neurology in the German-Speaking Countries Hansruedi Isler* Hochhaus zur Schanze, Talstrasse 65, CH-8001, Zurich, Switzerland Abstract In this region 18th century brain research met with scientist’s prejudice against causal interaction of body and soul. Advances in neurology had to rely on rather mythological ideologies such as Phrenology and Vitalism which revived localizing research from the 17th century origins of neurology. In the early 1800s the last great Vitalist, Johannes Müller, set off an explosion of progress in biology that transformed medicine and neurology into applied biology and replaced Müller’s Vitalism by hardline Mechanism. Later in the 1800s the typical Germanic neuro-psychiatrists developed psychiatry and completed cerebral localization, finally obtaining the divorce of neurology from psychiatry. 17th Century students, following his advances, discovered animal, plant and nerve cells and developed modern electrophysiology, sensory physiology and The team of Thomas Willis (Oxford) created neurology, experimental psychology, an expansion of research only comparable to neuroanatomy, neurophysiology from interdisciplinary research on that of the founders of the Royal Society at Oxford. They also replaced brain organs as tools of the soul [1]. The name and the content of Müller’s Vitalism with strict mechanistic reasoning. neurology came out of neuroanatomy like Athena “from the head of Zeus” [2]. -

The Adaption of German Psychiatric Concepts Around 1900 During the Academic Evolution of Modern Psychiatry in China

UNIVERSITÄTSKLINIKUM HAMBURG-EPPENDORF Zentrum für Psychosoziale Medizin, Institut für Geschichte und Ethik der Medizin Prof. Dr. med. Heinz-Peter Schmiedebach International knowledge transfer: The adaption of German Psychiatric Concepts around 1900 during the Academic Evolution of Modern Psychiatry in China Internationale Wissenstransfer: Die Anpassungsfähigkeit der deutschen psychiatrischen Konzepte um 1900 während der akademischen Entwicklung der modernen Psychiatrie in China Dissertation zur Erlangung des Doktorgrades Dr. rer. biol. hum. / PhD an der Medizinischen Fakultät der Universität Hamburg. vorgelegt von: Wenjing Li He Bei, China Hamburg 2016 (wird von der Medizinischen Fakultät ausgefüllt) Angenommen von der Medizinischen Fakultät der Universität Hamburg am:_ 23.09.2016 ______ Veröffentlicht mit Genehmigung der Medizinischen Fakultät der Universität Hamburg. Prüfungsausschuss, der/die Vorsitzende:__Prof. Dr. H.-P. Schmiedebach_ Prüfungsausschuss, zweite/r Gutachter/in:_Prof. Dr. D. Naber__________ Contents Abstract ......................................................................................................... 1 Abstrakt ......................................................................................................... 3 1. Introduction ................................................................................................ 5 1.1 Background & status quo ....................................................................... 5 1.2 Issued question & purpose .................................................................... -

Was King Ludwig II of Bavaria Misdiagnosed by Gudden and His Colleagues?

European Archives of Psychiatry and Clinical Neuroscience https://doi.org/10.1007/s00406-020-01161-8 ORIGINAL PAPER Was King Ludwig II of Bavaria misdiagnosed by Gudden and his colleagues? Reinhard Steinberg1 · Peter Falkai1 Received: 14 April 2020 / Accepted: 29 May 2020 © The Author(s) 2020 Abstract In 1886, Bernhard von Gudden and three other expert psychiatrists diagnosed the Bavarian King Ludwig II with “paranoia (madness),” a diagnosis that the Bavarian government used to justify removing Ludwig from power. Although Ludwig was not evaluated in detail by the psychiatrists, in their opinion, sworn eyewitness accounts and general knowledge about Ludwig’s behavior provided sufcient grounds for the diagnosis. Ludwig was a great admirer of the musician, Richard Wagner, and shared some of his ideas of an idealistic society. At frst, he identifed with Wagner’s opera heroes, and he became Wagner’s patron sponsor for life. However, he grew increasingly interested in an absolutist state, envisioning himself as a monarch with a role similar to that of Louis XIV. His multiple building projects, for which he incurred much debt, his conviction that he was descended from the Bourbons through baptism, his increasingly abnormal behavior, and his hallucinations together formed the basis for the psychiatrists’ diagnosis. Although not mentioned in the expert opinion, Ludwig’s homophilic behav- ior—a scandal at the time—was probably also an important reason for his removal from ofce. A review of the psychiatric knowledge and societal philosophy of the time indicates that the psychiatrists were correct with their diagnosis in their time. Keywords Bernhard von Gudden · Ludwig II · Diagnosis · Paranoia (madness) · Expert opinion Introduction worse, was psychiatry, acting on behalf of the government, responsible for the King’s death? [1–3]. -

Neurosciences in Germany Can

EDITORIAL Neurosciences in Germany Can. J. Neurol. Sci. 1999; 26: 75-76 The article on Neurosciences in the Third Reich: from Ivory Asylum in Frankfurt am Main. In 1901 he moved to Berlin, to Tower to Death Camps1 in this issue reminds us of the prime his- work with Oskar Vogt at the world famous Neurobiology torical example of a scientific establishment shooting itself in the Institute. In 1910 he accepted a post with Robert Gaupp, one of foot: Germany after 1933. Before 1933, Germany was the world Germany’s leading psychiatrists in the Department of Psychiatry epicenter of scientific medicine. After 1933, with Hitler’s acces- at Tübingen. And in 1918 Brodmann became head of the topo- sion to power and the implementation of his antisemitic racial graphic-histologic division of Emil Kraepelin’s recently-founded policies, Germany’s scientific preeminence self-destructed. The German Psychiatry Research Institute in Munich, which would Jewish physicians and scientists who had done so much to give later become the premier neuroscientific institute of the world. German medicine its luster were driven from their posts, forced Had Brodmann not died prematurely of sepsis in August of that into exile, and gassed in concentration camps. At the time in year, he would have had as colleagues at the DFA (as it was 1938 that Nazi Germany invaded Austria, annexing that little known by its German initials Ð today the Max Planck Institute for country to the Third Reich, 65 percent of all physicians in Vienna Psychiatry) such figures as Franz Nissl, whose name is familiar were Jewish. -

Dynastic, Social, Psychological and Psychiatric Aspects of the Bavarian Royal Drama of 1886

ISSN 1712-8056[Print] Canadian Social Science ISSN 1923-6697[Online] Vol. 11, No. 6, 2015, pp. 1-22 www.cscanada.net DOI:10.3968/7086 www.cscanada.org Dynastic, Social, Psychological and Psychiatric Aspects of the Bavarian Royal Drama of 1886 Heinz Häfner[a],* [a]Schizophrenia Research Group, Central Institute of Mental Health, works of the composer Richard Wagner. His devotion Medical Faculty Mannheim / University of Heidelberg and Heidelberg to art, music, literature and radical pacifism cost him Academy of Sciences and Humanities, Germany. the sympathy of many of his people. Nevertheless, *Corresponding author. he accomplished his administrative duties with great Received 18 March 2015; accepted 10 May 2015 consistency and accuracy until his final days. He was Published online 26 June 2015 toppled mainly because of his increasing debt at the expense of his royal family. Abstract Key words: Late European monarchism; The In the royal drama of 1886 King Ludwig II of Bavaria Wittelsbach dynasty; Ludwig II of Bavaria; Dethronement drowned himself, after drowning Prof. von Gudden, who of a king; Death of a king; The 1886 Bavarian royal had tried to hold him back from suicide. The psychiatrist drama; Richard Wagner; Misuse of psychiatry had laid the foundation for the king’s dethronement, legal incapacitation and psychiatric internment with Häfner, H. (2015). Dynastic, Social, Psychological and the incorrect psychiatric assessment he had been Psychiatric Aspects of the Bavarian Royal Drama of 1886. Canadian Social Science, 11(6), 1-22. Available from: commissioned to deliver. The scandalon was the misuse http://www.cscanada.net/index.php/css/article/view/7086 of psychiatry for the purposes of powerful princes.