Vol. 71, No. 2: Full Issue

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

1 Mcculloch, Hugh. Men and Measures of Half a Century. New York

McCulloch, Hugh. Men and Measures of Half a Century. New York: Charles Scribner’s Sons, 1888. CHAPTER I. Growth of England and the United States — Bill for Railroad from Boston to Salem — Jeremiah Mason — Ichabod Bartlett — Stage-coaching — Boston in 1883 — Its Commercial Character^ — ^Massachusetts — Her High Character — Change in Character of New England Population — Boston — Southern Prejudices against New England — Bishop Spaulding's Anecdote 1 CHAPTER II. Changes in New England Theology — The Westminster Catechism — Dr. Channing's Sermon at the Ordination of Mr. Sparks — Division of the Churches— The Unitarians — The Calvinists— Dr. Beecher tried for Heresy — Thomas Pessenden— His Question to a Dying Christian — Plenary Inspiration 10 CHAPTER III, Boston— Its Lawyers — Daniel Webster — His Varied Talents — His Debate with Hayne — Mr. Calhoun — Sectional Feeling — Race between a Northern and Southern Horse — Mr. Webster before a Jury — Franklin Dexter — Benjamin Curtis — W. M. Evarts — William Groesbeck — Rufus Choate — Richard Fletcher — Mr. Choate and Mr. Clay— Mr. Burlingame and Mr. Brooks — Theodore Lyman — Harrison Gray Otis — Josiah Quincy — Edward Everett — Caleb Cushing — Henry W. Longfellow — Oliver W. Holmes — Interesting Incident 16. CHAPTER IV. The Boston Clergy : Channing, Gannett, Parker, Lowell, Ware, Pierpont, Palfrey, Blagden, Edward Beecher, Frothingham, Emerson, Ripley, Walker — Outside of Boston : Upham, Whitman and Nichols, Father Taylor, the Sailor Preacher— James Freeman Clarke — Edward Everett Hale — M. J. Savage — Decline of Unitarianism — The Catholic Church — Progress of Liberal Thought — Position of the Churches in Regard to Slavery — The Slave Question 37 CHAPTER V. Departure from New England — William Emerson — New York — Philadelphia — Baltimore — Wheeling — The Ohio River — Thomas F, Marshall—Emancipation—Feeling in Favor of it checked by the Profits of Slavery — John Bright and the Opium Trade — Mr. -

Conrad Baker Papers, 1858-1902

Indiana Historical Society - Manuscripts and Archives Department CONRAD BAKER PAPERS, 1858-1902 Collections # M 0008 OM 0003 BV 3222-3252 F 0034-0047; 0259-0263 Table of Contents Collection Information Historical Sketch Scope and Content Note Box and Folder Listing Cataloging Information Processed by Paul Brockman 22 June 1998 COLLECTION INFORMATION VOLUME OF 12 manuscript boxes, 30 bound volumes, 18 microfilm reels, 1 COLLECTION: oversize folder COLLECTION DATES: 1858-1902 PROVENANCE: Robert C. Tucker, Jr., Indianapolis, IN, 1963; W. J. Holiday, Sr., 7 October 1966 RESTRICTIONS: Use microfilm copies of letter books in place of originals. REPRODUCTION Permission to reproduce or publish material in this collection RIGHTS: must be obtained from the Indiana Historical Society. ALTERNATE Letter books are on microfilm FORMATS: RELATED HOLDINGS: Arthur G. Mitten Collection (M 0211) ACCESSION NUMBER: 1963.0015, 1966.1007 NOTES: HISTORICAL SKETCH Conrad Baker (1817-1885) was born in Franklin County, Pennsylvania. After attending Pennsylvania College in Gettysburg he studied law in the firm of Stevens and Smyser, under Thaddeus Stevens. In 1841, he moved to Evansville, Vanderburgh County, and started a law practice. During the Civil War, Baker served for three years as a colonel in the 1st Indiana Cavalry (28th Regiment). In 1863, he was assigned to Indianapolis where he became Assistant Provost Marshall General for the state of Indiana. Baker's political career prior to the war included on term as a state representative (1845-1846) and eighteen months as judge for the Court of Common Pleas. In 1865, Baker was nominated to run as lieutenant governor with Oliver P. -

Spring 2006 | Volume 24 Number 1 Volume Volume 24 Number 1 from the Dean Duke Law School

Duke Law Magazine LAW DUKE Duke University Law School NON-PROFIT ORG. Box 90389 U.S. POSTAGE Durham, NC 27708-0389 PAID MAGAZINE Spring 2006 MAGAZINE Spring DURHAM, NC PERMIT NO. 60 Address service requested DUKE L AW MAGAZINE Spring 2006 | Volume 24 Number 1 Volume 24 Number 1 From the Dean Duke Law School Dear Alumni and Friends, As this issue went to press, Duke This issue of Duke Law Magazine focuses Provost Peter Lange announced Spring 2006 on one of the most exciting developments at Katharine T. Bartlett’s decision to step the Law School in recent years—the explo- sion in legal clinics. Ten years ago, Duke’s down as dean of Duke Law School, Selected events only “in-house” legal clinic was the AIDS effective June 30, 2007, at which Legal Assistance Project. This clinic has point she plans to return full-time to become a well established legal resource in the faculty. the community for individuals with HIV and Lange described Bartlett as “a AIDs, and a national model. Since then the JANUARY FEBRUARY MARCH superb dean.” Children’s Education Law Clinic has become a prominent community advocacy service “Her quiet leadership has led to 19 10 3-4 for children with special needs who are seek- an extraordinary expansion of the Law Fifth Annual Rabbi ESQ.: Fourth Annual Seventh Annual ing appropriate educational services. The One way in which we hope to step up our School faculty built on recruitments of Seymour Siegel Business Law Conference of the Community Enterprise Clinic, now in its fourth contacts with alumni is with our new, high- the highest quality and the establish- Lecture in Symposium Program in year, handles complex transactional work end additional CLE programs. -

A Historical Sketch of Johnson County Indiana

Maurer School of Law: Indiana University Digital Repository @ Maurer Law Articles by Maurer Faculty Faculty Scholarship 1881 A Historical Sketch of Johnson County Indiana David Demaree Banta Follow this and additional works at: https://www.repository.law.indiana.edu/facpub Part of the United States History Commons Recommended Citation Banta, David Demaree, "A Historical Sketch of Johnson County Indiana" (1881). Articles by Maurer Faculty. 1078. https://www.repository.law.indiana.edu/facpub/1078 This Brochure is brought to you for free and open access by the Faculty Scholarship at Digital Repository @ Maurer Law. It has been accepted for inclusion in Articles by Maurer Faculty by an authorized administrator of Digital Repository @ Maurer Law. For more information, please contact [email protected]. NYPL RESEARCH LIBRARIES I 3 3433 08181593 2 IVO (ToMSo/VCo.) A HISTORICAL SKETCH OF u w INDIANA. BY D. D. BANTA "This is the place, this is the time. Let mc review the scene, And summon from the shadowy past The forms that once have been." CHICAGO: J. H. BEZELS & CO. 1881. ^00389 Til'- R Entered according to Act of Congress, in the year 1881, by D. D. BANTA, in (he office of the Librarian of Congress, at Washington, D. C. LNTRODUOTOIiY. Every reader of this historical sketch, will, doubtless, think that it ought to have been better than it is. Well, I think so, too if one he can write a let him ; but, any imagines better, try it. Then he will begin to learn in what a chaos everything is that rests in memory, and how eluding important facts are. -

Rytilahti Defense Dissertation

Taking the Moral Ground: Protestants, Feminists, and Gay Equality in North Carolina, 1970-1980 by Stephanie Rytilahti Department of History Duke University Date:_______________________ Approved: ___________________________ Adriane Lentz-Smith, Supervisor ___________________________ Jacquelyn Dowd Hall ___________________________ Pete Sigal ___________________________ Timothy Tyson ___________________________ Nancy MacLean Dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Department of History in the Graduate School of Duke University 2018 ABSTRACT Taking the Moral Ground Protestants, Feminists, and Gay Equality in North Carolina, 1970-1980 by Stephanie Rytilahti Department of History Duke University Date:_______________________ Approved: ___________________________ Adriane Lentz-Smith, Supervisor ___________________________ Jacquelyn Dowd Hall ___________________________ Peter Sigal ___________________________ Timothy Tyson ___________________________ Nancy MacLean Dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Department of History in the Graduate School of Duke University 2018 Copyright by Stephanie Rytilahti 2018 Abstract “Taking the Moral Ground” examines the relationship between Protestantism and the movements for feminist and gay equality in North Carolina during the 1970s and 1980s to answer two central questions: How did a group of white heterosexual clergy, moderate mainliners, and African American ministers in central North Carolina become the spokespersons for feminist and gay liberation in the 1970s and 1980s? What did the theoretical frameworks of organized religion offer that made these types of unlikely alliances possible? To answer these questions “Taking the Moral Ground” begins with an exploration of the religious values that framed the upbringing, activist career, and ministry of Pauli Murray, a native of North Carolina and the first African American woman ordained by the Episcopal Church. -

A Political Manual for 1869

A POLITICAL. ~IANUAL FOR 1869, I~CLUDING A CLASSIFIED SUMMARY OF THE IMPORTANT EXECUTIVE, LEGISLATIVE,JUDICIAL, POLITICO-MILITARY GENERAL FACTS OF THE PERIOD. From July 15, 1868. to July 15, 1869. BY EDWARD McPHERSON, LL.D., CLERK OF TllB ROUS!: OF REPRESENTATIVES OF TU:B U!flTED STATES. WASHINGTON CITY : PHILP & SOLOMONS. 1869. Entered according to Act of Congress, in the year 186?, by EDWAR}) McPIIERSON, In the Clerk's Office of the District Conrt of the United Sto.tes for the District of Columbia. _.......,============================ • 9-ootype<il>J llihOILI, <l WITHEROW, Wa.aLingturi., O. C. PREFACE. This volume contains the same class of facts found in the :Manual for 1866, 1867, and 1868. .The record is continued from the date of the close of the Manual for 1868, to the present time. The votes in Congress during the struggle· which resulted in the passage of the Suffrage or XVth Amendment of the Constitution of the United States, will disclose the contrariety of opinion which prevailed upon this point, and the mode in which an adjustment was reached; while the various votes upon it in the State Legislatures will show the present state of the question of Ratification. The a<Jditional legislation on Reconstruction, with the Executive and l\Iilitary action under it; the conflict on the Tenure-of-Office Act and the Public Credit Act; the votes upon the mode of payment of United States Bonds, Female Suffrage, l\Iinority Representation, Counting the Electoral Votes, &c.; the l\Iessage of the late President, and the Condemnatory Votes -

William Hayden English Family Papers, 1741–1928

Collection # M 0098 OMB 0002 BV 1137–1148, 2571–72, 2574 F 0595p WILLIAM HAYDEN ENGLISH FAMILY PAPERS, 1741–1928 Collection Information Biographical Sketches Scope and Content Note Series Contents Processed by Reprocessed by Betty Alberty, Ruth Leukhardt, Paul Brockman, and Pamela Tranfield 08 January 2003 Manuscript and Visual Collections Department William Henry Smith Memorial Library Indiana Historical Society 450 West Ohio Street Indianapolis, IN 46202-3269 www.indianahistory.org COLLECTION INFORMATION VOLUME OF 103 boxes, 3 oversize boxes, 15 bound volumes, 1 microfilm COLLECTION: reel, 76 boxes of photographs (16 document cases, 12 oversize boxes, 17 boxes cased images, 2 boxes lantern slides, 27 boxes glass negatives, 2 boxes film negatives), 6 boxes of graphics (1 document case, 5 oversize boxes). COLLECTION 1741–1928 DATES: PROVENANCE: Mrs. William E. English Estate, May 1942; Indiana University, July 1944; Forest H. Sweet, Battle Creek, Michigan, August 1937, July 1945, Dec. 1953; University of Chicago Libraries, April 1957; English Foundation, Indianapolis IN, 1958; Mrs. A. G. Parker, Lexington, IN, Sept. 1969; King V. Hostick, Springfield IL, March 1970; Duanne Elbert, Eastern Illinois University, Oct. 1974; Hyman Roth, Evanston IL, Aug. 1975 RESTRICTIONS: Negatives may be viewed by appointment only. Inquire at the Reference Desk. COPYRIGHT: REPRODUCTION Permission to reproduce or publish material in this collection RIGHTS: must be obtained from the Indiana Historical Society. ALTERNATE FORMATS: RELATED English Theatre Records (M 0451) HOLDINGS: ACCESSION 1937.0803; 1942.0512; 1944.0710; 1945.0707; 1953.1226; NUMBERS: 1957.0434; 1958.0015; 1969.0904; 1970.0317; 1974.1018; 1975.0810 NOTES: Originally processed by Charles Latham, 1983 BIOGRAPHICAL SKETCHES William Hayden English, 1822–96 William H. -

Crown Hill's Origin and Development.Pub

CROWN HILL’S ORIGIN AND DEVELOPMENT Beauty of the Cemetery Due to Unselfish Spirit and Wise Management. NATURE’S CHARMS PRESERVED Consistent Course by Which Effects of Serenity, Peace and Seclusion Have Been Maintained. “The cemetery is an open space among the ruins, covered in winter with violets and daisies. It might make one in love with death to think that one should be buried in so sweet a place.” So wrote the English poet Shelley concerning the Protestant cemetery in Rome, in which by a strange coincidence, he himself was finally laid to rest. The same thought would apply in some degree to Crown Hill Cemetery in Indianapolis. Not that it is “an open space among ruins,” like the little cemetery at Rome, for though it is surrounded by all the marks of modern progress. The atmosphere of sacred seclusion that pervades the inclosure seems to say to the waves of worldly activity that surround its borders, “Thus far shalt thou come but no farther.” The living who pass its portals fine themselves at once in an atmosphere entirely distinct from that they left behind, and the dead who find their final resting place amid its quiet borders must feel grateful, if the dead experience human emotions, that their mortal remains have been buried in so sweet a place. Crown Hill cemetery is a product of evolution, and is typical of the growth of Indianapolis through various stages from a frontier settlement to a straggling village, a capital in the woods, a sleepy country town, a prosperous railroad center, a robust community feeling its strength and demanding recognition, to a metropolitan city of national fame. -

The Eastern Edge, Summer 2000" (2000)

Eastern Michigan University DigitalCommons@EMU Alumni News University Archives 2000 The aE stern Edge, Summer 2000 Eastern Michigan University Follow this and additional works at: http://commons.emich.edu/alumni_news Recommended Citation Eastern Michigan University, "The Eastern Edge, Summer 2000" (2000). Alumni News. 270. http://commons.emich.edu/alumni_news/270 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the University Archives at DigitalCommons@EMU. It has been accepted for inclusion in Alumni News by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@EMU. For more information, please contact [email protected]. EASTERN MICHIGAN UN LVERSITY · Office for Alumni Relations· Volume 3, Number 3 Summer 2000 President Clinton Speaks at EMU Graduation by Ron Podell, officeof public iriformation The technology revolution is providing information opportunities in ways previously never imagined. How ever, those same technological advances are also raising serious questions about tlueats to public privacy, said President William Jefferson Clinton during his com mencement address to more than 1,300 Eastern Michi gan University graduates April 30. "Today, as information technology opens new worlds of possibilities, it also challenges privacy in ways we might never have imagined just a few years ago," Clinton said. "For example, the same genetic code that offers hopes for millions can also be used to deny health insurance. The same technology that links distant places can also be used to track our every move on-line." The standing-room-only crowd did tl1e usual neck straining and flashbulb popping as the graduates marched into Eastern Michigan's Convocation Center. But there was an extra electricity in the air, as the crowd buzzed with anticipation for President Clinton's arrival. -

The Fugitive Slave Law, Antislavery and the Emergence of the Republican Party in Indiana

Purdue University Purdue e-Pubs Open Access Dissertations Theses and Dissertations Fall 2013 The uF gitive Slave Law, Antislavery and the Emergence of the Republican Party in Indiana Christopher David Walker Purdue University Follow this and additional works at: https://docs.lib.purdue.edu/open_access_dissertations Part of the United States History Commons Recommended Citation Walker, Christopher David, "The uF gitive Slave Law, Antislavery and the Emergence of the Republican Party in Indiana" (2013). Open Access Dissertations. 17. https://docs.lib.purdue.edu/open_access_dissertations/17 This document has been made available through Purdue e-Pubs, a service of the Purdue University Libraries. Please contact [email protected] for additional information. Graduate School ETD Form 9 (Revised 12/07) PURDUE UNIVERSITY GRADUATE SCHOOL Thesis/Dissertation Acceptance This is to certify that the thesis/dissertation prepared By Christopher David Walker Entitled THE FUGITIVE SLAVE LAW, ANTISLAVERY AND THE EMERGENCE OF THE REPUBLICAN PARTY IN INDIANA Doctor of Philosophy For the degree of Is approved by the final examining committee: Robert E. May Chair Michael A. Morrison John L. Larson Yvonne M. Pitts To the best of my knowledge and as understood by the student in the Research Integrity and Copyright Disclaimer (Graduate School Form 20), this thesis/dissertation adheres to the provisions of Purdue University’s “Policy on Integrity in Research” and the use of copyrighted material. Approved by Major Professor(s): ____________________________________Robert -

Finding Aid from the Manuscript Section of the Indiana State Library

Oliver P. Morton Papers L113, OB5 folder 14, OBC44, V438 1855-1909 7 mss. boxes, 2 os. folders, 1 vol. Rare Books and Manuscripts Division Indiana State Library Reprocessed by: Barbara Hilderbrand, February 2007 Finding aid updated: Laura Eliason, 11/04/2015; Lauren Patton 17/03/2016 Biographical Note: Oliver P. Morton was born August 4, 1823 in Salisbury, Wayne County, Indiana. He was apprenticed to a hatter and worked in that career for four years before attending Wayne County Seminary and Miami University in Oxford, Ohio. Morton Studied law and was admitted to the bar in 1847. He began his law practice in Centerville, Indiana. He was elected judge of the Sixth Judicial Circuit of Indiana in 1852. He ran unsuccessfully for governor of Indiana in 1856 but was elected lieutenant governor under Henry S. Lane in 1860. He became governor in 1861 upon Lane’s election to the U.S. Senate. He served as governor until 1867 when he was elected to the U.S. Senate. While in the Senate Morton served on the Committee on Manufactures, Committee on Agriculture, and the Committee on Privileges and Elections. He was appointed to the Electoral Commission of 1877 to decide contests in various states during the presidential election of 1876. Oliver P. Morton died on November 1, 1877 in Indianapolis and is interred at Crown Hill Cemetery. Source: Biographical Directory of the United States Congress. United States Congress. 24 January 2007 <http://bioguide.congress.gov/scripts/biodisplay.pl?index=M001020> Scope and Content Note: This collection consist primarily of correspondence and papers from Morton’s Senatorial career with an emphasis on the1876 presidential election and Louisiana politics in 1873 and 1874. -

The Ac- Ait Urth Red Om- Ent, Rty- One Son, , N. First Un

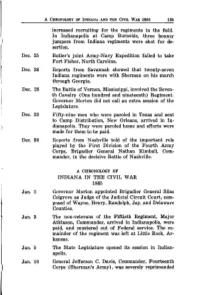

A CF~RONOLOGYOF INDIANA AND THE CIVIL WAR 1865 135 art of the government in the increased recruiting for the regiments in the field. uded and the cases submitted In Indianapolis at Camp Bnmside, three bounty jumpers from Indiana regiments were shot for de- sertion. ndred rebel prisoners arrived .e quartered in Camp Morton. Dec. 25 Butler's joint Army-Navy Expedition failed to take Fort Fisher, North Carolina. nt issued its seventh call for 00,000 men for 1, 2, or 3 years Dec. 26 Reports from Savannah showed that twenty-seven one of the editors of the De- Indiana regiments were with Sherman on his march Eagle, was arrested by the through Georgia. at district for treasonous ac- Dec. 28 The Battle of Vernon, Mississippi, involved the Seven- in a military prison to await th Cavalry (One hundred and nineteenth) Regiment. Governor Morton did not call an extra session of the 'orty-third Regiment, John F. Legislature. e hundred and forty-fourth e, Commander; One hundred Dec. 29 Fifty-nine men who were paroled in Texas and sent ent, John A. Platter, Com- to Camp Distribution, New Orleans, arrived in In- and forty-seventh Regiment, dianapolis. They were paroled home and efforts were ~der;One hundred and forty- made for them to be paid. s Burgess, Commander; One Dec. 30 Reports from Nashville told of the important role th Regiment, R. N. Hudson, played by the First Division of the Fourth Army red and fiftieth Regiment, N. Corps, Brigadier General Nathan Kimball, Com- ; One hundred and fifty-first mander, in the decisive Battle of Nashville.