Anselm Heinrich

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

![Theater Souvenir Programs Guide [1881-1979]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/6681/theater-souvenir-programs-guide-1881-1979-256681.webp)

Theater Souvenir Programs Guide [1881-1979]

Theater Souvenir Programs Guide [1881-1979] RBC PN2037 .T54 1881 Choose which boxes you want to see, go to SearchWorks record, and page boxes electronically. BOX 1 1: An Illustrated Record by "The Sphere" of the Gilbert & Sullivan Operas 1939 (1939). Note: Operas: The Mikado; The Goldoliers; Iolanthe; Trial by Jury; The Pirates of Penzance; The Yeomen of the Guard; Patience; Princess Ida; Ruddigore; H.M.S. Pinafore; The Grand Duke; Utopia, Limited; The Sorcerer. 2: Glyndebourne Festival Opera (1960). Note: 26th Anniversary of the Glyndebourne Festival, operas: I Puritani; Falstaff; Der Rosenkavalier; Don Giovanni; La Cenerentola; Die Zauberflöte. 3: Parts I Have Played: Mr. Martin Harvey (1881-1909). Note: 30 Photographs and A Biographical Sketch. 4: Souvenir of The Christian King (Or Alfred of "Engle-Land"), by Wilson Barrett. Note: Photographs by W. & D. Downey. 5: Adelphi Theatre : Adelphi Theatre Souvenir of the 200th Performance of "Tina" (1916). 6: Comedy Theatre : Souvenir of "Sunday" (1904), by Thomas Raceward. 7: Daly's Theatre : The Lady of the Rose: Souvenir of Anniversary Perforamnce Feb. 21, 1923 (1923), by Frederick Lonsdale. Note: Musical theater. 8: Drury Lane Theatre : The Pageant of Drury Lane Theatre (1918), by Louis N. Parker. Note: In celebration of the 21 years of management by Arthur Collins. 9: Duke of York's Theatre : Souvenir of the 200th Performance of "The Admirable Crichton" (1902), by J.M. Barrie. Note: Oil paintings by Chas. A. Buchel, produced under the management of Charles Frohman. 10: Gaiety Theatre : The Orchid (1904), by James T. Tanner. Note: Managing Director, Mr. George Edwardes, musical comedy. -

Ancient Rome on Wilson Barrett's

“A LIVING HISTORY”: ANCIENT ROME ON WILSON BARRETT’S STAGE by Shoshana Hereld A THESIS SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF ARTS in THE FACULTY OF GRADUATE AND POSTDOCTORAL STUDIES (Theatre) THE UNIVERSITY OF BRITISH COLUMBIA (Vancouver) August 2017 © Shoshana Hereld, 2017 Abstract The toga dramas of late nineteenth-century British actor-manager Wilson Barrett provide important evidence on the relationship between the Classics and Victorian theater. In his depictions of ancient Rome, Barrett married the popularity of melodrama with the passion for classical antiquity, reflecting changes in the Victorian social world at the end of the nineteenth century: the increasing prominence of melodrama and the blurring of artistic genres; the increasing accessibility of classical knowledge; and obsessions with historicity. Drawing on scripts, contemporary reviews, and photographs, I investigate the ways in which Barrett’s work navigates the existing social scene in both theater and society at large. By exploring the splendor of Victorian melodrama, the British tastes for the Classics, and the relationship between authenticity and theatricality, this thesis uses Wilson Barrett’s work to demonstrate important features of both Victorian theater and society at large at the end of the nineteenth century. ii Lay Summary The toga dramas of late nineteenth-century British actor-manager Wilson Barrett provide important evidence on the relationship between the Classics and Victorian theater. Barrett is relatively unstudied, as compared to his contemporaries, such as Sir Henry Irving. Barrett’s depictions of ancient Rome, however, reflect both Victorian attitudes towards classical history and changes in British social structure. -

3. Terence Rattigan- First Success and After

DIPLOMARBEIT Titel der Diplomarbeit „In and out of the limelight- Terence Rattigan revisited“ Verfasserin Covi Corinna angestrebter akademischer Grad Magistra der Philosophie (Mag.phil.) Wien, 30. Jänner 2013 Studienkennzahl lt. Studienblatt: A 343 Studienrichtung lt. Studienblatt: 343 Diplomstudium Anglistik und Amerikanistik UniStG Betreuer: Ao. Univ.-Prof. Dr. Rudolf Weiss Table of contents 1. Introduction……………………………………………………....p.4 2. The History of the Well-Made Play…………………………......p.5 A) French Precursors.....................................................................p.6 B) The British Well-Made Play...................................................p.10 a) Tom Robertson and the 1870s...........................................................p.10 b) The “Renaissance of British Drama”...............................................p.11 i. Arthur Wing Pinero (1855-1934) and Henry Arthur Jones (1851- 1929)- The precursors of the “New Drama”..............................p.12 ii. Oscar Wilde (1854-1900)..............................................................p.15 c) 1900- 1930 “The Triumph of the New Drama”...............................p.17 i. Harley Granville-Barker (1877-1946)………………................p.18 ii. William Somerset Maugham (1874-1965)..................................p.18 iii. Noel Coward (1899-1973)............................................................p.20 3. Terence Rattigan- first success and after...................................p.21 A) French Without Tears (1936)...................................................p.22 -

Broadside Read- a Brief Chronology of Major Events in Trous Failure

NEWSLETTER OF THE THEATRE LIBRARY ASSOCIATION Volume 17, Number 1/Volume 17, Number 2 SPECIAL DOUBLE ISSUE Summer/Fa111989 EXHIBITION SURVEYS MANHATTAN'S EARLY THEATRE HISTORY L An exhibition spotlighting three early New York theatres was on view in the Main I Gallery of The New York Public Library at Lincoln Center from February 13, 1990 through March 31, 1990. Focusing on the Park Theatre on Park Row, Niblo's Garden on Broadway and Prince Street, and Wal- lack's, later called the Star, on Broadway and 13th Street, the exhibition attempted to show, through the use of maps, photo- graphic blowups, programs and posters, the richness of the developing New York theatre scene as it moved northward from lower Manhattan. The Park Theatre has been called "the first important theatre in the United States." It opened on January 29, 1798, across from the Commons (the Commons is now City Hall Park-City Hall was built in 1811). The opening production, As You Like It, was presented with some of the fin- est scenery ever seen. The theatre itself, which could accommodate almost 2,000, was most favorably reviewed. It was one of the most substantial buildings erected in the city to that date- the size of the stage was a source of amazement to both cast and audience. In the early nineteenth century, to increase ticket sales, manager Stephen Price introduced the "star sys- tem" (the importation of famous English stars). This kept attendance high but to some extent discouraged the growth of in- digenous talent. In its later days the Park was home to a fine company, which, in addition to performing the classics, pre- sented the work of the emerging American playwrights. -

ISSUE 3 Autumn 2012

StMartin-MOORINGS_Layout 1 01/11/2012 14:05 Page 1 ISSUE 3 Autumn 2012 Autumn Christmas Set Lunch highlights at The Moorings Hotel n Our homemadeFrom soup of the day theSmoked Tuesdeay haddock fishcake with 4thwhite wine December mand Homemade Christmas Grilled goats cheese with herb veloute pudding with brandy sauce cranberry and walnut salad Escalope of turkey breast with smoked bacon, Vanilla crème brulee Potted crab and prawns served chestnut and sage jus Brown sugar mernigue with granary toast Braised steak in red wine sauce with with whipped cream and Terrine of local game with horseradish mash spiced fruits mulled wine pear chutney Crispy confit of duck with roast root Chocolate and baileys mousse Rillette of salmon wrapped in vegetables and thyme jus with cappuccino cream oak smoked Scottish salmon Roast vegetable and chestnut tart glazed Port creamed stilton with with brie walnut bread Coffee and homemade petit fours 1.75 In this issue: St Martin’s P3 From the Connétable £ are available 2 course 12.50 or 3 course 14.75 Gift Vouchers P4 Steve Luce: never say never for overnight offers and Battle Float Available to Monday to Saturday booking See P5 Parish News: from the Connétable £ £ restaurant reservations, ideal page 11 is advisable Tel: 853633 Christmas presents.... P9 Club News: Jumelage and Battle of Flowers success P22 Farming News: Christmas trees grown in St Martin P24 Sports News: St Martin’s FC looks to the future P29 Church News: over 100 years of service The Moorings Hotel & Restaurant P32 Parish Office www.themooringshotel.com P34 Dates for your Diary The Moorings Hotel and Restaurant Gorey Pier St Martin Jersey JE3 6EW Feature Articles listed on page 3 The answer’s easy.. -

Part I ∗ 1895–1946

Cambridge University Press 978-0-521-65132-5 - The Cambridge History of British Theatre: Volume 3: Since 1895 Edited by Baz Kershaw Excerpt More information part i ∗ 1895–1946 © in this web service Cambridge University Press www.cambridge.org Cambridge University Press 978-0-521-65132-5 - The Cambridge History of British Theatre: Volume 3: Since 1895 Edited by Baz Kershaw Excerpt More information © in this web service Cambridge University Press www.cambridge.org Cambridge University Press 978-0-521-65132-5 - The Cambridge History of British Theatre: Volume 3: Since 1895 Edited by Baz Kershaw Excerpt More information 1 British theatre, 1895–1946: art, entertainment, audiences – an introduction dennis kennedy In 1895 three major figures in the history of British theatre came centre stage in revealing ways. Henry Irving, master of theatrical illusion and the most famous performer of the age, knelt before Queen Victoria and rose as the first actor in history to be knighted. Oscar Wilde, that Dubliner brilliant in his plays and impudent in society,had two productions running simultaneously in London: An Ideal Husband and The Importance of Being Earnest.G.B.Shaw, virtually unknown as a playwright, began a three-year mission of modernity and social- ism as theatre critic for the Saturday Review. Shaw complained frequently that Irving, whom he greatly admired, wasted his talents on weak and insignificant work, and he was disturbed to find himself laughing mechanically at Wilde’s masterpiece. Shortly after The Importance of Being Earnest’s brilliant opening, Wilde was in grave trouble with the law over his homosexuality.Just as his play marks the high point of Victorian comedy,so Wilde’s trial signals a turn in the history of Victorian righteousness. -

Noted English Actresses in American Vaudeville, 1904-1916

“The Golden Calf”: Noted English Actresses in American Vaudeville, 1904-1916 Leigh Woods Vaudeville began as a popular American form, with roots in barrooms before audiences of generally Z unsophisticated tastes. By the time it reached its Jessie Millward was known in her native zenith as a popular form during the first two decades country as a heroine in melodramas. Wholesome of this century, however, it showed a pronounced and fresh-faced, she had entered professional acting taste for foreign attractions rather than for the native in 1881, and joined Sir Henry Irving’s prestigious ones that earlier had anchored its broad accessibility. Lyceum company in London as an ingenue the In these years just after the turn of the century, following year. Her first tour of the United States notable foreign actors from the English-speaking came in 1885, and later that year she acted at what theatre made their ways into vaudeville, aligning would become the citadel of London melodrama, the form, though usually in fleeting and superficial at the Adelphi with William Terriss (Millward, ways, with the glamor and prestige the contempor- Myself 315-16). Her name became indissolubly ary stage enjoyed. This pattern bespeaks the linked with Terriss’ as her leading man through willingness to borrow and the permutable profile their appearances in a series of popular melodramas; that have characterized many forms of popular and this link was forged even more firmly when, entertainment. in 1897, Terriss died a real death in her arms Maurice Barrymore (father to Ethel, Lionel and backstage at the Adelphi, following his stabbing John) foreshadowed what would become the wave by a crazed fan in one of the earliest instances of of the future when, in 1897, he became the first violence which can attend modern celebrity (Rowel1 important actor to enter vaudeville. -

The Work of the Little Theatres

TABLE OF CONTENTS PART THREE PAGE Dramatic Contests.144 I. Play Tournaments.144 1. Little Theatre Groups .... 149 Conditions Eavoring the Rise of Tournaments.150 How Expenses Are Met . -153 Qualifications of Competing Groups 156 Arranging the Tournament Pro¬ gram 157 Setting the Tournament Stage 160 Persons Who J udge . 163 Methods of Judging . 164 The Prizes . 167 Social Features . 170 2. College Dramatic Societies 172 3. High School Clubs and Classes 174 Florida University Extension Con¬ tests .... 175 Southern College, Lakeland, Florida 178 Northeast Missouri State Teachers College.179 New York University . .179 Williams School, Ithaca, New York 179 University of North Dakota . .180 Pawtucket High School . .180 4. Miscellaneous Non-Dramatic Asso¬ ciations .181 New York Community Dramatics Contests.181 New Jersey Federation of Women’s Clubs.185 Dramatic Work Suitable for Chil¬ dren .187 4 TABLE OF CONTENTS PAGE II. Play-Writing Contests . 188 1. Little Theatre Groups . 189 2. Universities and Colleges . I9I 3. Miscellaneous Groups . • 194 PART FOUR Selected Bibliography for Amateur Workers IN THE Drama.196 General.196 Production.197 Stagecraft: Settings, Lighting, and so forth . 199 Costuming.201 Make-up.203 Acting.204 Playwriting.205 Puppetry and Pantomime.205 School Dramatics. 207 Religious Dramatics.208 Addresses OF Publishers.210 Index OF Authors.214 5 LIST OF TABLES PAGE 1. Distribution of 789 Little Theatre Groups Listed in the Billboard of the Drama Magazine from October, 1925 through May, 1929, by Type of Organization . 22 2. Distribution by States of 1,000 Little Theatre Groups Listed in the Billboard from October, 1925 through June, 1931.25 3. -

The Contributions of James F. Neill to the Development of the Modern Ameri Can Theatrical Stock Company

This dissertation has been 65—1234 microfilmed exactly as received ZUCCHERO, William Henry, 1930- THE CONTRIBUTIONS OF JAMES F. NEILL TO THE DEVELOPMENT OF THE MODERN AMERI CAN THEATRICAL STOCK COMPANY. The Ohio State University, Ph.D., 1964 Speech—Theater University Microfilms, Inc., Ann Arbor, Michigan Copyright by William Henry Zucchero 1965 THE CONTRIBUTIONS OF JAMES F. NEILL TO THE DEVELOPMENT OF THE MODERN AMERICAN THEATRICAL STOCK COMPANY DISSERTATION Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By William Henry Zucchero, B.S., M.A. * * * * * $ The Ohio State University 1964 Approved by PLEASE NOTE: Plates are not original copy. Some are blurred and indistinct. Filmed as received. UNIVERSITY MICROFILMS, INC. PREFACE Appreciation is extended to the individuals, named below, for the aid each has given in the research, prepara tion, and execution of this study. The gathering of pertinent information on James F. Neill, his family, and his early life, was made possible through the efforts of Mrs. Eugene A. Stanley of the Georgia Historical Society, Mr. C. Robert Jones (Director, the Little Theatre of Savannah, Inc.), Miss Margaret Godley of the Savannah Public Library, Mr. Frank Rossiter (columnist, The Savannah Morning News). Mrs. Gae Decker (Savannah Chamber of Commerce), Mr. W. M. Crane (University of Georgia Alumni Association), Mr. Don Williams (member of Sigma Alpha Epsilon— Neill’s college fraternity), and Mr. Alfred Kent Mordecai of Savannah, Georgia. For basic research on the operation of the Neill company, and information on stock companies, in general, aid was provided by Mrs. -

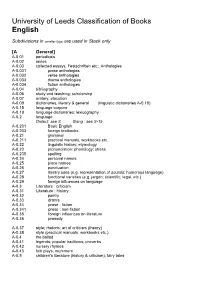

University of Leeds Classification of Books English

University of Leeds Classification of Books English Subdivisions in smaller type are used in Stack only [A General] A-0.01 periodicals A-0.02 series A-0.03 collected essays, Festschriften etc.; Anthologies A-0.031 prose anthologies A-0.032 verse anthologies A-0.033 drama anthologies A-0.034 fiction anthologies A-0.04 bibliography A-0.06 study and teaching; scholarship A-0.07 oratory; elocution A-0.09 dictionaries, literary & general (linguistic dictionaries A-0.19) A-0.15 language corpora A-0.19 language dictionaries; lexicography A-0.2 language Dialect: see S Slang : see S-15 A-0.201 Basic English A-0.203 foreign textbooks A-0.21 grammar A-0.211 practical manuals, workbooks etc. A-0.22 linguistic history; etymology A-0.23 pronunciation; phonology; stress A-0.235 spelling A-0.24 personal names A-0.25 place names A-0.26 punctuation A-0.27 literary uses (e.g. representation of sounds; humorous language) A-0.28 functional varieties (e.g. jargon; scientific, legal, etc.) A-0.29 foreign influences on language A-0.3 Literature : criticism A-0.31 Literature : history A-0.32 poetry A-0.33 drama A-0.34 prose : fiction A-0.341 prose : non-fiction A-0.35 foreign influences on literature A-0.36 prosody A-0.37 style; rhetoric; art of criticism (theory) A-0.38 style (practical manuals, workbooks etc.) A-0.4 the ballad A-0.41 legends; popular traditions; proverbs A-0.42 nursery rhymes A-0.43 folk plays; mummers A-0.5 children’s literature (history & criticism); fairy tales [B Old English] B-0.02 series B-0.03 anthologies of prose and verse Prose anthologies -

The Theatre Royal Bristol

.. THE THEATRE ROYAL BRISTOL DECLINE AND REBIRTH 1834-1943 KATHLEEN BARKER, M.A. ISSUED BY 11HE BRISTOL BRANCH OF THE IDSTORICAL ASSOCIATION THE UNIVERSITY, BRISTOL Price Two Shillings and Six Pence Prmted by F. Bailey & Son I.Jtd., Du.rsley, Glos. 1966 � J- l (-{ :J) BRISTOL BRANCH OF THE HISTORICAL ASSOCIATION THE THEATRE ROYAL, BRISTOL LOCAL HISTORY PAMPHLETS DECLINE AND REBIRTH (1834 - 1943) Hon. General Editor: PATRICK McGRATH Assistant General Editor: PETER HARRIS by Kathleen Barker, M.A. The Theatre Royal, Bristol: Decline and Rebirth (1834-1943) is The Victorian age is not one on which the theatre historian the fourteenth in a series of pamphlets issued by the Bristol Branch looks back with any great pleasure, although it is one of consider of the Historical Association through its standing Committee able interest. The London theatrical scene was initially dominated on Local History (Hon. Secretary. Miss Ilfra Pidgeon). In an earlier by the two great Patent theatres of Covent Garden and Drury pamphlet. first published in 1961, Miss Barker dealt with the Lane, both. rebuilt on a scale too large to suit "legitimate" drama. history of the Theatre Royal during the first seventy years of its Around them had sprung up a myriad Minor Theatres, legally existence. Her work attracted great interest. and a second edition able only to offer spectacle and burletta: a character in which they was published in 1963. She now brings up to modem times the were too well established for the passing of the Act for Regulating largely untold and fascinating story of the oldest provincial theatre the Theatres, which ended the monopoly of the Patent theatres in with a continuous working history. -

Performing Illness in the Late-Nineteenth-Century Theatre

STAGES OF SUFFERING: PERFORMING ILLNESS IN THE LATE-NINETEENTH-CENTURY THEATRE by Meredith Ann Conti Bachelor of Fine Arts, Denison University, 2001 Master of Arts, University of Pittsburgh, 2007 Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of The School of Arts and Sciences in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy University of Pittsburgh 2011 UNIVERSITY OF PITTSBURGH SCHOOL OF ARTS AND SCIENCES This dissertation was presented by Meredith Ann Conti It was defended on April 11, 2011 and approved by Attilio Favorini, PhD, Professor, Theatre Arts Kathleen George, PhD, Professor, Theatre Arts Michael Chemers, PhD, Associate Professor, Carnegie Mellon University, Drama Dissertation Advisor: Bruce McConachie, PhD, Professor, Theatre Arts ii Copyright © by Meredith Ann Conti 2011 iii STAGES OF SUFFERING: PERFORMING ILLNESS IN THE LATE-NINETEENTH-CENTURY THEATRE Meredith Ann Conti, PhD University of Pittsburgh, 2011 Few life occurrences shaped individual and collective identities within Victorian society as critically as suffering (or witnessing a loved one suffering) from illness. Boasting both a material reality of pathologies, morbidities, and symptoms and a metaphorical life of stigmas, icons, and sentiments, the cultural construct of illness was an indisputable staple on the late-nineteenth- century stage. This dissertation analyzes popular performances of illness (both somatic and psychological) to determine how such embodiments confirmed or counteracted salient medical, cultural, and individualized expressions of illness. I also locate within general nineteenth-century acting practices an embodied lexicon of performed illness (comprised of readily identifiable physical and vocal signs) that traversed generic divides and aesthetic movements. Performances of contagious disease are evaluated using over sixty years of consumptive Camilles; William Gillette’s embodiment of the cocaine-injecting Sherlock Holmes and Richard Mansfield’s fiendishly grotesque transformations in the double role of Dr.