Building the Ark Zoos May Have to Choose Between Keeping the Animals We Most Want to See and Saving the Ones We May Never See Again

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Dietary Behavior of the Mangrove Monitor Lizard (Varanus Indicus)

DIETARY BEHAVIOR OF THE MANGROVE MONITOR LIZARD (VARANUS INDICUS) ON COCOS ISLAND, GUAM, AND STRATEGIES FOR VARANUS INDICUS ERADICATION A THESIS SUBMITTED TO THE GRADUATE DIVISION OF THE UNIVERSITY OF HAWAI’I AT HILO IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF SCIENCE IN TROPICAL CONSERVATION BIOLOGY AND ENVIRONMENTAL SCIENCE MAY 2016 By Seamus P. Ehrhard Thesis Committee: William Mautz, Chairperson Donald Price Patrick Hart Acknowledgements I would like to thank Guam’s Department of Agriculture, the Division of Aquatic and Wildlife Resources, and wildlife biologist, Diane Vice, for financial assistance, research materials, and for offering me additional staffing, which greatly aided my fieldwork on Guam. Additionally, I would like to thank Dr. William Mautz for his consistent help and effort, which exceeded all expectations of an advisor, and without which I surely would have not completed my research or been inspired to follow my passion of herpetology to the near ends of the earth. 2 Abstract The mangrove monitor lizard (Varanus indicus), a large invasive predator, can be found on all areas of the 38.6 ha Cocos Island at an estimated density, in October 2011, of 6 V. Indicus per hectare on the island. Plans for the release of the endangered Guam rail (Gallirallus owstoni) on Cocos Island required the culling of V. Indicus, because the lizards are known to consume birds and bird eggs. Cocos Island has 7 different habitats; resort/horticulture, Casuarina forest, mixed strand forest, Pemphis scrub, Scaevola scrub, sand/open area, and wetlands. I removed as many V. Indicus as possible from the three principal habitats; Casuarina forest, mixed scrub forest, and a garbage dump (resort/horticulture) using six different trapping methods. -

Vision Document for the EAZA Biobank Towards EAZA-Wide DNA Biobanking for Population Management

Vision document for the EAZA Biobank Towards EAZA-wide DNA biobanking for population management Vision The EAZA membership will establish dedicated biobanking facilities for the European zoo community. This biobank aims to be a primary resource for genetically supporting population management and conservation research. Introduction The success of EAZA ex situ programmes relies on intensive demographic and genetic management of animal populations. Currently, the majority of genetic management in zoos is individual, pedigree- based management. This often causes problems because for many populations pedigree records are incomplete and relatedness of founders is built on assumptions. Furthermore, many species still have taxonomic uncertainties and for others, their natural history does not lend itself to individual pedigree based management (e.g. group living species). DNA-analysis is a key tool to improve knowledge of a population’s genetic make-up and furthermore ensure that, as far as possible, captive populations represent the genetic diversity of the wild counterparts. Thus, DNA-analysis holds great impact on animal health and welfare. In recent years, molecular genetic techniques and tools have become readily available to the zoo and the conservation communities alike. The ongoing technological advances coupled with decreasing prices will create additional opportunities in the near future. But only if genetic samples are available can we make use of these opportunities and open up for a huge range of possibilities for the use of molecular genetics to help improve future management of EAZA ex situ programmes. Adding a genetic layer to a studbook will provide information such as origin and relatedness of founders, which was previously built on assumptions, and help resolve paternity issues. -

Winter/Spring 2018

Winter/Spring 2018 IN THIS ISSUE: Our Mission: EWC Helps Save a Maned Wolf Pup To preserve and protect Mexican wolves, Page 6 red wolves and other wild canid species, EWC Awarded Multiple Recognitions Page 8 with purpose and passion, through EWC Mexican Wolf Makes World History carefully managed breeding, reintroduction Page 10 and inspiring education programs. Arkansas State University and EWC Team Up Page 12 EXECUTIVE DIRECTOR’S MESSAGE 2018 Events Dear Friends of the Endangered Wolf Center Feb. 23 Trivia Collaboration, collaboration, and more collaboration. April 15 This has been the mantra for the Endangered Wolf Center this Volunteer Appreciation past year. Collaboration and partnership are not new to the Dinner Center’s mission, but have risen to the top as a more productive Aug. 25 way to achieve stronger conservation. Polo And our successes are rising as a result. Oct. 20 Over the last five years, I’ve been energized to see many large Wolf Fest non-profit organizations highlight their partnerships and Nov. 17 collaboration with each other. I firmly believe that unity in an Members' Day effort, especially environmental efforts, brings a larger voice to Nov. 24 the issue, and a greater likelihood for success with many working toward one goal. I’d like to Holiday Boutique share with you some of the successes your contributions have helped make possible this year. • Our partners: Our collaboration goes deep with US Fish and Wildlife Service (USFWS), For the latest on events, Arkansas State University, Emerson, Wildlife Rescue Center, zoological facilities near and far, visit our website calendar at schools in the St. -

Zoo Launches Genetic Project to Save Northern White Rhino POSTED by DEBBIE L

ABOUT STAFF CONTACT ADVERTISE FAQ PRIVACY POLICY TERMS OF SERVICE ALL POLITICS CRIME BUSINESS SPORTS EDUCATION ARTS MILITARY TECH LIFE OSPeIaNrcIOh…N LATEST NEWS Homeland Security Funded, But Hunter, Issa Vote 'No' Home » Tech » This Article Zoo Launches Genetic Project to Save Northern White Rhino POSTED BY DEBBIE L. SKLAR ON FEBRUARY 26, 2015 IN TECH | 346 VIEWS | LEAVE A RESPONSE Recommend Share 199 GET TIMES OF SAN DIEGO BY EMAIL Our free newsletter is delivered at 8 a.m. daily. Email Address Nola, a Northern White rhino at the Safari Park at the San Diego Zoo. Photo via The San Diego Zoo SUBSCRIBE With support from the Seaver Institute, geneticists at San Diego Zoo Institute for Conservation Research are taking the initial steps in an effort to use cryopreserved cells to bring back the northern white rhino from the brink of extinction. Living cells banked in the San Diego Zoo’s Frozen Zoo have preserved the genetic lineage of 12 northern white rhinos, including a male that recently passed away at the Safari Park. Scientists hope that new technologies can be used to gather the genetic knowledge needed to create a viable population for this disappearing subspecies, of which only five are left. “Multiple steps must be accomplished to reach the goal of establishing a viable population that can be reintroduced into the species range in Africa, where it is now extinct,” said Oliver Ryder Ph.D., director of genetics for the San Diego Zoo Institute for Conservation Research. “A first step involves sequencing the genomes of northern white rhinos to clarify the extent of genetic divergence from their closest relative, the southern white rhino.” The next step would require conversion of the cells preserved in the Frozen Zoo to stem cells that could develop into sperm and eggs. -

Revised Recovery Plan for the Sihek Or Guam Micronesian Kingfisher (Halcyon Cinnamomina Cinnamomina)

DISCLAIMER Recovery plans delineate actions which the best available science indicates are required to recover and protect listed species. Plans are published by the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service and sometimes prepared with the assistance of recovery teams, contractors, State agencies, and others. Recovery teams serve as independent advisors to the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. Recovery plans are reviewed by the public and submitted to additional peer review before they are approved and adopted by the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. Objectives will be attained and any necessary funds made available subject to budgetary and other constraints affecting the parties involved, as well as the need to address other priorities. Nothing in this plan should be construed as a commitment or requirement that any Federal agency obligate or pay funds in contravention of the Anti-Deficiency Act, 31 USC 1341, or any other law or regulation. Recovery plans do not necessarily represent the views nor the official positions or approval of any individuals or agencies involved in the plan formulation, other than the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. Recovery plans represent the official position of the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service only after they have been signed as approved by the Regional Director or Director. Approved recovery plans are subject to modification as dictated by new findings, changes in species status, and the completion of recovery actions. Please check for updates or revisions at the website addresses provided below before using this plan. Literature citation of this document should read as follows: U.S. -

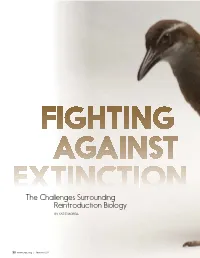

The Challenges Surrounding Reintroduction Biology

The Challenges Surrounding Reintroduction Biology BY KATIE MORELL 22 www.aza.org | January 2016 January 2016 | www.aza.org 23 Listed as extinct in the wild by the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN), the bird has yet to be reintroduced to its native land, so a satellite home for the species has been created on the neighboring Pacific island of Rota— the place where Newland felt his faith in reintroduction falter, if just for a minute. “On my first trip to Rota, I remember stepping off the plane and seeing a rail dead on the ground at the airport,” he said. “Someone had run over it with their car.” The process of reintroducing a species into the wild can be tricky at best. There are hundreds of factors that go into the decision—environmental, political and © Sedgwick County Zoo, Yang Zhao Yang Zoo, © Sedgwick County sociological. When it works, the results are exhilarating for the public and environmentalists. That is what happened in the 1980s when biologists were alerted to the plight of the California condor, pushed to near extinction by a pesticide called DDT. By 1982, there were only 23 condors left; five years later, a robust breeding and reintroduction program was initiated to save the species. The program worked, condors were released, DDT was outlawed and, according to the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service (USFWS), as of 2008 there were t was a few years ago when Scott more condors flying in the wild than in Newland felt his heart drop to managed care. his feet. -

TRANSACTIONS of the Fifty-Seventh North American Wildlife and Natural Resources Conference

TRANSACTIONS of the Fifty-seventh North American Wildlife and Natural Resources Conference Conference theme— Crossroads of Conservation: 500 Years After Columbus Marc/, 27-Apr;V 7. 7992 Radisson Plaza Hotel Charlotte and Charlotte Convention Center Charlotte, North Carolina Edited by Richard E. McCabe i w Published by the Wildlife Management Institute, Washington, DC, 1992 Johnson, M. L. and M, S. Gaines. 1988. Demography of the western harvest mouse, Reithrodon- Managing Genetic Diversity in Captive Breeding tomys megalotis, in eastern Kansas. Oecologia 75:405-411. Kareiva, P. and M, Anderson. 1988. Spatial aspects of .species interactions'. The wedding of models and Reproduction Programs and experiments. In A. Hasting, ed., Community Ecology. Springer-Verlag. New York, NY. Lande, R. 1988. Genetics and demography in biological conservation. Science 241; 1,455-1,460. Levins, R. A. 1980. Extinction. Am. Mathematical Soc. 2:77-107... Katherine Rails and Jonathan D. Ballon Lovejoy, T. B. 1985. Forest fragmentation in the Amazon: A case study. Pages 243-252 in H. Department of Zoological Research Messel, ed., The Study of Populations. Pergamon Press, Sydney, Australia. National Zoological Park Lovejoy, T. E., J. M. Rankin, R. O. Bierregaard, K. S. Brown, L. H. Emmons, and M. E. Van Smithsonian Institution der Voort. 1984. Ecosystem decay of Amazon Forest fragments. Pages 295-325 in M. H. Washington, D.C. Nitecki, ed., Extinctions. Univ. Chicago Press. Chicago, IL. Lovejoy, T. E., R. O. Bierregaard, Jr., A. B. Rylands, J. R. Malcolm, C. E. Quintela, L. H. Harper, K. S. Brown, Jr., A. H. Powell, G. V. N. Powell, H. 0, R. -

Can Cloning Save the White Rhino?

June 14 — June 20,2010 Bloomberg Business week Why analysts are too optimistic \ t \ $135 million in funding from Digital Sky Technologies, the Russian investment Biotechnology firm that also owns as much as 10 per- cent of Facebook. The risk from disgrun- Can Cloning Save tled customers is lawsuits, says Jeremiah The White Rhino? Owyang, an analyst at research firm Al- timeter Group. "Imagine you're a con- sumer and you didn't get the manicure or pedicure you paid for," he says. "Who do you sue, the small business owner or someone who just got $135 million?" Mason says Groupon hasn't been sued for unfulfilled deals, and adds that the company offers customers full refunds if they're dissatisfied. In the coming months, he plans to add online market- ing seminars to better prepare small »•San Diego's Frozen Zoo stores business owners for spikes in demand. cells of endangered species "We say to businesses, the first day is going to be crazy," Mason explains. •"It gives me hope we can help save Mission Minis, a San Francisco bakery species from extinction" that opened in January, was bombarded Fora northern white rhinoceros, of the revenue. The local merchants with 72,000 cupcake orders after a Grou- Angalifu has a pretty sweet life. The two- can set a cap on how much they want pon offer in March. Owner Brandon Ar- ton rhino can roam freely through a 213- to sell. The trouble is, those businesses novick says his frazzled bakers couldn't acre habitat that resembles the African don't always make the cap low enough keep up, making some customers angry. -

Cokids 11.28.14.Indd

ost people in the world can’t digest milk. They can digest milk when Mthey are little babies, but, as they grow older, their bodies stop making lactase, the enzyme that breaks down lactose, the sugar in milk. Drinking Cheese and milk even as toddlers can upset their digestion and make them feel ill. But many Northern Europeans are able to drink milk all their lives, and yogurt were so it was thought that was why they had dairies in ancient times. Now research shows that, when Europeans started dairy farms thousands of years ago, they were lactose intolerant, and had to turn the milk from dairy foods their cows, goats and sheep into cheese and yogurt. That is a process that uses bacteria to break down the lactose and makes the milk digestible. After 4,000 years of eating cheese and yogurt, researchers believe, those before milk ancient dairy farmer’s bodies evolved and began making lactase all their lives so they could fi nally drink fresh milk. Photo/Myrabella CK Reporter Grace Alexander, ColoradoKids Denver October 28, 2014 eXPLoRiNG ouR LocaL PRehisToRY hen you think of the great and ancient di- Wnosaurs what comes to mind? For me, I think of Dinosaur LoW-cosT, LoW-fLYiNG Ridge in Morrison. DRoNes aiD iN The fiGhT aGaiNsT MaLaRia By Thomas Krumholz, 12, a CK Reporter e often hear how loss of from Denver Whabitat can put animals in danger, but, in Malaysia, changes in land use was sus- Celebrating its 25th anniversary, pected of endangering people. the Ridge is world famous for dino- A type of malaria that had not saur fossils, and visiting the Ridge been a human problem had be- again was a great experience. -

Guam Rail Conservation: a Milestone 30 Years in the Making by Kurt Hundgen, Director of Animal Collections

CONSERVATION & RESEARCH UPDATES FROM THE NATIONAL AVIARY SPRING 2021 Guam Rail Conservation: A Milestone 30 Years in the Making by Kurt Hundgen, Director of Animal Collections t the end of 2019 the conservation Working together through the Guam best of all, recent sightings of unbanded world celebrated a momentous Rail Species Survival Plan® (SSP), some rails there confirm that the species has achievement:A Guam Rail, once ‘Extinct twenty zoos strategized ways to ensure the already successfully reproduced in the in the Wild,’ was elevated to ‘Critically genetic diversity and health of this small wild for the first time in almost 40 years. Endangered’ status thanks to the recent population of Guam Rails in human care. The international collaboration that successful reintroduction of the species Their goal was to increase the size of the made the success of the Guam Rail to the wild. This conservation milestone zoo population and eventually introduce reintroduction possible likely will go is more than thirty years in the making— the species onto islands near Guam that down in conservation history. Behind the hoped-for result of intensive remained free of Brown Tree Snakes. every ko’ko’ once again living in the collaboration among multiple zoos and Guam wildlife officials have slowly wild is the very successful collaboration government agencies separated by oceans returned Guam Rails to the wild on the among many organizations and hundreds and continents. It is an extremely rare small neighboring islands of Cocos and of dedicated conservationists. conservation success story, shared by Rota. Reintroduction programs are most And we hope that there will be only one other bird: the iconic successful when local governments and California Condor. -

Iraqi PM Visits Kuwait AS Neighbors Eye Closer Ties

SUBSCRIPTION MONDAY, DECEMBER 22, 2014 SAFAR 30, 1436 AH www.kuwaittimes.net Fees for Muhammad Ali Don’t miss your copy with today’s issue visa renewal hospitalized could with ‘mild’ increase2 pneumonia15 Iraqi PM visits Kuwait as Min 10º Max 20º neighbors eye closer ties High Tide 12:59 & 23:25 Low Tide Abadi thanks Kuwait for deferring compensation 06:23 & 18:07 40 PAGES NO: 16380 150 FILS KUWAIT: Iraqi Prime Minister Haider Al-Abadi and an accompa- No residency for nying delegation arrived in Kuwait yesterday on an official invi- tation by HH the Prime Minister of Kuwait Sheikh Jaber Al- Mubarak Al-Hamad Al-Sabah. Talks between Sheikh Jaber and passports valid Abadi focused on fraternal relations and prospects of bilateral cooperation in various domains in order to serve the common less than a year interests of both countries. The two premiers also exchanged views on their countries’ positions on regional and international KUWAIT: The Interior Ministry’s assistant undersec- issues of mutual interest. Earlier, HH the Amir Sheikh Sabah Al- retary for residency and citizenship affairs Maj Gen Ahmad Al-Jaber Al-Sabah received Abadi at Bayan Palace, where Sheikh Mazen Al-Jarrah said that expatriates’ resi- talks focused on issues pertaining to bilateral relations as well as dency validity would be limited to their passports’ issues of mutual interests. validity. “Those holding passports valid for a year will Abadi later expressed his gratification at the Kuwaiti govern- get one-year residency visa and those holding pass- ment’s acceptance to defer Iraq’s payment of compensation for ports valid for two will get a two-year residency,” he damages incurred as a result of its invasion of Kuwait in 1990. -

I OFFICE of the LEGISLATIVE SECRETARY ( the Honorable Joanne M

CARL T.C. GUTIERREZ GOVERNOR OF GUAM I JUL 1 1 ZNfl I OFFICE OF THE LEGISLATIVE SECRETARY ( The Honorable Joanne M. S. Brown Legislative Secretary I Mina'Bente Singko na Liheslaturan Twenty-Fifth Guam Legislature Suite 200 130 Aspinal Street ~a~iltf&Guam 96910 Dear Legislative Secretary Brown: Enclosed please find Substitute Bill No. 427 (COR), "AN ACT TO REPEAL AND REENACT $1023 OF CHAPTER 10 OF TITLE 1 OF THE GUAM CODE ANNOTATED, RELATIVE TO THE DESIGNATION OF THE OFFICIAL BIRD OF GUAM, which was signed into law Public Law No. 25-155. This legislation changes the officid bird of Guam from the Totot, the Mariana Fruit Dove (Ptilinoppus roseicapilla), to the Ko'ko, the Guam Rail (Gallirallus owstoni). The idea for this change was generated by the Guam Department of Agriculture, which has been involved for a number of years in the effort to preserve and protect the Ko'ko. In fact, the Department of Agriculture had a number of village meetings to determine community feeling, and then their draft legislation was forwarded to the Legislature by the Administration. The Ko'ko has already become something of a symbol for Guam, and was used as a mascot during the South Pacific Games held here last year. I only to Guam, while the Totot is indigenous not only to Guam but also This fact, along with the concentrated local effort to preserve the Ko'ko that effort is now achieving, make it especially appropriate to have official bird of Guam. A portion of Andersen Air Force Base is set free" zone to provide undisturbed habitat to the Ko'ko, and birds and reproducing in the area The Department of Agriculture is habitat area.