Download PDF Datastream

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Midnight Special Songlist

west coast music Midnight Special Please find attached the Midnight Special song list for your review. SPECIAL DANCES for Weddings: Please note that we will need your special dance requests, (I.E. First Dance, Father/Daughter Dance, Mother/Son Dance etc) FOUR WEEKS in advance prior to your event so that we can confirm that the band will be able to perform the song(s) and that we are able to locate sheet music. In some cases where sheet music is not available or an arrangement for the full band is need- ed, this gives us the time needed to properly prepare the music and learn the material. Clients are not obligated to send in a list of general song requests. Many of our clients ask that the band just react to whatever their guests are responding to on the dance floor. Our clients that do provide us with song requests do so in varying degrees. Most clients give us a handful of songs they want played and avoided. Recently, we’ve noticed in increase in cli- ents customizing what the band plays and doesn’t play with very specific detail. If you de- sire the highest degree of control (allowing the band to only play within the margin of songs requested), we ask for a minimum of 100 requests. We want you to keep in mind that the band is quite good at reading the room and choosing songs that best connect with your guests. The more specific/selective you are, know that there is greater chance of losing certain song medleys, mashups, or newly released material the band has. -

Patrizia Sandretto Re Rebaudengo

April 2017 Dylan Lewis, Trans-Figure I Patron, collector and game-changer PATRIZIA SANDRETTO RE REBAUDENGO Mat Collishaw: THE TIME TRAVELLER’S ARTIST Shaking up Australia’s art scene with Danny Goldberg PLUS Classic Week at Christie’s New York APRIL 2017 Contents 062 Letters from Lisbon Take a typographical tour of a city that has stylish signwriting down to a ne art 072 Lit from within Helaine Blumenfeld creates monumental works that seem to glow with an inner life A selection of works and maquettes at Helaine Blumenfeld’s Cambridgeshire studio 082 Queen of Turin With a shrewd eye for emerging talent and a taste for the experimental, collector Patrizia Sandretto Re Rebaudengo has transformed the art scene in her native Italy and beyond 094 God is in the detail Northern Europe’s churches are treasure houses of spectacular limewood sculpture 100 Man on a mission Danny Goldberg wants as many people as possible to see his superb contemporary art collection 110 Nature writ large The South African wilderness is the ideal habitat for the sculptures of Dylan Lewis 120 I bought it at Christie’s Interior designer Edward Bulmer on his passion for an 18th-century religious painting 172 That was then Damien Hirst with Mother and Child (Divided) at the Venice Biennale, 1993 Photo: Nick Ballon. Artworks: © Helaine Blumenfeld, courtesy Artworks: Ballon. Blumenfeld, Nick of the artist © Helaine Photo: and Hignell Gallery [ 008 ] L I T F R O M W ITHIN Helaine Blumenfeld’s abstractions of the human form appear animated, as if by an inner soul. -

Social Network

DEADLINE.com FROM THE BLACK WE HEAR-- MARK (V.O.) Did you know there are more people with genius IQ’s living in China than there are people of any kind living in the United States? ERICA (V.O.) That can’t possibly be true. MARK (V.O.) It is. ERICA (V.O.) What would account for that? MARK (V.O.) Well, first, an awful lot of people live in China. But here’s my question: FADE IN: INT. CAMPUS BAR - NIGHT MARK ZUCKERBERG is a sweet looking 19 year old whose lack of any physically intimidating attributes masks a very complicated and dangerous anger. He has trouble making eye contact and sometimes it’s hard to tell if he’s talking to you or to himself. ERICA, also 19, is Mark’s date. She has a girl-next-door face that makes her easy to fall for. At this point in the conversation she already knows that she’d rather not be there and her politeness is about to be tested. The scene is stark and simple. MARK How do you distinguish yourself in a population of people who all got 1600 on theirDEADLINE.com SAT’s? ERICA I didn’t know they take SAT’s in China. MARK They don’t. I wasn’t talking about China anymore, I was talking about me. ERICA You got 1600? MARK Yes. I could sing in an a Capella group, but I can’t sing. 2. ERICA Does that mean you actually got nothing wrong? MARK I can row crew or invent a 25 dollar PC. -

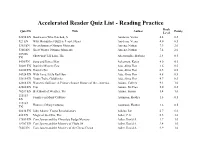

Accelerated Reader Quiz List

Accelerated Reader Quiz List - Reading Practice Book Quiz ID Title Author Points Level 32294 EN Bookworm Who Hatched, A Aardema, Verna 4.4 0.5 923 EN Why Mosquitoes Buzz in People's Ears Aardema, Verna 4.0 0.5 5365 EN Great Summer Olympic Moments Aaseng, Nathan 7.9 2.0 5366 EN Great Winter Olympic Moments Aaseng, Nathan 7.4 2.0 107286 Show-and-Tell Lion, The Abercrombie, Barbara 2.4 0.5 EN 5490 EN Song and Dance Man Ackerman, Karen 4.0 0.5 50081 EN Daniel's Mystery Egg Ada, Alma Flor 1.6 0.5 64100 EN Daniel's Pet Ada, Alma Flor 0.5 0.5 54924 EN With Love, Little Red Hen Ada, Alma Flor 4.8 0.5 35610 EN Yours Truly, Goldilocks Ada, Alma Flor 4.7 0.5 62668 EN Women's Suffrage: A Primary Source History of the...America Adams, Colleen 9.1 1.0 42680 EN Tipi Adams, McCrea 5.0 0.5 70287 EN Best Book of Weather, The Adams, Simon 5.4 1.0 115183 Families in Many Cultures Adamson, Heather 1.6 0.5 EN 115184 Homes in Many Cultures Adamson, Heather 1.6 0.5 EN 60434 EN John Adams: Young Revolutionary Adkins, Jan 6.7 6.0 480 EN Magic of the Glits, The Adler, C.S. 5.5 3.0 17659 EN Cam Jansen and the Chocolate Fudge Mystery Adler, David A. 3.7 1.0 18707 EN Cam Jansen and the Mystery of Flight 54 Adler, David A. 3.4 1.0 7605 EN Cam Jansen and the Mystery of the Circus Clown Adler, David A. -

P. Diddy with Usher I Need a Girl Pablo Cruise Love Will

P Diddy Bad Boys For Life P Diddy feat Ginuwine I Need A Girl (Part 2) P. Diddy with Usher I Need A Girl Pablo Cruise Love Will Find A Way Paladins Going Down To Big Mary's Palmer Rissi No Air Paloma Faith Only Love Can Hurt Like This Pam Tillis After A Kiss Pam Tillis All The Good Ones Are Gone Pam Tillis Betty's Got A Bass Boat Pam Tillis Blue Rose Is Pam Tillis Cleopatra, Queen Of Denial Pam Tillis Don't Tell Me What To Do Pam Tillis Every Time Pam Tillis I Said A Prayer For You Pam Tillis I Was Blown Away Pam Tillis In Between Dances Pam Tillis Land Of The Living, The Pam Tillis Let That Pony Run Pam Tillis Maybe It Was Memphis Pam Tillis Mi Vida Loca Pam Tillis One Of Those Things Pam Tillis Please Pam Tillis River And The Highway, The Pam Tillis Shake The Sugar Tree Panic at the Disco High Hopes Panic at the Disco Say Amen Panic at the Disco Victorious Panic At The Disco Into The Unknown Panic! At The Disco Lying Is The Most Fun A Girl Can Have Panic! At The Disco Ready To Go Pantera Cemetery Gates Pantera Cowboys From Hell Pantera I'm Broken Pantera This Love Pantera Walk Paolo Nutini Jenny Don't Be Hasty Paolo Nutini Last Request Paolo Nutini New Shoes Paolo Nutini These Streets Papa Roach Broken Home Papa Roach Last Resort Papa Roach Scars Papa Roach She Loves Me Not Paper Kites Bloom Paper Lace Night Chicago Died, The Paramore Ain't It Fun Paramore Crush Crush Crush Paramore Misery Business Paramore Still Into You Paramore The Only Exception Paris Hilton Stars Are Bliind Paris Sisters I Love How You Love Me Parody (Doo Wop) That -

Radio Essentials 2012

Artist Song Series Issue Track 44 When Your Heart Stops BeatingHitz Radio Issue 81 14 112 Dance With Me Hitz Radio Issue 19 12 112 Peaches & Cream Hitz Radio Issue 13 11 311 Don't Tread On Me Hitz Radio Issue 64 8 311 Love Song Hitz Radio Issue 48 5 - Happy Birthday To You Radio Essential IssueSeries 40 Disc 40 21 - Wedding Processional Radio Essential IssueSeries 40 Disc 40 22 - Wedding Recessional Radio Essential IssueSeries 40 Disc 40 23 10 Years Beautiful Hitz Radio Issue 99 6 10 Years Burnout Modern Rock RadioJul-18 10 10 Years Wasteland Hitz Radio Issue 68 4 10,000 Maniacs Because The Night Radio Essential IssueSeries 44 Disc 44 4 1975, The Chocolate Modern Rock RadioDec-13 12 1975, The Girls Mainstream RadioNov-14 8 1975, The Give Yourself A Try Modern Rock RadioSep-18 20 1975, The Love It If We Made It Modern Rock RadioJan-19 16 1975, The Love Me Modern Rock RadioJan-16 10 1975, The Sex Modern Rock RadioMar-14 18 1975, The Somebody Else Modern Rock RadioOct-16 21 1975, The The City Modern Rock RadioFeb-14 12 1975, The The Sound Modern Rock RadioJun-16 10 2 Pac Feat. Dr. Dre California Love Radio Essential IssueSeries 22 Disc 22 4 2 Pistols She Got It Hitz Radio Issue 96 16 2 Unlimited Get Ready For This Radio Essential IssueSeries 23 Disc 23 3 2 Unlimited Twilight Zone Radio Essential IssueSeries 22 Disc 22 16 21 Savage Feat. J. Cole a lot Mainstream RadioMay-19 11 3 Deep Can't Get Over You Hitz Radio Issue 16 6 3 Doors Down Away From The Sun Hitz Radio Issue 46 6 3 Doors Down Be Like That Hitz Radio Issue 16 2 3 Doors Down Behind Those Eyes Hitz Radio Issue 62 16 3 Doors Down Duck And Run Hitz Radio Issue 12 15 3 Doors Down Here Without You Hitz Radio Issue 41 14 3 Doors Down In The Dark Modern Rock RadioMar-16 10 3 Doors Down It's Not My Time Hitz Radio Issue 95 3 3 Doors Down Kryptonite Hitz Radio Issue 3 9 3 Doors Down Let Me Go Hitz Radio Issue 57 15 3 Doors Down One Light Modern Rock RadioJan-13 6 3 Doors Down When I'm Gone Hitz Radio Issue 31 2 3 Doors Down Feat. -

Joy Ladin from Through the Door of Life: a Jewish Journey Between Genders

Joy Ladin from Through the Door of Life: A Jewish Journey Between Genders “Why did you have to be a girl?” my youngest asks. It’s spring 2010, almost three years since I moved out. She’s naked and glistening in a bath whose bubbles are disappearing, surrounded by a flotilla of toys – plastic animals, a large submarine, a battered Barbie, an empty vitamin bottle – she alternately buries and resurrects from the fragrant white foam. Her disease has marked her face with a peculiar beauty, blending the cherubic features of a toddler with the serious lines and deep-set eyes of middle age. It’s slowed her physical growth, but so far it hasn’t damaged her brain, kidneys, or heart. She doesn’t realize it, but I look up to her: unlike me, she’s utterly, unapologetically delighted with herself, unscarred by her differences from others, so matter-of-fact in her determination to overcome her physical limitations that I’m not even sure she sees them as limitations. She doesn’t seem to measure herself against her larger, faster, stronger, defter peers. Her delight in herself is part and parcel with her boundless delight in existence. Despite the chromosomal glitches, she’s grown up a lot since I left my family. She’s no longer an inarticulate, uncritically loving three-year-old; at six, she has found words for what she’s lost. Whenever I see her – now it’s only twice a week – she grills me about the motives and morality of my transition. The subject first came up between us when she was five; we were at the tiny local public library, and we both needed to use the bathroom. -

Beyoncé Feminism, Rihanna Womanism: Popular Music and Black Feminist Theory AFR 330, WGS 335 Flags: Cultural Diversity in the US, Global Cultures Spring 2020

The University of Texas at Austin Beyoncé Feminism, Rihanna Womanism: Popular Music and Black Feminist Theory AFR 330, WGS 335 Flags: Cultural Diversity in the US, Global Cultures Spring 2020 Prof: Dr. Traci-Ann Wint Course Description Beyoncé’s fifth live album Homecoming chronicled her performance as the first black woman to headline the Coachella festival. As with Lemonade, the film and performance put Beyoncé’s music in conversation with luminaries such as Toni Morrison and W.E.B. DuBois. Beyoncé’s contemporaries Rihanna and Lizzo similarly center black culture in their music and are unapologetic about their work’s engagement with issues specific to black womanhood. By engaging the music and videos of these and other Black femme recording artists as popular, accessible expressions of African American and Caribbean feminisms, this course explores their contribution to black feminist thought and their impact on global audiences. Beginning with close analysis of these artists’ songs and videos, we read their work in conversation with black feminist theoretical works that engage issues of race, location, violence, economic opportunity, sexuality, standards of beauty, and creative self-expression. The course aims to provide students with an introduction to media studies methodology as well as black feminist theory, and to challenge us to close the gap between popular and academic expressions of black women’s concerns. Course Goals The course aims to provide students with an introduction to Black feminism, Black feminist thought and womanism through an examination of popular culture. At the end of the course students should have a firm grasp on Black Feminist and Womanist theory, techniques in pop culture and media analysis and should be comfortable with the production of scholarly work for a popular audience. -

Karaoke Mietsystem Songlist

Karaoke Mietsystem Songlist Ein Karaokesystem der Firma Showtronic Solutions AG in Zusammenarbeit mit Karafun. Karaoke-Katalog Update vom: 13/10/2020 Singen Sie online auf www.karafun.de Gesamter Katalog TOP 50 Shallow - A Star is Born Take Me Home, Country Roads - John Denver Skandal im Sperrbezirk - Spider Murphy Gang Griechischer Wein - Udo Jürgens Verdammt, Ich Lieb' Dich - Matthias Reim Dancing Queen - ABBA Dance Monkey - Tones and I Breaking Free - High School Musical In The Ghetto - Elvis Presley Angels - Robbie Williams Hulapalu - Andreas Gabalier Someone Like You - Adele 99 Luftballons - Nena Tage wie diese - Die Toten Hosen Ring of Fire - Johnny Cash Lemon Tree - Fool's Garden Ohne Dich (schlaf' ich heut' nacht nicht ein) - You Are the Reason - Calum Scott Perfect - Ed Sheeran Münchener Freiheit Stand by Me - Ben E. King Im Wagen Vor Mir - Henry Valentino And Uschi Let It Go - Idina Menzel Can You Feel The Love Tonight - The Lion King Atemlos durch die Nacht - Helene Fischer Roller - Apache 207 Someone You Loved - Lewis Capaldi I Want It That Way - Backstreet Boys Über Sieben Brücken Musst Du Gehn - Peter Maffay Summer Of '69 - Bryan Adams Cordula grün - Die Draufgänger Tequila - The Champs ...Baby One More Time - Britney Spears All of Me - John Legend Barbie Girl - Aqua Chasing Cars - Snow Patrol My Way - Frank Sinatra Hallelujah - Alexandra Burke Aber Bitte Mit Sahne - Udo Jürgens Bohemian Rhapsody - Queen Wannabe - Spice Girls Schrei nach Liebe - Die Ärzte Can't Help Falling In Love - Elvis Presley Country Roads - Hermes House Band Westerland - Die Ärzte Warum hast du nicht nein gesagt - Roland Kaiser Ich war noch niemals in New York - Ich War Noch Marmor, Stein Und Eisen Bricht - Drafi Deutscher Zombie - The Cranberries Niemals In New York Ich wollte nie erwachsen sein (Nessajas Lied) - Don't Stop Believing - Journey EXPLICIT Kann Texte enthalten, die nicht für Kinder und Jugendliche geeignet sind. -

Song Catalogue February 2020 Artist Title 2 States Mast Magan 2 States Locha E Ulfat 2 Unlimited No Limit 2Pac Dear Mama 2Pac Changes 2Pac & Notorious B.I.G

Song Catalogue February 2020 Artist Title 2 States Mast Magan 2 States Locha_E_Ulfat 2 Unlimited No Limit 2Pac Dear Mama 2Pac Changes 2Pac & Notorious B.I.G. Runnin' (Trying To Live) 2Pac Feat. Dr. Dre California Love 3 Doors Down Kryptonite 3Oh!3 Feat. Katy Perry Starstrukk 3T Anything 4 Non Blondes What's Up 5 Seconds of Summer Youngblood 5 Seconds of Summer She's Kinda Hot 5 Seconds of Summer She Looks So Perfect 5 Seconds of Summer Hey Everybody 5 Seconds of Summer Good Girls 5 Seconds of Summer Girls Talk Boys 5 Seconds of Summer Don't Stop 5 Seconds of Summer Amnesia 5 Seconds of Summer (Feat. Julia Michaels) Lie to Me 5ive When The Lights Go Out 5ive We Will Rock You 5ive Let's Dance 5ive Keep On Movin' 5ive If Ya Getting Down 5ive Got The Feelin' 5ive Everybody Get Up 6LACK Feat. J Cole Pretty Little Fears 7Б Молодые ветра 10cc The Things We Do For Love 10cc Rubber Bullets 10cc I'm Not In Love 10cc I'm Mandy Fly Me 10cc Dreadlock Holiday 10cc Donna 30 Seconds To Mars The Kill 30 Seconds To Mars Rescue Me 30 Seconds To Mars Kings And Queens 30 Seconds To Mars From Yesterday 50 Cent Just A Lil Bit 50 Cent In Da Club 50 Cent Candy Shop 50 Cent Feat. Eminem & Adam Levine My Life 50 Cent Feat. Snoop Dogg and Young Jeezy Major Distribution 101 Dalmatians (Disney) Cruella De Vil 883 Nord Sud Ovest Est 911 A Little Bit More 1910 Fruitgum Company Simon Says 1927 If I Could "Weird Al" Yankovic Men In Brown "Weird Al" Yankovic Ebay "Weird Al" Yankovic Canadian Idiot A Bugs Life The Time Of Your Life A Chorus Line (Musical) What I Did For Love A Chorus Line (Musical) One A Chorus Line (Musical) Nothing A Goofy Movie After Today A Great Big World Feat. -

Emergence of Computers in Manga : from Public to Private Sphere, from Optimistic Futurism to Widespread Uncritical Adoption

Emergence of computers in manga : from public to private sphere, from optimistic futurism to widespread uncritical adoption. Camille Akmut Broad trends in the representation of computer technology in manga history are described, This analysis is based on major, works of the medium, (Umezu’s classic horror The Drifting Classroom to Umaru-chan’s last volume), both pio- neering and uncertain, covering roughly the period from 1970 to 2020. Keywords : art history, manga, capitalism, technology 1 INTRODUCTION The Manga is an underappreciated art form, yet highly useful for the scientist, where meta-memories about contemporary culture are preserved and found. Other than fulfilling the function of telling its own story, the Manga also captures broader changes affecting society : It is this other, less obvious narration that may be of greatest interest to histo- rians and sociologists. No different in this regard from the Novel, the Poem or the Painting, the Manga remains nonetheless a grossly underestimated, and grotesquely neglected medium of art history. In this article we use a selection of well-known titles, picked from various genres in order to attempt an experimental history of the emergence of computers in manga. We find diverging and evolving receptions of the phenomenon, ranging from optimistic futurism to ignorance to full embrace; and an evolution from public to private sphere appearances. Context for the importance of selected works : Of Azumanga Daioh, it can be said that it created or further established all of the tropes of the modern slice-of-life / moe genre : the idiot student (Tomo), the trip to Okinawa (compare with, for instance, Yotsuba’s repeated references to this destination), the foreigner asking for infor- mation e.g. -

100%トーキョー』 上演:2013年11月29日~12月1日 会場:東京芸術劇場 プレイハウス

フェスティバル/トーキョー13 『100%トーキョー』 上演:2013年11月29日~12月1日 会場:東京芸術劇場 プレイハウス Festival/Tokyo 2013 “100% Tokyo” November 29th to December 1st, 2013 Tokyo Metropolitan Theatre, Playhouse 親愛なる東京へ Dear Tokyo, この演劇プロジェクト(?)は統計学的な表象と演劇的な表現のコントラスト This theater project (?) plays with the contrast of statistic representation で遊ぶという試みです。こういった公演は典型的な世論調査同様の制限が and theatrical representation. Performances like this happen within the same limitations like representative public surveys do – they are only based 伴います――というのは、基本的に参加に同意してくださる人々の回答を土 on the answers of people who generally agree to participate. Our team 台にするものだからです。我々のチームはこの町の多様性を反映させるべく、 has undertaken great efforts to provide you with a diversity of participants 多様な方々に参加していただくよう、多大な努力を重ねてきました。従って演 that reflects your diversity. That also meant to avoid or even refuse theater 劇を熱烈に愛している演劇人の参加はご遠慮いただくこともありました。だ enthusiasts. からこそ、あなた方都民を代表している100名の「大使」たちの勇気と寛大さ This is why we especially thank the 100 “ambassadors” of your に感謝したいと思います。彼らの生活そのものが、この公演のためのリハー population for their courage and openness. They have rehearsed for this サルだったのです。ただ自分の経験を重ねるだけで、自分たちの「台詞」を覚 evening by just living their lives. They learned their “lines” by making their えてきました。こういった公演には稽古はありません――ですが、参加者全員 own experiences. A performance like this has not been rehearsed - but just organized so that everyone knows the rules and mechanisms of its various が様々な「ゲーム」のルールや仕組みを知るための構成はあります。舞台に上 “games”. Every evening they decide once again which line they say tonight. がるたびに、そのつど彼らは自分が言う台詞を決めていきます。上演台本はむ The script for this evening is rather a protocol and has been developed in しろ「実施要綱(プロトコル)」であり、参加者とともに作られたものです。こ collaboration with its participants. And it keeps developing throughout the れも公演を重ねていく毎に発展していきます。与えられた選択肢に同意する series of performances. Every evening its 100 protagonists decide afresh か否か、どのグループを選ぶか、100名の主役が舞台上で決めていくのです。 regarding each statement if they will join those who agree or those who disagree.