Chapter Two – Yamani

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

July-September2.Pdf

Tablelands Bushwalking Club Walks Program Tablelands Bushwalking Club Inc, P O Box 1020, Tolga 4882 [email protected] www.tablelandsbushwalking.org Tablelands Bushwalking Club Committee Members President: Sally McPhee 4096 6026 Treasurer: Christine Chambers 0407 344 456 Secretary: Travis Teske 4056 1761 Vice President: Patricia Veivers 4095 4642 Vice President: Tony Sanders 0438 505 394 Activities Officer: Wendy Phillips 4095 4857 Health & Safety Officer Morris Mitchell 4092 2773 Membership Fees: For all members 18 years or more there is a joining fee of $15.00 After that the Tablelands Bushwalking Club offers: Ordinary membership (individual) – where the appropriate joining fee has been paid, including voting rights if aged 18 or more - $25.00. Family membership – where the appropriate joining fee has been paid, membership of a family unit covering the parent/s and dependent children and students under the age of 18, with voting rights limited to the parent/s of the family unit - $50.00 Trip membership (visitor): membership of an individual only for the duration of a single trip, excluding any voting rights - $5.00 Standard Requirements: Boots, high gaiters, sock protectors, hat, sun block, morning and afternoon tea and lunch, at least 2 litres of water, whistle, personal first aid kit. Standard requirements apply to all the walks. Name Tags: These are issued when you join the club. Please attach them to your pack or carry them with you so that you can be identified as a club member. Departure Times: The times given in the program are departure times. Please ensure that you are at the meeting place at least 10 minutes prior to leaving time to sign in, car pool etc. -

Crater Lakes National Park Management Statement 2013

Crater Lakes National Park Management Statement 2013 Legislative framework Park size: 974ha a Nature Conservation Act 1992 Bioregion: Wet Tropics a Environment Protection Biodiversity Conservation Act 1999 (Cwlth) QPWS region: Northern a Aboriginal Cultural Heritage Act 2003 a Wet Tropics World Heritage Protection and Local government Tablelands Regional Management Act 1993 estate/area: Council a Native Title Act 1993 (Cwlth) State electorate: Dalrymple Plans and agreements a Wet Tropics of Queensland World Heritage Area Regional Agreement 2005 a Bonn Agreement a China–Australia Migratory Bird Agreement a Japan–Australia Migratory Bird Agreement a Republic of Korea–Australia Migratory Bird Agreement a Recovery plan for the stream-dwelling rainforest frogs of the Wet Tropics biogeography region of north-east Queensland 2000–2004 a Recovery plan for the southern cassowary Casuarius casuarius johnsonii a National recovery plan for the spectacled flying fox Pteropus conspicillatus Lake Eacham. Photo: Tourism Queensland. a National recovery plan for cave-dwelling bats, Rhinolophus philippinensis, Hipposideros semoni and Taphozous troughtoni 2001–2005 a Draft recovery plan for the spotted-tail quoll (northern sub-species) Dasyurus maculatus gracilis Thematic strategies a Level 2 Fire Strategy a Level 2 Pest Strategy Crater Lakes National Park Management Statement 2013 Vision Crater Lakes National Park continues to protect the unique scenic qualities of the lakes and surrounding rainforest, and the many species of conservation significance that occur there. Crater Lakes National Park continues to be a premier site for tourism, recreation, education and research. It showcases outstanding natural values. Easy vehicular access is provided for park users. Conservation purpose Crater Lakes National Park was formed by the amalgamation of Lake Eacham National Park and Lake Barrine National Park in 1994. -

Holocene Geomagnetic Secular Variation Records from North-Eastern Australian Lake Sediments

Geophys. J. R. astr. Soc. (1985) 81, 103-120 Holocene geomagnetic secular variation records from north-eastern Australian lake sediments c.G. Constable*and M. w. McElhinny?Research School of Earth Sciences, Australian National University, Canberra, ACT 2601, Australia Accepted 1984 September 21. Received 1984 April 25 Summary. Secular variation records have been obtained from cores from Lakes Barrine and Eacham, two north-eastern Australian volcanic crater lakes. The results from several cores have been stratigraphically correlated and then stacked and smoothed. The chronology provided by radiocarbon dating indicates that the Lake Eacham sequence spans the last 5700 calendar years. The time-scale for the Lake Barrine record is less weil constrained but it appears to cover about 1600 to 16 200yr BP. VGP paths for the sites show two periods of anticlockwise motion between about 5710 and 3980 BP and 10500 and 8800 BP. These times correspond to periods of anticlockwise motion in south-eastern Australian records (Barton & McElhinny) and Argentine records (Creer et al.), to within the uncertainties of the assigned time-scales. Introduction Under suitable circumstances fine grained material deposited in lake sediments can provide a record of the ambient geomagnetic field in its depositional or post-depositional remanent magnetization (DRM or PDRM). This record serves to extend knowledge about the geomagnetic field back beyond the age of the earliest historical records, which only span a few centuries in most parts of the world. The sedimentary record is continuous (unlike archaeomagnetic records), but much poorer in quality than that obtained from observatory instruments because of the smoothing inherent in the signal recording process. -

North Qld Wilderness with Bill Peach Journeys

NORTH QLD WILDERNESS WITH BILL PEACH JOURNEYS Sojourn Lakes & Waterfalls of North Queensland 8 Days | 10 Jun – 17 Jun 2019 | AUD$6,995pp twin share | Single Supplement FREE* oin Bill Peach Journeys for an exploration of far north Exclusive Highlights Queensland’s spectacular lakes and waterfalls. From the J magnificent coastal sights of Cape Tribulation, Cooktown, Port Douglas and Cairns to the breathtakingly beautiful creations * Spend 2 nights in the rainforest at Silky Oaks, a of nature to be found inland. We explore the lush green world of Luxury Lodge of Australia the Atherton Tablelands and the hypnotic cascades and revitalising * 1 night at the 5 star Pullman Reef Hotel Cairns natural swimming holes of the famed Waterfall Circuit. Marvel * Enjoy wildlife cruises on the serene Lake Barrine at the natural beauty of waterfalls including the majestic and and iconic Daintree River picturesque Millaa Millaa Falls surrounded by stunning tropical rainforest; be sure to bring your camera along! * Explore spectacular Crater Lake National Park including Lake Eacham We will discover the natural ecosystem which exists in this remarkable * Visit Millaa Millaa Falls, Zillie Falls, Ellinjaa Falls, region while cruising on Lake Barrine and explore Mossman Gorge Malanda Falls on the Waterfall Circuit learning about the unique flora and fauna that abounds. Uncover the region’s timber and mining history in the towns of Atherton * Discover the history of the region in Atherton, and Mareeba and discover Captain Cook and gold rush history Mareeba and Cooktown in Cooktown. Truly an enchanting sojourn of pristine wilderness * Marvel at the natural beauty of Tinaroo Lake, complimented by Bill Peach Journeys style including a two night Mobo Creek Crater, Danbulla Forest, the stay amongst the rainforest at the renowned Silky Oaks Lodge. -

TTT-Trails-Collation-Low-Res.Pdf

A Step Back in Time Pioneering History www.athertontablelands.com.au A Step Back in Time: Pioneering History Mossman Farmers, miners, explorers and Port Douglas soldiers all played significant roles in settling and shaping the Atherton Julatten Tablelands into the diverse region that Cpt Cook Hwy Mount Molloy it is today. Jump in the car and back in Palm Cove Mulligan Hwy time to discover the rich and colourful Kuranda history of the area. Cairns The Mareeba Heritage Museum and Visitor Kennedy HwyBarron Gorge CHILLAGOE SMELTERS National Park Information Centre is the ideal place to begin your Freshwater Creek State exploration of the region’s past. The Museum Mareeba Forest MAREEBA HERITAGE CENTRE showcases the Aboriginal history and early Kennedy Hwy Gordonvale settlement of the Atherton Tablelands, through to influx of soldiers during WW1 and the industries Chillagoe Bruce Hwy Dimbulah that shaped the area. Learn more about the places Bourke Developmental Rd YUNGABURRA VILLAGE Lappa ROCKY CREEK MEMORIAL PARK Tinaroo you’ll visit during your self drive adventure. Kairi Petford Tolga A drive to the township of Chillagoe will reward Yungaburra Lake Barrine Atherton those interested in the mining history of the Lake Eacham ATHERTON/HERBERTON RAILWAY State Forest Kennedy Hwy Atherton Tablelands. The Chillagoe smelters are HOU WANG TEMPLE Babinda heritage listed and offer a wonderful step back in Malanda Herberton - Petford Rd Herberton Wooroonooran National Park time for this once flourishing mining town. HERBERTON MINING MUSUEM Irvinbank Tarzali Lappa - Mt Garnet Rd The Chinese were considered pioneers of MALANDA DAIRY CENTRE agriculture in North Queensland and come 1909 HISTORIC VILLAGE HERBERTON Millaa Millaa Innisfailwere responsible for 80% of the crop production on Mungalli the Atherton Tablelands. -

CCRC and TRC Trail Opportunities

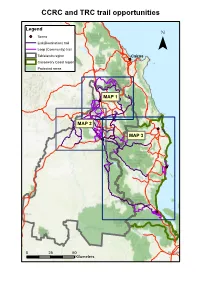

CCRC and TRC tr" ail opportunities Legend Towns Link(Destination) trail Loop (Community) trail ¯ Tablelands region Cairns Cassowary Coast region Protected areas MAP 1 MAP 2 MAP 3 0 25 50 Kilometers Overall CCRC and "TRC trail priorities Legend Towns High Medium ¯ Low Cairns Tablelands region Cassowary Coast region Protected areas Atherton Innisfail Ravenshoe Mission Beach Cardwell 0 25 50 Kilometers TRC trail opportunities: A" therton - Malanda areas Legend Tableland townships ¯ Major roads Link (Destination) trail Loop (Community) trail Protected areas 01.225.5 5 7.5 10 Kilometers 4 3 7 3 35 Walkamin 20 Danbulla Tinaroo 6 3 Tolga Lake Tinaroo Lake Barrine Gadgarra 23 Atherton Yungaburra 7 7 Carrington Lake Eacham 1 2 Peeramon 22 Wongabel Kureen 26 Butchers Creek 27 2 5 North Johnstone Moomin 9 7 Malanda80 Glen Allyn 2 9 30 Upper Barron 81 Herberton 83 8 1 2 3 70 4 32 8 Jaggan 3 8 Topaz 76 8 8 Tarzali 8 5 8 4 9 7 2 9 8 5 3 8 73 6 4 Priorities for construction": Atherton - Malanda areas Legend Tableland townships Major roads ¯ Already constructed High Medium Low Protected areas 01.225.5 5 7.5 10 Kilometers 4 3 7 3 35 Walkamin 20 Danbulla Tinaroo 6 3 Tolga Lake Tinaroo Lake Barrine Gadgarra 23 Atherton Yungaburra 7 7 Carrington Lake Eacham 1 2 Peeramon 22 Wongabel Kureen 26 Butchers Creek 27 2 5 North Johnstone Moomin 9 7 Malanda80 Glen Allyn 2 9 30 Upper Barron 81 Herberton 83 8 1 2 3 70 4 32 8 Jaggan 3 8 Topaz 76 8 8 Tarzali 8 5 8 4 9 7 2 9 8 5 3 8 73 6 4 Priorities for negotiation:" Atherton - Malanda areas Legend Tableland townships -

Traffic Guide Millaa Millaa | Lake Eacham | Yungaburra Welcome to #Tt19

02-04 AUGUST TRAFFIC GUIDE MILLAA MILLAA | LAKE EACHAM | YUNGABURRA WELCOME TO #TT19 Tour of the Tropics is the re-branded Tour of the Tablelands cycling event which has been in operation since 1997. This event is unique - starting in Millaa Millaa on Friday 2nd August and then moving on to Lake Eacham on Saturday 3rd August, with the event culminating in the heart of Yungaburra on Sunday 4th August 2019 for the final stages, Taste of the Tour festival and closing ceremony. All stages will be run on rolling road closures and closed roads. ROLLING ROAD CLOSURES FULL ROAD CLOSURES ROLLING ROAD CLOSURES FULL ROAD CLOSURES Under the rolling road closure for this race, the convoy can Residents affected by road closures as documented in this use both sides of the road and roundabouts, and a sterile brochure are reminded of the following information: zone from vehicles exists from the lead Police to the rear Police, in which no vehicle is permitted to drive for safety During the road closure all driveways will have a traffic reasons. cone placed centre of drive to remind residents of the road Residents encountering the convoy simply need to wait closures, residents needing to enter or exit their properties on the roadside for the convoy to move past quickly and will be required to call the event mobile number provided follow Police instructions. Most times a wait of two to three to request an escort which will be provided by accredited minutes is all that the motorists will have to endure. We moto marshals who will escort vehicles to the nearest exit. -

Journey Guide Atherton and Evelyn Tablelands Parks

Journey guide Atherton and Evelyn tablelands parks Venture delightfully Contents Park facilities ..........................................................................................................ii In the north .......................................................................................................8–9 Welcome .................................................................................................................. 1 In the centre .................................................................................................. 10–11 Maps of the Tablelands .................................................................................2–3 Around Lake Tinaroo ..................................................................................12–13 Plan your journey ................................................................................................ 4 Around Atherton ......................................................................................... 14–15 Getting there ..........................................................................................................5 Heading south ..............................................................................................16–17 Itineraries ............................................................................................................... 6 Southern Tablelands ..................................................................................18–19 Adventurous by nature ......................................................................................7 -

Tropics Tour Guide Handbook: Stage 1 Report

© James Cook University, 2011 Prepared by Julie Carmody, School of Business (Tourism), James Cook University, Cairns ISBN 978-1-921359-66-8 (pdf) To cite this publication: Carmody, J. (2010) Wet Tropics of Queensland World Heritage Area Tour Guide Handbook. Published by the Reef & Rainforest Research Centre Ltd., Cairns (220 pp.). Cover Photographs: Licuala Fan Palm forest – Suzanne Long Tour group – Tourism Queensland 4WD tour – Wet Tropics Management Authority Research to support this Tour Guide Handbook was funded by the Australian Government’s Marine and Tropical Sciences Research Facility, the Wet Tropics Management Authority and James Cook University. The Marine and Tropical Sciences Research Facility (MTSRF) is part of the Australian Government’s Commonwealth Environment Research Facilities programme. The MTSRF is represented in North Queensland by the Reef and Rainforest Research Centre Limited (RRRC). The aim of the MTSRF is to ensure the health of North Queensland’s public environmental assets – particularly the Great Barrier Reef and its catchments, tropical rainforests including the Wet Tropics World Heritage Area, and the Torres Strait – through the generation and transfer of world class research and knowledge sharing. This publication is copyright. The Copyright Act (1968) permits fair dealing for study, research, information or educational purposes subject to inclusion of a sufficient acknowledgement of the source. The views and opinions expressed in this publication are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect those of the Australian Government or the Minister for Sustainability, Environment, Water, Population and Communities. While reasonable effort has been made to ensure that the contents of this publication are factually correct, the Commonwealth does not accept responsibility for the accuracy or completeness of the contents, and shall not be liable for any loss or damage that may be occasioned directly or indirectly through the use of, or reliance on, the contents of this publication. -

Far North District

© The State of Queensland, 2019 © Pitney Bowes Australia Pty Ltd, 2019 © QR Limited, 2015 Based on [Dataset – Street Pro Nav] provided with the permission of Pitney Bowes Australia Pty Ltd (Current as at 12 / 19), [Dataset – Rail_Centre_Line, Oct 2015] provided with the permission of QR Limited and other state government datasets Disclaimer: While every care is taken to ensure the accuracy of this data, Pitney Bowes Australia Pty Ltd and/or the State of Queensland and/or QR Limited makes no representations or warranties about its accuracy, reliability, completeness or suitability for any particular purpose and disclaims all responsibility and all liability (including without limitation, liability in negligence) for all expenses, losses, damages (including indirect or consequential damage) and costs which you might incur as a result of the data being inaccurate or incomplete in any way and for any reason. 142°0'E 144°0'E 146°0'E 148°0'E Badu Island TORRES STRAIT ISLAND Daintree TORRES STRAIT ISLANDS ! REGIONAL COUNCIL PAPUA NEW DAINTR CAIRNS REGION Bramble Cay EE 0 4 8 12162024 p 267 Sue Islet 6 GUINEA 5 RIVE Moa Island Boigu Island 5 R Km 267 Cape Kimberley k Anchor Cay See inset for details p Saibai Island T Hawkesbury Island Dauan Island he Stephens Island ben Deliverance Island s ai Es 267 as W pla 267 TORRES SHIRE COUNCIL 266 p Wonga Beach in P na Turnagain Island G Apl de k 267 re 266 k at o Darnley Island Horn Island Little Adolphus ARAFURA iction Line Yorke Islands 9 Rd n Island Jurisd Rennel Island Dayman Point 6 n a ed 6 li d -

6 Days Savannah Way, Queensland

ITINERARY Savannah Way, Queensland Queensland – Cairns Cairns – Ravenshoe – Georgetown – Normanton – Katherine AT A GLANCE Drive from Cairns, through Queensland’s yourself in the caves of Undara Volcanic lush Tropical Tablelands and historic National Park, the world’s longest lava > Cairns to Atherton (1.5 hours) goldfields, and across the Northern Territory system. Fossick for gold in historic Croydon > Atherton to Georgetown (4 hours) border to Katherine. Walk through World and Georgetown and spot crocodiles in the Heritage-listed rainforest in Kuranda and wetlands around Normantown. Discover > Georgetown to Normanton (5 hours) explore the produce-rich countryside hidden gorges and Aboriginal rock art in > Normanton to Burketown (3 hours) around Mareeba. Visit a century-old Boodjamulla National Park before crossing Chinese temple in Atherton and spend the Central Gulf into the Northern Territory. > Burketown to Borroloola (7 hours) the night in Ravenshoe, Queensland’s From here, the Savannah Way continues > Borroloola to Katherine (9 hours) highest town. Marvel at Millstream Falls, across the outback all the way to Western Australia’s widest waterfalls and lose Australia’s pearling town of Broome. DAY ONE CAIRNS TO ATHERTON Bushwalk and spot rare native birds in wildlife-rich Tolga Scrub into Atherton, in the Mareeba Wetlands and explore the the heart of the scenic Tropical Tablelands. Drive out of tropical Cairns, on the doorstep volcanic rock formations of Granite Gorge. Walk through rainforest and past miniature of north Queensland’s islands, rainforest See Aboriginal rock art galleries in Davies waterfalls for a top-of-the-tablelands view and reef. Bushwalk, visit Barron Falls and Creek National Park or picnic next to the from Halloran’s Hill. -

Atherton and Evelyn Tablelands Parks

Journey guide Atherton and Evelyn tablelands parks Venture delightfully Contents Park facilities ..........................................................................................................ii In the north .......................................................................................................8–9 Welcome .................................................................................................................. 1 In the centre .................................................................................................. 10–11 Maps of the Tablelands .................................................................................2–3 Around Lake Tinaroo ..................................................................................12–13 Plan your journey ................................................................................................ 4 Around Atherton ......................................................................................... 14–15 Getting there ..........................................................................................................5 Heading south ..............................................................................................16–17 Itineraries ............................................................................................................... 6 Southern Tablelands ..................................................................................18–19 Adventurous by nature ......................................................................................7