Bagehot's Lender of Last Resort

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Macroeconomic Effects of Banking Crises Evidence from the United Kingdom, 1750-1938 Kenny, Seán; Lennard, Jason; Turner, John D

The Macroeconomic Effects of Banking Crises Evidence from the United Kingdom, 1750-1938 Kenny, Seán; Lennard, Jason; Turner, John D. 2017 Document Version: Publisher's PDF, also known as Version of record Link to publication Citation for published version (APA): Kenny, S., Lennard, J., & Turner, J. D. (2017). The Macroeconomic Effects of Banking Crises: Evidence from the United Kingdom, 1750-1938. (Lund Papers in Economic History: General Issues; No. 165). Department of Economic History, Lund University. Total number of authors: 3 General rights Unless other specific re-use rights are stated the following general rights apply: Copyright and moral rights for the publications made accessible in the public portal are retained by the authors and/or other copyright owners and it is a condition of accessing publications that users recognise and abide by the legal requirements associated with these rights. • Users may download and print one copy of any publication from the public portal for the purpose of private study or research. • You may not further distribute the material or use it for any profit-making activity or commercial gain • You may freely distribute the URL identifying the publication in the public portal Read more about Creative commons licenses: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/ Take down policy If you believe that this document breaches copyright please contact us providing details, and we will remove access to the work immediately and investigate your claim. LUND UNIVERSITY PO Box 117 221 00 Lund +46 46-222 00 00 Lund Papers in Economic History No. 165, 2017 General Issues The Macroeconomic Effects of Banking Crises: Evidence from the United Kingdom, 1750-1938 Seán Kenny, Jason Lennard & John D. -

Gladstone and the Bank of England: a Study in Mid-Victorian Finance, 1833-1866

GLADSTONE AND THE BANK OF ENGLAND: A STUDY IN MID-VICTORIAN FINANCE, 1833-1866 Patricia Caernarv en-Smith, B.A. Thesis Prepared for the Degree of MASTER OF ARTS UNIVERSITY OF NORTH TEXAS May 2007 APPROVED: Denis Paz, Major Professor Adrian Lewis, Committee Member and Chair of the Department of History Laura Stern, Committee Member Sandra L. Terrell, Dean of the Robert B. Toulouse School of Graduate Studies Caernarven-Smith, Patricia. Gladstone and the Bank of England: A Study in Mid- Victorian Finance, 1833-1866. Master of Arts (History), May 2007, 378 pp., 11 tables, bibliography, 275 titles. The topic of this thesis is the confrontations between William Gladstone and the Bank of England. These confrontations have remained a mystery to authors who noted them, but have generally been ignored by others. This thesis demonstrates that Gladstone’s measures taken against the Bank were reasonable, intelligent, and important for the development of nineteenth-century British government finance. To accomplish this task, this thesis refutes the opinions of three twentieth-century authors who have claimed that many of Gladstone’s measures, as well as his reading, were irrational, ridiculous, and impolitic. My primary sources include the Gladstone Diaries, with special attention to a little-used source, Volume 14, the indexes to the Diaries. The day-to-day Diaries and the indexes show how much Gladstone read about financial matters, and suggest that his actions were based to a large extent upon his reading. In addition, I have used Hansard’s Parliamentary Debates and nineteenth-century periodicals and books on banking and finance to understand the political and economic debates of the time. -

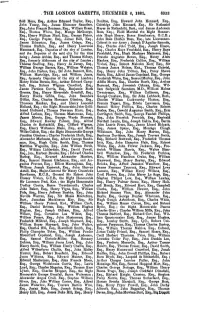

The London Gazette, December 6, 1881

. THE LONDON GAZETTE, DECEMBER 6, 1881. 6553 'field Hora, Esq., Arthur Edmund Taylor, Esq., Doulton, Esq., Howard John Kennard, Esq., John Young, Esq., James Ebenezer Saunders, Coleridge John Kennard, Esq., Sir .Nathaniel Esq., John Francis Bontems, Esq., William Brass, Meyer de Rothschild, Bart, and James Anderson Esq., Thomas "White, Esq., Mungo McGeorge, Rose, Esq.; Field Marshal the Right Honour- Esq., Henry William Nind, Esq., George Fisher, able Hugh Henry, Baron Strathnairn, G.C.B. j Esq., George Pepler, Esq., James Bell, Esq., John Rose Holden Rose, Esq., late Lieutenant- James Edmeston, Esq., James Crispe, Esq., Colonel in our Army ; Joseph D'Aguilar Samuda, Thomas Rudkin, Esq., and Henry Lawrence Esq., Charles John Todd, Esq., Joseph Hoare, Hammack, Esq.. Deputies of the city of London, Esq., Charles Kaye Freshfield, Esq., Henry Raye and the Deputies of the said city for the time Freshfield, Esq., Hugh Mackaye Matheson, Esq., being ; James Abbiss, Esq., and Thomas Sidney, Francis Augustus Bevan, Esq., Henry Alers Esq., formerly Aldermen of the city of London ; Hankey, Esq., Frederick Collier, Esq., William Thomas Snelling, Esq., Henry de Jersey, Esq., Vivian, Esq., Robert Malcolm Kerr, Esq., Sir William George Barnes, Esq., William Webster, Thomas James Nelson, Knt., Thomas Gabriel, Esq., John Parker, Esq., Sir John Bennett, Knt., Esq., Henry John Tritton, Esq., Percy Shawe William Hartridge, Esq., and William Jones, Smith, Esq., Alfred James Copeland, Esq., George Esq., formerly Deputies of the city of London; Frederick White, Esq., Samuel Morley, Esq., John Henry Hulse Berens, Esq., Arthur Edward Camp- Alldin Moore, Esq., Charles Booth, Esq., Arthur bell, Esq., Robert Wigram Crawford, Esq., Burnand, Esq., Jeremiah Colman, Esq., Wil- James Pattison Currie, Esq., Benjamin Buck liam Sedgwick Saunders, M.D., William Holme Greene, Esq., Henry Riversdale Grenfell, Esq., Twentyman, Esq., William Collinson, Esq., Henry Hucks Gibbs, Esq., John Saunders George Croshaw, Esq., Sir John Lubbock. -

Friday, June 21, 2013 the Failures That Ignited America's Financial

Friday, June 21, 2013 The Failures that Ignited America’s Financial Panics: A Clinical Survey Hugh Rockoff Department of Economics Rutgers University, 75 Hamilton Street New Brunswick NJ 08901 [email protected] Preliminary. Please do not cite without permission. 1 Abstract This paper surveys the key failures that ignited the major peacetime financial panics in the United States, beginning with the Panic of 1819 and ending with the Panic of 2008. In a few cases panics were triggered by the failure of a single firm, but typically panics resulted from a cluster of failures. In every case “shadow banks” were the source of the panic or a prominent member of the cluster. The firms that failed had excellent reputations prior to their failure. But they had made long-term investments concentrated in one sector of the economy, and financed those investments with short-term liabilities. Real estate, canals and railroads (real estate at one remove), mining, and cotton were the major problems. The panic of 2008, at least in these ways, was a repetition of earlier panics in the United States. 2 “Such accidental events are of the most various nature: a bad harvest, an apprehension of foreign invasion, the sudden failure of a great firm which everybody trusted, and many other similar events, have all caused a sudden demand for cash” (Walter Bagehot 1924 [1873], 118). 1. The Role of Famous Failures1 The failure of a famous financial firm features prominently in the narrative histories of most U.S. financial panics.2 In this respect the most recent panic is typical: Lehman brothers failed on September 15, 2008: and … all hell broke loose. -

The Bank of England and the Bank Act of 1844 Laurent Le Maux

Central banking and finance: the Bank of England and the Bank Act of 1844 Laurent Le Maux To cite this version: Laurent Le Maux. Central banking and finance: the Bank of England and the Bank Act of1844. Revue Economique, Presses de Sciences Po, 2018. hal-02854521 HAL Id: hal-02854521 https://hal.archives-ouvertes.fr/hal-02854521 Submitted on 8 Jun 2020 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. Central banking and finance: the Bank of England and the Bank Act of 1844 Laurent LE MAUX* May 2020 The literature on the Bank of England Charter Act of 1844 commonly adopts the interpretation that it was a crucial step in the construction of central banking in Great Britain and the analytical framework that contrasts rules and discretion. Through examination of the monetary writings of the period and the Bank of England’s interest rate policy, and also through the systematic analysis of the financial aspect of the 1844 Act, the paper shows that such an interpretation remains fragile. Hence the present paper rests on the articulation between monetary history and the history of economic analysis and also on the institutional approach to money and banking so as to assess the consequences of the 1844 Act for the liquidity market and the relations between the central bank and finance. -

The Historical Role of the European Shadow Banking System in the Development and Evolution of Our Monetary Institutions

CITYPERC Working Paper Series The Historical Role of the European Shadow Banking System in the Development and Evolution of Our Monetary Institutions Israel Cedillo Lazcano CITYPERC Working Paper No. 2013-05 City Political Economy Research Centre [email protected] / @cityperc City, University of London Northampton Square London EC1V 0HB United Kingdom The Historical Role of the European Shadow Banking System in the Development and Evolution of Our Monetary Institutions Israel Cedillo Lazcano* Abstract When we hear about the 2008 Lehman Brothers crisis, immediately we relate it to the concept of “shadow banking system”; however, the credit intermediation involving lightly regulated entities and activities outside the traditional banking system are not new for the European Financial Systems, after all, many innovations developed in the past, were adopted by European nations and exported to the rest of the world (i.e. coinage and central banking), and European innovators unleashed several financial crises related to “shadowy” financial intermediaries (i.e. the Gebroeders de Neufville crisis of 1763). However, despite not many academics, legislators and regulators even agree on what “shadow banking” is, this latter does not refer exclusively to the functions of credit intermediation and maturity transformation. This concept also refers to the creation of assets such as digital media of exchange which are designed under the influence of Friedrich Hayek and the Austrian School of Economics. This lack of a uniform definition of “shadow banking” has limited our regulatory efforts on key issues like the private money creation, a source of vulnerability in the financial system that, paradoxically, at the same time could result in an opportunity to renovate European institutions, heirs of the tradition of the Wisselbank and the Bank of England which, during the seventeenth century, faced monetary innovations and led the European monetary revolution that originated the current monetary and regulatory practices implemented around the world. -

Nber Working Paper Series International Borrowing

NBER WORKING PAPER SERIES INTERNATIONAL BORROWING CYCLES: A NEW HISTORICAL DATABASE Graciela L. Kaminsky Working Paper 22819 http://www.nber.org/papers/w22819 NATIONAL BUREAU OF ECONOMIC RESEARCH 1050 Massachusetts Avenue Cambridge, MA 02138 November 2016 I gratefully acknowledge support from the National Science Foundation (Award No 1023681) and the Institute for New Economic Thinking (Grant No INO14-00009). I want to thank Katherine Carpenter, Samuel Mackey, Jeffrey Messina, Andrew Olenski, and Pablo Vega-García for superb research assistance. The views expressed herein are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the views of the National Bureau of Economic Research. NBER working papers are circulated for discussion and comment purposes. They have not been peer-reviewed or been subject to the review by the NBER Board of Directors that accompanies official NBER publications. © 2016 by Graciela L. Kaminsky. All rights reserved. Short sections of text, not to exceed two paragraphs, may be quoted without explicit permission provided that full credit, including © notice, is given to the source. International Borrowing Cycles: A New Historical Database Graciela L. Kaminsky NBER Working Paper No. 22819 November 2016 JEL No. F30,F34,F65 ABSTRACT The ongoing slowdown in international capital flows has brought again to the attention the booms and bust cycles in international borrowing. Many suggest that capital flow bonanzas are excessive, ending in crises. One of the most frequently mentioned culprits are the cycles of monetary easing and tightening in the financial centers. More recently, the 2008 Subprime Crisis in the United States has also been blamed for the retrenchment in capital flows to both developed and developing countries. -

Whitehall, April^8-, 1842;

Hicks, Walter Anderson Peacock, Robert West- Venables, Josia.h, Wilson, Alfred Wils.cm, . wood, Thomas Quested Finqis, James, Ranishaw, Lea Wilson, Edward Lawford, Peter Laurie, Edward William Stevens, John Atkinson, James Southby Wilson, Richard Lea Wilson, Robert Ellis, William Bridge, John Brown, Edward Godson, Thomas Peters, James Walkinshaw, Joseph Somes, jun., Pewtress, Joshua Thomas Bedford, Henry John Samuel Gregson, William Hughes Hughes, jun., Eltnes, John William tipss, William Muddel), Henry Alexander Rogers, George Magnay, John Master- Prichard, Benjamin Stubbing, Henry Smith, man, jun., Daniel Mildred, Frederick Mildred, John. • Thomas Watkins, and George Wright, Esqi's., Meek Britten, Richard Lambert Jones, David Wij- Deputies of • the city of London, and the liams Wire, Charles Pearson, Thomas Saunder?, and. Deputies thereof for the time being ; John Garratt, James Cosmo Melville, Esqrs. Edward Tickner, Robert Williams, James Brogden, and Stephen Edward Thornton, Esqis., Sir Thomas Neave, Bart., Jeremiah Olive, Jeremiah Harman, ' Isaac Solly, Andrew Loughnan, Abel Chapman, Whitehall, April 25, 1842. Cornelius Buller, Wilj'mm Ward, and Melvil Wilson, . Esqrs,, Sir John Henry Felly, Bart., William Cotton, .The Queen has been graciously pleased, 'np'-n Robert Barclay, Edward Henry Chapman, Henry the nomination of his Grace the Duke of NorioJk, Davidson, Charles Pasr.oe Grenfell, Abel Lewes Earl Marshaland Hereditary Marshal of England,. Gower, Thomson Hankey, junr., John Oliver to appoint Edward Howard Gibbon, Esq. Moworay. Hanson, John Benjamin Heath, Kirkman Daniel Herald of Arms Extraordinary. • Hodgson, Charles Frederick Hiith, Alfred Latham, James Malcolmson, • Jauies Morris, Sheffield .Neave, George Warde. Norman, John .Horsley Palmer, James Pattison, • Christopher Pearse, Henry James Foreign-Office, May, 2, 1842: , Prescdtt, and Charles Pole, Esqrs., Sir John Rae Read, Bart., William R. -

The Foundations of the Valuation of Insurance Liabilities

The foundations of the valuation of insurance liabilities Philipp Keller 14 April 2016 Audit. Tax. Consulting. Financial Advisory. Content • The importance and complexity of valuation • The basics of valuation • Valuation and risk • Market consistent valuation • The importance of consistency of market consistency • Financial repression and valuation under pressure • Hold-to-maturity • Conclusions and outlook 2 The foundations of the valuation of insurance liabilities The importance and complexity of valuation 3 The foundations of the valuation of insurance liabilities Valuation Making or breaking companies and nations Greece: Creative accounting and valuation and swaps allowed Greece to satisfy the Maastricht requirements for entering the EUR zone. Hungary: To satisfy the Maastricht requirements, Hungary forced private pension-holders to transfer their pensions to the public pension fund. Hungary then used this pension money to plug government debts. Of USD 15bn initially in 2011, less than 1 million remained at 2013. This approach worked because the public pension fund does not have to value its liabilities on an economic basis. Ireland: The Irish government issued a blanket state guarantee to Irish banks for 2 years for all retail and corporate accounts. Ireland then nationalized Anglo Irish and Anglo Irish Bank. The total bailout cost was 40% of GDP. US public pension debt: US public pension debt is underestimated by about USD 3.4 tn due to a valuation standard that grossly overestimates the expected future return on pension funds’ asset. (FT, 11 April 2016) European Life insurers: European life insurers used an amortized cost approach for the valuation of their life insurance liability, which allowed them to sell long-term guarantee products. -

How to Prevent a Banking Panic: the Barings Crisis of 1890

How to Prevent a Banking Panic: the Barings Crisis of 1890 Financial histories have treated the Barings Crisis of 1890 as a minor or pseudo-crisis with no threat to the systems of payment and settlement. New evidence reveals that Baring Brothers was not simply suffering from a temporary liquidity problem but was an insolvent institution. Just as knowledge of its true condition was revealed and a full-scale panic was about to ignite, the Bank of England stepped in: but it did not respond as Bagehot recommended---and is generally believed. Instead of waiting for the panic to break and then lending freely at a high rate on good collateral, the Bank organized a pre-emptive lifeboat operation. A large domestic financial crisis was avoided, while effective steps were taken to mitigate the effects of moral hazard from this discretionary intervention. Eugene N. White Rutgers University and NBER Department of Economics New Brunswick, NJ 08901, USA [email protected] Economic History Association September 16-18, 2016 0 Since the failure of Northern Rock in the U.K. and the collapse of Baer Sterns, Lehman Brothers and AIG in the U.S. in 2007-2008, arguments have intensified over whether central banks should follow a Bagehot-style policy in a financial crisis or intervene to save a failing SIFI (systemically important financial institution). In this debate, the experience of central banks during the classical gold standard is regarded as crucially informative. Most scholars have concluded that the Bank of England eliminated panics by strictly following Walter Bagehot’s dictum in Lombard Street (1873) to lend freely at a high rate of interest on good collateral in a crisis. -

Mihm-Stephen -Roubini-Nouriel-Crisis

ABC Amber ePub Converter Trial version, http://www.processtext.com/abcepub.html Page 1 ABC Amber ePub Converter Trial version, http://www.processtext.com/abcepub.html THE PENGUIN PRESS Published by the Penguin Group Penguin Group (USA) Inc., 375 Hudson Street, New York, New York 10014, U.S.A. Penguin Group (Canada), 90 Eglinton Avenue East, Suite 700, Toronto, Ontario, Canada M4P 2Y3 (a division of Pearson Penguin Canada Inc.) Penguin Books Ltd, 80 Strand, London WC2R 0RL, England Penguin Ireland, 25 St. Stephen’s Green, Dublin 2, Ireland (a division of Penguin Books Ltd) Penguin Books Australia Ltd, 250 Camberwell Road, Camberwell, Victoria 3124, Australia (a division of Pearson Australia Group Pty Ltd) • Penguin Books India Pvt Ltd, 11 Community Centre, Panchsheel Park, New Delhi-110 017, India Penguin Group (NZ), 67 Apollo Drive, Rosedale, North Shore 0632, New Zealand (a division of Pearson New Zealand Ltd) Penguin Books (South Africa) (Pty) Ltd, 24 Sturdee Avenue, Rosebank, Johannesburg 2196, South Africa Penguin Books Ltd, Registered Offices: 80 Strand, London WC2R 0RL, England First published in 2010 by The Penguin Press, a member of Penguin Group (USA) Inc. Copyright © Nouriel Roubini and Stephen Mihm, 2010 All rights reserved Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Roubini, Nouriel. Crisis economics : a crash course in the future of finance / Nouriel Roubini and Stephen Mihm. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references and index. eISBN : 978-1-101-42742-2 1. Financial crises. 2. Business cycles. 3. Economics. I. Mihm, Stephen, 1968- II. Title. HB3722.R68 2010 338.5’42—dc22 2009053925 Without limiting the rights under copyright reserved above, no part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in or introduced into a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means (electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise), without the prior written permission of both the copyright owner and the above publisher of this book. -

How to Prevent a Banking Panic: the Barings Crisis of 1890

How to Prevent a Banking Panic: the Barings Crisis of 1890 Eugene N. White Rutgers University and NBER Department of Economics New Brunswick, NJ 08901, USA [email protected] 175 Years of The Economist A Conference on Economics and the Media London, September 24-25, 2015 0 Since the failure of Northern Rock in the U.K. and the collapse of Baer Sterns, Lehman Brothers and AIG in the U.S. in 2007-2008, arguments have intensified over whether central banks should follow a Bagehot-style policy in a financial crisis or intervene to save a failing SIFI (systemically important financial institution). In this debate, the experience of central banks during the classical gold standard is regarded as crucially informative. Most scholars have concluded that the Bank of England eliminated panics by strictly following Walter Bagehot’s dictum in Lombard Street (1873) to lend freely at a high rate of interest on good collateral in a crisis. This paper re-examines the first major threat to British financial stability after the publication of Lombard Street, the Barings Crisis of 1890. Previous financial histories have treated it as a minor crisis, arising from a temporary liquidity problem that posed no threat to the systems of payment and settlement. However, contemporaries believed that a panic would engulf the financial system if Baring Brothers & Co., Britain’s second largest merchant/investment bank and a highly interconnected global institution, collapsed. New evidence reveals that this SIFI was a deeply insolvent bank whose true condition was obscured in the effort to halt a panic.