A Computer-Assisted Rhetorical Criticism of the Message of Harry F

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

N Russia with Love Minisces About R,Ussian Revolution and Living in America

Page 11 Verities and balderdash sung at Painter's. Mill by Patrick Pannella As a single beam of light casts a such as "Cats In The Cradle ","Mr. Tanner", All my life's a circle. shimmering glow over the revolving stage, "Taxi", and "Sequel (To Taxi)", or Tom Sunrise and sun'down. Harry Chapin squints. He clenches his plain Chapin lending his high-pitched voice to The moon rose through the nighttime, wooden guitar in one hand, and he squints sj}ngs like. "Make a Wish", the Chapin Till the daybreak comes around. again. When his free hand ceases to ramble brothers move with the music. Like the All my life's a circle, through his wavy brown hair, he begins to crowd, they seem to be i7ll0 the songs. But I can't tell you why. sing. The near sellout crowd grows silent. The entertainers frequently encourage the The season's spinning around again, Like a trapped lion confronted with an open audience to sing along, especially in the song The years keep rolling by. cage, the words spring out; "30,000 Pounds of Bananas". This appears And the wind will whip your tousled hair.Y to be one song where meaning lacks a-peel, Answers are not important here. It's the The sun, the rain, the sweet despair, so to speak. It also proves to be a fun question" which are raised that have Great tales of love and strife. breather. for the two. The performance ends meaning. They are the questions which And somewhere on your path to glory, with a couple of verses from "Circle". -

Mow!,'Mum INN Nn

mow!,'mum INN nn %AUNE 20, 1981 $2.75 R1-047-8, a.cec-s_ Q.41.001, 414 i47,>0Z tet`44S;I:47q <r, 4.. SINGLES SLEEPERS ALBUMS COMMODORES.. -LADY (YOU BRING TUBES, -DON'T WANT TO WAIT ANY- POINTER SISTERS, "BLACK & ME UP)" (prod. by Carmichael - eMORE" (prod. by Foster) (writers: WHITE." Once again,thesisters group) (writers: King -Hudson - Tubes -Foster) .Pseudo/ rving multiple lead vocals combine witt- King)(Jobete/Commodores, Foster F-ees/Boone's Tunes, Richard Perry's extra -sensory sonc ASCAP) (3:54). Shimmering BMI) (3 50Fee Waybill and the selection and snappy production :c strings and a drying rhythm sec- ganc harness their craziness long create an LP that's several singles tionbackLionelRichie,Jr.'s enoughtocreate epic drama. deep for many formats. An instant vocal soul. From the upcoming An attrEcti.e piece for AOR-pop. favoriteforsummer'31. Plane' "In the Pocket" LP. Motown 1514. Capitol 5007. P-18 (E!A) (8.98). RONNIE MILSAI3, "(There's) NO GETTIN' SPLIT ENZ, "ONE STEP AHEAD" (prod. YOKO ONO, "SEASON OF GLASS." OVER ME"(prod.byMilsap- byTickle) \rvriter:Finn)(Enz. Released to radio on tape prior to Collins)(writers:Brasfield -Ald- BMI) (2 52. Thick keyboard tex- appearing on disc, Cno's extremel ridge) {Rick Hall, ASCAP) (3:15). turesbuttressNeilFinn'slight persona and specific references tc Milsap is in a pop groove with this tenor or tit's melodic track from her late husband John Lennon have 0irresistible uptempo ballad from the new "Vlaiata- LP. An air of alreadysparkedcontroversyanci hisforthcoming LP.Hissexy, mystery acids to the appeal for discussion that's bound to escaate confident vocal steals the show. -

ANNUAL REPORT 2015 Closing the Hunger Gap Conference, Oregon

The Healing Garden at Far Rock Farm, New York ANNUAL REPORT 2015 Closing the Hunger Gap Conference, Oregon Partnering with WhyHunger was a pivotal moment for us as a small, often unconventional, hunger relief organization in the Midwest. WhyHunger connects us with like-minded, innovative organizations across the country, challenges us to be critical of our role in the emergency food system, and inspires us to continuously improve.” – Amanda Nickey, President & Chief Executive Officer, Mother Hubbard’s Cupboard MESSAGE FROM THE EXECUTIVE DIRECTOR Dear Friends, With one year as the executive director under my belt, solve hunger over the long-term. Over the years, we’ve I feel honored and excited to be working with our staff, connected millions of hungry people to healthy food board, grassroots partners and you to lead such an and we have invested millions of dollars in grassroots incredible organization. Harry Chapin and Bill Ayres started organizations that are training, empowering and nourishing WhyHunger in 1975 to move beyond food charity and their communities. We won’t stop there. We are working to address the social justice issues at the core of hunger. We change the systems and structures that perpetuate hunger remain true to that mission today. We stand in solidarity and poverty. We are fueling innovation on the community, with our community-based partners all around the globe regional, national and global level at the intersections and listen to their wisdom to inform our work. Together of hunger and health, race, the economy and the we move our strategy forward to tackle the root causes of environment. -

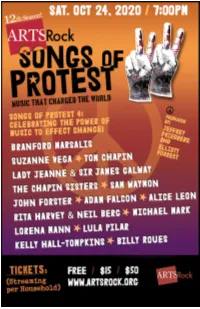

Songs-Of-Protest-2020.Pdf

Elliott Forrest Dara Falco Executive & Artistic Director Managing Director Board of Trustees Stephen Iger, President Melanie Rock, Vice President Joe Morley, Secretary Tim Domini, Treasurer Karen Ayres Rod Greenwood Simon Basner Patrick Heaphy David Brogno James Sarna Hal Coon Lisa Waterworth Jeffrey Doctorow Matthew Watson SUPPORT THE ARTS Donations accepted throughout the show online at ArtsRock.org The mission of ArtsRock is to provide increased access to professional arts and multi-cultural programs for an underserved, diverse audience in and around Rockland County. ArtsRock.org ArtsRock is a 501 (C)(3) Not For-Profit Corporation Dear Friends both Near and Far, Welcome to SONGS OF PROTEST 4, from ArtsRock.org, a non- profit, non-partisan arts organization based in Nyack, NY. We are so glad you have joined us to celebrate the power of music to make social change. Each of the first three SONGS OF PROTEST events, starting in April of 2017, was presented to sold-out audiences in our Rockland, NY community. This latest concert, was supposed to have taken place in-person on April 6th, 2020. We had the performer lineup and songs already chosen when we had to halt the entire season due to the pandemic. As in SONGS OF PROTEST 1, 2 & 3, we had planned to present an evening filled with amazing performers and powerful songs that have had a historical impact on social justice. When we decided to resume the series virtually, we rethought the concept. With so much going on in our country and the world, we offered the performers the opportunity to write or present an original work about an issue from our current state of affairs. -

The Twenty Greatest Music Concerts I've Ever Seen

THE TWENTY GREATEST MUSIC CONCERTS I'VE EVER SEEN Whew, I'm done. Let me remind everyone how this worked. I would go through my Ipod in that weird Ipod alphabetical order and when I would come upon an artist that I have seen live, I would replay that concert in my head. (BTW, since this segment started I no longer even have an ipod. All my music is on my laptop and phone now.) The number you see at the end of the concert description is the number of times I have seen that artist live. If it was multiple times, I would do my best to describe the one concert that I considered to be their best. If no number appears, it means I only saw that artist once. Mind you, I have seen many artists live that I do not have a song by on my Ipod. That artist is not represented here. So although the final number of concerts I have seen came to 828 concerts (wow, 828!), the number is actually higher. And there are "bar" bands and artists (like LeCompt and Sam Butera, for example) where I have seen them perform hundreds of sets, but I counted those as "one," although I have seen Lecompt in "concert" also. Any show you see with the four stars (****) means they came damn close to being one of the Top Twenty, but they fell just short. So here's the Twenty. Enjoy and thanks so much for all of your input. And don't sue me if I have a date wrong here and there. -

Songs by Title Karaoke Night with the Patman

Songs By Title Karaoke Night with the Patman Title Versions Title Versions 10 Years 3 Libras Wasteland SC Perfect Circle SI 10,000 Maniacs 3 Of Hearts Because The Night SC Love Is Enough SC Candy Everybody Wants DK 30 Seconds To Mars More Than This SC Kill SC These Are The Days SC 311 Trouble Me SC All Mixed Up SC 100 Proof Aged In Soul Don't Tread On Me SC Somebody's Been Sleeping SC Down SC 10CC Love Song SC I'm Not In Love DK You Wouldn't Believe SC Things We Do For Love SC 38 Special 112 Back Where You Belong SI Come See Me SC Caught Up In You SC Dance With Me SC Hold On Loosely AH It's Over Now SC If I'd Been The One SC Only You SC Rockin' Onto The Night SC Peaches And Cream SC Second Chance SC U Already Know SC Teacher, Teacher SC 12 Gauge Wild Eyed Southern Boys SC Dunkie Butt SC 3LW 1910 Fruitgum Co. No More (Baby I'm A Do Right) SC 1, 2, 3 Redlight SC 3T Simon Says DK Anything SC 1975 Tease Me SC The Sound SI 4 Non Blondes 2 Live Crew What's Up DK Doo Wah Diddy SC 4 P.M. Me So Horny SC Lay Down Your Love SC We Want Some Pussy SC Sukiyaki DK 2 Pac 4 Runner California Love (Original Version) SC Ripples SC Changes SC That Was Him SC Thugz Mansion SC 42nd Street 20 Fingers 42nd Street Song SC Short Dick Man SC We're In The Money SC 3 Doors Down 5 Seconds Of Summer Away From The Sun SC Amnesia SI Be Like That SC She Looks So Perfect SI Behind Those Eyes SC 5 Stairsteps Duck & Run SC Ooh Child SC Here By Me CB 50 Cent Here Without You CB Disco Inferno SC Kryptonite SC If I Can't SC Let Me Go SC In Da Club HT Live For Today SC P.I.M.P. -

Songs by Title

Songs by Title Title Artist Title Artist #1 Goldfrapp (Medley) Can't Help Falling Elvis Presley John Legend In Love Nelly (Medley) It's Now Or Never Elvis Presley Pharrell Ft Kanye West (Medley) One Night Elvis Presley Skye Sweetnam (Medley) Rock & Roll Mike Denver Skye Sweetnam Christmas Tinchy Stryder Ft N Dubz (Medley) Such A Night Elvis Presley #1 Crush Garbage (Medley) Surrender Elvis Presley #1 Enemy Chipmunks Ft Daisy Dares (Medley) Suspicion Elvis Presley You (Medley) Teddy Bear Elvis Presley Daisy Dares You & (Olivia) Lost And Turned Whispers Chipmunk Out #1 Spot (TH) Ludacris (You Gotta) Fight For Your Richard Cheese #9 Dream John Lennon Right (To Party) & All That Jazz Catherine Zeta Jones +1 (Workout Mix) Martin Solveig & Sam White & Get Away Esquires 007 (Shanty Town) Desmond Dekker & I Ciara 03 Bonnie & Clyde Jay Z Ft Beyonce & I Am Telling You Im Not Jennifer Hudson Going 1 3 Dog Night & I Love Her Beatles Backstreet Boys & I Love You So Elvis Presley Chorus Line Hirley Bassey Creed Perry Como Faith Hill & If I Had Teddy Pendergrass HearSay & It Stoned Me Van Morrison Mary J Blige Ft U2 & Our Feelings Babyface Metallica & She Said Lucas Prata Tammy Wynette Ft George Jones & She Was Talking Heads Tyrese & So It Goes Billy Joel U2 & Still Reba McEntire U2 Ft Mary J Blige & The Angels Sing Barry Manilow 1 & 1 Robert Miles & The Beat Goes On Whispers 1 000 Times A Day Patty Loveless & The Cradle Will Rock Van Halen 1 2 I Love You Clay Walker & The Crowd Goes Wild Mark Wills 1 2 Step Ciara Ft Missy Elliott & The Grass Wont Pay -

(Pdf) Download

Artist Song 2 Unlimited Maximum Overdrive 2 Unlimited Twilight Zone 2Pac All Eyez On Me 3 Doors Down When I'm Gone 3 Doors Down Away From The Sun 3 Doors Down Let Me Go 3 Doors Down Behind Those Eyes 3 Doors Down Here By Me 3 Doors Down Live For Today 3 Doors Down Citizen Soldier 3 Doors Down Train 3 Doors Down Let Me Be Myself 3 Doors Down Here Without You 3 Doors Down Be Like That 3 Doors Down The Road I'm On 3 Doors Down It's Not My Time (I Won't Go) 3 Doors Down Featuring Bob Seger Landing In London 38 Special If I'd Been The One 4him The Basics Of Life 98 Degrees Because Of You 98 Degrees This Gift 98 Degrees I Do (Cherish You) 98 Degrees Feat. Stevie Wonder True To Your Heart A Flock Of Seagulls The More You Live The More You Love A Flock Of Seagulls Wishing (If I Had A Photograph Of You) A Flock Of Seagulls I Ran (So Far Away) A Great Big World Say Something A Great Big World ft Chritina Aguilara Say Something A Great Big World ftg. Christina Aguilera Say Something A Taste Of Honey Boogie Oogie Oogie A.R. Rahman And The Pussycat Dolls Jai Ho Aaliyah Age Ain't Nothing But A Number Aaliyah I Can Be Aaliyah I Refuse Aaliyah Never No More Aaliyah Read Between The Lines Aaliyah What If Aaron Carter Oh Aaron Aaron Carter Aaron's Party (Come And Get It) Aaron Carter How I Beat Shaq Aaron Lines Love Changes Everything Aaron Neville Don't Take Away My Heaven Aaron Neville Everybody Plays The Fool Aaron Tippin Her Aaron Watson Outta Style ABC All Of My Heart ABC Poison Arrow Ad Libs The Boy From New York City Afroman Because I Got High Air -

Easter Resources (Selected Titles – More Will Be Added) Available To

Easter Resources (selected titles – more will be added) available to borrow from the United Media Resource Center http://www.igrc.org/umrc Contact Jill Stone at 217-529-2744 or by e-mail at [email protected] or search for and request items using the online catalog Key to age categories: P = preschool e = lower elementary (K-Grade 3) E = upper elementary (Grade 4-6) M = middle school/ junior high H = high school Y = young adult A = adult (age 30-55) S = adult (age 55+) DVDs: 24 HOURS THAT CHANGED THE WORLD (120032) Author: Hamilton, Adam. This seven-session DVD study will help you better understand the events that occurred during the last 24 hours of Jesus' life; to see more clearly the theological significance of Christ's suffering and death; and to reflect upon the meaning of these events for your life. DVD segments: Introduction (1 min.); 1) The Last Supper (11 min.); 2) The Garden of Gethsemane (7 min.); 3) Condemned by the Righteous (9 min.); 4) Jesus, Barabbas, and Pilate (9 min.); 5) The Torture and Humiliation of the King (9 min.); 6) The Crucifixion (13 min.); 7) Christ the Victor (11 min.); Bonus: What If Judas Had Lived? (5 min.); Promotional segment (1 min.). Includes leader's guide and hardback book. Age: YA. 77 Minutes. Related book: 24 HOURS THAT CHANGED THE WORLD: 40 DAYS OF REFLECTION (811018) Author: Hamilton, Adam. In this companion volume that can also function on its own, Adam Hamilton offers 40 days of reflection and meditation enabling us to pause, dig deeper, and emerge changed forever. -

Tal Og Perspektiver MUSIKSELSKABERFOTO: WIFOPRO.DK 2016 - TAL OG PERSPEKTIVER S

MUSIK- SELSKABER 2016 tal og perspektiver MUSIKSELSKABERFOTO: WIFOPRO.DK 2016 - TAL OG PERSPEKTIVER S. 2 FORORD I mere end et århundrede har man kunnet høre musik Løsningen ligger imidlertid lige for. Den europæiske i de danske hjem. I starten af 1900-tallet var det dog lovgivning – og særligt den aktuelle reform af ophavs- kun de velbjærgede borgere forundt at opleve grammo- retten – bør understrege, at alle tjenester, der aktivt fonen frembringe lyd i stuen. På daværende tidspunkt udbyder musik, selvfølgelig skal indhente tilladelse fra kostede en grammofon nemlig mere end en månedsløn dem, der leverer musikken, før den kan udbydes. Også for de fleste danskere. amerikanske giganter som YouTube, der baserer de- res succesfulde forretningsmodel på, at brugerne selv Sådan er det heldigvis ikke i dag. Tværtimod kan alle uploader musik til tjenesten. nu få adgang til millioner af musiknumre med en lav månedlig ydelse og få klik på mobilen. Forbruget af Det er bekymrende, at artister, sangskrivere og mu- indspillet musik har således næppe været større, end sikselskaber ikke får en anstændig betaling for deres det er i dag. hårde arbejde fra sådanne tjenester i dag. Mindst lige så bekymrende er det imidlertid, at konkurrencesitua- Derfor er det ikke med udelt begejstring, vi kan konsta- tionen mellem tjenesterne er så grotesk, at den reelt er tere, at musikselskabernes indtægter for salg af ind- en bombe under udviklingen af nye spændende mulig- spillet musik udgør 494 mio. kr. i 2016. For selvom der heder til forbrugerne. er tale om en vækst på 9 % sammenlignet med 2015, burde markedet være markant større, når man ser på For hvor er incitamentet til videreudvikling hos tje- det faktiske forbrug af musik i Danmark. -

Lent & Easter Resources

LENT & EASTER RESOURCES from the Resource Center January 2019 The SC Conference Resource Center is your connection to VHS tapes, DVD's and seasonal musicals. We are here to serve your church family. To reserve resources, call 1-803-786-9486. CHILDREN – DVD/VIDEO continues with the drama of Christ's betrayal, arrest and crucifixion—and his triumphant resurrection and ascent into Heaven. Age: PeE CHERUB WINGS: AND IT WAS SO (DVD176EC) 25 min./ 2000. In this Easter episode, a rousing space-chase in cherub JEREMY’S EGG (DVD1568EC) 95 min./1999. Twelve-year- chariots topples Cherub and Chubby into an awesome awareness old Jeremy is terminally ill and the only special-needs child in of God’s mighty power. Children will see the ultimate act of second grade. His teacher gives her students plastic eggs with the forgiveness in the crucifixion and the power of God in the instructions to fill them with something that symbolizes Easter Resurrection. This program shows how we can benefit from and new life. Jeremy's response to the assignment astonishes her, God’s daily presence in our lives. Ages 3-7. Age: PeE. his classmates, and the Navy pilot who is his friend. Based on a true story. Age: eEMHYAS. CHILDREN'S HEROES OF THE BIBLE: #2 NEW TESTAMENT (DVD1276C) 7 stories, 23 min. each. Animated READ AND SHARE BIBLE: EASTER (DVD1292EC) 30 Bible stories designed with a child's viewing habits in mind, and min./ 2010. Animated straight from the pages of the popular Read based squarely on Biblical accounts and interpreted at a child's and Share® Bible, this story of Easter is an uninterrupted half- level. -

Tom Chapin's Biography

Tom Chapin's Biography Born March 13, 1945, in New York, NY; father was a jazz drummer; married wife Bonnie, 1976; children: Abigail, Lily. Education: State University College at Plattsburgh, B.A. in history, 1969. Addresses: Record company-- Sundance Music, P.O. Box 1663, New York, NY 10011. Tom Chapin's early career may have been overshadowed by that of his more famous brother, singer-songwriter Harry Chapin of "Cat's in the Cradle" and "Taxi" fame, but Tom has made quite a name for himself as an eclectic songwriter and singer nonetheless. By the early 1990s, in fact, his music written especially for children, with its toe-tapping tunes and rich guitar accompaniments, had pleased parents so well that they generally think of his later body of work as "family" music rather than "kids" music. Considering his upbringing, Chapin was destined for a life in the arts. He grew up in New York City's Greenwich Village and Brooklyn Heights in a family that encouraged all the children to develop their creative talents. The senior Chapin, Jim, was a jazz drummer who performed with renowned bandleaders Tommy Dorsey and Woody Herman. One of Tom's grandfathers was a painter, and the other was a philosopher. When he was 12, Tom and his two brothers, Steve and Harry, fell under the influence of the seminal folk group the Weavers. The Chapin kids formed their own folk trio, calling themselves the Chapins. They played nightclub gigs in New York for a number of years and recorded their first album, Chapin Music!, in 1966.