9789814779241

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Mascots: Performance and Fetishism in Sport Culture

Platform , Vol. 3, No. 1 Mascots: Performance and Fetishism in Sport Culture Mary C. Daily (Boston College) Sport culture is something of great interest to citizens ranging from sociology scholars 1 to sports fans. The performance rituals that accompany sport include victory dances, school songs, cheers, and mascots. As Rick Minter, a mascot historian writes, “We all care about the symbols, nicknames, and legends of our club – mascots make them real again. They are a bit of our club that we can reach out and touch” (7). If we accept Minter’s conceptualization, what is the theoretical foundation that supports these representations? They make us laugh, we enjoy their athleticism, and kids love them; however, their lineage and purpose runs far deeper than their presence in the arena. This paper argues that mascot performances represent fetishized aspects of sport culture, and specifically, that such rituals embody the ability to relate to and influence the providence of a chosen athletic team. Arguably, the success of college and professional sport teams rests on their ability to claim triumph, and mascot performances are an integral part of that process to those who believe in their power. While sports fans enjoy mascots for their physicality as furry caricatures that dance along the sidelines, their significance is founded on a supernatural power relationship. The performance of mascots perpetuates their fetishized status in sports ranging from high school soccer to professional football. In the discussion of fetishization, one must be forgiving of possible oversimplifications present in the summarizing of various theorists, as the paper’s 1 James Frey and Günter Lüschen outline both collegiate and professional athletics, exploring competition, reception, and cultural significance. -

World Cities Summit 2016

BETTER CITIES Your monthly update from the Centre for Liveable Cities Issue 67 July 2016 World Cities Summit 2016 The World Cities Summit 2016, co-organised by the Centre for Liveable Cities and the Urban Redevelopment Authority, attracted about 110 mayors and city leaders representing 103 cities from 63 countries and regions around the world to engage on issues of urban sustainability. Held from 10-14 July, the fifth edition of the World Cities Summit, together with Singapore International Water Week (SIWW) and CleanEnviro Summit Singapore (CESS), was attended by more than 21,000 visitors and participants including ministers, government officials, industry leaders and experts, academics, as well as representatives from international organisations. Themed ‘Liveable and Sustainable Cities: Innovative Cities of Opportunity’, this year’s Summit expanded its focus on how cities can leverage innovations to build smart cities. A key highlight of the expo was the ‘Towards a Smart and Sustainable Singapore’ pavilion, which showcased innovations from more than 16 Singapore government agencies designed to help serve citizens better. WCS 2016 also explored the strategy of co-creation and how cities can better engage their citizens to build more resilient cities beyond infrastructure alone. For the first time at WCS, the impact of softer aspects of a city like culture and heritage on urban planning and design was discussed at a dedicated track. The next World Cities Summit will be held from 8-12 July 2018 at the Sands Expo and Convention Centre, Singapore. Click here for the WCS 2016 press release. Enabling Technologies: A Prototype for Urban Planning By Zhou Yimin CLC is working with the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT) on an interactive urban planning tool that creates realistic simulations of planning decisions and allows planners to understand the implications for their city. -

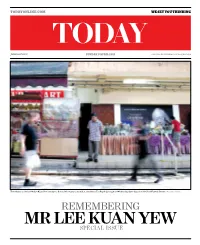

Lee Kuan Yew Continue to flow As Life Returns to Normal at a Market at Toa Payoh Lorong 8 on Wednesday, Three Days After the State Funeral Service

TODAYONLINE.COM WE SET YOU THINKING SUNDAY, 5 APRIL 2015 SPECIAL EDITION MCI (P) 088/09/2014 The tributes to the late Mr Lee Kuan Yew continue to flow as life returns to normal at a market at Toa Payoh Lorong 8 on Wednesday, three days after the State Funeral Service. PHOTO: WEE TECK HIAN REMEMBERING MR LEE KUAN YEW SPECIAL ISSUE 2 REMEMBERING LEE KUAN YEW Tribute cards for the late Mr Lee Kuan Yew by the PCF Sparkletots Preschool (Bukit Gombak Branch) teachers and students displayed at the Chua Chu Kang tribute centre. PHOTO: KOH MUI FONG COMMENTARY Where does Singapore go from here? died a few hours earlier, he said: “I am for some, more bearable. Servicemen the funeral of a loved one can tell you, CARL SKADIAN grieved beyond words at the passing of and other volunteers went about their the hardest part comes next, when the DEPUTY EDITOR Mr Lee Kuan Yew. I know that we all duties quietly, eiciently, even as oi- frenzy of activity that has kept the mind feel the same way.” cials worked to revise plans that had busy is over. I think the Prime Minister expected to be adjusted after their irst contact Alone, without the necessary and his past week, things have been, many Singaporeans to mourn the loss, with a grieving nation. fortifying distractions of a period of T how shall we say … diferent but even he must have been surprised Last Sunday, about 100,000 people mourning in the company of others, in Singapore. by just how many did. -

Mayors and City Leaders Will Discuss How to Build a High Trust City

MAYORS AND CITY LEADERS WILL DISCUSS HOW TO BUILD A HIGH TRUST CITY The 10th World Cities Summit (WCS) Mayors Forum and 6th Young Leaders Symposium will be held in Medellín, Colombia, from 10 to 12 July 2019. The city of Medellín was named the 2016 Lee Kuan Yew World City Prize Laureate and will host the event. The event will bring together over 200 participants from around the world, including mayors, city leaders, and senior leaders from the industry and international organisations, with representatives from all regions of the world. 2 Mr Lawrence Wong, Minister for National Development and Second Minister for Finance, Singapore will chair the Forum, and will deliver the opening and closing addresses on 11 and 12 July 2019. The host city will be represented by Mr Federico Gutiérrez, Mayor of Medellín City. Liveable and Sustainable Cities: Building a High Trust City 3 Themed "Liveable and Sustainable Cities: Building a High Trust City", the discussions at the WCS Mayors Forum and WCS Young Leaders Symposium will explore the latest innovations and good practices in city governance that help build confidence in cities’ societies and institutions, and how cities should plan for economic and environmental security in an age of unpredictable economic fluctuations and extreme weather events. 4 Notable attendees will include the Governor of Jakarta Anies Baswedan, Deputy Minister of Moscow City Government Ilya Kuzmin, Chairman of Muscat Municipality Mohsen Bin Mohammed Al-Sheikh and Mayor of Seoul Park Won-soon. Interactive sessions amongst participants will provide opportunities for in-depth discussions on these issues. The synopses of the Mayors Forum sessions are provided in Annex A. -

WORLD CITIES SUMMIT 9Th MAYORS FORUM

WORLD CITIES SUMMIT th 9 MAYORS FORUM “Liveable & Sustainable Cities: Embracing the Future through Innovation and Collaboration” 8 July 2018 WORLD CITIES SUMMIT 9TH MAYORS FORUM 2018 1 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY 124 Mayors and City Leaders participated in the 9th World Cities Summit Mayors Forum on 8 July 2018 in Singapore. Two pressing global needs topped the agenda of the 9th to streamline its streets to manage massive pedestrian the government, businesses and ordinary citizens, World Cities Summit Mayors Forum: Embracing disruptive flows. In Amman, these challenges are exacerbated would all welcome more space and flexibility to test innovation and financing infrastructure. Held in Singapore by circumstances such as the influx of refugees, new business models and float ideas to make city and attended by 124 mayors and city leaders from 119 mostly from Syria. The fourth industrial revolution is living more efficient and sustainable. Globally, there cities, the Forum explored how liveable cities could characterised by disruptive technologies that have is a renewed call to embrace innovation with fresh learn and adopt new technologies, and find more changed the way we live and work. Artificial intelligence. mindsets ready for experimentation and adaptation; to funding sources to finance infrastructure projects. Machine Learning. Internet of Things. Although reimagine the city as a living laboratory to try out new they offer new tools to increase our connectivity and ways to build a city. Are Cities Ready for the Fourth productivity, they will also displace old jobs, and even threaten upheaval of human relations. Industrial Revolution? Co-Creation is a Vital Keyword, More Than Ever The current pace and scale of urbanisation require all In today’s transformative landscape, cities must cities to be ready to embrace new technologies – even relook existing forms of governance, planning, For cities to nurture and embrace innovation, the role for cities where familiar problems like road congestion citizen involvement and the investment ecosystem. -

Examining the Changing Use of the Bear As a Symbol of Russia

UC Santa Barbara UC Santa Barbara Previously Published Works Title The “Forward Russia” Flag: Examining the Changing Use of the Bear as a Symbol of Russia Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/5xz8x2zc Journal Raven: A Journal of Vexillology, 19 ISSN 1071-0043 Author Platoff, Anne M. Publication Date 2012 License https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/ 4.0 Peer reviewed eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California The “Forward Russia” Flag 99 The “Forward Russia” Flag: Examining the Changing Use of the Bear as a Symbol of Russia Anne M. Platoff Introduction Viewers of international sporting events have become accustomed to seeing informal sporting flags waved by citizens of various countries. The most famil- iar of these flags, of course, are the “Boxing Kangaroo” flag used to represent Australia and the “Fighting Kiwi” flag used by fans from New Zealand. Both of these flags have become common at the Olympic Games when athletes from those nations compete. Recently a new flag of this type has been displayed at international soccer matches and the 2010 Vancouver Winter Olympics. Unlike the Kangaroo and Kiwi flags, this new flag has been constructed using a defaced national flag, the Russian tricolor flag of white, blue, and red horizontal stripes, readopted as the flag of the Russian Federation after the breakup of the Soviet Union. A number of variations of the flag design have been used, but all of them contain two elements: the Russian text Vperëd Rossiia, which means “Forward Russia”, and a bear which appears to be break- ing its way out of the flag. -

Urban Solutions and Forge New • 48: Guocoland Singapore • 97(1): Hewlett Packard Enterprise • 51: John Liddle Photography • 97(2): Edimax Partnerships

Innovation & Collaboration ISSUE 13 • JUL 2018 INNOVATION & COLLABORATION INNOVATION The Centre for Liveable Cities seeks to distil, create and share knowledge on liveable and sustainable cities. Our work spans four main areas, namely Research, Capability Development, Knowledge Platforms and Advisory. Through these efforts, we aim to inspire and give urban leaders and practitioners the knowledge and support they need to make cities more liveable and sustainable. Discover what CLC does on our digital channels. EXPLORE CONNECT IMMERSE www Interview Ranil Wickremesinghe Vivian Balakrishnan clc.gov.sg CLCsg CLC01SG Opinion Geoffrey West Essay SPECIAL ISSUE Maimunah Mohd Sharif Yuting Xu & Yimin Zhou Mina Zhan & Michael Koh ISSUE 13 • JUL 2018 City Focus Seoul Case Study Singapore London Contact Amaravati [email protected] A bi-annual magazine published by is a bi-annual magazine published by the Centre for Liveable Cities. It aims to equip and inspire city leaders and allied professionals to make cities more liveable and sustainable. THANK YOU Set up in 2008 by the Ministry of National Development and the Ministry of the Environment and Water Resources, the Centre for Liveable Cities (CLC) has as its mission “to distil, create and share knowledge on liveable and sustainable cities”. CLC’s work spans four main areas— Research, Capability Development, Knowledge Platforms, and Advisory. Through these activities, CLC hopes to provide urban leaders and FOR BEING A PART OF practitioners with the knowledge and support needed to make our cities better. www.clc.gov.sg CLC is a division of JUL 2018 ISSUE 13 • Image Credits Advisory Panel Dr Liu Thai Ker (Chairman) • 4: Sri Lanka Government • 62: Seoul Metropolitan Government • 6(1): hecke61 / Shutterstock • 63: Son/Metro 손진영기자 Chairman • 6(2): Sergii Rudiuk/ Shutterstock • 64: Maxim Schulz - www.mediaserver.hamburg. -

Up for the Fight: Success and Shortcomings in the Movement to Eliminate Native American Sports Mascots and Logos in American Colleges and Universities, 1970-1978

1 Up For The Fight Up for the Fight: Success and Shortcomings in the Movement to Eliminate Native American Sports Mascots and Logos in American Colleges and Universities, 1970-1978. Eugenia Pacitti (Monash University) Abstract: Following the prominence of African American civil rights activism in the 1960s, the 1970s saw several important protests by the Native American community, commonly known as the “Red Power” movement. This article examines a part of this movement that has not received widespread attention: the effort between 1970 and 1978 to eliminate Native American sports mascots and logos from colleges and universities in the United States. Although there were significant achievements made by the activists involved, who considered these representations to be demeaning and false, there are still over one thousand such mascots and logos active today. This article focuses on five major US universities and colleges, and considers the successes and shortcomings of the movement to eliminate Native American mascots at each of them. These reasons include a lack of unity amongst Native American students, a lack of support from the wider Native American community, strong opposition from college and university alumni, and an inability to gain the support of local or national politicians or Native American activists for the cause. The unique nature of sports such as baseball, basketball and ice hockey within American college and university culture is also taken into consideration. This article adds to discussions about racial appropriation within American sporting culture, and considers the movement to eliminate Native American sports mascots and logos within a narrative of the “Red Power” movement, positing as to why the movement was only partially realised. -

Innovative Cities of Opportunity

INNOVATIVE CITIES OF OPPORTUNITY (A report on World Cities Summit 2016) 2 A SUMMIT OF SIGNIFICANCE 4 DRIVING CHANGE THROUGH THOUGHT LEADERSHIP 6 INNOVATIVE CITIES OF OPPORTUNITY 16 DEMONSTRATE, EXHIBIT, SHOWCASE 18 COLLABORATE AND ENGAGE 20 ATTRACTING INTERNATIONAL COVERAGE 22 ABOUT THE ORGANISERS A SUMMIT OF SIGNIFICANCE I found the experience It was a meaningful My time spent at the World informative and enjoyable. It occasion to deliberate Cities Summit was incredibly was a great opportunity to share about how to make cities valuable. The Summit was a Wellington’s success stories more liveable and how to fantastic opportunity to learn with other Mayors and Summit improve the quality of life from other global cities and to attendees, and learn about the of citizens build relationships with other approach other cities around the world are taking to planning, Park Won-soon Martin Haese city leaders Celia Wade-Brown Mayor, Seoul Lord Mayor Mayor, Wellington, governance, resilience and Metropolitan City, South Korea Adelaide, Australia New Zealand innovation YOUNG The biennial World Cities Summit is an exclusive platform LEADERS for government leaders and industry experts to address liveable and sustainable city challenges, share integrated urban solutions, and forge new partnerships. It is a global The World Cities Summit Mayors Forum is an annual by- The Lee Kuan Yew World City Prize is a biennial The World Cities Summit Young Leaders is a select group of platform to explore how cities can better govern and build up invitation only global event for city leaders to discuss pressing international award that honours outstanding achievements change-makers from diverse sectors who shape the global resilience through policy, technology and social innovations. -

Factsheet Worldcitiessummit2012

Factsheet World Cities Summit 2012 1 to 4 July 2012, Sands Expo & Convention Center, Marina Bay Sands, Singapore www.worldcities.com.sg About the World Cities Summit (WCS) Held from 1 to 4 July 2012, the World Cities Summit is a biennial global event for world leaders and experts to exchange new ideas on liveable and sustainable urban solutions, explore the latest technologies and forge new business partnerships. Based on the theme of “Liveable And Sustainable Cities – Integrated Urban Solutions”, the third edition of the Summit is expected to share new insights and trends on urbanisation challenges around the world. Since it started in 2008, this biennial high-level global Summit has been attracting top government and industry leaders from around the world. The third run this year is timely given the urgent need for cities to step up their efforts to address mounting urbanisation challenges. The Summit offers a platform for dialogue and learning through sharing of best practices, which offer new insights and perspectives to addressing cities’ unique problems and challenges. The World Cities Summit is co-organised by the Centre for Liveable Cities and the Urban Redevelopment Authority. Refer to Annex A for an overview of the World Cities Summit programme. Why focus on integrated solutions Touching on a new direction for cities of the future, the Summit’s theme is “Liveable and Sustainable Cities – Integrated Urban Solutions”. Explaining the focus on an integrated approach, Mr Khoo Teng Chye, Executive Director of the Centre for Liveable Cities said: “By 2050, 70% of the world’s population will be living in cities. -

Building for Tomorrow

Thai cave rescue Interview with Moon Jae-in Summit city, Singapore MCI(P) 096/08/2017 FebruaryAugust – September- MCI(P)March 096/08/2017 2018 2018 INDEPENDENT • INSIDER • INSIGHTS ON ASIA Smart Cities: Building for Tomorrow A global push to build smart cities is on with policy makers and shapers scouting for the best technology solutions to allow people to enjoy their living and working spaces. Thai cave rescue Interview with Moon Jae-in Summit city, Singapore MCI(P) 096/08/2017 FebruaryAugust – September- MCI(P)March 096/08/2017 2018 2018 INDEPENDENT • INSIDER • INSIGHTS ON ASIA Contents Smart Cities: Building for Tomorrow A global push to build smart cities is on with policy makers and shapers scouting for the best technology solutions to allow people to enjoy their living and working spaces. 2 Getting smarter for the future 5 Rise of Asian Smart Cities Asia Report August – September 2018 CHINA: Yinchuan leads the way in using tech to improve daily life JAPAN: Small but smart cities woo business and young talent Warren Fernandez Editor-in-Chief, The Straits Times & SPH’s English, Malay and 8 Smart City Mayors: Mayor, West Java governor... Indonesia’s Tamil Media (EMTM) Group president in 2024? Sumiko Tan 11 A network of smart cities Managing Editor, EMTM & Executive Editor, The Straits Times 13 Cooling Singapore project comes up with new ways Tan Ooi Boon to beat the heat Senior Vice-President (Business Development), EMTM 15 Cheers! A special beer to mark a special anniversary Paul Jacob Associate Editor, The Straits Times 16 Thailand -

Olympic Summer Games Mascots from Munich 1972 to Rio 2016 Reference Document

Olympic Summer Games Mascots from Munich 1972 to Rio 2016 Reference document 09.02.2017 Olympic Summer Games Mascots from Munich 1972 to Rio 2016 CONTENT Introduction 3 Munich 1972 4 Montreal 1976 6 Moscow 1980 8 Los Angeles 1984 10 Seoul 1988 12 Barcelona 1992 14 Atlanta 1996 16 Sydney 2000 18 Athens 2004 20 Beijing 2008 22 London 2012 24 Rio 2016 26 Credits 28 The Olympic Studies Centre www.olympic.org/studies [email protected] 2 Olympic Summer Games Mascots from Munich 1972 to Rio 2016 INTRODUCTION The word mascot is derived from the Provencal and appeared in French dictionaries at the end of the 19th century. “It caught on following the triumphant performance of Mrs Grizier- Montbazon in an operetta called La Mascotte, set to music by Edmond Audran in 1880. The singer’s success prompted jewellers to produce a bracelet charm representing the artist in the costume pertaining to her role. The jewel was an immediate success. The mascot, which, in its Provencal form, was thought to bring good or bad luck, thus joined the category of lucky charms.” 1 The first Olympic mascot – which was not official – was named “Schuss” and was created for the Olympic Winter Games Grenoble 1968. A little man on skis, half-way between an object and a person, it was the first manifestation of a long line of mascots which would not stop. It was not until the Olympic Summer Games Munich 1972 that the first official Olympic mascot was created. Since then, mascots have become the most popular and memorable ambassadors of the Olympic Games.