Left Neglected

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Normal Heart

THE NORMAL HEART Written By Larry Kramer Final Shooting Script RYAN MURPHY TELEVISION © 2013 Home Box Office, Inc. ALL RIGHTS RESERVED. No portion of this script may be performed, published, reproduced, sold or distributed by any means or quoted or published in any medium, including on any website, without the prior written consent of Home Box Office. Distribution or disclosure of this material to unauthorized persons is prohibited. Disposal of this script copy does not alter any of the restrictions previously set forth. 1 EXT. APPROACHING FIRE ISLAND PINES. DAY 1 Masses of beautiful men come towards the camera. The dock is full and the boat is packed as it disgorges more beautiful young men. NED WEEKS, 40, with his dog Sam, prepares to disembark. He suddenly puts down his bag and pulls off his shirt. He wears a tank-top. 2 EXT. HARBOR AT FIRE ISLAND PINES. DAY 2 Ned is the last to disembark. Sam pulls him forward to the crowd of waiting men, now coming even closer. Ned suddenly puts down his bag and puts his shirt back on. CRAIG, 20s and endearing, greets him; they hug. NED How you doing, pumpkin? CRAIG We're doing great. 3 EXT. BRUCE NILES'S HOUSE. FIRE ISLAND PINES. DAY 3 TIGHT on a razor shaving a chiseled chest. Two HANDSOME guys in their 20s -- NICK and NINO -- are on the deck by a pool, shaving their pecs. They are taking this very seriously. Ned and Craig walk up, observe this. Craig laughs. CRAIG What are you guys doing? NINO Hairy is out. -

''What Lips These Lips Have Kissed'': Refiguring the Politics of Queer Public Kissing

Communication and Critical/Cultural Studies Vol. 3, No. 1, March 2006, pp. 1Á/26 ‘‘What Lips These Lips Have Kissed’’: Refiguring the Politics of Queer Public Kissing Charles E. Morris III & John M. Sloop In this essay, we argue that man-on-man kissing, and its representations, have been insufficiently mobilized within apolitical, incremental, and assimilationist pro-gay logics of visibility. In response, we call for a perspective that understands man-on-man kissing as a political imperative and kairotic. After a critical analysis of man-on-man kissing’s relation to such politics, we discuss how it can be utilized as a juggernaut in a broader project of queer world making, and investigate ideological, political, and economic barriers to the creation of this queer kissing ‘‘visual mass.’’ We conclude with relevant implications regarding same-sex kissing and the politics of visible pleasure. Keywords: Same-Sex Kissing; Queer Politics; Public Sex; Gay Representation In general, one may pronounce kissing dangerous. A spark of fire has often been struck out of the collision of lips that has blown up the whole magazine of 1 virtue.*/Anonymous, 1803 Kissing, in certain figurations, has lost none of its hot promise since our epigraph was penned two centuries ago. Its ongoing transformative combustion may be witnessed in two extraordinarily divergent perspectives on its cultural representation and political implications. In 2001, queer filmmaker Bruce LaBruce offered in Toronto’s Eye Weekly a noteworthy rave of the sophomoric buddy film Dude, Where’s My Car? One scene in particular inspired LaBruce, in which we find our stoned protagonists Jesse (Ashton Kutcher) and Chester (Seann William Scott) idling at a stoplight next to superhunk Fabio and his equally alluring female passenger. -

Song Catalogue February 2020 Artist Title 2 States Mast Magan 2 States Locha E Ulfat 2 Unlimited No Limit 2Pac Dear Mama 2Pac Changes 2Pac & Notorious B.I.G

Song Catalogue February 2020 Artist Title 2 States Mast Magan 2 States Locha_E_Ulfat 2 Unlimited No Limit 2Pac Dear Mama 2Pac Changes 2Pac & Notorious B.I.G. Runnin' (Trying To Live) 2Pac Feat. Dr. Dre California Love 3 Doors Down Kryptonite 3Oh!3 Feat. Katy Perry Starstrukk 3T Anything 4 Non Blondes What's Up 5 Seconds of Summer Youngblood 5 Seconds of Summer She's Kinda Hot 5 Seconds of Summer She Looks So Perfect 5 Seconds of Summer Hey Everybody 5 Seconds of Summer Good Girls 5 Seconds of Summer Girls Talk Boys 5 Seconds of Summer Don't Stop 5 Seconds of Summer Amnesia 5 Seconds of Summer (Feat. Julia Michaels) Lie to Me 5ive When The Lights Go Out 5ive We Will Rock You 5ive Let's Dance 5ive Keep On Movin' 5ive If Ya Getting Down 5ive Got The Feelin' 5ive Everybody Get Up 6LACK Feat. J Cole Pretty Little Fears 7Б Молодые ветра 10cc The Things We Do For Love 10cc Rubber Bullets 10cc I'm Not In Love 10cc I'm Mandy Fly Me 10cc Dreadlock Holiday 10cc Donna 30 Seconds To Mars The Kill 30 Seconds To Mars Rescue Me 30 Seconds To Mars Kings And Queens 30 Seconds To Mars From Yesterday 50 Cent Just A Lil Bit 50 Cent In Da Club 50 Cent Candy Shop 50 Cent Feat. Eminem & Adam Levine My Life 50 Cent Feat. Snoop Dogg and Young Jeezy Major Distribution 101 Dalmatians (Disney) Cruella De Vil 883 Nord Sud Ovest Est 911 A Little Bit More 1910 Fruitgum Company Simon Says 1927 If I Could "Weird Al" Yankovic Men In Brown "Weird Al" Yankovic Ebay "Weird Al" Yankovic Canadian Idiot A Bugs Life The Time Of Your Life A Chorus Line (Musical) What I Did For Love A Chorus Line (Musical) One A Chorus Line (Musical) Nothing A Goofy Movie After Today A Great Big World Feat. -

Cutbank 84 Article 1

CutBank Volume 1 Issue 84 CutBank 84 Article 1 Spring 2016 CutBank 84 Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.umt.edu/cutbank Part of the Creative Writing Commons Let us know how access to this document benefits ou.y Recommended Citation (2016) "CutBank 84," CutBank: Vol. 1 : Iss. 84 , Article 1. Available at: https://scholarworks.umt.edu/cutbank/vol1/iss84/1 This Full Volume is brought to you for free and open access by ScholarWorks at University of Montana. It has been accepted for inclusion in CutBank by an authorized editor of ScholarWorks at University of Montana. For more information, please contact [email protected]. CutBank | 84 ISBN 9781939717092 CutBank 84 9 781939 717092 CutBank 84 CutBank is published biannually at the University of Montana by graduate students in the Creative Writing Program. Publication is funded and supported by the As- sociated Students of Montana, the Pleiades Foundation, the Second Wind Reading Series, Humanities Montana, Tim O’Leary, Michelle Cardinal, William Kittredge, Annick Smith, Truman Capote Literary Trust, Sponsors of the Fall Writer’s Opus, the Department of English, the Creative Writing Program, Kevin Canty, Judy Blunt, Karin Schalm, Michael Fitzgerald & Submittable, and our readers & donors. Subscriptions are $15 per year + $3 for subscriptions outside of North America. Make checks payable to CutBank or shop online at www.cutbankonline.org/subscribe. Our reading period is September 15 - February 1. Complete submission guidelines are available online. No portion of CutBank may be reproduced without permission. All rights reserved. All correspondence to: CutBank English Department, LA 133 University of Montana Missoula, MT 59812 Printed by Sheridan Press. -

Pence, DOD Leaders Remember 9/11 by Terri Moon Cronk at the Pentagon 9/11 Memorial Observance Tuesday

Vol. 76, No. 37 Sept. 14, 2018 Striving to be best of best Photo by Scott Prater Staff Sgt. Justin Templeton, 52nd Brigade Engineer Battalion, 2nd Infantry Brigade command team’s security detail. The course’s planning began last summer and is now Combat Team, 4th Infantry Division, prepares to dismount an obstacle at Fort Carson’s a complete obstacle course, set up in a loop. Each obstacle was constructed using newest obstacle course Monday. Templeton was among several Soldier candidates treated lumber and steel and features a pea-gravel soft ground area, surrounded by who challenged the course in hopes of earning a spot on the 4th Infantry Division railroad ties. See story on pages 18-19. Pence, DOD leaders remember 9/11 By Terri Moon Cronk at the Pentagon 9/11 Memorial observance Tuesday. Paul J. Selva hosted Pence for the annual remembrance DOD News, Defense Media Activity They failed, he said. for families and friends of those who fell at the Pentagon. “The American people showed on that day and Seventeen years ago, terrorists flew American WASHINGTON — The terrorists who attacked the every day since, we will not be intimidated,” the vice Airlines Flight 77 into the Pentagon. One hundred U.S. on Sept. 11, 2001, sought not just to take the lives president said. “Our spirit cannot be broken.” eighty nine people perished — 125 service members of U.S. citizens and crumble buildings; they hoped to Defense Secretary James N. Mattis and Vice break America’s spirit, Vice President Mike Pence said Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff Air Force Gen. -

Triple J Hottest 100 2011 | Voting Lists | Sorted by Artist Name Page 1 VOTING OPENS December 14 2011 | Triplej.Net.Au

360 - Boys Like You {Ft. Gossling} Anna Lunoe & Wax Motif - Love Ting 360 - Child Antlers, The - I Don't Want Love 360 - Falling & Flying Architecture In Helsinki - Break My Stride {Like A Version} 360 - I'm OK Architecture In Helsinki - Contact High 360 - Killer Architecture In Helsinki - Denial Style 360 - Meant To Do Architecture In Helsinki - Desert Island 360 - Throw It Away {Ft. Josh Pyke} Architecture In Helsinki - Escapee [Me] - Naked Architecture In Helsinki - I Know Deep Down 2 Bears, The - Work Architecture In Helsinki - Sleep Talkin' 2 Bears, The - Bear Hug Architecture In Helsinki - W.O.W. A.A. Bondy - The Heart Is Willing Architecture In Helsinki - Yr Go To Abbe May - Design Desire Arctic Monkeys - Black Treacle Abbe May - Taurus Chorus Arctic Monkeys - Don't Sit Down Cause I've Moved Your About Group - You're No Good Chair Active Child - Hanging On Arctic Monkeys - Library Pictures Adalita - Burning Up {Like A Version} Arctic Monkeys - She's Thunderstorms Adalita - Hot Air Arctic Monkeys - The Hellcat Spangled Shalalala Adalita - The Repairer Argentina - Bad Kids Adrian Lux - Boy {Ft. Rebecca & Fiona} Art Brut - Lost Weekend Adults, The - Nothing To Lose Art Vs Science - A.I.M. Fire! Afrojack & Steve Aoki - No Beef {Ft. Miss Palmer} Art Vs Science - Bumblebee Agnes Obel - Riverside Art Vs Science - Harder, Better, Faster, Stronger {Like A Albert Salt - Fear & Loathing Version} Aleks And The Ramps - Middle Aged Unicorn On Beach With Art Vs Science - Higher Sunset Art Vs Science - Meteor (I Feel Fine) Alex Burnett - Shivers {Straight To You: triple j's tribute To Art Vs Science - New World Order Nick Cave} Art Vs Science - Rain Dance Alex Metric - End Of The World {Ft. -

Open 4D 2020

Open 4D 2020 Horse Age, Color, Sex Owner / Rider Sire # Dam, Dam's Sire Breeder 1st Go Owner Stallion Breeder Carry to Open toCarry Open Incentive Youth Tres Movidas Tom Jacobs 2012 Sorrel Mare Thomas Ford Jacobs Pritchett, CO Tres Seis Pritchett, CO Hallie Hanssen 171 Sheza Blazin Move, Blazin Jetolena 16.771 1D-1 $ 11,688 $ 1,375 $ 688 Slicks Lil Amigo Deanna Pietsch Jason Martin & Charlie 2014 Bay Gelding Sarasota, FL Cole Slick By Design Sabra O'Quinn Pilot Point, TX 193 Bough Chicka Wowwow, Bully Bullion 16.864 1D-2 $ 7,948 $ 935 $ 468 Miss Eedie Stinson Lindsay Schulz 2010 Sorrel Mare Blair & Dalarie Philippi Moses Lake, WA Eddie Stinson Boardman, OR Lindsay Schulz 262 Judge Two Cash, Judge Cash 16.886 1D-3 $ 6,078 $ 715 $ 358 Feel The Sting * Charlie Cole/Jason Martin 2013 Chestnut Stallion Mel Potter/ Sherry Cervi Pilot Point, TX Dash Ta Fame Marana, AZ Ryann Pedone 11 MP Meter My Hay, PC Frenchmans Hay Day 16.943 1D-4 $ 4,301 $ 506 $ 253 Too Slick To Wait Calvin & Becky Rhodes 2015 Chestnut Mare Calvin & Becky Rhodes Pilot Point, TX Slick By Design Pilot Point, TX Tyler Crosby 64 Waiting For You, Sorrel Doc Eddie 16.972 1D-5 $ 3,506 $ 413 $ 206 Manny Dot Com McColee Land & Livestock 2009 Bay Gelding Melvin D Griffeth Spanish Fork, UT PC Redwood Manny Rexburg, ID Jade Rindlisbacher 82 Speed Dot Com, Sixarun 16.975 1D-6 $ 2,712 $ 319 $ 160 Slick N Black Cayla Melby Small 2014 Black Mare Jane &/or Ryan Melby Wilson, OK Slick By Design Willson, OK Cayla Small 152 RC Back In Black, Ninety Nine Goldmine 17.003 1D-7 $ 2,151 $ 253 $ 127 Briscos Bug Erica Blankeney 2014 Sorrel Gelding Elan Brooks Williamson, GA Shawne Bug Leo Eastanolle, GA Craig Brooks 365 Briscos Dream Gal, Briscos Country Jr 17.066 1D-8 $ 1,683 $ 198 $ 99 VF Cream Rises Ademir Jose Rorato 2016 Sorrel Mare Victory Farms Lexington, OK Eddie Stinson Ada, OK Kelsey Treharne 13 Curiocity Corners, Silver Lucky Buck 17.067 1D-9 $ 1,403 $ 165 $ 83 KN Snap Back Julien Veileux 2016 Mare Stephen Nicholes St. -

MAY/JUN 2020 PORSCHE PROFILE 1 2 PORSCHE PROFILE MAY/JUN 2020 33 Tour to Linger Lodge

MAY/JUN 2020 PORSCHE PROFILE 1 2 PORSCHE PROFILE MAY/JUN 2020 33 Tour to Linger Lodge FEATURES The Saga of 356 #119205 . 20 EVENTS Breakfast with Porsches . 27 Tire Rack Street Survival . 28 Linger Lodge Tour . 33 20 27 PORSCHE INTEREST Charity—Ready for Life . 30 Taycan Intro at Reeves . 39 DEPARTMENTS The President’s Message . 5 Social Ramblings . 7 Schedule of Events . 9 Saga of 356 The Membership Starting Line . 11 #119205 The Way It Was . 13 Photo of the Month . 15 Tech Notes . 17 Rally Meister . 19 28 Business Card Corner . 43 The Last Turn . 45 Marketplace . 46 CONTRIBUTORS: ON THE COVER - Gerry Curt’s photo of his Gerry Curts, William Caldwell, Tire Rack Street Survival Course 1962 356 Coupe. See page 20 for all of the John Sabatini, Kathy Rossiter . details and more photos. MAY/JUN 2020 PORSCHE PROFILE 3 Suncoast Porsche Club of America Board of Directors OFFICERS President Past President Vice President Secretary Treasurer Denise Remus John Vita John Sabatini Daniela Boesshenz Paul Auger 727-215-7452 941-920-6698 813-493-6359 727-365-2219 410-984-3416 president@suncoastpca org. johnrvita@gmail com. vp@suncoastpca org. secretary@suncoastpca org. treasurer@suncoastpca org. ELECTED DIRECTORS BOARD MEMBERS AT LARGE Social Safety Rally Master Member at Large Member at Large Ed Rossiter Dave White Jim Hoey Pedro Bonilla Brian West 317-670-5207 727-709-0822 941-323-5184 954-385-0330 813-203-9869 social@suncoastpca org. dewyacht69@gmail com. rallymaster@suncoastpca org. pedro@pedrosgarage com. bwfst84@gmail com. PRESIDENT APPOINTED Webmaster . Paul Bienick - 941-544-2775 admin@suncoastpca org. -

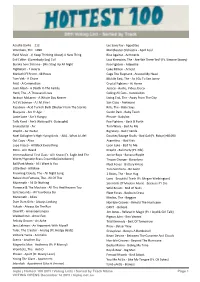

Triple J Hottest 100 2011 | Voting Lists | Sorted by Track Name Page 1 VOTING OPENS December 14 2011 | Triplej.Net.Au

Azealia Banks - 212 Les Savy Fav - Appetites Wombats, The - 1996 Manchester Orchestra - April Fool Field Music - (I Keep Thinking About) A New Thing Rise Against - Architects Evil Eddie - (Somebody Say) Evil Last Kinection, The - Are We There Yet? {Ft. Simone Stacey} Buraka Som Sistema - (We Stay) Up All Night Foo Fighters - Arlandria Digitalism - 2 Hearts Luke Million - Arnold Mariachi El Bronx - 48 Roses Cage The Elephant - Around My Head Tom Vek - A Chore Middle East, The - As I Go To See Janey Feist - A Commotion Crystal Fighters - At Home Juan Alban - A Death In The Family Justice - Audio, Video, Disco Herd, The - A Thousand Lives Calling All Cars - Autobiotics Jackson McLaren - A Whole Day Nearer Living End, The - Away From The City Art Vs Science - A.I.M. Fire! San Cisco - Awkward Kasabian - Acid Turkish Bath (Shelter From The Storm) Kills, The - Baby Says Bluejuice - Act Yr Age Caitlin Park - Baby Teeth Lanie Lane - Ain't Hungry Phrase - Babylon Talib Kweli - Ain't Waiting {Ft. Outasight} Foo Fighters - Back & Forth Snakadaktal - Air Tom Waits - Bad As Me Drapht - Air Guitar Big Scary - Bad Friends Noel Gallagher's High Flying Birds - AKA…What A Life! Douster/Savage Skulls - Bad Gal {Ft. Robyn}+B1090 Cut Copy - Alisa Argentina - Bad Kids Lupe Fiasco - All Black Everything Loon Lake - Bad To Me Mitzi - All I Heard Drapht - Bali Party {Ft. Nfa} Intermashional First Class - All I Know {Ft. Eagle And The Junior Boys - Banana Ripple Worm/Hypnotic Brass Ensemble/Juiceboxxx} Tinpan Orange - Barcelona Ball Park Music - All I Want Is You Fleet Foxes - Battery Kinzie Little Red - All Mine Tara Simmons - Be Gone Frowning Clouds, The - All Night Long 2 Bears, The - Bear Hug Naked And Famous, The - All Of This Lanu - Beautiful Trash {Ft. -

The Tenth Muse

The Tenth Muse Science Park High School Literary Magazine 2012 -- 2013 The Tenth Muse Some glory in their birth, some in their skill, Some in their wealth, some in their body's force, Some in their garments though new-fangled ill; Some in their hawks and hounds, some in their horse.” Shakespeare, Sonnet 91 Advisor Mr. Townsend Student Editors Niekelle Bloomfield-Hunter Christian Mendonça Daniela Fonseca Ashanti Hargrove The Tenth Muse is dedicated to Niekelle Bloomfield-Hunter, Christian Mendonça, Daniela Fonseca, and Ashanti Hargrove. Table of Contents Title Author Page(s) Sweet Deception Daniela Fonseca 1 Stained Perception Christian Mendonça 2 Individual Discovery Carla Silva 3 Awaiting Rose Rykeea Lowe 4 Life Everlasting Paloma Perroni 5 Life’s Reality Nadirah Lassiter 6 Winter Karina Zeron 7 The Field of Life Dajuan Burgess 8 Conflicted Muse Ashanti Hargrove 9 365 Aliyah Reynolds 10 Sparked Daniel Pruitt 11 Cherishing Life Cristina Cabral 12 Recognizing Imperfection Monet Jackson 13 Night Terrors Niekelle Bloomfield-Hunter 14 Like Scarlet Rain Darius Francois 15 Heartless Harry Morera 16 Sonnet 89 Adriana Dias 17 An Oyster’s Gift Cristina Cabral 18 - 20 Finding Freedom Carla Silva 21 - 25 Trouble’s Milkmaid Christian Mendonça 26 - 29 Mona Lisa Ashanti Hargrove 30 - 33 Sounds of Hope Rykeea Lowe 34 - 35 The Storm Rykeea Lowe 36 - 39 Mutiara Aliyah Reynolds 40 - 41 Pearl Harbor’s Love Story Monet Jackson 42 - 44 Les Superstitieux Niekelle Bloomfield-Hunter 45 - 46 Patriarchal Struggle in The Metamorphosis Lucas Schraier 47 - 48 Sweet Deception by Daniela Fonseca Green eyes to compliment his cunning smile, A cheery laugh to captivate your heart, You should beware of his uncommon style, His love is dangerous; you should be smart. -

The Gilded Owl

May 14, 2012 Design Posted by Andy Cristina Grajales Leave a comment Cristina Grajales Zaha Hadid / Liquid Glacial Bjorn Wiinblad The Chairs of Chiavari My Design Architecture Gio Ponti / Parco dei Principi Sorrento Villa Necchi Campiglio Milan Tadao Ando / The Modern Fort Worth Louis Kahn / Kimbell Art Museum Art Emma Bennett Stephen Appleby-Barr Music Rebel Rebel Records Top 5 Lou Doillon / I.C.U. Rebel Rebel Records Top 5 Lana Del Rey covers Kasabian’s “Goodbye Kiss” Lana Del Rey / Blue Jeans Rebel Rebel Records Top 5 Fashion Gilded Shoes for Spring Twitter Facebook Andy Goldsborough Interior Design About The Gilded Owl Cristina Grajales is the most passionate design enthusiast you will ever meet! She founded her eponymous gallery in January of 2001 and has since become a true visionary for what is both relevant and beautiful in the realm of creative types all over the world. When she left DeLorenzo Gallery and started her new venture she set out to be a “decorative arts advisor” sensing that there was something missing from the design world. converted by Web2PDFConvert.com Cristina's fantastic current show New York, New York Sam Baron, Bouquet de Tables Christophe Come table in iron with moongold leaf, glass roundrels and white gold leaf converted by Web2PDFConvert.com Christophe Come Exhibition at Duke & Duke Gallery Architect and designer Jean Prouve’s daughter, Simone Prouve, was the first textile designer Cristina was seduced by and began to represent. Grajales says she has to be “completely in love, be completely seduced” by an artists work to show them in the gallery. -

To Search This List, Hit CTRL+F to "Find" Any Song Or Artist Song Artist

To Search this list, hit CTRL+F to "Find" any song or artist Song Artist Length Peaches & Cream 112 3:13 U Already Know 112 3:18 All Mixed Up 311 3:00 Amber 311 3:27 Come Original 311 3:43 Love Song 311 3:29 Work 1,2,3 3:39 Dinosaurs 16bit 5:00 No Lie Featuring Drake 2 Chainz 3:58 2 Live Blues 2 Live Crew 5:15 Bad A.. B...h 2 Live Crew 4:04 Break It on Down 2 Live Crew 4:00 C'mon Babe 2 Live Crew 4:44 Coolin' 2 Live Crew 5:03 D.K. Almighty 2 Live Crew 4:53 Dirty Nursery Rhymes 2 Live Crew 3:08 Fraternity Record 2 Live Crew 4:47 Get Loose Now 2 Live Crew 4:36 Hoochie Mama 2 Live Crew 3:01 If You Believe in Having Sex 2 Live Crew 3:52 Me So Horny 2 Live Crew 4:36 Mega Mixx III 2 Live Crew 5:45 My Seven Bizzos 2 Live Crew 4:19 Put Her in the Buck 2 Live Crew 3:57 Reggae Joint 2 Live Crew 4:14 The F--k Shop 2 Live Crew 3:25 Tootsie Roll 2 Live Crew 4:16 Get Ready For This 2 Unlimited 3:43 Smooth Criminal 2CELLOS (Sulic & Hauser) 4:06 Baby Don't Cry 2Pac 4:22 California Love 2Pac 4:01 Changes 2Pac 4:29 Dear Mama 2Pac 4:40 I Ain't Mad At Cha 2Pac 4:54 Life Goes On 2Pac 5:03 Thug Passion 2Pac 5:08 Troublesome '96 2Pac 4:37 Until The End Of Time 2Pac 4:27 To Search this list, hit CTRL+F to "Find" any song or artist Ghetto Gospel 2Pac Feat.