The Psalms in Rastafari Reggae

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Dub Issue 15 August2017

AIRWAVES DUB GREEN FUTURES FESTIVAL RADIO + TuneIn Radio Thurs - 9-late - Cornerstone feat.Baps www.greenfuturesfestivals.org.uk/www.kingstongreenradi o.org.uk DESTINY RADIO 105.1FM www.destinyradio.uk FIRST WEDNESDAY of each month – 8-10pm – RIDDIM SHOW feat. Leo B. Strictly roots. Sat – 10-1am – Cornerstone feat.Baps Sun – 4-6pm – Sir Sambo Sound feat. King Lloyd, DJ Elvis and Jeni Dami Sun – 10-1am – DestaNation feat. Ras Hugo and Jah Sticks. Strictly roots. Wed – 10-midnight – Sir Sambo Sound NATURAL VIBEZ RADIO.COM Daddy Mark sessions Mon – 10-midnight Sun – 9-midday. Strictly roots. LOVERS ROCK RADIO.COM Mon - 10-midnight – Angela Grant aka Empress Vibez. Roots Reggae as well as lo Editorial Dub Dear Reader First comments, especially of gratitude, must go to Danny B of Soundworks and Nick Lokko of DAT Sound. First salute must go to them. When you read inside, you'll see why. May their days overflow with blessings. This will be the first issue available only online. But for those that want hard copies, contact Parchment Printers: £1 a copy! We've done well to have issued fourteen in hard copy, when you think that Fire! (of the Harlem Renaissance), Legitime Defense and Pan African were one issue publications - and Revue du Monde Noir was issued six times. We're lucky to have what they didn't have – the online link. So I salute again the support we have from Sista Mariana at Rastaites and Marco Fregnan of Reggaediscography. Another salute also to Ali Zion, for taking The Dub to Aylesbury (five venues) - and here, there and everywhere she goes. -

{PDF} So Much Things to Say the Oral History of Bob Marley 1St Edition Ebook, Epub

SO MUCH THINGS TO SAY THE ORAL HISTORY OF BOB MARLEY 1ST EDITION PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Roger Steffens | 9780393058451 | | | | | So Much Things to Say The Oral History of Bob Marley 1st edition PDF Book Return to Book Page. Furthermore, while Bob's relationship with the Rastafarian community is touched on, Steffens doesn't seem particularly interested in delving very deeply into this aspect of the story and the book suffers as a result. Loading comments… Trouble loading? I live the style too, through the words of others like the Bill Graham biography. See details. His portrayal of both Bunny Wailer and Peter Tosh is well wrought with their distinct, uncompromising personalties well defined. Paperback , pages. Want to Read saving…. I would recommend this book for any Marley lover or scholar as it does contain quite a varied and interesting collection of voices. Linton Kwesi Johnson Introduction. Other bios provide documentation and the results of research; this one provides only opinions. Written in the so called words of Bobs friends and associates , the book did not come close to living up to my expectations. Books by Roger Steffens. Steffens gives the band members of the Wailers their just due as they move from the local recording studios of Kingston to worldwide prominence and the difficulties they experienced in adjusting to life outside the insular world of Jamaica. However, this didn't actually have any quotes from him, just from people who worked with him or knew him Mar 13, Brian White rated it liked it. I knew most of them. And if everyone seems to think Island Records head Chris Blackwell to be such a vampire of JA culture, wouldn't a word or two from him in his defense be appropriate? Highly Recommended. -

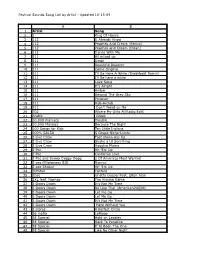

FS Master List-10-15-09.Xlsx

Festival Sounds Song List by Artist - Updated 10-15-09 A B 1 Artist Song 2 1 King Of House 3 112 U Already Know 4 112 Peaches And Cream (Remix) 5 112 Peaches and Cream [Clean] 6 112 Dance With Me 7 311 All mixed up 8 311 Down 9 311 Beautiful Disaster 10 311 Come Original 11 311 I'll Be Here A While (Breakbeat Remix) 12 311 I'll Be here a while 13 311 Love Song 14 311 It's Alright 15 311 Amber 16 311 Beyond The Grey Sky 17 311 Prisoner 18 311 Rub-A-Dub 19 311 Don't Tread on Me 20 702 Where My Girls At(Radio Edit) 21 Arabic Greek 22 10,000 maniacs Trouble 23 10,000 Maniacs Because The Night 24 100 Songs for Kids Ten Little Indians 25 100% SALSA S Grupo Niche-Lluvia 26 2 Live Crew Face Down Ass Up 27 2 Live Crew Shake a Lil Somthing 28 2 Live Crew Hoochie Mama 29 2 Pac Hit 'Em Up 30 2 Pac California Love 31 2 Pac and Snoop Doggy Dogg 2 Of Americas Most Wanted 32 2 pac f/Notorious BIG Runnin' 33 2 pac Shakur Hit 'Em Up 34 20thfox Fanfare 35 2pac Ghetto Gospel Feat. Elton John 36 2XL feat. Nashay The Kissing Game 37 3 Doors Down It's Not My Time 38 3 Doors Down Be Like That (AmericanPieEdit) 39 3 Doors Down Let me Go 40 3 Doors Down Let Me Go 41 3 Doors Down It's Not My Time 42 3 Doors Down Here Without You 43 3 Libras A Perfect Circle 44 36 mafia Lollipop 45 38 Special Hold on Loosley 46 38 Special Back To Paradise 47 38 Special If Id Been The One 48 38 Special Like No Other Night Festival Sounds Song List by Artist - Updated 10-15-09 A B 1 Artist Song 49 38 Special Rockin Into The Night 50 38 Special Saving Grace 51 38 Special Second Chance 52 38 Special Signs Of Love 53 38 Special The Sound Of Your Voice 54 38 Special Fantasy Girl 55 38 Special Caught Up In You 56 38 Special Back Where You Belong 57 3LW No More 58 3OH!3 Don't Trust Me 59 4 Non Blondes What's Up 60 50 Cent Just A Lil' Bit 61 50 Cent Window Shopper (Clean) 62 50 Cent Thug Love (ft. -

Chant Down Babylon: the Rastafarian Movement and Its Theodicy for the Suffering

Verge 5 Blatter 1 Chant Down Babylon: the Rastafarian Movement and Its Theodicy for the Suffering Emily Blatter The Rastafarian movement was born out of the Jamaican ghettos, where the descendents of slaves have continued to suffer from concentrated poverty, high unemployment, violent crime, and scarce opportunities for upward mobility. From its conception, the Rastafarian faith has provided hope to the disenfranchised, strengthening displaced Africans with the promise that Jah Rastafari is watching over them and that they will someday find relief in the promised land of Africa. In The Sacred Canopy , Peter Berger offers a sociological perspective on religion. Berger defines theodicy as an explanation for evil through religious legitimations and a way to maintain society by providing explanations for prevailing social inequalities. Berger explains that there exist both theodicies of happiness and theodicies of suffering. Certainly, the Rastafarian faith has provided a theodicy of suffering, providing followers with religious meaning in social inequality. Yet the Rastafarian faith challenges Berger’s notion of theodicy. Berger argues that theodicy is a form of society maintenance because it allows people to justify the existence of social evils rather than working to end them. The Rastafarian theodicy of suffering is unique in that it defies mainstream society; indeed, sociologist Charles Reavis Price labels the movement antisystemic, meaning that it confronts certain aspects of mainstream society and that it poses an alternative vision for society (9). The Rastas believe that the white man has constructed and legitimated a society that is oppressive to the black man. They call this society Babylon, and Rastas make every attempt to defy Babylon by refusing to live by the oppressors’ rules; hence, they wear their hair in dreads, smoke marijuana, and adhere to Marcus Garvey’s Ethiopianism. -

Paroles Et Traduction De «Iron Lion Zion

Paroles et traduction de «Iron Lion Zion» Iron Lion Zion (Fer Lion Zion*) I am on the rock and then I check a stock Je suis sur le rocher et je vérifie des provisions I have to run like a fugitive to save the life i live J'ai dû courir comme un fugitif pour sauver la vie que je vis I'm gonna be Iron like a Lion in Zion (repeat) Je vais être de fer comme un lion a Zion (bis) Iron Lion Zion Fer, lion, Zion I'm on the run but I ain't got no gun Je suis sur la course et je n'ai aucun pistolet. See they want to be the star Regarde, ils veulent devenir des étoiles So they fighting tribal war Voilà pourquoi ils font des guerres tribales. And they saying Iron like a Lion in Zion Et ils se disent Iron like a Lion in Zion, De fer comme un lion a Zion Iron, Lion, Zion Fer, lion, Zion I'm on the rock, (running and you running) Je suis sur le rocher (cours et tu cours) I take a stock, (running like a fugitive) Prenant des provisions (courant comme un fugitif) I had to run like a fugitive just to save the life i live J'ai dû courir comme un fugitif pour sauver la vie que je vis I'm gonna be Iron like a Lion in Zion (repeat) Je vais être de fer comme un lion a Sion (bis) Iron, Lion, Zion Fer, lion, Zion Iron, Lion, Zion Fer, lion, Zion Iron, Lion, Zion Fer, lion, Zion Iron like a Lion in Zion De fer comme un lion a Zion Iron like a Lion in Zion De fer comme un lion a Zion Iron like a Lion in Zion De fer comme un lion a Zion Explications sur les paroles de la chanson Iron Lion Zion est une chanson écrite et enregistrée en avril 1973 ou 1974 par le chanteur et auteur- compositeur jamaïcain Bob Marley. -

Hdnet Schedule for Mon. January 30, 2012 to Sun. February 5, 2012

HDNet Schedule for Mon. January 30, 2012 to Sun. February 5, 2012 Monday January 30, 2012 3:30 PM ET / 12:30 PM PT 6:00 AM ET / 3:00 AM PT HDNet Fights Visions of New York City DREAM New Year! 2011 - Former PRIDE Heavyweight Champion Fedor Emelianenko meets New York in all its striking juxtapositions of nature and modern progress, geometry and geog- Olympic Judo Gold Medalist Satoshi Ishii. Shinya Aoki defends the DREAM Lightweight Title raphy - the harbor from Lady Liberty’s perspective to Central Park as the birds experience it. against Satoru Kitaoka. 7:00 AM ET / 4:00 AM PT 5:00 PM ET / 2:00 PM PT Cheers Prison Break Diane Meets Mom - Diane’s nervous about meeting Frasier’s mother Hester, who’s a Riots, Drills and the Devil - Michael’s ploy to buy some work time by prompting a cellblock renowned psychologist. Hester’s pleasant during dinner, but when Frasier leaves them alone, lockdown leads to a full-scale riot; Nick convinces Veronica that he really does want to help she threatens to kill Diane if she continues to interfere with her son’s life. her; and Kellerman hires an inmate to kill Lincoln. 7:30 AM ET / 4:30 AM PT 6:00 PM ET / 3:00 PM PT Cheers JAG An American Family - Carla’s ex-husband returns with his new bride, demanding custody of Offensive Action - In a P-3 Squadron over the Pacific Ocean, Cmdr. O’Neil hounds Lt. Kersey their oldest son. The normally feisty Carla shocks everyone at the bar when she agrees to the during a mission. -

Rastalogy in Tarrus Riley's “Love Created I”

Rastalogy in Tarrus Riley’s “Love Created I” Darren J. N. Middleton Texas Christian University f art is the engine that powers religion’s vehicle, then reggae music is the 740hp V12 underneath the hood of I the Rastafari. Not all reggae music advances this movement’s message, which may best be seen as an anticolonial theo-psychology of black somebodiness, but much reggae does, and this is because the Honorable Robert Nesta Marley OM, aka Tuff Gong, took the message as well as the medium and left the Rastafari’s track marks throughout the world.1 Scholars have been analyzing such impressions for years, certainly since the melanoma-ravaged Marley transitioned on May 11, 1981 at age 36. Marley was gone too soon.2 And although “such a man cannot be erased from the mind,” as Jamaican Prime Minister Edward Seaga said at Marley’s funeral, less sanguine critics left others thinking that Marley’s demise caused reggae music’s engine to cough, splutter, and then die.3 Commentators were somewhat justified in this initial assessment. In the two decades after Marley’s tragic death, for example, reggae music appeared to abandon its roots, taking on a more synthesized feel, leading to electronic subgenres such as 1 This is the basic thesis of Carolyn Cooper, editor, Global Reggae (Kingston, Jamaica: Canoe Press, 2012). In addition, see Kevin Macdonald’s recent biopic, Marley (Los Angeles, CA: Magonlia Home Entertainment, 2012). DVD. 2 See, for example, Noel Leo Erskine, From Garvey to Marley: Rastafari Theology (Gainesville, FL: University Press of Florida, 2004); Dean MacNeil, The Bible and Bob Marley: Half the Story Has Never Been Told (Eugene, OR: Cascade Books, 2013); and, Roger Steffens, So Much Things to Say: The Oral History of Bob Marley, with an introduction by Linton Kwesi Johnson (New York and London: W.W. -

To See the 2018 Pier Concert Preview Guide

2 TWILIGHTSANTAMONICA.ORG REASON 1 #1 in Transfers for 27 Years APPLY AT SMC.EDU SANTA MONICA COMMUNITY COLLEGE DISTRICT BOARD OF TRUSTEES Barry A. Snell, Chair; Dr. Margaret Quiñones-Perez, Vice Chair; Dr. Susan Aminoff; Dr. Nancy Greenstein; Dr. Louise Jaffe; Rob Rader; Dr. Andrew Walzer; Alexandria Boyd, Student Trustee; Dr. Kathryn E. Jeffery, Superintendent/President Santa Monica College | 1900 Pico Boulevard | Santa Monica, CA 90405 | smc.edu TWILIGHTSANTAMONICA.ORG 3 2018 TWILIGHT ON THE PIER SCHEDULE SEPT 05 LATIN WAVE ORQUESTA AKOKÁN Jarina De Marco Quitapenas Sister Mantos SEPT 12 AUSTRALIA ROCKS THE PIER BETTY WHO Touch Sensitive CXLOE TWILIGHT ON THE PIER Death Bells SEPT 19 WELCOMES THE WORLD ISLAND VIBES f you close your eyes, inhale the ocean Instagram feeds, and serves as a backdrop Because the event is limited to the land- JUDY MOWATT Ibreeze and listen, you’ll hear music in in Hollywood blockbusters. mark, police can better control crowds and Bokanté every moment on the Santa Monica Pier. By the end of last year, the concerts had for the first time check bags. Fans will still be There’s the percussion of rubber tires reached a turning point. City leaders grappled allowed to bring their own picnics and Twilight Steel Drums rolling over knotted wood slats, the plinking with an event that had become too popular for water bottles for the event. DJ Danny Holloway of plastic balls bouncing in the arcade and its own good. Police worried they couldn’t The themes include Latin Wave, Australia the song of seagulls signaling supper. -

The Dub June 2018

1 Spanners & Field Frequency Sound System, Reading Dub Club 12.5.18 2 Editorial Dub Front cover – Indigenous Resistance: Ethiopia Dub Journey II Dear Reader, Welcome to issue 25 for the month of Levi. This is our 3rd anniversary issue, Natty Mark founding the magazine in June 2016, launching it at the 1st Mikey Dread Festival near Witney (an event that is also 3 years old this year). This summer sees a major upsurge in events involving members of The Dub family – Natty HiFi, Jah Lambs & Lions, Makepeace Promotions, Zion Roots, Swindon Dub Club, Field Frequency Sound System, High Grade and more – hence the launch of the new Dub Diary Newsletter at sessions. The aim is to spread the word about forthcoming gigs and sessions across the region, pulling different promoters’ efforts together. Give thanks to the photographers who have allowed us to use their pictures of events this month. We welcome some new writers this month too – thanks you for stepping up Benjamin Ital and Eric Denham (whose West Indian Music Appreciation Society newsletter ran from 1966 to 1974 and then from 2014 onwards). Steve Mosco presents a major interview with U Brown from when they recorded an album together a few years ago. There is also an interview with Protoje, a conversation with Jah9 from April’s Reggae Innovations Conference, a feature on the Indigenous Resistance collective, and a feature on Augustus Pablo. Welcome to The Dub Editor – Dan-I [email protected] The Dub is available to download for free at reggaediscography.blogspot.co.uk and rastaites.com The Dub magazine is not funded and has no sponsors. -

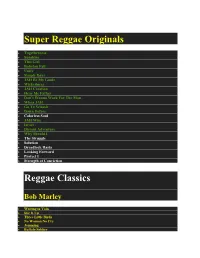

View Song List

Super Reggae Originals Togetherness Sunshine This Girl Babylon Fall Unify Simple Days JAH Be My Guide Wickedness JAH Creation Hear Me Father Don’t Wanna Work For The Man Whoa JAH Go To Selassie Down Before Colorless Soul JAH Wise Israel Distant Adventure Why Should I The Struggle Solution Dreadlock Rasta Looking Forward Protect I Strength of Conviction Reggae Classics Bob Marley Waiting in Vain Stir It Up Three Little Birds No Woman No Cry Jamming Buffalo Soldier I Shot the Sherriff Mellow Mood Forever Loving JAH Lively Up Yourself Burning and Looting Hammer JAH Live Gregory Issacs Number One Tune In Night Nurse Sunday Morning Soon Forward Cool Down the Pace Dennis Brown Love and Hate Need a Little Loving Milk and Honey Run Too Tuff Revolution Midnite Ras to the Bone Jubilees of Zion Lonely Nights Rootsman Zion Pavilion Peter Tosh Legalize It Reggaemylitis Ketchie Shuby Downpressor Man Third World 96 Degrees in the Shade Roots with Quality Reggae Ambassador Riddim Haffe Rule Sugar Minott Never Give JAH Up Vanity Rough Ole Life Rub a Dub Don Carlos People Unite Credential Prophecy Civilized Burning Spear Postman Columbus Burning Reggae Culture Two Sevens Clash See Dem a Come Slice of Mt Zion Israel Vibration Same Song Rudeboy Shuffle Cool and Calm Garnet Silk Zion in a Vision It’s Growing Passing Judgment Yellowman Operation Eradication Yellow Like Cheese Alton Ellis Just A Guy Breaking Up is Hard to Do Misty in Roots Follow Fashion Poor and Needy -

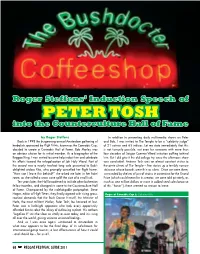

Peter Tosh Into the Counterculture Hall of Fame

Roger Steffens’ Induction Speech of PETER TOSH into the Counterculture Hall of Fame by Roger Steffens In addition to presenting daily multi-media shows on Peter Back in 1998 the burgeoning annual Amsterdam gathering of and Bob, I was invited to The Temple to be a “celebrity judge” herbalists sponsored by High Times, known as the Cannabis Cup, of 21 sativas and 63 indicas. Let me state immediately that this decided to create a Cannabis Hall of Fame. Bob Marley was is not humanly possible, not even for someone with more than an obvious choice for its initial member. As a biographer of the four decades of Saigon-Commie-Weed initiation puffing behind Reggae King, I was invited to come help induct him and celebrate him. But I did give it the old college try, once the afternoon show his efforts toward the re-legalization of Jah Holy Weed. Part of was concluded. Andrew Tosh was an almost constant visitor to the award was a nearly two-foot long cola presented to Bob’s the aerie climes of The Temple – five stories up a terribly narrow delighted widow Rita, who promptly cancelled her flight home. staircase whose boards were thin as rulers. Once we were there, “How can I leave this behind?” she asked me later in her hotel surrounded by shelves of jars of strains in contention for the Grand room, as she rolled a snow cone spliff the size of a small tusk. Prize (which could mean for its creator, we were told privately, as Ten years later, the Hall broadened to include other bohemian much as one million dollars or more in added seed sales because fellow travelers, and changed its name to the Counterculture Hall of this “honor”), there seemed no reason to leave. -

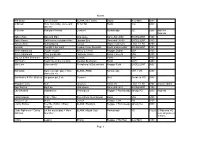

Sheet1 Page 1 809 Band Jam Session BLANK (Hit

Sheet1 809 Band Jam Session BLANK (Hit Factor) Digital Near Mint $200 Al Brown Here I Am baby, come and Tit for Tat Roots VG+ $200 take me Al Senior Bonopart Retreat Coxsone Rocksteady VG $200 Old time Repress Baby Cham Man and Man Xtra Large Dancehall 2000 EXCELLENT $100 Baby Wayne Gal fi come in a dance free Upstairs Ent. Dancehall 95-99 EXCELLENT $100 Banana Man Ruling Sound Taurus Digital clash tune EXCELLENT $250 Benaiah Tonight is the night Cosmic Force Records Roots instrumental EXCELLENT $150 Beres Hammond Double trouble Steely & Clevie Reggae Digital VG+ $150 Beres Hammond They gonna talk Harmony House Roots // Lovers VG+ $150 Big Joe & Bim Sherman Natty cale Scorpio Roots VG+ $400 Big Youth Touch me in the morning Agustus Buchanan Roots VG++ $200 Billy Cole Extra careful Recrational & Educational Reggae Funk EXCELLENT $600 Bob Andy Games people play // Sun BLANK (FRM) Rocksteady VG+ // VG $400 shines for me Bob Marley & The Wailers I'm gonna put it on Coxsone SKA Good+ to VG- $350 Brigadier Jerry Pain Jwyanza Roots DJ EXCELLENT $200 answer riddim Buju Banton Big it up Mad House Dancehall 90's EXCELLENT $100 Carl Dawkins Satisfaction Techniques Reggae // Rocksteady Strong VG $200 Repress Carol Kalphat Peace Time Roots Rock International Roots VG+ $300 Chosen Few Shaft Crystal Reggae Funk VG $250 Clancy Eccles Feel the rhythm // Easy BLANK (Randy's) Reggae // Rocksteady Strong VG $500 snappin Clyde Alphonso // Carey Let the music play // More BLANK (Muzik City) Rocksteady VG $1200 El Flip toca VG Johnson Scorcher pero sin peso