Species Level Patterns in 13C and 15N Abundance of Ectomycorrhizal And

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

G. Gulden & E.W. Hanssen Distribution and Ecology of Stipitate Hydnaceous Fungi in Norway, with Special Reference to The

DOI: 10.2478/som-1992-0001 sommerfeltia 13 G. Gulden & E.W. Hanssen Distribution and ecology of stipitate hydnaceous fungi in Norway, with special reference to the question of decline 1992 sommerfeltia~ J is owned and edited by the Botanical Garden and Museum, University of Oslo. SOMMERFELTIA is named in honour of the eminent Norwegian botanist and clergyman S0ren Christian Sommerfelt (1794-1838). The generic name Sommerfeltia has been used in (1) the lichens by Florke 1827, now Solorina, (2) Fabaceae by Schumacher 1827, now Drepanocarpus, and (3) Asteraceae by Lessing 1832, nom. cons. SOMMERFELTIA is a series of monographs in plant taxonomy, phytogeo graphy, phytosociology, plant ecology, plant morphology, and evolutionary botany. Most papers are by Norwegian authors. Authors not on the staff of the Botanical Garden and Museum in Oslo pay a page charge of NOK 30.00. SOMMERFEL TIA appears at irregular intervals, normally one article per volume. Editor: Rune Halvorsen 0kland. Editorial Board: Scientific staff of the Botanical Garden and Museum. Address: SOMMERFELTIA, Botanical Garden and Museum, University of Oslo, Trondheimsveien 23B, N-0562 Oslo 5, Norway. Order: On a standing order (payment on receipt of each volume) SOMMER FELTIA is supplied at 30 % discount. Separate volumes are supplied at the prices indicated on back cover. sommerfeltia 13 G. Gulden & E.W. Hanssen Distribution and ecology of stipitate hydnaceous fungi in Norway, with special reference to the question of decline 1992 ISBN 82-7420-014-4 ISSN 0800-6865 Gulden, G. and Hanssen, E.W. 1992. Distribution and ecology of stipitate hydnaceous fungi in Norway, with special reference to the question of decline. -

Ectomycorrhizal Fungi at Tree Line in the Canadian Rockies II

Mycorrhiza (2001) 10:217–229 © Springer-Verlag 2001 ORIGINAL PAPER Gavin Kernaghan Ectomycorrhizal fungi at tree line in the Canadian Rockies II. Identification of ectomycorrhizae by anatomy and PCR Accepted: 15 October 2000 Abstract Ectomycorrhizae of Picea, Abies, Dryas and northern/montane ectomycorrhizal fungi (Kernaghan and Salix were collected at two tree-line sites at an altitude of Currah 1998). The species composition and relative 2,000–2,500 m in the Front Range of the Canadian abundance of ectomycorrhizae in montane habitats are Rockies. Six mycobionts were identified to species by still poorly understood (Gardes and Dahlberg 1996). On- direct comparison of PCR-amplified ribosomal DNA ly recently have efforts been made to identify and de- with that from locally collected sporocarps. Four of these scribe ectomycorrhizae from subalpine forests and adja- (Cortinarius calochrous, Hydnellum caeruleum, Laccaria cent alpine zones (Debaud et al. 1981; Debaud 1987; montana and Russula integra) are newly described sym- Treu 1990; Graf and Brunner 1996; Kernaghan et al. bioses. Twelve other ectomycorrhizae had no conspecific 1997). RFLP match with the sporocarps analyzed, but were Studies such as these have used a variety of methods identified to species, genus or family by anatomical for mycobiont identification: tracing hyphal connections comparison with sporocarps and literature descriptions between sporocarps and mycorrhizae (Agerer 1991a), or by phenetic clustering based on the presence or ab- comparing field-collected mycorrhizae to mycorrhizae sence of restriction fragments. The majority of species synthesized in-vitro (Fortin et al. 1980; Molina and identified have northern and/or montane distributions. Palmer 1982), comparing cultures obtained from spor- Mycorrhizae are described on the basis of both anatomi- ocarps to those from mycorrhizae (Chu-Chou 1979; cal and molecular characters. -

Fungi of the Fortuna Forest Reserve: Taxonomy and Ecology with Emphasis on Ectomycorrhizal Communities

bioRxiv preprint doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/2020.04.16.045724; this version posted April 18, 2020. The copyright holder for this preprint (which was not certified by peer review) is the author/funder, who has granted bioRxiv a license to display the preprint in perpetuity. It is made available under aCC-BY-NC 4.0 International license. Fungi of the Fortuna Forest Reserve: Taxonomy and ecology with emphasis on ectomycorrhizal communities Adriana Corrales1 and Clark L. Ovrebo2 1 Department of Biology, Faculty of Natural Sciences, Universidad del Rosario. Bogota, 111221, Colombia. 2 Department of Biology, University of Central Oklahoma. Edmond, OK. USA. ABSTRACT Panamanian montane forests harbor a high diversity of fungi, particularly of ectomycorrhizal (ECM) fungi, however their taxonomy and diversity patterns remain for the most part unexplored. Here we present state of the art fungal taxonomy and diversity patterns at Fortuna Forest Reserve based on morphological and molecular identification of over 1,000 fruiting body collections of macromycetes made over a period of five years. We compare these new results with previously published work based on environmental sampling of Oreomunnea mexicana root tips. We compiled a preliminary list of species and report 22 new genera and 29 new fungal species for Panama. Based on fruiting body collection data we compare the species composition of ECM fungal communities associated with Oreomunnea stands across sites differing in soil fertility and amount of rainfall. We also examine the effect of a long-term nitrogen addition treatment on the fruiting body production of ECM fungi. Finally, we discuss the biogeographic importance of Panama collections which fill in the knowledge gap of ECM fungal records between Costa Rica and Colombia. -

Phellodon Secretus (Basidiomycota ), a New Hydnaceous Fungus.From Northern Pine Woodlands

Karstenia 43: 37--44, 2003 Phellodon secretus (Basidiomycota ), a new hydnaceous fungus.from northern pine woodlands TUOMO NIEMELA, JUHA KJNNUNEN, PERTII RENVALL and DMITRY SCHIGEL NIEMELA, T. , KINNUNEN, J. , RENVALL, P. & SCHIGEL, D. 2003: Phellodon secretus (Basidiomycota), a new hydnaceous fungus from northern pine woodlands. Karstenia 43: 37-44. 2003. Phellodon secretus Niemela & Kinnunen (Basidiomycota, Thelephorales) resembles Phellodon connatus (Schultz : Fr.) P. Karst., but differs in havi ng a thinner stipe, cottony soft pileus, and smaller and more globose spores. Its ecology is peculiar: it is found in dry, old-growth pine woodlands, growing in sheltered places under strongly decayed trunks or rootstocks of pine trees, where there is a gap of only a few centim eters between soil and wood. Basidiocarps emerge from humus as needle-like, ca. I mm thick, black stipes, and the pileus unfolds only after the stipe tip has contacted the overhanging wood. In its ecology and distribution the species resembles Hydnellum gracilipes (P. Karst.) P. Karst. It seems to be extremely rare, found in Northern boreal and Middle boreal vegetation zones, in areas with fairly continental climate. Key words: Aphyllophorales, Phellodon, hydnaceous fungi, taxonomy Tuomo Niemela, Juha Kinnunen & Dmitry Schigel, Finnish Museum of Natural His tory, Botanical Museum, P.O. Box 7, FIN-00014 University of Helsinki, Finland Pertti Renvall, Kuopio Natural History Museum, Myhkyrinkatu 22, FIN-70100 Kuo pio, Finland Introduction Virgin pine woodlands of northern Europe make a eventually dying while standing. Such dead pine specific environment for fungi. The barren sandy trees may keep standing for another 200-500 soil, spaced stand of trees and scanty lower veg years, losing their bark and thinner branches: in etation result in severe drought during sunny this way the so-called kelo trees develop, com summer months, in particular because such wood mon and characteristic for northern old-growth lands are usually situated on exposed hillsides, pine woodlands. -

Taxonomy and Systematics of Thelephorales – Glimpses Into Its Hidden Hyperdiversity

Taxonomy and Systematics of Thelephorales – Glimpses Into its Hidden Hyperdiversity Sten Svantesson 2020 UNIVERSITY OF GOTHENBURG Faculty of Science Department of Biological and Environmental Sciences Opponent Prof. Annemieke Verbeken Examiner Prof. Bengt Oxelman Supervisors Associate Prof. Ellen Larsson & Profs. Karl-Henrik Larsson, Urmas Kõljalg Associate Profs. Tom W. May, R. Henrik Nilsson © Sten Svantesson All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted, in any form or by any means, without written permission. Svantesson S (2020) Taxonomy and systematics of Thelephorales – glimpses into its hidden hyperdiversity. PhD thesis. Department of Biological and Environmental Sciences, University of Gothenburg, Gothenburg, Sweden. Många är långa och svåra att fånga Cover image: Pseudotomentella alobata, a newly described species in the Pseudotomentella tristis group. Många syns inte men finns ändå Många är gula och fula och gröna ISBN print: 978-91-8009-064-3 Och sköna och röda eller blå ISBN digital: 978-91-8009-065-0 Många är stora som hus eller så NMÄ NENMÄRK ANE RKE VA ET SV T Digital version available at: http://hdl.handle.net/2077/66642 S Men de flesta är små, mycket små, mycket små Trycksak Trycksak 3041 0234 – Olle Adolphson, från visan Okända djur Printed by Stema Specialtryck AB 3041 0234 © Sten Svantesson All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted, in any form or by any means, without written permission. Svantesson S (2020) Taxonomy and systematics of Thelephorales – glimpses into its hidden hyperdiversity. PhD thesis. Department of Biological and Environmental Sciences, University of Gothenburg, Gothenburg, Sweden. Många är långa och svåra att fånga Cover image: Pseudotomentella alobata, a newly described species in the Pseudotomentella tristis group. -

The Taxonomy and Ecology of Wood Decay Fungi in Eucalyptus Obliqua Trees and Logs in the Wet Sclerophyll Forests of Southern Tasmania

The taxonomy and ecology of wood decay fungi in Eucalyptus obliqua trees and logs in the wet sclerophyll forests of southern Tasmania by Anna J. M. Hopkins B.Sc. (Hons.) School of Agricultural Science, University of Tasmania Cooperative Research Centre for Forestry A research thesis submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy January, 2007 Declarations This thesis contains no material which has been accepted for a degree or diploma in any university or other institution. To the best of my knowledge, this thesis contains no material previously published or written by another person, except where due acknowledgment is made in the text. Anna J. M. Hopkins This thesis may be made available for loan and limited copying in accordance with the Copyright Act of 1968. Anna J. M. Hopkins ii Abstract The wet sclerophyll forests in southern Tasmania are dominated by Eucalyptus obliqua and are managed on a notional silvicultural rotation length of 80 to 100 years. Over time, this will lead to a simplified stand structure with a truncated forest age and thus reduce the proportion of coarse woody debris (CWD), such as old living trees and large diameter logs, within the production forest landscape. Course woody debris is regarded as a critical habitat for biodiversity management in forest ecosystems. Fungi, as one of the most important wood decay agents, are key to understanding and managing biodiversity associated with decaying wood. In Australia, wood-inhabiting fungi are poorly known and the biodiversity associated with CWD has not been well studied. This thesis describes two studies that were undertaken to examine the importance of CWD as habitat for wood-inhabiting fungi in the wet sclerophyll forests of Tasmania. -

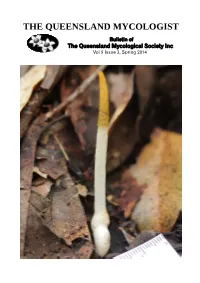

A Most Mysterious Fungus 14

THE QUEENSLAND MYCOLOGIST Bulletin of The Queensland Mycological Society Inc Vol 9 Issue 3, Spring 2014 The Queensland Mycological Society ABN No 18 351 995 423 Internet: http://qldfungi.org.au/ Email: info [at] qldfungi.org.au Address: PO Box 5305, Alexandra Hills, Qld 4161, Australia QMS Executive Society Objectives President The objectives of the Queensland Mycological Society are to: Frances Guard 07 5494 3951 1. Provide a forum and a network for amateur and professional info[at]qldfungi.org.au mycologists to share their common interest in macro-fungi; Vice President 2. Stimulate and support the study and research of Queensland macro- Patrick Leonard fungi through the collection, storage, analysis and dissemination of 07 5456 4135 information about fungi through workshops and fungal forays; patbrenda.leonard[at]bigpond.com 3. Promote, at both the state and federal levels, the identification of Secretary Queensland’s macrofungal biodiversity through documentation and publication of its macro-fungi; Ronda Warhurst 4. Promote an understanding and appreciation of the roles macro-fungal info[at]qldfungi.org.au biodiversity plays in the health of Queensland ecosystems; and Treasurer 5. Promote the conservation of indigenous macro-fungi and their relevant Leesa Baker ecosystems. Minutes Secretary Queensland Mycologist Ronda Warhurst The Queensland Mycologist is issued quarterly. Members are invited to submit short articles or photos to the editor for publication. Material can Membership Secretary be in any word processor format, but not PDF. The deadline for Leesa Baker contributions for the next issue is 1 November 2014, but earlier submission is appreciated. Late submissions may be held over to the next edition, Foray Coordinator depending on space, the amount of editing required, and how much time Frances Guard the editor has. -

Bankera Violascens and Sarcodon Versipellis

C z e c h m y c o l . 49 (1), 1996 Notes on two hydnums - Bankera violascens and Sarcodon versipellis P e t r H r o u d a Department of Systematic Botany and Geobotany, Masaryk University, Kotlářská 2, 61137 Brno, Czech Republic Hrouda P. (1996): Notes on two hydnums - Bankera violascens and Sarcodon versipellis. - Czech Mycol. 49: 35-39 This article deals with two questions concerning to hydnaceous fungi. I do not accept the name Bankera cinerea (Bull.: Fr.) Rauschert for Bankera violascens (Alb. et Schw.: Fr.) Pouz. The reason is that Bulliard’s illustration of Hydnum cinereum, on which Rauschert based his combination, in my opinion does not show a species of the genus Bankera. The characters, on which this statement is based, are given. The specimens of Sarcodon balsamiodorus Pouz. in schaedis from herbaria (PRM, BRA) belong, also according to the description of fresh material, to Sarcodon versipellis (Fr.) Quel. Key words: Combination, Bankera cinerea, Bulliard’s illustration, exsiccates, Sarcodon balsamiodorus. Hrouda P. (1996): Poznámky ke dvěma lošákům - bělozubu nafialovělému a lošáku balzámovému. - Czech Mycol. 49: 35-39 článek komentuje dva otazníky vyvstavší při studiu lošáků. Neakceptuji jméno Bankera cinerea (Bull.: Fr.) Rauschert pro Bankera violascens (Alb. et Schw.: Fr.) Pouz., neboť exempláře Hydnum cinereum na Bulliardově ilustraci, na kterých Rauschert zakládá svou kombinaci, podle mého názoru nejsou jedinci rodu Bankera. Podávám popis znaků, na kterých zakládám své tvrzení. Položky Sarcodon balsamiodorus Pouz. in schaedis, uložené v pražském (PRM) a bratislav ském (BRA) herbáři, patří podle popisu čerstvého materiálu k Sarcodon versipellis (Fr.) Quél. -

Phaeocollybia Olivacea A.H. Smith ROD Name Phaeocollybia Olivacea Family Cortinariaceae Morphological Habit Mushroom

S3 - 84 Phaeocollybia olivacea A.H. Smith ROD name Phaeocollybia olivacea Family Cortinariaceae Morphological Habit mushroom Description: CAP 40-110 mm in diam., umbonate, viscid to glutinous, uniformly dark olive overall when young but later becoming pale brown to olive-brown. GILLS nearly free, pale tan when young but soon becoming rusty brown with wavy to eroded edges. STEM up to 200 mm long over all with aerial portion up to 80 mm, 10-20 mm in diam. at apex, equal or enlarged down to the ground where it can reach 40 mm across, stuffed with an off-white conspicuous fibrillose pith. PSEUDORHIZA tapered, long, origin well below ground level. ODOR of raw cucumbers, soon fading. TASTE not distinct. PILEIPELLIS a two-layered ixocutis with a thick, gelatinous, hyaline top layer and a bottom layer containing inflated floccose hyphae with brown walls in KOH. CHEILOCYSTIDIA thin walled, clavate. CLAMP CONNECTIONS absent. SPORES ovate with an abrupt projecting snout in face view, 8-11 x 5- 6.5 µm, walls warty-rugulose roughened except over smooth apical beak and suprahilar plage. Distinguishing Features: Phaeocollybia pseudofestiva also produces green-capped sporocarps, but they are smaller, usually hollow-stemmed, producing much shorter, rounder spores, and have refractive, capitulate cheilocystidia with thick-walled, narrow necks. Distribution: Endemic to western United States from central Oregon coast south to Santa Cruz Co., California. CALIFORNIA, Del Norte Co., Crescent City; Jedediah Smith Redwoods State Park, west of Smith River bridge -

Fungal Diversity in a Transgenic Poplar Plantation and the Role of Ectomycorrhizal Fungi for Tree Performance Under

Fungal diversity in a transgenic poplar plantation and the role of ectomycorrhizal fungi for tree performance under field and controlled drought stress conditions Dissertation zur Erlangung des Doktorgrades der Mathematisch-Naturwissenschaftlichen Fakultät der Georg-August-Universität Göttingen Vorgelegt von Dipl. Biologin Lara Danielsen aus Flensburg Göttingen, Oktober 2012 Referent: Prof. Dr. Andrea Polle Koreferent: Prof. Dr. Stefan Scheu Tag der mündlichen Prüfung: 30. November 2012 Table of contents Table of Contents Summary………………………………………………………………………………………. V Zusammenfassung………………………………………………………………………….. VIII 1 Introduction…………………………………………………………………................... 1 1.1 Populus spp. as model organism …………………...…….…….………………… 2 1.2 Biodiversity and fungal community structure………….……….…………………. 2 1.3 Mycorrhizal fungi………………………………………………..…………………… 4 1.4 Functional traits of ECM fungi…………………………… ……………………….. 5 1.5 Research topics addressed in this thesis..……………………………………….. 6 1.6 References…………………………………………………………………………... 7 2 Fungal soil communities in a young transgenic poplar plantation form a rich reservoir for fungal root communities……………………………………………… 12 Abstract……………………………………………………………………………………. 13 2.1 Introduction………………………………………………………………………….. 14 2.2 Material and Methods...……...…………………………………………………….. 16 2.2.1 Plant material and study site…………………………………………………. 16 2.2.2 Sampling strategy……………...……………………………………………… 17 2.2.3 Soil analyses……………...…………………………………………………… 17 2.2.4 DNA extraction and quality check………………………….......................... -

<I>Rickenella Fibula</I>

University of Tennessee, Knoxville TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange Masters Theses Graduate School 8-2017 Stable isotopes, phylogenetics, and experimental data indicate a unique nutritional mode for Rickenella fibula, a bryophyte- associate in the Hymenochaetales Hailee Brynn Korotkin University of Tennessee, Knoxville, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://trace.tennessee.edu/utk_gradthes Part of the Evolution Commons Recommended Citation Korotkin, Hailee Brynn, "Stable isotopes, phylogenetics, and experimental data indicate a unique nutritional mode for Rickenella fibula, a bryophyte-associate in the Hymenochaetales. " Master's Thesis, University of Tennessee, 2017. https://trace.tennessee.edu/utk_gradthes/4886 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange. It has been accepted for inclusion in Masters Theses by an authorized administrator of TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange. For more information, please contact [email protected]. To the Graduate Council: I am submitting herewith a thesis written by Hailee Brynn Korotkin entitled "Stable isotopes, phylogenetics, and experimental data indicate a unique nutritional mode for Rickenella fibula, a bryophyte-associate in the Hymenochaetales." I have examined the final electronic copy of this thesis for form and content and recommend that it be accepted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Science, with a major in Ecology -

A Compilation for the Iberian Peninsula (Spain and Portugal)

Nova Hedwigia Vol. 91 issue 1–2, 1 –31 Article Stuttgart, August 2010 Mycorrhizal macrofungi diversity (Agaricomycetes) from Mediterranean Quercus forests; a compilation for the Iberian Peninsula (Spain and Portugal) Antonio Ortega, Juan Lorite* and Francisco Valle Departamento de Botánica, Facultad de Ciencias, Universidad de Granada. 18071 GRANADA. Spain With 1 figure and 3 tables Ortega, A., J. Lorite & F. Valle (2010): Mycorrhizal macrofungi diversity (Agaricomycetes) from Mediterranean Quercus forests; a compilation for the Iberian Peninsula (Spain and Portugal). - Nova Hedwigia 91: 1–31. Abstract: A compilation study has been made of the mycorrhizal Agaricomycetes from several sclerophyllous and deciduous Mediterranean Quercus woodlands from Iberian Peninsula. Firstly, we selected eight Mediterranean taxa of the genus Quercus, which were well sampled in terms of macrofungi. Afterwards, we performed a database containing a large amount of data about mycorrhizal biota of Quercus. We have defined and/or used a series of indexes (occurrence, affinity, proportionality, heterogeneity, similarity, and taxonomic diversity) in order to establish the differences between the mycorrhizal biota of the selected woodlands. The 605 taxa compiled here represent an important amount of the total mycorrhizal diversity from all the vegetation types of the studied area, estimated at 1,500–1,600 taxa, with Q. ilex subsp. ballota (416 taxa) and Q. suber (411) being the richest. We also analysed their quantitative and qualitative mycorrhizal flora and their relative richness in different ways: woodland types, substrates and species composition. The results highlight the large amount of mycorrhizal macrofungi species occurring in these mediterranean Quercus woodlands, the data are comparable with other woodland types, thought to be the richest forest types in the world.