And Other Essays About Music

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Sade the Best of Sade Mp3, Flac, Wma

Sade The Best Of Sade mp3, flac, wma DOWNLOAD LINKS (Clickable) Genre: Electronic Album: The Best Of Sade Country: Europe Released: 2000 Style: Downtempo MP3 version RAR size: 1237 mb FLAC version RAR size: 1598 mb WMA version RAR size: 1994 mb Rating: 4.6 Votes: 279 Other Formats: TTA AHX FLAC VOC AIFF MP1 RA Tracklist Hide Credits 1 Your Love Is King 3:41 2 Hang On To Your Love 4:32 Smooth Operator 3 4:21 Songwriter [Song Writer] – St. John* 4 Jezebel 5:30 The Sweetest Taboo 5 4:38 Songwriter [Song Writer] – Ditcham* 6 Is It A Crime 6:23 Never As Good As The First Time 7 3:59 Producer – Rogan*, Pela*Vocals – Jake Jacas 8 Love Is Stronger Than Pride 4:20 Paradise 9 3:39 Guitar – Gordon Hunte 10 Nothing Can Come Between Us 3:56 11 No Ordinary Love 7:22 12 Like A Tattoo 3:41 Kiss Of Life 13 4:12 Arranged By [Strings] – Nick Ingman Please Send Me Someone To Love 14 Drums – Trevor MurrellGuitar – Gordon HuntePercussion – Karl Vanden Bossche*Producer, 3:43 Mixed By [Mixer] – Hein HovenSongwriter [Song Writer] – Percy Mayfield 15 Cherish The Day 6:19 Pearls 16 4:33 Arranged By [Strings] – Nick IngmanCello, Soloist – Tony Pleeth* Companies, etc. Phonographic Copyright (p) – Sony Music Entertainment (UK) Ltd. Copyright (c) – Sony Music Entertainment (UK) Ltd. Recorded At – Power Plant Studios Recorded At – Studio Miraval Recorded At – Compass Point Studios Recorded At – Studio Marcadet Recorded At – Condulmer Recording Studios Recorded At – Ridge Farm Studios Recorded At – The Hit Factory, London Recorded At – Conway Studios Recorded At – Ameraycan Studios Mastered At – Sterling Sound Published By – Angel Music Ltd. -

The Doors”—The Doors (1967) Added to the National Registry: 2014 Essay by Richie Unterberger (Guest Post)*

“The Doors”—The Doors (1967) Added to the National Registry: 2014 Essay by Richie Unterberger (guest post)* Original album cover Original label The Doors One of the most explosive debut albums in history, “The Doors” boasted an unprecedented fusion of rock with blues, jazz, and classical music. With their hypnotic blend of Ray Manzarek’s eerie organ, Robby Krieger’s flamenco-flecked guitar runs, and John Densmore’s cool jazz-driven drumming, the band were among the foremost pioneers of California psychedelia. Jim Morrison’s brooding, haunting vocals injected a new strand of literate poetry into rock music, exploring both the majestic highs and the darkest corners of the human experience. The Byrds, Bob Dylan, and other folk-rockers were already bringing more sophisticated lyrics into rock when the Doors formed in Los Angeles in the summer of 1965. Unlike those slightly earlier innovators, however, the Doors were not electrified folkies. Indeed, their backgrounds were so diverse, it’s a miracle they came together in the first place. Chicago native Manzarek, already in his late 20s, was schooled in jazz and blues. Native Angelenos Krieger and Densmore, barely in their 20s, when the band started to generate a local following, had more open ears to jazz and blues than most fledgling rock musicians. The charismatic Morrison, who’d met Manzarek when the pair were studying film at the University of California at Los Angeles, had no professional musical experience. He had a frighteningly resonant voice, however, and his voracious reading of beat literature informed the poetry he’d soon put to music. -

Songs by Artist

Reil Entertainment Songs by Artist Karaoke by Artist Title Title &, Caitlin Will 12 Gauge Address In The Stars Dunkie Butt 10 Cc 12 Stones Donna We Are One Dreadlock Holiday 19 Somethin' Im Mandy Fly Me Mark Wills I'm Not In Love 1910 Fruitgum Co Rubber Bullets 1, 2, 3 Redlight Things We Do For Love Simon Says Wall Street Shuffle 1910 Fruitgum Co. 10 Years 1,2,3 Redlight Through The Iris Simon Says Wasteland 1975 10, 000 Maniacs Chocolate These Are The Days City 10,000 Maniacs Love Me Because Of The Night Sex... Because The Night Sex.... More Than This Sound These Are The Days The Sound Trouble Me UGH! 10,000 Maniacs Wvocal 1975, The Because The Night Chocolate 100 Proof Aged In Soul Sex Somebody's Been Sleeping The City 10Cc 1Barenaked Ladies Dreadlock Holiday Be My Yoko Ono I'm Not In Love Brian Wilson (2000 Version) We Do For Love Call And Answer 11) Enid OS Get In Line (Duet Version) 112 Get In Line (Solo Version) Come See Me It's All Been Done Cupid Jane Dance With Me Never Is Enough It's Over Now Old Apartment, The Only You One Week Peaches & Cream Shoe Box Peaches And Cream Straw Hat U Already Know What A Good Boy Song List Generator® Printed 11/21/2017 Page 1 of 486 Licensed to Greg Reil Reil Entertainment Songs by Artist Karaoke by Artist Title Title 1Barenaked Ladies 20 Fingers When I Fall Short Dick Man 1Beatles, The 2AM Club Come Together Not Your Boyfriend Day Tripper 2Pac Good Day Sunshine California Love (Original Version) Help! 3 Degrees I Saw Her Standing There When Will I See You Again Love Me Do Woman In Love Nowhere Man 3 Dog Night P.S. -

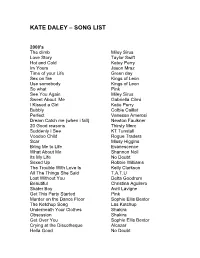

Kate Daley – Song List

KATE DALEY – SONG LIST 2000's The climb Miley Sirus Love Story Taylor Swift Hot and Cold Katey Perry Im Yours Jason Mraz Time of your Life Green day Sex on fire Kings of Leon Use somebody Kings of Leon So what Pink See You Again Miley Sirus Sweet About Me Gabriella Cilmi I Kissed a Girl Katie Perry Bubbly Colbie Caillat Perfect Vanessa Amerosi Dream Catch me (when i fall) Newton Faulkner 20 Good reasons Thirsty Merc Suddenly I See KT Tunstall Voodoo Child Rogue Traders Scar Missy Higgins Bring Me to Life Evanescence What About Me Shannon Noll Its My Life No Doubt Sexed Up Robbie Williams The Trouble With Love Is Kelly Clarkson All The Things She Said T.A.T.U Lost Without You Delta Goodrem Beautiful Christina Aguilero Skater Boy Avril Lavigne Get This Party Started Pink Murder on the Dance Floor Sophie Ellis Bextor The Ketchup Song Las Ketchup Underneath Your Clothes Shakira Obsession Shakira Get Over You Sophie Ellis Bextor Crying at the Discotheque Alcazar Hella Good No Doubt Lets Get Loud Jennifer Lopez Don’t Stop Moving S Club 7 Cant Get you Out of My Head Kylie Minogue I’m Like a Bird Nelly Fertado Absolutely Everybody Vanessa Amorosi Fallin’ Alicia Keys I Need Somebody Bardot Lady marmalade Moulin Rouge Drops of Jupiter Train Out of Reach Gabrielle (Bridgett Jones Dairy) Hit em up in Style Blu Cantrell Breathless The Corrs Buses and trains Bachelor Girl Shine Vanessa Amorosi What took you so long Emma B Overload Sugarbabes Cant Fight the Moonlight Leeann Rhymes (Coyote Ugly) Sunshine on a Rainy Day Christine Anu On a Night Like This -

2014–2015 Season Sponsors

2014–2015 SEASON SPONSORS The City of Cerritos gratefully thanks our 2014–2015 Season Sponsors for their generous support of the Cerritos Center for the Performing Arts. YOUR FAVORITE ENTERTAINERS, YOUR FAVORITE THEATER If your company would like to become a Cerritos Center for the Performing Arts sponsor, please contact the CCPA Administrative Offices at 562-916-8510. THE CERRITOS CENTER FOR THE PERFORMING ARTS (CCPA) thanks the following current CCPA Associates donors who have contributed to the CCPA’s Endowment Fund. The Endowment Fund was established in 1994 under the visionary leadership of the Cerritos City Council to ensure that the CCPA would remain a welcoming, accessible, and affordable venue where patrons can experience the joy of entertainment and cultural enrichment. For more information about the Endowment Fund or to make a contribution, please contact the CCPA Administrative Offices at (562) 916-8510. MARQUEE Sandra and Bruce Dickinson Diana and Rick Needham Eleanor and David St. Clair Mr. and Mrs. Curtis R. Eakin A.J. Neiman Judy and Robert Fisher Wendy and Mike Nelson Sharon Kei Frank Jill and Michael Nishida ENCORE Eugenie Gargiulo Margene and Chuck Norton The Gettys Family Gayle Garrity In Memory of Michael Garrity Ann and Clarence Ohara Art Segal In Memory Of Marilynn Segal Franz Gerich Bonnie Jo Panagos Triangle Distributing Company Margarita and Robert Gomez Minna and Frank Patterson Yamaha Corporation of America Raejean C. Goodrich Carl B. Pearlston Beryl and Graham Gosling Marilyn and Jim Peters HEADLINER Timothy Gower Gwen and Gerry Pruitt Nancy and Nick Baker Alvena and Richard Graham Mr. -

The Osmonds the Proud One Mp3, Flac, Wma

The Osmonds The Proud One mp3, flac, wma DOWNLOAD LINKS (Clickable) Genre: Rock Album: The Proud One Country: UK Released: 1975 Style: Pop Rock MP3 version RAR size: 1757 mb FLAC version RAR size: 1591 mb WMA version RAR size: 1415 mb Rating: 4.1 Votes: 808 Other Formats: APE AHX TTA XM MOD VQF AAC Tracklist Hide Credits The Proud One A Arranged By – Michael LloydArranged By [Strings, Horns] – Gene PageProducer – Mike CurbWritten-By – Gaudio - Crewe* The Last Day Is Coming B Arranged By – Tommy OliverProducer – Alan Osmond, Michael LloydWritten-By – D. Osmond*, W. Osmond* Other versions Category Artist Title (Format) Label Category Country Year The Proud One (7", MGM Records, M 14791 The Osmonds M 14791 US 1975 Single) Kolob Records The Proud One (7", MGM Records, M 14791 The Osmonds M 14791 US 1975 Promo) Kolob Records The Proud One (7", New 2006 520 The Osmonds MGM Records 2006 520 1975 Single) Zealand The Proud One (7", MGM Records, 2006 520 The Osmonds 2006 520 UK 1975 Single, Blu) Kolob Records The Proud One (7", 2006 520 The Osmonds MGM Records 2006 520 Austria 1975 Single) Related Music albums to The Proud One by The Osmonds The Osmonds - Love Me For A Reason The Osmonds - Down By The Lazy River / He's The Light Of The World The Osmonds - One Way Ticket To Anywhere / Let Me In The Osmonds - The Very Best Of The Osmonds The Osmonds - Crazy Horses The Osmonds - Hold Her Tight The Osmonds - Having A Party The Osmonds & Jimmy Osmond, Toshiyuki Miyama & His The New Herd - The Osmonds Live In Tokyo The Osmonds - Live Donny Osmond Y Los Osmonds, El Pequeño Jimmy Osmond - We Got To Live Together / Trouble / I Got A Woman. -

Donny Osmond Returns to the Las Vegas Stage with First-Ever Solo Residency at Harrah's Las Vegas

Donny Osmond Returns To The Las Vegas Stage With First-Ever Solo Residency At Harrah's Las Vegas November 20, 2020 Tickets go on sale starting Tuesday, Nov. 24, 2020 Shows begin Tuesday, Aug. 31, 2021 LAS VEGAS, Nov. 20, 2020 /PRNewswire/ -- Legendary entertainer and music icon, Donny Osmond, today announced his return to Las Vegas and the Caesars Entertainment family with his first-ever solo multi-year residency inside Harrah's Showroom at Harrah's Las Vegas, opening Tuesday, Aug. 31, 2021. "Donny Osmond has achieved a lifetime of remarkable milestones as an entertainer, including countless memories with us during his 11-year run at Flamingo," said Caesars Entertainment Regional President Gary Selesner. "We're thrilled to welcome him to the stage at Harrah's Las Vegas next summer for an all-new show, and we look forward to sharing many more unforgettable moments with our guests and one of music's most beloved stars." In an unprecedented and history-making deal for Harrah's, Osmond's return to stage will be an exciting, energy-filled musical journey of his unparalleled life as one of the most recognized entertainers in the world. Guests can expect a party as he performs his timeless hits, shares stories of his greatest showstopping memories and introduces brand new music in a completely reimagined song and dance celebration. The announcement comes almost exactly one year after the curtains closed for the final time on his previous record-breaking 11-year residency at Flamingo Las Vegas. Fans can once again experience an unforgettable night with Donny Osmond – exclusively at Harrah's Las Vegas. -

100 Years: a Century of Song 1970S

100 Years: A Century of Song 1970s Page 130 | 100 Years: A Century of song 1970 25 Or 6 To 4 Everything Is Beautiful Lady D’Arbanville Chicago Ray Stevens Cat Stevens Abraham, Martin And John Farewell Is A Lonely Sound Leavin’ On A Jet Plane Marvin Gaye Jimmy Ruffin Peter Paul & Mary Ain’t No Mountain Gimme Dat Ding Let It Be High Enough The Pipkins The Beatles Diana Ross Give Me Just A Let’s Work Together All I Have To Do Is Dream Little More Time Canned Heat Bobbie Gentry Chairmen Of The Board Lola & Glen Campbell Goodbye Sam Hello The Kinks All Kinds Of Everything Samantha Love Grows (Where Dana Cliff Richard My Rosemary Grows) All Right Now Groovin’ With Mr Bloe Edison Lighthouse Free Mr Bloe Love Is Life Back Home Honey Come Back Hot Chocolate England World Cup Squad Glen Campbell Love Like A Man Ball Of Confusion House Of The Rising Sun Ten Years After (That’s What The Frijid Pink Love Of The World Is Today) I Don’t Believe In If Anymore Common People The Temptations Roger Whittaker Nicky Thomas Band Of Gold I Hear You Knocking Make It With You Freda Payne Dave Edmunds Bread Big Yellow Taxi I Want You Back Mama Told Me Joni Mitchell The Jackson Five (Not To Come) Black Night Three Dog Night I’ll Say Forever My Love Deep Purple Jimmy Ruffin Me And My Life Bridge Over Troubled Water The Tremeloes In The Summertime Simon & Garfunkel Mungo Jerry Melting Pot Can’t Help Falling In Love Blue Mink Indian Reservation Andy Williams Don Fardon Montego Bay Close To You Bobby Bloom Instant Karma The Carpenters John Lennon & Yoko Ono With My -

09.08.2010 / Kw 32

09.08.2010 / KW 32 Interpret Titel Punkte Label / Vertrieb Platz Tendenz Letzte Woche 2 Wochen Vor 3 Wochen Vor Veränderung Höchste Platzierung Wochen platziert Verkaufscharts 1 ● 1 1 2 YOLANDA BE COOL & DCUP We No Speak Americano 4005 Sweat It Out!/Superstar/Zebralution/Universal/UV 0 1 10 X 2 ● 2 2 4 PH ELECTRO Englishman In New York 2810 Yawa/Kontor New Media 0 2 5 - 3 ▲ 4 5 5 EDWARD MAYA FEAT. VIKA JIGULINA Stereo Love 2365 Universal/UV 1 3 34 X 4 ▼ 3 3 1 AVICII & SEBASTIEN DRUMS My Feelings For You 2233 Superstar/Zebralution -1 1 9 X 5 ▲ 14 44 - LASERKRAFT 3D Nein, Mann! 2052 We Play/Kontor New Media 9 5 3 - 6 ● 6 6 3 DAVID GUETTA & CHRIS WILLIS FEAT. FERGIE AND LMFAO Gettin' Over You 2014 Virgin/EMI 0 1 18 X 7 ▼ 5 4 10 JASPER FORKS River Flows In You (The Vocal Mixes) 1974 Kontor/Kontor New Media -2 4 5 X 8 ▲ 9 14 16 LADY GAGA Alejandro 1441 Streamline/KonLive/Interscope/Universal/UV 1 8 11 X 9 ▼ 8 8 8 LOONA Vamos A La Playa 1343 FutureBase/Kontor New Media -1 8 6 X 10 ● 10 9 9 KATY PERRY FEAT. SNOOP DOGG California Gurls 1299 Capitol/EMI 0 9 8 X 11 ● 11 13 15 SWEDISH HOUSE MAFIA FEAT. PHARRELL One (Your Name) 1156 EMI 0 10 13 X 12 ▲ 74 - - PICCO Venga 1068 Yawa/Kontor New Media 62 12 2 - 13 ▼ 7 7 6 COMICCON Komodo '10 1038 Zoo Digital/Zooland/Kontor New Media -6 5 7 - 14 ▼ 12 11 14 DARIUS & FINLAY FEAT. -

Voices in the Hall: Sam Bush (Part 1) Episode Transcript

VOICES IN THE HALL: SAM BUSH (PART 1) EPISODE TRANSCRIPT PETER COOPER Welcome to Voices in the Hall, presented by the Country Music Hall of Fame and Museum. I’m Peter Cooper. Today’s guest is a pioneer of New-grass music, Sam Bush. SAM BUSH When I first started playing, my dad had these fiddle albums. And I loved to listen to them. And then realized that one of the things I liked about them was the sound of the fiddle and the mandolin playing in unison together. And that’s when it occurred to me that I was trying on the mandolin to note it like a fiddle player notes. Then I discovered Bluegrass and the great players like Bill Monroe of course. You can specifically trace Bluegrass music to the origins. That it was started by Bill Monroe after he and his brother had a duet of mandolin and guitar for so many years, the Monroe Brothers. And then when he started his band, we're just fortunate that he was from the state of Kentucky, the Bluegrass State. And that's why they called them The Bluegrass Boys. And lo and behold we got Bluegrass music out of it. PETER COOPER It’s Voices in the Hall, with Sam Bush. “Callin’ Baton Rouge” – New Grass Revival (Best Of / Capitol) PETER COOPER “Callin’ Baton Rouge," by the New Grass Revival. That song was a prime influence on Garth Brooks, who later recorded it. Now, New Grass Revival’s founding member, Sam Bush, is a mandolin revolutionary whose virtuosity and broad- minded approach to music has changed a bunch of things for the better. -

Songs by Title Karaoke Night with the Patman

Songs By Title Karaoke Night with the Patman Title Versions Title Versions 10 Years 3 Libras Wasteland SC Perfect Circle SI 10,000 Maniacs 3 Of Hearts Because The Night SC Love Is Enough SC Candy Everybody Wants DK 30 Seconds To Mars More Than This SC Kill SC These Are The Days SC 311 Trouble Me SC All Mixed Up SC 100 Proof Aged In Soul Don't Tread On Me SC Somebody's Been Sleeping SC Down SC 10CC Love Song SC I'm Not In Love DK You Wouldn't Believe SC Things We Do For Love SC 38 Special 112 Back Where You Belong SI Come See Me SC Caught Up In You SC Dance With Me SC Hold On Loosely AH It's Over Now SC If I'd Been The One SC Only You SC Rockin' Onto The Night SC Peaches And Cream SC Second Chance SC U Already Know SC Teacher, Teacher SC 12 Gauge Wild Eyed Southern Boys SC Dunkie Butt SC 3LW 1910 Fruitgum Co. No More (Baby I'm A Do Right) SC 1, 2, 3 Redlight SC 3T Simon Says DK Anything SC 1975 Tease Me SC The Sound SI 4 Non Blondes 2 Live Crew What's Up DK Doo Wah Diddy SC 4 P.M. Me So Horny SC Lay Down Your Love SC We Want Some Pussy SC Sukiyaki DK 2 Pac 4 Runner California Love (Original Version) SC Ripples SC Changes SC That Was Him SC Thugz Mansion SC 42nd Street 20 Fingers 42nd Street Song SC Short Dick Man SC We're In The Money SC 3 Doors Down 5 Seconds Of Summer Away From The Sun SC Amnesia SI Be Like That SC She Looks So Perfect SI Behind Those Eyes SC 5 Stairsteps Duck & Run SC Ooh Child SC Here By Me CB 50 Cent Here Without You CB Disco Inferno SC Kryptonite SC If I Can't SC Let Me Go SC In Da Club HT Live For Today SC P.I.M.P. -

The Globalization of K-Pop: the Interplay of External and Internal Forces

THE GLOBALIZATION OF K-POP: THE INTERPLAY OF EXTERNAL AND INTERNAL FORCES Master Thesis presented by Hiu Yan Kong Furtwangen University MBA WS14/16 Matriculation Number 249536 May, 2016 Sworn Statement I hereby solemnly declare on my oath that the work presented has been carried out by me alone without any form of illicit assistance. All sources used have been fully quoted. (Signature, Date) Abstract This thesis aims to provide a comprehensive and systematic analysis about the growing popularity of Korean pop music (K-pop) worldwide in recent years. On one hand, the international expansion of K-pop can be understood as a result of the strategic planning and business execution that are created and carried out by the entertainment agencies. On the other hand, external circumstances such as the rise of social media also create a wide array of opportunities for K-pop to broaden its global appeal. The research explores the ways how the interplay between external circumstances and organizational strategies has jointly contributed to the global circulation of K-pop. The research starts with providing a general descriptive overview of K-pop. Following that, quantitative methods are applied to measure and assess the international recognition and global spread of K-pop. Next, a systematic approach is used to identify and analyze factors and forces that have important influences and implications on K-pop’s globalization. The analysis is carried out based on three levels of business environment which are macro, operating, and internal level. PEST analysis is applied to identify critical macro-environmental factors including political, economic, socio-cultural, and technological.