Savus and Adsalluta

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

By Bus Around the Julian Alps

2019 BY BUS AROUND THE JULIAN ALPS BLED BOHINJ BRDA THE SOČA VALLEY GORJE KRANJSKA GORA JESENICE rAdovljicA žirovnicA 1 2 INTRO 7 BLED, RADOVLJICA, ŽIROVNICA 8 1 CHARMING VILLAGE CENTRES 10 2 BEES, HONEY AND BEEKEEPERS 14 3 COUNTRYSIDE STORIES 18 4 PANORAMIC ROAD TO TRŽIČ 20 BLED 22 5 BLED SHUTTLE BUS – BLUE LINE 24 6 BLED SHUTTLE BUS – GREEN LINE 26 BOHINJ 28 7 FROM THE VALLEY TO THE MOUNTAINS 30 8 CAR-FREE BOHINJ LAKE 32 9 FOR BOHINJ IN BLOOM 34 10 PARK AND RIDE 36 11 GOING TO SORIŠKA PLANINA TO ENJOY THE VIEW 38 12 HOP-ON HOP-OFF POKLJUKA 40 13 THE SAVICA WATERFALL 42 BRDA 44 14 BRDA 46 THE SOČA VALLEY 48 15 HOP-ON HOP-OFF KOBARID – RED LINE 50 16 HOP-ON HOP-OFF KOBARID – ORANGE LINE 52 17 HOP-ON HOP-OFF KOBARID – GREEN LINE 54 18 HOP-ON HOP-OFF KOBARID – PURPLE LINE 56 19 HOP-ON HOP-OFF KOBARID – BLUE LINE 58 20 THE TOLMINKA RIVER GORGE 62 21 JAVORCA, MEMORIAL CHURCH IN THE TOLMINKA RIVER VALLEY 64 22 OVER PREDEL 66 23 OVER VRŠIČ 68 KRANJSKA GORA 72 24 KRANJSKA GORA 74 Period during which transport is provided Price of tickets Bicycle transportation Guided tours 3 I 4 ALPS A JULIAN Julian Alps Triglav National Park 5 6 SLOVEniA The Julian Alps and the Triglav National Park are protected by the UNESCO Man and the Biosphere Programme because the Julian Alps are a treasury of natural and cultural richness. The Julian Alps community is now more interconnected than ever before and we are creating a new sustainable future of green tourism as the opportunity for preserving cultural and natural assets of this fragile environment, where the balance between biodiversity and lifestyle has been preserved by our ancestors for centuries. -

Königl, Bayer Akademie Der Wissenschaften

ZOBODAT - www.zobodat.at Zoologisch-Botanische Datenbank/Zoological-Botanical Database Digitale Literatur/Digital Literature Zeitschrift/Journal: Sitzungsberichte der philosophisch-philologische Classe der Bayerischen Akademie der Wissenschaften München Jahr/Year: 1865 Band/Volume: 1865-1 Autor(en)/Author(s): Glück Christian Wilhelm von Artikel/Article: Die Erklärung des Rénos, Moinos und Mogontiâcon, der gallischen Namen der Flüsse Rein und Main und der Stadt Mainz 1-27 S itzim g ’sb erich te der königl, bayer Akademie der Wissenschaften zu München. Jahrgang 1865. Band I. M ü n c h e n . Druck von F. Straub (Wittelsbacherplatz 3). 1865. In Commission bei G. Franz. Sitzungsberichte der königl, bayer. Akademie der Wissenschaften. Philosophisch - philologische Classe. Sitzung vom 7. Januar 1865. Herr C hrist berichtet über eine Abhandlung des Herrn VV. G lü ck , welche die Classe hiermit dem Drucke übergibt: „Die Erklärung des Renos, Moinos und Mogon- tiacon, der gallischen Namen der Flüsse Rein und Main und der Stadt Mainz.“ Der Rein heisst bekanntlich bei den Griechen ‘Prjvog, bei den Römern Rhfrnus. Der gallische Name lautet Rönos, früher Renas1). Das Keltische hat kein gehauch- 1) Die alte Nominativendung as der auf a ausgehnden männ lichen Stämme findet sich noch in den ältesten Denkmälern der irischen Sprache, den Ogaminschriften. (Hierüber s. unsere Schrift: Der deutsche Name Brachio nebst einer Antwort auf einen Angriff Holzmanns. München 1864. 10. S. 2. Anm.) Doch kommt auch dort die Endung os vor (s. Beiträge zur vergleich. Sprachforsch. I, 448). In den in gallischer Sprache geschriebenen Inschriften (ebend. III, [1865. I. 1.] 1 2 Sitzung der philos.-philol. Classe vom 7. -

Emerald Cycling Trails

CYCLING GUIDE Austria Italia Slovenia W M W O W .C . A BI RI Emerald KE-ALPEAD Cycling Trails GUIDE CYCLING GUIDE CYCLING GUIDE 3 Content Emerald Cycling Trails Circular cycling route Only few cycling destinations provide I. 1 Tolmin–Nova Gorica 4 such a diverse landscape on such a small area. Combined with the turbulent history I. 2 Gorizia–Cividale del Friuli 6 and hospitality of the local population, I. 3 Cividale del Friuli–Tolmin 8 this destination provides ideal conditions for wonderful cycling holidays. Travelling by bicycle gives you a chance to experi- Connecting tours ence different landscapes every day since II. 1 Kolovrat 10 you may start your tour in the very heart II. 2 Dobrovo–Castelmonte 11 of the Julian Alps and end it by the Adriatic Sea. Alpine region with steep mountains, deep valleys and wonderful emerald rivers like the emerald II. 3 Around Kanin 12 beauty Soča (Isonzo), mountain ridges and western slopes which slowly II. 4 Breginjski kot 14 descend into the lowland of the Natisone (Nadiža) Valleys on one side, II. 5 Čepovan valley & Trnovo forest 15 and the numerous plateaus with splendid views or vineyards of Brda, Collio and the Colli Orientali del Friuli region on the other. Cycling tours Familiarization tours are routed across the Slovenian and Italian territory and allow cyclists to III. 1 Tribil Superiore in Natisone valleys 16 try and compare typical Slovenian and Italian dishes and wines in the same day, or to visit wonderful historical cities like Cividale del Friuli which III. 2 Bovec 17 was inscribed on the UNESCO World Heritage list. -

Heavy Metals in the Sediment of Sava River, Slovenia

GEOLOGIJA 46/2, 263–272, Ljubljana 2003 doi:10.5474/geologija.2003.023 Heavy metals in the sediment of Sava River, Slovenia Te‘ke kovine v sedimentih reke Save, Slovenija Jo‘e KOTNIK1, Milena HORVAT1, Radmila MILA^I^1, Janez [^AN^AR1, Vesna FAJON1 & Andrej KRI@ANOVSKI2 1 Jozef Stefan Institute, Department of Environmental Sciences, Jamova 39, 1000 Ljubljana, Slovenia 2 Sava Power Generation Company, Hajdrihova 2. 1000 Ljubljana, Slovenia E-mail: [email protected] Key words: heavy metals, acetic acid extraction, normalization, river sediments, Slo- venia Klju~ne besede: te‘ke kovine, ekstrakcija z ocetno kislino, normalizacija, re~ni sedi- menti, Slovenija Abstract The Sava River is the longest river in Slovenia and it has been a subject of heavy pollution in the past ([tern & Förstner 1976). In order to determine the anthropogenic contribution of selected metals (Cd, Co, Cr, Cu, Fe, Hg, Ni, Pb and Zn) to background levels, concentrations of these metals were measured in sediments at several downstream locations. An extracting procedure using 25% (v/v) acetic acid was applied for estimation of the extent of contamination with heavy metals originating from anthropogenic activities. In addition, a normalization technique was used to determine background, naturally enriched and contamination levels. Aluminum was found to be good normalizer for most of the measured elements. The results suggest that an anthropogenic contamination of certain metal is not necessarily connected to easily extractable fraction in 25% acetic acid. As a consequence of anthropogenic activities the elevated levels of all measured elements were found near Acroni Jesenice steelworks and at some locations downflow from biggest cities. -

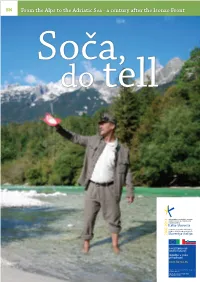

From the Alps to the Adriatic

EN From the Alps to the Adriatic Sea - a century after the Isonzo Front Soča, do tell “Alone alone alone I have to be in eternity self and self in eternity discover my lumnious feathers into afar space release and peace from beyond land in self grip.” Srečko Kosovel Dear travellers Have you ever embraced the Alps and the Adriatic with by the Walk of Peace from the Alps to the Adriatic Sea that a single view? Have you ever strolled along the emerald runs across green and diverse landscape – past picturesque Soča River from its lively source in Triglav National Park towns, out-of-the-way villages and open fireplaces where to its indolent mouth in the nature reserve in the Bay of good stories abound. Trieste? Experience the bonds that link Italy and Slove- nia on the Walk of Peace. Spend a weekend with a knowledgeable guide, by yourself or in a group and see the sites by car, on foot or by bicycle. This is where the Great War cut fiercely into serenity a century Tourism experience providers have come together in the T- ago. Upon the centenary of the Isonzo Front, we remember lab cross-border network and together created new ideas for the hundreds of thousands of men and boys in the trenches your short break, all of which can be found in the brochure and on ramparts that they built with their own hands. Did entitled Soča, Do Tell. you know that their courageous wives who worked in the rear sometimes packed clothing in the large grenades instead of Welcome to the Walk of Peace! Feel the boundless experi- explosives as a way of resistance? ences and freedom, spread your wings among the vistas of the mountains and the sea, let yourself be pampered by the Today, the historic heritage of European importance is linked hospitality of the locals. -

PRILOGA 1 Seznam Vodnih Teles, Imena in Šifre, Opis Glede Na Uporabljena Merila Za Njihovo Določitev in Razvrstitev Naravnih Vodnih Teles V Tip

Stran 4162 / Št. 32 / 29. 4. 2011 Uradni list Republike Slovenije P R A V I L N I K o spremembah in dopolnitvah Pravilnika o določitvi in razvrstitvi vodnih teles površinskih voda 1. člen V Pravilniku o določitvi in razvrstitvi vodnih teles površin- skih voda (Uradni list RS, št. 63/05 in 26/06) se v 1. členu druga alinea spremeni tako, da se glasi: »– umetna vodna telesa, močno preoblikovana vodna telesa in kandidati za močno preoblikovana vodna telesa ter«. 2. člen V tretjem odstavku 6. člena se v drugi alinei za besedo »vplive« doda beseda »na«. 3. člen Priloga 1 se nadomesti z novo prilogo 1, ki je kot priloga 1 sestavni del tega pravilnika. Priloga 4 se nadomesti z novo prilogo 4, ki je kot priloga 2 sestavni del tega pravilnika. 4. člen Ta pravilnik začne veljati petnajsti dan po objavi v Ura- dnem listu Republike Slovenije. Št. 0071-316/2010 Ljubljana, dne 22. aprila 2011 EVA 2010-2511-0142 dr. Roko Žarnić l.r. Minister za okolje in prostor PRILOGA 1 »PRILOGA 1 Seznam vodnih teles, imena in šifre, opis glede na uporabljena merila za njihovo določitev in razvrstitev naravnih vodnih teles v tip Merila, uporabljena za določitev vodnega telesa Ime Zap. Povodje Površinska Razvrstitev Tip Pomembna Presihanje Pomembna Pomembno Šifra vodnega Vrsta št. ali porečje voda v tip hidro- antropogena različno telesa morfološka fizična stanje sprememba sprememba 1 SI1118VT Sava Radovna VT Radovna V 4SA x x x VT Sava Sava 2 SI111VT5 Sava izvir – V 4SA x x x Dolinka Hrušica MPVT Sava 3 SI111VT7 Sava zadrževalnik MPVT x Dolinka HE Moste Blejsko VTJ Blejsko 4 SI1128VT Sava J A2 x jezero jezero VTJ Bohinjsko 5 SI112VT3 Sava Bohinjsko J A1 x jezero jezero VT Sava Sava 6 SI11 2VT7 Sava Sveti Janez V 4SA x x Bohinjka – Jezernica VT Sava Jezernica Sava 7 SI1 1 2VT9 Sava – sotočje V 4SA x x Bohinjka s Savo Dolinko Uradni list Republike Slovenije Št. -

JULIAN ALPS TRIGLAV NATIONAL PARK 2The Julian Alps

1 JULIAN ALPS TRIGLAV NATIONAL PARK www.slovenia.info 2The Julian Alps The Julian Alps are the southeast- ernmost part of the Alpine arc and at the same time the mountain range that marks the border between Slo- venia and Italy. They are usually divided into the East- ern and Western Julian Alps. The East- ern Julian Alps, which make up approx- imately three-quarters of the range and cover an area of 1,542 km2, lie entirely on the Slovenian side of the border and are the largest and highest Alpine range in Slovenia. The highest peak is Triglav (2,864 metres), but there are more than 150 other peaks over 2,000 metres high. The emerald river Soča rises on one side of the Julian Alps, in the Primorska re- gion; the two headwaters of the river Sava – the Sava Dolinka and the Sava Bohinjka – rise on the other side, in the Gorenjska region. The Julian Alps – the kingdom of Zlatorog According to an ancient legend a white chamois with golden horns lived in the mountains. The people of the area named him Zlatorog, or “Goldhorn”. He guarded the treasures of nature. One day a greedy hunter set off into the mountains and, ignoring the warnings, tracked down Zlatorog and shot him. Blood ran from his wounds Chamois The Triglav rose and fell to the ground. Where it landed, a miraculous plant, the Triglav rose, sprang up. Zlatorog ate the flowers of this plant and its magical healing powers made him invulnerable. At the same time, however, he was saddened by the greed of human beings. -

(PAF) for NATURA 2000 in SLOVENIA

PRIORITISED ACTION FRAMEWORK (PAF) FOR NATURA 2000 in SLOVENIA pursuant to Article 8 of Council Directive 92/43/EEC on the conservation of natural habitats and of wild fauna and flora (the Habitats Directive) for the Multiannual Financial Framework period 2021 – 2027 Contact address: Ministry of the Environment and Spatial Planning Dunajska 48 SI- 1000 Ljubljana Slovenia [email protected] PAF SI 2019 A. Introduction A.1 General introduction Prioritised action frameworks (PAFs) are strategic multiannual planning tools, aimed at providing a comprehensive overview of the measures that are needed to implement the EU-wide Natura 2000 network and its associated green infrastructure, specifying the financing needs for these measures and linking them to the corresponding EU funding programmes. In line with the objectives of the EU Habitats Directive1 on which the Natura 2000 network is based, the measures to be identified in the PAFs shall mainly be designed "to maintain and restore, at a favourable conservation status, natural habitats and species of EU importance, whilst taking account of economic, social and cultural requirements and regional and local characteristics". The legal basis for the PAF is Article 8 (1) of the Habitats Directive2, which requires Member States to send, as appropriate, to the Commission their estimates relating to the European Union co-financing which they consider necessary to meet their following obligations in relation to Natura 2000: to establish the necessary conservation measures involving, if need be, appropriate management plans specifically designed for the sites or integrated into other development plans, to establish appropriate statutory, administrative or contractual measures which correspond to the ecological requirements of the natural habitat types in Annex I and the species in Annex II present on the sites. -

Monitoring Kakovosti Površinskih Vodotokov V Sloveniji V Letu 2006

REPUBLIKA SLOVENIJA MINISTRSTVO ZA OKOLJE IN PROSTOR AGENCIJA REPUBLIKE SLOVENIJE ZA OKOLJE MONITORING KAKOVOSTI POVRŠINSKIH VODOTOKOV V SLOVENIJI V LETU 2006 Ljubljana, junij 2008 REPUBLIKA SLOVENIJA MINISTRSTVO ZA OKOLJE IN PROSTOR AGENCIJA REPUBLIKE SLOVENIJE ZA OKOLJE MONITORING KAKOVOSTI POVRŠINSKIH VODOTOKOV V SLOVENIJI V LETU 2006 Nosilka naloge: mag. Irena Cvitani č Poro čilo pripravili: mag. Irena Cvitani č in Edita Sodja Sodelavke: mag. Mojca Dobnikar Tehovnik, Špela Ambroži č, dr. Jasna Grbovi ć, Brigita Jesenovec, Andreja Kolenc, mag. Špela Kozak Legiša, mag. Polona Mihorko, Bernarda Rotar Karte pripravila: Petra Krsnik mag. Mojca Dobnikar Tehovnik dr. Silvo Žlebir VODJA SEKTORJA GENERALNI DIREKTOR Monitoring kakovosti površinskih vodotokov v Sloveniji v letu 2006 Podatki, objavljeni v Poro čilu o kakovosti površinskih vodotokov v Sloveniji v letu 2006, so rezultat kontroliranih meritev v mreži za spremljanje kakovosti voda. Poro čilo in podatki so zaš čiteni po dolo čilih avtorskega prava, tisk in uporaba podatkov sta dovoljena le v obliki izvle čkov z navedbo vira. ISSN 1855 – 0320 Deskriptorji: Slovenija, površinski vodotoki, kakovost, onesnaženje, vzor čenje, ocena stanja Descriptors: Slovenia, rivers, quality, pollution, sampling, quality status Monitoring kakovosti površinskih vodotokov v Sloveniji v letu 2006 KAZALO VSEBINE 1 POVZETEK REZULTATOV V LETU 2006 ........................................................................................ 1 2 UVOD ....................................................................................................................................... -

Stran 9102 / Št. 59 / 7. 9. 2018 Uradni List Republike Slovenije

Stran 9102 / Št. 59 / 7. 9. 2018 Uradni list Republike Slovenije Priloga: SEZNAM REFERENČNIH MERILNIH POSTAJ REFERENČNE NAZIV MERILNE GKY (D48) GKX (D48) VRSTA MERILNE POSTAJE METEOROLOŠ POSTAJE KE VELIČINE Hidrološka merilna postaja - Ajdovščina I - Hubelj 415406,25 83869,56 tekoče površinske vode Babno Polje 464897 55758 Meteorološka merilna postaja P,TH Bača pri Modreju - Hidrološka merilna postaja - 405797,61 113109,92 Bača tekoče površinske vode Hidrološka merilna postaja - Benica 616226,325 152574,7 podzemne vode Hidrološka merilna postaja - Bevke 451347,5 92350,5 podzemne vode Bilje 393592 84402 Meteorološka merilna postaja P,TH,S,V Hidrološka merilna postaja - Bistra I - Bistra 449141,3 89724,4 tekoče površinske vode Bišče - Kamniška Hidrološka merilna postaja - 470672,1 106707,2 Bistrica tekoče površinske vode Hidrološka merilna postaja - Blate - Rakitnica 480493 61182,2 tekoče površinske vode Hidrološka merilna postaja - Bled 432315,6 137784,9 podzemne vode Blegoš 429451 114110 Meteorološka merilna postaja P,TH Blejski most - Sava Hidrološka merilna postaja - 433786,9 136303 Dolinka tekoče površinske vode Bodešče - Sava Hidrološka merilna postaja - 434317,5 133446,9 Bohinjka tekoče površinske vode Bohinjska Bistrica - Hidrološka merilna postaja - 419448,8 126032 Bistrica tekoče površinske vode Bohinjska Češnjica 418876 128334 Meteorološka merilna postaja P,TH Boja Zarja Tržaški Oceanografska merilna 385747 52339 zaliv postaja Oceanografska merilna Boja Zora Debeli rtič 396383 52348 postaja Borovnica - Hidrološka merilna postaja -

Manuscript Title in Title Case

The Radioactivity of River Sediments in Slovenia as a Consequence of Global and Local Contamination Denis Glavič-Cindro, Matjaž Korun "Jožef Stefan" Institute Jamova cesta 39, 1000 Ljubljana, Slovenia [email protected], [email protected] Milko Križman Slovenian Nuclear Safety Administration, Železna cesta 16 1000 Ljubljana, Slovenia [email protected] ABSTRACT In this article we discuss the activity concentrations of natural and man-made radionuclides in moving and bottom river sediments. The moving sediments were collected during a six-week period, while the bottom sediments were obtained by grab sampling. The concentrations of the radioisotopes were systematically larger in the moving sediments than in the bottom sediments. The contamination of the sediments with man-made radionuclides Cs-137 and I-131 was observed, as well as enhanced concentrations of natural radionuclides. Cs-137 was identified in all the samples; I-131 was identified at the locations where the influence of discharges from hospitals was expected, as well as at locations where there is no direct influence of these discharges. From a comparison between the concentrations of radioisotopes of the uranium and thorium decay series in different samples, the influence of industrial activities was identified. Elevated concentrations of U-238, Ra-226 and Ra-228 identified the probable influences of coal, lead and uranium-ore mining and the processing of monazite in the production of TiO2. 1 INTRODUCTION The Euratom Treaty [1] requires all the Member States of the European Union to monitor continuously the level of radioactivity in the air, water and soil. Whereas monitoring the air and soil is relatively easy, by pumping air through aerosol filters and by measuring the dose rate above the soil, the continuous monitoring of water is more demanding. -

Protocol Amending the Agreement on Government Procurement

PROTOCOL AMENDING THE AGREEMENT ON GOVERNMENT PROCUREMENT PROTOCOLE PORTANT AMENDEMENT DE L'ACCORD SUR LES MARCHÉS PUBLICS PROTOCOLO POR EL QUE SE MODIFICA EL ACUERDO SOBRE CONTRATACIÓN PÚBLICA WORLD TRADE ORGANIZATION ORGANISATION MONDIALE DU COMMERCE ORGANIZACIÓN MUNDIAL DEL COMERCIO Geneva 30 March 2012 - 1 - PROTOCOL AMENDING THE AGREEMENT ON GOVERNMENT PROCUREMENT The Parties to the Agreement on Government Procurement, done at Marrakesh on 15 April 1994, (hereinafter referred to as "the 1994 Agreement"), Having undertaken further negotiations pursuant to Article XXIV:7(b) and (c) of the 1994 Agreement; Hereby agree as follows: 1. The Preamble, Articles I through XXIV, and Appendices to the 1994 Agreement shall be deleted and replaced by the provisions as set forth in the Annex hereto. 2. This Protocol shall be open for acceptance by the Parties to the 1994 Agreement. 3. This Protocol shall enter into force for those Parties to the 1994 Agreement that have deposited their respective instruments of acceptance of this Protocol, on the 30th day following such deposit by two thirds of the Parties to the 1994 Agreement. Thereafter this Protocol shall enter into force for each Party to the 1994 Agreement which has deposited its instrument of acceptance of this Protocol, on the 30th day following the date of such deposit. 4. This Protocol shall be deposited with the Director-General of the WTO, who shall promptly furnish to each Party to the 1994 Agreement a certified true copy of this Protocol, and a notification of each acceptance thereof. 5. This Protocol shall be registered in accordance with the provisions of Article 102 of the Charter of the United Nations.