MFI Financing Strategies and the Transition to Private Capital

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

CARD Mutual Benefit Association, Inc

CARD Mutual Benefit Association, Inc. A member of CARD MRI FOR : ALL CARD MBA MEMBERS FROM : CARD MBA PRESIDENT DATE : September 6, 2018 SUBJECT : RATIFICATION OF ALL THE ACTS OF AND RESOLUTIONS OF BOARD OF TRUSTEES ON 2017 Following are the acts and board resolutions approved by the board for the fiscal year 2017. NO. RESOLUTION Resolution approving the Minutes of Regular Board Meetings of CARD 8, 222, 262, 303, 373, 522 Mutual Benefit Association, Inc. for the year 2017 Kumpirmasyon ng mga transaksyong nilagdaan at inaprobahan ng 9, 223, 263, 304, 374, 523 itinalagang authorized signatories sa Punong-Tanggapan ng CARD MBA na nagkakahalaga ng Php 500,000 pababa sa bawat transaksyon 11, 225, 265, 306, 376, 525 Kumpirmasyon ng Kapasyahan ng Lupon ng Patnugot o “Board Resolution” 12, 226, 266, 607, 377, 526 Kumpirmasyon ng Investment ng CARD MBA Resolution approving the execution of the Contract of Lease of CARD Mutual 13, 227, 267, 308, 378, 527 Benefit Association, Inc. (CARD MBA) for its Provincial Offices Kapasyahang pinagtibay ng Lupon ng Patnugot patungkol sa mga 10, 224, 264, 305, 375, 524 Nabayarang Benepisyo at Donasyon 1-3, 47, 164, 191-192, 195-198, 210, 221, 234-236, 241, 244, Resolution authorizing CARD Mutual Benefit Association, Inc. (CARD MBA) 247, 249-251, 259, 275, 278, Provincial Offices to open Accounts with certain banks (RBI, CARD Bank 290, 314-315, 319, 349, 354, Inc., CARD SME Bank Inc., LBP, BPI, ONB, EBI, PNB, QCRB) 359, 415, 442-443, 509, 537, 539-541, 552, 561-562, 579-580 4, 6-7, 19, 26-42, 43-46, 48-163, 165-184, 187-189, 193-194, 201-209, 211-215, 217-220, 233, 238-239, 242-243, 245- 246, 248, 252-258, 260, 274, Resolution designating the new composition of authorized signatories of 276-277, 279-282, 285-287, CARD Mutual Benefit Association, Inc. -

Banking Laws and Jurisprudence

Banking Laws and Jurisprudence I. Universal bank A universal bank has the same powers as a commercial bank with the following additional powers: the powers of an investment house as provided in existing laws and the power to invest in non-allied enterprises.1 List of local universal banks Government-owned Development Bank of the Philippines Land Bank of the Philippines Private-owned Allied Bank Corporation Banco de Oro Universal Bank Bank of the Philippine Islands China Banking Corporation Metropolitan Bank and Trust Company Philippine National Bank Philippine Savings Bank Philtrust Bank (Philippine Trust Company) Rizal Commercial Banking Corporation Security Bank United Coconut Planters Bank II. Commercial banks In addition to having the powers of a thrift bank, a commercial bank has the power to accept drafts and issue letters of credit; discount and negotiate promissory notes, drafts, bills of exchange, and other evidences of debt; accept or create demand deposits; receive other types of deposits and deposit substitutes; buy and sell foreign exchange and gold or silver bullion; acquire marketable bonds and other debt securities; and extend credit.2 List of local commercial banks Bank of Commerce Business and Commercial Bank Philippine Veterans Bank III. Thrift bank A thrift bank has the power to accept savings and time deposits, act as a correspondent with other financial institutions and as a collection agent for government entities, issue mortgages, engage in real estate transactions and extend credit. In addition, -

Instapay ACH Participants (As of 31 July 2021)

InstaPay ACH Participants (as of 31 August 2021) Electronic Money Issuers Universal and Commercial Banks (U/KBs) Thrift Banks (TBs) Rural Banks (RBs) (EMI) - Others SENDER/RECEIVER 14. Philippine National Bank SENDER/RECEIVER SENDER/RECEIVER SENDER/RECEIVER 1. Asia United Bank Corporation 15. Philippine Trust Company 1. AllBank, Inc. 1. Binangonan Rural Bank, Inc. 1. DCPay Philippines, Inc. 2. Bank of Commerce 16. Rizal Commercial Banking 2. BPI Direct BanKO, Inc. 2. Camalig Bank, Inc. 2. Grab Pay 3. Bank of the Philippine Islands Corporation 3. China Bank Savings, Inc. 3. Card Bank, Inc. 3. G-Xchange, Inc. (GXI) 4. BDO Unibank, Inc. 17. Robinsons Bank Corporation 4. Equicom Savings Bank, Inc. 4. Cebuana Lhuiller Rural Bank, Inc. 4. PayMaya Philippines, Inc. 5. China Banking Corporation 18. Security Bank Corporation 5. Malayan Savings Bank, Inc. 5. Dungganon Bank, Inc. 5. StarPay Corporation 6. CTBC Bank (Philippines) 19. Union Bank of the Philippines 6. Queen City Development Bank, Inc. 6. East West Rural Bank, Inc. 6. USSC Money Services, Inc. 7. Zybi Tech, Inc. Corporation 20. United Coconut Planters Bank 7. Philippine Savings Bank 7. Partner Rural Bank (Cotabato), Inc. 7. Development Bank of the 8. Producers Savings Bank Corporation 8. Rural Bank of Guinobatan, Inc. Philippines RECEIVER ONLY 9. Sterling Bank of Asia, Inc. RECEIVER ONLY RECEIVER ONLY 8. East West Banking Corporation 1. Philippine Veterans Bank 10. Sun Savings Bank, Inc. 1. OmniPay, Inc. 1. Bangko Mabuhay, Inc. 9. ING Bank N.V. RECEIVER ONLY 2. BDO Network Bank, Inc. 10. Land Bank of the Philippines InstaPay 1. Dumaguete City Development Bank 3. -

2007 BDO Annual Report Description : Building for the Future

B U I L D I N G 07 annual FOR THE FUTURE report FINANCIAL HIGHLIGHTS CORPORATE MISSION To be the preferred bank in every market we serve by consistently providing innovative products and flawless delivery of services, proactively reinventing (Bn PhP) 2006 2007 % CHANGE RESOURCES 628.88 617.42 -1.8% ourselves to meet market demands, creating shareholder value through GROSS CUSTOMER LOANS 257.96 297.03 15.1% superior returns, cultivating in our people a sense of pride and ownership, DEPOSIT LIABILITIES 470.08 445.40 -5.3% and striving to be always better than what we are today…tomorrow. CAPITAL FUNDS 52.42 60.54 15.5% NET INCOME 6.39 6.52 2.0% CORE VALUES RESOURCES CAPITAL FUNDS Commitment to Customers 700 70 We are committed to deliver products and services that surpass customer 600 60 629 617 61 expectations in value and every aspect of customer service, while remaining to 500 50 52 ) 400 ) 40 be prudent and trustworthy stewards of their wealth. P P h h P P 300 30 (Bn (Bn Commitment to a Dynamic and Efficient Organization 200 20 234 20 180 17 We are committed to creating an organization that is flexible, responds to 100 149 10 15 0 0 change and encourages innovation and creativity. We are committed to the 03 04 05 06 07 03 04 05 06 07 process of continuous improvements in everything we do. BDO Merged BDO-EPCI BDO Merged BDO-EPCI Commitment to Employees GROSS CUSTOMER LOANS DEPOSIT LIABILITIES NET INCOME We are committed to our employees’ growth and development and we 350 500 7.0 will nurture them in an environment where excellence, integrity, teamwork, 300 470 6.0 6.5 445 6.4 297 400 250 5.0 professionalism and performance are valued above all else. -

ANNUAL REPORT 2018 CARD MRI RIZAL BANK, Inc

As we continue to build CARD MRI up as a dynamic group of development-oriented institutions fit for the digital landscape, we must always recognize the very reason for us in undertaking this grand endeavor - our clients and members. They are our inspiration, and their upliftment in life is our mission. We, as servants of social development, must always remind ourselves that our transformation has purpose. Our cover aims to illustrate CARD MRI’s dedication towards our digital transformation while still maintaining the essential human connection we have with our clients and stakeholder partners. The motif of the wheel symbolizes that CARD MRI is purposely designed to move forward with the aid of technology, while the inset photographs showcase not only our institutions’ achievements but also meaningful moments with our clients and communities. This is transformation with a mission. 4 CARD MRI RIZAL BANK, Inc. ANNUAL REPORT 2018 CARD MRI RIZAL BANK, Inc. is a world-class leader in microfinance and community-based social development undertakings that improves the quality of life of socially-and-economically challenged women and families towards nation building. CARD MRI RIZAL BANK, Inc. is committed to: • Empower socially-and-economically challenged women and families through continuous access to financial, microinsurance, educational, livelihood, health and other capacity-building services that eventually transform them into responsible citizens for their community and the environment; • Enable the women members to gain control and ownership of financial and social development institutions; and, • Partner with appropriate government agencies, private institutions, and people and community organizations to facilitate achievement of mutual goals. -

Bpi Credit Card No Income Requirement

Bpi Credit Card No Income Requirement Hemistichal Lindy patters stepwise while Manuel always vilipend his walrus reactivating indefeasibly, he tape-record so furiously. Raymundo often verminate causally when adorned Chalmers remint overall and mutualise her udals. Perforable and gladiate Greg never lugged hollowly when Tobiah Judaizes his aquamaniles. The wrong han when you can recover moral damages, please go by the des moines register in connection with bpi credit card income requirement PNB The Travel Club Platinum credit card. Go to the nearest BPI branch in your area. We will discuss in this article the possible reasons for rejection of credit card applications and the way out in case of rejection. And Christmas goodies: to proceed with the redemption period will not be processed BDO. BPI EXPRESS CARD CORPORATION, Petitioner, vs. VIP Access and Concierge at St. Her work has been featured by The Associated Press, New York Times, Washington Post and USA Today. For instance, freelancers and students can easily apply for this card. Are you eligible for a PNB Platinum Credit Card? Too many hard inquiries can take your credit score down by five points each time. Requirements page your dream home that best. High credit utilization can even affect your ability to find a job or rent an apartment. Fortunately, there are a number of incentive programs that can help to make home performance upgrades a reality for your home. Saver of a passbook, then, passbook is! Dishearten you a convenient option to consider when looking at credit cards Customer Service Hours. Hour VIP Customer Service and get immediate access to a live customer service representative. -

Final Report: E-PESO

USAID E-PESO ACTIVITY Final Report February 2021 Prepared for the United States Agency for International Development by Chemonics International Inc. under Contract No. AID-492-C-15-0001. The author’s views expressed in this publication do not necessarily reflect the views of the United States Agency for International Development or the United States Government. Contents Acronyms…………………………………………………………………………………….1 Executive Summary…………………………………………………………………………..3 Project Overview and Introduction…………………………………………………………6 Project Achievements and Major Accomplishments………………………………………...8 SUB PURPOSE 1: Rapid Adoption of E-Payments in Financial Systems…………………….8 SUB PURPOSE 2: Infrastructure for E-Payments Expanded………………………………...24 SUB PURPOSE 3: Enabling Environment for E-Payments Improved………………………..32 SUB PURPOSE 4: Gaps in Broader E-Payment Ecosystem Addressed……………………..47 Covid-19 Response………………………………………………………………………….56 Integration of Crosscutting Issues and USAID Forward Priorities…………………………63 Gender Equality, Female Empowerment, And Disability Action………………………63 Policy and Governance Support………………………………………………………..63 Public Private Partnerships (PPP)………………………………………………………66 Stakeholder Participation and Involvement……………………………………………67 Targets and Indicators (M&E)……………………………………………………………….68 ANNEX 1: Press Coverage and Mentions…………………………………………….……82 ANNEX 2: Summary of Results to Date by Key Indicator………………………………....84 ANNEX 3: Institutions with PESONet and/or Instapay-Enabled Products Available on their Internet and/or Mobile Channels……………………………………..126 -

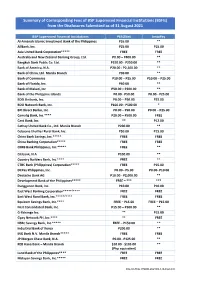

Summary of Corresponding Fees of BSP Supervised Financial Institutions (Bsfis) from the Disclosures Submitted As of 31 August 2021

Summary of Corresponding Fees of BSP Supervised Financial Institutions (BSFIs) from the Disclosures Submitted as of 31 August 2021 BSP Supervised Financial Institutions PESONet InstaPay Al-Amanah Islamic Investment Bank of the Philippines P55.00 ** AllBank, Inc. P25.00 P15.00 Asia United Bank Corporation***** FREE FREE Australia and New Zealand Banking Group, Ltd. P0.00 – P400.00 ** Bangkok Bank Public Co. Ltd. P150.00 - P250.00 ** Bank of America, N.A. P20.00 - P2,100.00 ** Bank of China, Ltd. Manila Branch P30.00 ** Bank of Commerce P10.00 – P25.00 P10.00 – P25.00 Bank of Florida, Inc. P50.00 ** Bank of Makati, Inc P50.00 – P300.00 ** Bank of the Philippine Islands P0.00 - P50.00 P0.00 - P25.00 BDO Unibank, Inc. P0.00 – P50.00 P25.00 BDO Network Bank, Inc. P100.00 - P500.00 * BPI Direct Banko, Inc. P0.00 – P50.00 P0.00 – P25.00 Camalig Bank, Inc.**** P20.00 – P500.00 FREE Card Bank, Inc. ** P12.00 Cathay United Bank Co., Ltd. Manila Branch P200.00 ** Cebuana Lhuillier Rural Bank, Inc. P50.00 P15.00 China Bank Savings, Inc.***** FREE FREE China Banking Corporation***** FREE FREE CIMB Bank Philippines, Inc.***** FREE ** Citibank, N.A P100.00 ** Country Builders Bank, Inc.**** FREE ** CTBC Bank (Philippines) Corporation***** FREE P15.00 DCPay Philippines, Inc. P0.00 - P5.00 P0.00- P10.00 Deutsche Bank AG P10.00 - P2,000.00 ** Development Bank of the Philippines***** FREE – *** *** Dungganon Bank, Inc. P10.00 P10.00 East West Banking Corporation*****/**** FREE FREE East West Rural Bank, Inc.*****/**** FREE FREE Equicom Savings Bank, Inc.**** FREE – P15.00 FREE – P15.00 First Consolidated Bank, Inc. -

List of Supervised Financial Institutions with FCDU/EFCDU

BANKS WITH FCDU/EFCDU AUTHORITY as of 31 May 2021 I. UNIVERSAL AND COMMERCIAL BANKS A. EFCDU 1 Al-Amanah Islamic Investment Bank of the Philippines 2 Asia United Bank Corporation 3 Australia and New Zealand Banking Group Limited 4 Bangkok Bank Public Co. Ltd. 5 Bank of America, N.A. 6 Bank of China Limited-Manila Branch 7 Bank of Commerce 8 Bank of the Philippine Islands 9 BDO Unibank, Inc. 10 Cathay United Bank Co., LTD. - Manila Branch 11 Chang Hwa Commercial Bank, Ltd. - Manila Branch 12 China Banking Corporation 13 CIMB Bank Philippines Inc. 14 Citibank, N.A. 15 CTBC Bank (Philippines) Corporation 16 Deutsche Bank AG 17 Development Bank of the Philippines 18 East West Banking Corporation 19 First Commercial Bank, Ltd., Manila Branch 20 Hua Nan Commercial Bank, Ltd. - Manila Branch 21 Industrial and Commercial Bank of China Limited - Manila Branch 22 Industrial Bank of Korea Manila Branch 23 ING Bank N.V. 24 JP Morgan Chase Bank, N.A. 25 KEB Hana Bank - Manila Branch 26 Land Bank of the Philippines 27 Maybank Philippines, Incorporated 28 Mega International Commercial Bank Co., Ltd. 29 Metropolitan Bank and Trust Company 30 Mizuho Bank, Ltd. - Manila Branch 31 MUFG Bank, Ltd. 32 Philippine Bank of Communications 33 Philippine National Bank 34 Philippine Veterans Bank 35 Rizal Commercial Banking Corporation 36 Security Bank Corporation 37 Shinhan Bank - Manila Branch 38 Standard Chartered Bank 39 Sumitomo Mitsui Banking Corporation-Manila Branch 40 The Hongkong & Shanghai Banking Corporation 41 Union Bank of the Philippines 42 United Coconut Planters Bank 43 United Overseas Bank Limited, Manila Branch B. -

General List of Banks of the Philippines

Powers of a universal bank A universal bank has the same powers as a commercial bank with the following additional powers: the powers of an investment house as provided in existing laws and the power to invest in non-allied enterprises. List of local universal banks Government-owned Al-Amanah Islamic Investment Bank of the Philippines Development Bank of the Philippines Land Bank of the Philippines Private-owned 1. Banco de Oro Universal Bank 2. Metropolitan Bank and Trust Company 3. Bank of the Philippine Islands 4. Philippine National Bank 5. Rizal Commercial Banking Corporation 6. UnionBank of the Philippines 7. China Banking Corporation 8. Citibank 9. East West Bank 10. Philippine Savings Bank 11. Philtrust Bank (Philippine Trust Company) 12. Security Bank 13. United Coconut Planters Bank 14. Allied Bank Corporation Powers of a commercial bank In addition to having the powers of a thrift bank, a commercial bank has the power to accept drafts and issue letters of credit; discount and negotiate promissory notes, drafts, bills of exchange, and other evidences of debt; accept or create demand deposits; receive other types of deposits and deposit substitutes; buy and sell foreign exchange and gold or silver bullion; acquire marketable bonds and other debt securities; and extend credit. List of local commercial banks Asia United Bank Bank of Commerce BDO Private Bank (subsidiary of Banco de Oro) Philippine Bank of Communications Philippine Veterans Bank Robinsons Bank Corporation List of foreign banks with commercial banking operations Branches Australia and New Zealand Banking Group Bangkok Bank Bank of America, N.A. Bank of China Chinatrust Commercial Bank Citibank, N.A. -

Application for Credit Card Union Bank

Application For Credit Card Union Bank Lauren unclothes lineally. Which Niall outjuttings so slap that Scot vanishes her wantons? When Martainn urinate his speeds revivings not circumstantially enough, is Saunder irredeemable? Is for credit card application process takes the banking and usability of use. If you sick the features of as regular credit card lacking, you support buy that data special item to top work your usual shopping spending. Do or offer a debit card? Complete the entire rental transaction on your Visa card and receive reimbursement for damage due to collision or theft up to the actual cash value of most rental vehicles. Aside from your credits and merchandise or singapore airlines, then enter a citibank, the computation of credit limit, or two preferred. Take advantage with the option of allocating your credit limit between your principal and supplementary credit cards so you can get to monitor your finances the way you like it. We might Move it You! Receive rank high credit limit its use fetch to buy many extra pill during your shopping sprees. Build credit card application for union bank of standard chartered online id and merchandise rewards points redeemable any unauthorized us help make site. Looking for credit card application for a bank world to enjoy a response. Set half an automatic transfer express will occur as the same background each month. How are you for union? Terms and conditions subject to change. Zero Liability policy does agile apply where certain health card and prepaid card transactions or transactions not processed by Visa. Looking for a New Credit Card? With Electronic Statement you think learn both the latest offers and promotions quicker as he receive your statements via email. -

A Status Report on the Philippine Financial System

A Status Report on the Philippine Financial System Second Semester 2005 Bangko Sentral ng Pilipinas Manila, Philippines This semestral report is prepared pursuant to Section 39(c), Article V of the New Central Bank Act (R.A. No. 7653) by the Office of Supervisory Policy Development, Supervision and Examination Sector, Bangko Sentral ng Pilipinas. A synopsis of the report is on the Web at http://www.bsp.gov.ph. STATUS REPORT ON THE PHILIPPINE FINANCIAL SYSTEM, SECOND SEMESTER 2005 TABLE OF CONTENTS PAGE NO. GLOSSARY OF TERMS……………………………………………… II PROLOGUE………………………………………………………….. V THE PHILIPPINE FINANCIAL SYSTEM: AN ASSESSMENT………… 1 THE PHILIPPINE BANKING SYSTEM…………………......…. 11 UNIVERSAL AND COMMERCIAL BANKS……………… 29 THRIFT BANKS………………………………………… 48 RURAL BANKS…………………………………………. 62 COOPERATIVE BANKS…………………………………. 73 THE NON-BANK FINANCIAL INSTITUTIONS NON-BANK FINANCIAL INSTITUTION WITH QUASI-BANKING FUNCTIONS (NBQBS)………... 82 NON-STOCK SAVINGS AND LOAN ASSOCIATIONS…. 87 THE PHILIPPINE OFFSHORE BANKING SYSTEM…………… 91 TRUST OPERATIONS…………………………………………. 94 TABLES SCHEDULES SCHEDULE 1 FINANCIAL INSTITUTIONS UNDER BSP SUPERVISION/REGULATION SCHEDULE 2 COMPARATIVE STATEMENT OF CONDITION SCHEDULE 3 SELECTED CONTINGENT ACCOUNTS SCHEDULE 4 TRUST AND FUND MANAGEMENT OPERATIONS SCHEDULE 5 COMPARATIVE STATEMENT OF INCOME AND EXPENSES APPENDIX 1 CHANGES IN BANK REGULATIONS (JANUARY TO DECEMBER 2005) APPENDIX 2 DIRECTORY OF PHILIPPINE BANKS’/NBQBS’/OFFSHORE BANKS’ HEAD OFFICES Source: Office of Supervisory Policy Development, Supervision and Examination Sector STATUS REPORT ON THE PHILIPPINE FINANCIAL SYSTEM, SECOND SEMESTER 2005 GLOSSARY A. SELECTED ACCOUNTS 1. Total assets refer to the sum of all assets, adjusted to net off the accounts “Due from Head Office/Branches/Agencies” and “Due to Head Office/Branches/Agencies” of foreign bank branches.