2005, Our Research Has Led Us to Five Main Conclusions About the Nature of the Media Landscape

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Practice of Advertising to Jan, Always the Practice of Advertising

The Practice of Advertising To Jan, always The Practice of Advertising Edited by Adrian R. Mackay Fifth edition AMSTERDAM ● BOSTON ● HEIDELBERG ● LONDON ● NEW YORK ● OXFORD PARIS ● SAN DIEGO ● SAN FRANCISCO ● SINGAPORE ● SYDNEY ● TOKYO Elsevier Butterworth-Heinemann Linacre House, Jordan Hill, Oxford OX2 8DP 30 Corporate Drive, Burlington, MA 01803 First published 1978 Reprinted 1981 Second edition 1983 Reprinted 1984, 1985, 1986 Third edition 1990 Reprinted 1990, 1993 Fourth edition 1995 Reprinted 1996, 2001 Fifth edition 2005 Copyright © 2005, Elsevier Ltd. All rights reserved No part of this publication may be reproduced in any material form (including photocopying or storing in any medium by electronic means and whether or not transiently or incidentally to some other use of this publication) without the written permission of the copyright holder except in accordance with the provisions of the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988 or under the terms of a licence issued by the Copyright Licensing Agency Ltd, 90 Tottenham Court Road, London, England W1T 4LP. Applications for the copyright holder’s written permission to reproduce any part of this publication should be addressed to the publisher Permissions may be sought directly from Elsevier’s Science & Technology Rights Department in Oxford, UK: phone: (ϩ144) 1865 843830, fax: (ϩ144) 1865 853333, e-mail: [email protected]. You may also complete your request on-line via the Elsevier homepage (http://www.elsevier.com), by selecting ‘Customer Support’ and then ‘Obtaining Permissions’ -

Shafiq Rahman

Curriculum Vitae Shafiq Rahman Professor and Chair Communication & Social Sciences Department Chadron State College 1000 Main Street, Chadron NE 69337 Tel: 308-432-6327 (work) [email protected] EDUCATION Ph.D. Mass Communication and Media Arts, December 2007 (Southern Illinois University, Carbondale). M.A. Communication, December 2001 (The University of Louisiana, Monroe). M.A. Mass Communication and Journalism, June 1992 (Dhaka University, Bangladesh). B.A. (Honors), Mass Communication and Journalism, June 1989 (Dhaka University, Bangladesh). EMPLOYMENT: UNITED STATES Professor (since August 16, 2015) and Chair, Department of Communication and Social Sciences at Chadron State College, August 2016—till date. Associate Professor, Communication and Social Sciences Department, Chadron State College, August 16, 2010—August 15, 2015. Assistant Professor, Communication and Social Sciences Department, Chadron State College, August 16, 2007—August 15, 2010. Instructor in record, School of Journalism, Southern Illinois University Carbondale, spring 2007(January— May). Teaching Assistant- School of Journalism, Southern Illinois University Carbondale (August 2003— December 2006). Research Assistant (quarter time), Aug. 2001- May 2001, and Aug. 2003-December 2006, School of Journalism, Southern Illinois University Carbondale. Research Assistant, Dept. of Mass Communications, The University of Louisiana Monroe, Aug 1999-May 2001. Shift Supervisor, Information Technology Computer Learning Center, Southern Illinois University Carbondale, Aug 2001—May 2003. TEACHING I developed and taught a wide variety of classes in face-to-face and online formats. A significant part of teaching involves the instruction of graduate and undergraduate research methods and intercultural communication. I have also developed and taught media writing, media survey (introduction to media), communication theory, public speaking, persuasion, organization communication, and social media. -

Periodicalspov.Pdf

“Consider the Source” A Resource Guide to Liberal, Conservative and Nonpartisan Periodicals 30 East Lake Street ∙ Chicago, IL 60601 HWC Library – Room 501 312.553.5760 ver heard the saying “consider the source” in response to something that was questioned? Well, the same advice applies to what you read – consider the source. When conducting research, bear in mind that periodicals (journals, magazines, newspapers) may have varying points-of-view, biases, and/or E political leanings. Here are some questions to ask when considering using a periodical source: Is there a bias in the publication or is it non-partisan? Who is the sponsor (publisher or benefactor) of the publication? What is the agenda of the sponsor – to simply share information or to influence social or political change? Some publications have specific political perspectives and outright state what they are, as in Dissent Magazine (self-described as “a magazine of the left”) or National Review’s boost of, “we give you the right view and back it up.” Still, there are other publications that do not clearly state their political leanings; but over time have been deemed as left- or right-leaning based on such factors as the points- of-view of their opinion columnists, the make-up of their editorial staff, and/or their endorsements of politicians. Many newspapers fall into this rather opaque category. A good rule of thumb to use in determining whether a publication is liberal or conservative has been provided by Media Research Center’s L. Brent Bozell III: “if the paper never met a conservative cause it didn’t like, it’s conservative, and if it never met a liberal cause it didn’t like, it’s liberal.” Outlined in the following pages is an annotated listing of publications that have been categorized as conservative, liberal, non-partisan and religious. -

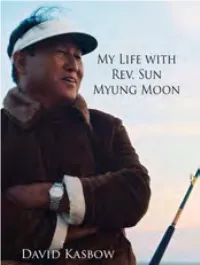

David Kasbow Acknowledgments M

My Life with Rev. Sun Myung Moon My Life with Rev. Sun Myung Moon M David Kasbow Acknowledgments M want to acknowledge the many friends who helped with advice on the I writing and design of this book. Especially, I want to thank Koji Foreman, a nineteen year old young man, wise beyond his years, who asked to read my original draft. To my surprise he sent me many pages of comments and reflec- tions that helped me begin forming a stack of stories into this book as it is today. I am grateful to the members of my church and my family for their patience as I took time away from them to accomplish this account of my life. Finally, I wish that I could personally acknowledge each person, famous or unknown, who throughout history sought God, especially those who were drawn to God when God was doing something new, when the road was not clear, not in line with traditional customs. I give thanks to all of them for creat- ing the incredible spiritual foundation we stand on today. 5 Contents Acknowledgments . .5 Preface . .9 Rev . Moon’s Ministry and Mission . 11 The Mission Unfolds . .14 Gaining Followers . .17 My Early Life . 19 Joining the Church . 24 The Tours . 28 President Nixon . .34 The 32 City Tour . 38 Madison Square Garden . .40 Global Team . .44 Korea . .47 Prayers for Ancestors . 53 Bismarck . .57 Yankee Stadium and Washington Monument . .62 Vermont . 67 6 Mobile Fundraising Teams . .72 Marriage . .79 The Washington Times ................................... 88 Tuna . .95 Unification Theological Seminary . .99 Going Home to Detroit . -

Journal, Summer 2009 | National Association of Black Journalists

Journal, Summer 2009 | www.nabj.org | National Association of Black Journalists | 1 2 | National Association of Black Journalists | www.nabj.org | Journal, Summer 2009 Table of Contents Features 6 – Prime Movers. Program started by former NABJ President grooms future journalists 8 – The Contenders. Angelo Henderson and Kathy Times are both able, willing and passionate about being the next NABJ President. See how the candidates, as well as the candidates for the 2009-2011 Board of Directors, stack up. Cover Story – NABJ Special Honors 12 – Journalist of the Year – National Public Radio’s Michele Norris 16 – Lifetime Achievement – Michael Wilbon 18 – Legacy Award – Sandra Rosenbush and Leon Carter 20 – Student Journalist of the Year – Jamisha Purdy 22 – Educator of the Year – Lawrence Kaggwa 24 – Hall of Famers – Caldwell, Norment, Peterman and Whiteside inducted 26 – Emerging Journalist of the Year – Cynthia Gordy, Essence Magazine 27 – Community Service Award – The Chauncey Bailey Project 27 – Percy Qoboza Foreign Journalist Award – Andrison Shadreck Manyere NABJ Convention 30 – Welcome to Tampa. Departments President’s Column .............................................................4 8 – Election 2009: Kathy Times, the current NABJ Executive Director .............................................................5 VP of Broadcast, and Angelo Henderson, a former Comings and Goings .......................................................34 parliamentarian, are both now seeking the organization’s Passages .........................................................................35 presidency. Read more on page 8. Photos by Ad Seymour. Cover Photo by Mark Gail / Washington Post The NABJ Journal (USPS number pending) is published quarterly by the National Association of Black Journalists (NABJ) at 8701-A Adelphi Road, Adelphi, MD 20783-1716. Pending periodicals postage is paid at Adelphi, MD. NABJ is the largest organization of journalists of color in the nation. -

Marilyn Monroe, Lived in the Rear Unit at 5258 Hermitage Avenue from April 1944 to the Summer of 1945

Los Angeles Department of City Planning RECOMMENDATION REPORT CULTURAL HERITAGE COMMISSION CASE NO.: CHC-2015-2179-HCM ENV-2015-2180-CE HEARING DATE: June 18, 2015 Location: 5258 N. Hermitage Avenue TIME: 10:30 AM Council District: 2 PLACE: City Hall, Room 1010 Community Plan Area: North Hollywood – Valley Village 200 N. Spring Street Area Planning Commission: South Valley Los Angeles, CA Neighborhood Council: Valley Village 90012 Legal Description: TR 9237, Block None, Lot 39 PROJECT: Historic-Cultural Monument Application for the DOUGHERTY HOUSE REQUEST: Declare the property a Historic-Cultural Monument OWNER(S): Hermitage Enterprises LLC c/o Joe Salem 20555 Superior Street Chatsworth, CA 91311 APPLICANT: Friends of Norma Jean 12234 Chandler Blvd. #7 Valley Village, CA 91607 Charles J. Fisher 140 S. Avenue 57 Highland Park, CA 90042 RECOMMENDATION That the Cultural Heritage Commission: 1. NOT take the property under consideration as a Historic-Cultural Monument per Los Angeles Administrative Code Chapter 9, Division 22, Article 1, Section 22.171.10 because the application and accompanying photo documentation do not suggest the submittal warrants further investigation. 2. Adopt the report findings. MICHAEL J. LOGRANDE Director of Planning [SIGN1907 [SIGNED ORIGINAL IN FILE] [SIGNED ORIGINAL IN FILE] Ken Bernstein, AICP, Manager Lambert M. Giessinger, Preservation Architect Office of Historic Resources Office of Historic Resources [SIGNED ORIGINAL IN FILE] Shannon Ryan, City Planning Associate Office of Historic Resources Attachments: Historic-Cultural Monument Application CHC-2015-2179-HCM 5258 N. Hermitage, Dougherty House Page 2 of 3 SUMMARY The corner property at 5258 Hermitage is comprised of two one-story buildings. -

Scoville, Curtailing the Cudgel of "Coordination"

Curtailing the Cudgel of “Coordination” by Curing Confusion: How States Can Fix What the Feds Got Wrong on Campaign Finance GEORGE S. SCOVILLE III* I. INTRODUCTION.......................................................................... 465 II. FEDERAL COORDINATION DOCTRINE ........................................ 475 A. Establishing the Regime .............................................. 475 1. The Federal Election Campaign Act and Buckley’s Curious Dual Anti-Corruption Rationale ................ 475 2. The Bipartisan Campaign Reform Act, the FEC’s Coordination Regulations, and Recent Cases .......... 482 B. Hypos Showing Ambiguity in Federal Conduct Standards ...................................................... 487 1. The Coffee Shop Hypo........................................... 487 2. The Photo Hypo ..................................................... 488 3. The Polling Hypo ................................................... 489 * Editor-in-Chief, Volume 48 The University of Memphis Law Review; Candidate for Juris Doctor and Business Law Certificate, 2018, The University of Memphis Cecil C. Humphreys School of Law; Master of Public Policy, 2011, American University School of Public Affairs. For Emily, whose steadfast love has been the sine qua non of my studies. Thank you to countless family, friends, colleagues, and mentors for boundless guidance and support, especially Capital University Josiah H. Blackmore II/Shirley M. Nault Professor of Law Bradley A. Smith, Cecil C. Humphreys School of Law Professors Steven J. Mulroy and John M. Newman, and my colleagues, past and present, at The University of Memphis Law Review, especially Callie Tran, Liz Stagich, and Connor Dugosh. “If I have seen further, it is by standing on ye shoulders of giants.” Letter from Isaac Newton to Robert Hooke (Feb. 5, 1675) (on file with the Historical Society of Pennsylvania), http://digitallibrary.hsp.org/index.php/Detail/Object/Show/object_id/9285. 463 464 The University of Memphis Law Review Vol. -

Gray Lady Down:Encounter TEXT-Excerpt: CHAP 3

Gray Lady Down What the Decline and Fall of the New York Times Means for America WILLIAM MCGOWAN Chapter Three: Bullets over Arthur Jr. Abe Rosenthal’s funeral in 2006 became an occasion for nostalgia over the death of the Times’ golden days, a recessional for the paper’s transition from the voice of America to an increasingly self-righteous, and politically correct, left-liberal publication. It also became a moment for pause when the effects of young Arthur’s fifteen-year reign could be evaluated. It was not a pretty picture. In a relatively few years, a paper that had been known as the gold standard of American journalism had been tarnished by a string of embarrassing incidents, casting it in the harshest of spotlights, putting its credibility and even its patriotism on the line. Its newsroom had been accused of hypocrisy, corruption, ineptitude, ethical misconduct, fraud, plagiarism, credulousness and, most seriously, ideological bias. The business side was equally under siege, and its board—stacked with Sulzbergers—had presided over a plummeting of stock value to half what it had been in 2002, with advertising revenues in free fall. This steady parade of embarrassing lowlights, where the Times had become the focus of the news instead of merely the bearer of it, had revealed cracks in its foundations and made it a target for public anger and derision—as well as a possible candidate for a corporate takeover. Every time one of these incidents occurred, the Times and its partisan defenders—led by Arthur Jr. himself—had tried to depict it as an isolated case, refusing to acknowledge any pattern. -

March 2013 Sunday Morning Talk Show Data

March 2013 Sunday Morning Talk Show Data March 3, 2013 25 men and 10 women NBC's Meet the Press with David Gregory: 5 men and 2 women Speaker of the House John Boehner (M) Gene Sperling (M) Rep. Raul Labrador (M) Kathleen Parker (F) Joy Reid (F) Chuck Todd (M) Tom Brokaw (M) CBS's Face the Nation with Bob Schieffer: 7 men and 1 woman Sen. Lindsey Graham (M) Sen. John McCain (M) Sen. Majority Whip Dick Durbin (M) Cardinal Timothy Dolan (M) Bob Woodward (M) David Sanger (M) Rana Foroohar (F) John Dickerson (M) ABC's This Week with George Stephanopoulos: 4 men and 3 women Gene Sperling (M) Sen. Kelly Ayotte (F) James Carville (M) Matthew Dowd (M) Paul Gigot (M) Mayor Mia Love (F) Cokie Roberts (F) CNN's State of the Union with Candy Crowley: 6 men and 1 woman Sen. Minority Leader Mitch McConnell (M) Gene Sperling (M) Rep. Steve Israel (M) Rep. Greg Walden (M) Mark Zandi (M) Stephen Moore (M) Susan Page (F) Fox News' Fox News Sunday with Chris Wallace: 3 men and 3 women Fmr. Gov. Mitt Romney (M) Ann Romney (F) Bill Kristol (M) Kirsten Powers (F) Fmr. Sen. Scott Brown (F) Charles Lane (M) March 10, 2013 25 men and 13 women NBC's Meet the Press with David Gregory: 6 men and 3 women Sen. Tim Kaine (M) Sen. Tom Coburn (M) Rep. Tulsi Gabbard (F) Rep. Cory Garnder (M) Joe Scarborough (M) Dee Dee Myers (F) Rep. Marsha Blackburn (F) Steve Schmidt (M) Ruth Marcus (F) Fmr. -

21 Types of News

21 Types Of News In the fIrst several chapters, we saw media systems in flux. Fewer newspaper journalists but more websites, more hours of local TV news but fewer reporters, more “news/talk” radio but less local news radio, national cable news thriving, local cable news stalled. But what matters most is not the health of a particular sector but how these changes net out, and how the pieces fit together. Here we will consider the health of the news media based on the region of coverage, whether neigh- borhood, city, state, country, or world. Hyperlocal The term “hyperlocal” commonly refers to news coverage on a neighborhood or even block-by-block level. The tradi- tional media models, even in their fattest, happiest days could not field enough reporters to cover every neighborhood on a granular level. As in all areas, there are elements of progress and retreat. On one hand, metropolitan newspapers have cut back on regional editions, which in all likelihood means less coverage of neighborhoods in those regions. But the Internet has revolutionized the provision of hyperlocal information. The first wave of technology— LISTSERV® and other email groups—made it far easier for citizens to inform one another of what was happening with the neighborhood crime watch or the new grocery store or the death of citizens can now snap a beloved senior who lived on the block for 40 years. More recently, social media tools have enabled citizens to self-organize, and connect in ever more picture of potholes and dynamic ways. Citizens can now snap pictures of potholes and send them to send to city hall, or share city hall, or share with each other via Facebook, Twitter or email. -

The Time of Our Lives: a Conversation with Peggy Noonan and John Dickerson

AMERICAN ENTERPRISE INSTITUTE THE TIME OF OUR LIVES: A CONVERSATION WITH PEGGY NOONAN AND JOHN DICKERSON INTRODUCTION: ARTHUR C. BROOKS, AEI CONVERSATION: JOHN DICKERSON, CBS NEWS PEGGY NOONAN, THE WALL STREET JOURNAL 5:30 PM – 6:30 PM WEDNESDAY, NOVEMBER 18, 2015 EVENT PAGE: https://www.aei.org/events/the-time-of-our-lives-a-conversation- with-peggy-noonan-and-john-dickerson/ TRANSCRIPT PROVIDED BY DC TRANSCRIPTION – WWW.DCTMR.COM ARTHUR BROOKS: (In progress) – speeches of the great Reagan administration. Peggy’s a CBS News contributor and the author of several books, a lot of bestsellers. This new book, which I recommend to you for your interest, is some of her finest and most memorable columns, most powerful columns from the last few years, “The Time of Our Lives.” Joining Peggy for this discussion is John Dickerson. John is the political director for CBS News and the new anchor – newish anchor of “Face the Nation.” That show is getting more and more notoriety because of the excellence of John. I’m sure you’re watching it, and you should. Just last weekend, he moderated the Democratic debate. Popular press says that he was the winner of that debate. (Applause.) We’re looking forward to the conversation. Whether you’re new to AEI or an old friend, please come back. These conversations are a part of what we do and we couldn’t do them without you. So, with that, please join me in welcoming Peggy Noonan and John Dickerson. (Applause.) PEGGY NOONAN: Thank you. Thank you. JOHN DICKERSON: Thank you. -

Crime, Class, and Labour in David Simon's Baltimore

"From here to the rest of the world": Crime, class, and labour in David Simon's Baltimore. Sheamus Sweeney B.A. (Hons), M.A. (Hons) This thesis is submitted to Dublin City University for the award of Ph.D in the Faculty of Humanities and Social Sciences. August 2013 School of Communications Supervisors: Prof. Helena Sheehan and Dr. Pat Brereton I hereby certify that this material, which I now submit for assessment on the programme of study leading to the award of Ph.D is entirely my own work, and that I have exercised reasonable care to ensure that the work is original, and does not to the best of my knowledge breach any law of copyright, and has not been taken from the work of others save and to the extent that such work has been cited and acknowledged within the text of my work. Signed: ___________________________________ (Candidate) ID No.: _55139426____ Date: _______________ TABLE OF CONTENTS Introduction 1 Literature review and methodology 17 Chapter One: Stand around and watch: David Simon and the 42 "cop shop" narrative. Chapter Two: "Let the roughness show": From death on the 64 streets to a half-life on screen. Chapter Three: "Don't give the viewer the satisfaction": 86 Investigating the social order in Homicide. Chapter Four: Wasteland of the free: Images of labour in the 122 alternative economy. Chapter Five: The Wire: Introducing the other America. 157 Chapter Six: Baltimore Utopia? The limits of reform in the 186 war on labour and the war on drugs. Chapter Seven: There is no alternative: Unencumbered capitalism 216 and the war on drugs.