The Time of Our Lives: a Conversation with Peggy Noonan and John Dickerson

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Analysis of Talk Shows Between Obama and Trump Administrations by Jack Norcross — 69

Analysis of Talk Shows Between Obama and Trump Administrations by Jack Norcross — 69 An Analysis of the Political Affiliations and Professions of Sunday Talk Show Guests Between the Obama and Trump Administrations Jack Norcross Journalism Elon University Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements in an undergraduate senior capstone course in communications Abstract The Sunday morning talk shows have long been a platform for high-quality journalism and analysis of the week’s top political headlines. This research will compare guests between the first two years of Barack Obama’s presidency and the first two years of Donald Trump’s presidency. A quantitative content analysis of television transcripts was used to identify changes in both the political affiliations and profession of the guests who appeared on NBC’s “Meet the Press,” CBS’s “Face the Nation,” ABC’s “This Week” and “Fox News Sunday” between the two administrations. Findings indicated that the dominant political viewpoint of guests differed by show during the Obama administration, while all shows hosted more Republicans than Democrats during the Trump administration. Furthermore, U.S. Senators and TV/Radio journalists were cumulatively the most frequent guests on the programs. I. Introduction Sunday morning political talk shows have been around since 1947, when NBC’s “Meet the Press” brought on politicians and newsmakers to be questioned by members of the press. The show’s format would evolve over the next 70 years, and give rise to fellow Sunday morning competitors including ABC’s “This Week,” CBS’s “Face the Nation” and “Fox News Sunday.” Since the mid-twentieth century, the overall media landscape significantly changed with the rise of cable news, social media and the consumption of online content. -

WHCA): Videotapes of Public Affairs, News, and Other Television Broadcasts, 1973-77

Gerald R. Ford Presidential Library White House Communications Agency (WHCA): Videotapes of Public Affairs, News, and Other Television Broadcasts, 1973-77 WHCA selectively created, or acquired, videorecordings of news and public affairs broadcasts from the national networks CBS, NBC, and ABC; the public broadcast station WETA in Washington, DC; and various local station affiliates. Program examples include: news special reports, national presidential addresses and press conferences, local presidential events, guest interviews of administration officials, appearances of Ford family members, and the 1976 Republican Convention and Ford-Carter debates. In addition, WHCA created weekly compilation tapes of selected stories from network evening news programs. Click here for more details about the contents of the "Weekly News Summary" tapes All WHCA videorecordings are listed in the table below according to approximate original broadcast date. The last entries, however, are for compilation tapes of selected television appearances by Mrs. Ford, 1974-76. The tables are based on WHCA’s daily logs. “Tape Length” refers to the total recording time available, not actual broadcast duration. Copyright Notice: Although presidential addresses and very comparable public events are in the public domain, the broadcaster holds the rights to all of its own original content. This would include, for example, reporter commentaries and any supplemental information or images. Researchers may acquire copies of the videorecordings, but use of the copyrighted portions is restricted to private study and “fair use” in scholarship and research under copyright law (Title 17 U.S. Code). Use the search capabilities of your PDF reader to locate specific names or keywords in the table below. -

CBS NEWS 2020 M Street N.W

CBS NEWS 2020 M Street N.W. Washington, D.C. 20036 FACE THE NATION as broadcast over the CBS Television ~et*k and the -.. CBS Radio Network Sunday, August 6, 1967 -- 12:30-1:00 PM EDT NEWS CORREIS PONDENTS : Martin Agronsky CBS News Peter Lisagor Chicago Daily News John Bart CBS News DIRECTOR: Robert Vitarelli PRODUCEBS : Prentiss Childs and Sylvia Westerman CBS NEWS 2020 M Street, N.W. Washington, D.C. 20036 FOR IMMEDIATE RELEFSE HIGHLIGHTS FROM REMARKS OF HONORABLE EVERETT DIREEN, ,- U.S. SENATOR, REPUBLICAN OF ILLINOIS, ON "FACE THE NATI(3N" ON THE CBS TELEVISION AND THE CBS RADIO NETWORKS, SUNDAY, AUGUST 6, 1967 - 12:30-1:00 PM EST: -PAGE Riots and Urban problems Presented Republican Party statement blaming Pres. Johnson for riots, but would personally be cautious about allegations 1 and 13 In a good many communities there is evidence of outside in£luences triggering riots If conditions not ameliorated--will be "one of the monumental in '68" 3 issues -- - . -- - Congress has -not been "niggardly"--will kead figures to _Mayor Jerome Cavanagh before the Committee 8 Cincinnati police chief told Committee city was in good shape 9 Stokley Carmichael--treason is a sinister charge--must be proven 17 Vietnam Supports President ' s policy--he has most expert advice 4 and 5 7 Gun control bill Can better be handled at state level Would go along with moderate bill 4R. AGRONSKX: Senator Dirksen, a recent Republican Party ;tatement read by you blamed President Johnson for the racial riots. Your Republican colleague, Senator Thrus ton rIorton, denounced this as irresponsible. -

Saint Jude the Apostle Church Ask Seek Knock

Ask July 28, 2019 and will receive, Seventeenth Sunday in Ordinary Time Seek PASTORAL STAFF and you will find; CLERGY Rev. John J. Detisch Pastor [email protected] Knock Rev. T. Shane Mathew Weekend Assistant and the door will be Deacon Richard Brogdon Deacon Assistant [email protected] opened to you. PARISH LAY STAFF MASS & CONFESSION TIMES Matt Costa Pastoral Minister [email protected] Weekend Masses: Jennifer Hudson Administrative Assist. Saturday evening: 4:30 p.m. [email protected] Sunday: 7:30, 9:00, and 10:30 a.m. Catherine Evans Director of Finance Weekday Masses: [email protected] Tuesday: 6:30 p.m. Jesse Spanogle Director of Faith Wednesday: 8:00 a.m. Formation Thursday: 8:00a.m. [email protected] Friday: 8:00 a.m. Chris McAdams Director of Facilities Holy Day Masses Holy Day: Please refer to the bulletin for Bruce & Trisha Yates Music Ministry mass times [email protected] Reconciliation: Katrina Foltz Accompanist Saturday: 3:30-4:00 p.m. We welcome all new parish families and visitors to Saint Jude the Apostle Church. Please reach out to our Parish Office at (814) 833-0927 to register or go online at www.stjudeapos.org. As a parish member of Saint Jude’s, you are actively supporting our parish mission of time, talents, and treasures. Welcome to Saint Jude the Apostle Church! Saint Jude the Apostle Church A Welcoming Family of Faith 2801 West 6th Street Erie, Pennsylvania 16505 Phone: 814-833-0927 Fax: 814-833-9692 Web Page www.stjudeapos.org Seventeenth Sunday in Ordinary Time July 28, 2019 From the desk of the Pastor At last weekend’s Masses in which I presided, I preached about a fantastic article that we written by Peggy Noonan of the Wall Street Journal. -

Face the Nation: CBS (Nixon), October 27, 1968

I CBS NBPS 2020 M Stree t, N. W. Hasbinglo·: , D. C. 2003G as broadcast over the CBS Tc levis i. on Network and tlle CBS Radio Ne b·i'Or k Sunday, October 27 , 1968·- 6:30-7:00 P!'·J. EST GUES T:. RIGIARD M. NIXON Republican Candidate fo.1~ President NE\•;6 CORR"ES PONDENTS: Martin Agronsky CBS Ne'i·iS David Broder 'l'he v7ashington Post ,John Hart CBS News DIREC'J.'OTI: Robert Vi ta:re lli PRODUCE RS: Sylvia v7esterman an::'l Prentiss Childs ·.: NOTF: TO EDri'ORS: PJ_ease c recl:it any rruote s or excerpts from this CBS R::Jd:io and T~·d evis ion pro9ram to "Face t he Nation." P RESS CONTACT: Ethel Aaronson - ( 202) 29G-1234 , 1 .0 you .0 1 HR. AGROF:SKY: l"i:C. Nixon, President Johnson today accused ( '1 co N ,......0 2 of making ugly and unfair distortions of An:3r i can defense po.,. N 0 N 0 0 own pcace-rnak.ing efforts. Do you feel that, 3. 3 sitions and of his 0 c 0 .S!a. 4 despite your own moratorium against i t , tl1e peace negoti ations 5 };ave now been brought i nto the polj tical c ampaign? 6 MR. KIXON: I c ertainly do not , b ecause I made it very cle2r 7 that anything I said about the VLetnam negotiations , t hat I 8 would not discuss wh at the negotiators should agree to. I 9 believe that President Johnson should have absolute freedo:11 o f 10 action to negotiate what he finds i s t l!e proper ~~ ind o f settle- 11 ment. -

Lesley Stahl - 60 Minutes - CBS News

Lesley Stahl - 60 Minutes - CBS News http://www.cbsnews.com/stories/1998/07/09/60minutes/main13546.shtml C Lesley Stahl Correspondent, 60 Minutes (CBS) Lesley Stahl has been a 60 Minutes correspondent since March 1991. The 2008-09 season marks her 18th on the broadcast. Stahl’s interviews with the families of the Duke Lacrosse players exonerated in a racial rape case and with Nancy Pelosi before she became the first woman to become speaker of the house were big scoops for 60 Minutes and 60 Minutes and CBS News Correspondent CBS News in 2007. In September of 2005, Stahl landed the Lesley Stahl (CBS) first interview with American hostage Roy Hallums who was held captive by Iraqis for 10 months. Her other exclusive 60 Minutes interviews with former Bush administration officials Paul O’Neill and Richard Clarke ranked among the biggest news stories of 2004. She was the first to report that Al Gore would not run for president, in a 60 Minutes interview broadcast in 2002. Prior to joining 60 Minutes, Stahl served as CBS News White House correspondent during the Carter and Reagan presidencies and part of the term of George H. W. Bush. Her reports appeared frequently on the CBS Evening News, first with Walter Cronkite, then with Dan Rather, and on other CBS News broadcasts. During much of that time, she also served as moderator of Face The Nation, CBS News' Sunday public-affairs broadcast (September 1983-May 1991). For Face The Nation, she interviewed such newsmakers as Margaret Thatcher, Boris Yeltsin, Yasir Arafat and virtually every top U.S. -

The Bush Revolution: the Remaking of America's Foreign Policy

The Bush Revolution: The Remaking of America’s Foreign Policy Ivo H. Daalder and James M. Lindsay The Brookings Institution April 2003 George W. Bush campaigned for the presidency on the promise of a “humble” foreign policy that would avoid his predecessor’s mistake in “overcommitting our military around the world.”1 During his first seven months as president he focused his attention primarily on domestic affairs. That all changed over the succeeding twenty months. The United States waged wars in Afghanistan and Iraq. U.S. troops went to Georgia, the Philippines, and Yemen to help those governments defeat terrorist groups operating on their soil. Rather than cheering American humility, people and governments around the world denounced American arrogance. Critics complained that the motto of the United States had become oderint dum metuant—Let them hate as long as they fear. September 11 explains why foreign policy became the consuming passion of Bush’s presidency. Once commercial jetliners plowed into the World Trade Center and the Pentagon, it is unimaginable that foreign policy wouldn’t have become the overriding priority of any American president. Still, the terrorist attacks by themselves don’t explain why Bush chose to respond as he did. Few Americans and even fewer foreigners thought in the fall of 2001 that attacks organized by Islamic extremists seeking to restore the caliphate would culminate in a war to overthrow the secular tyrant Saddam Hussein in Iraq. Yet the path from the smoking ruins in New York City and Northern Virginia to the battle of Baghdad was not the case of a White House cynically manipulating a historic catastrophe to carry out a pre-planned agenda. -

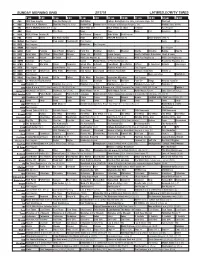

Sunday Morning Grid 2/17/19 Latimes.Com/Tv Times

SUNDAY MORNING GRID 2/17/19 LATIMES.COM/TV TIMES 7 am 7:30 8 am 8:30 9 am 9:30 10 am 10:30 11 am 11:30 12 pm 12:30 2 CBS CBS News Sunday Face the Nation (N) Bull Riding College Basketball Ohio State at Michigan State. (N) PGA Golf 4 NBC Today in L.A. Weekend Meet the Press (N) (TVG) Hockey Day Hockey New York Rangers at Pittsburgh Penguins. (N) Hockey: Blues at Wild 5 CW KTLA 5 Morning News at 7 (N) Å KTLA News at 9 KTLA 5 News at 10am In Touch Paid Program 7 ABC News This Week News News News Paid American Paid 9 KCAL KCAL 9 News Sunday (N) Joel Osteen Jentzen Mike Webb Paid Program 1 1 FOX Planet Weird Fox News Sunday News PBC Face NASCAR RaceDay (N) 2019 Daytona 500 (N) 1 3 MyNet Paid Program Fred Jordan Freethought Paid Program News Paid 1 8 KSCI Paid Program Buddhism Paid Program 2 2 KWHY Paid Program Paid Program 2 4 KVCR Paint Painting Joy of Paint Wyland’s Paint This Painting Kitchen Mexican Martha Christina Baking How To 2 8 KCET Zula Patrol Zula Patrol Mixed Nutz Edisons Curios -ity Biz Kid$ Grand Canyon Huell’s California Adventures: Huell & Louie 3 0 ION Jeremiah Youseff In Touch Paid NCIS: Los Angeles Å NCIS: Los Angeles Å NCIS: Los Angeles Å NCIS: Los Angeles Å 3 4 KMEX Conexión Paid Program Fútbol Fútbol Mexicano Primera División (N) República Deportiva (N) 4 0 KTBN Jeffress Win Walk Prince Carpenter Intend Min. -

Political Journalists Tweet About the Final 2016 Presidential Debate Hannah Hopper East Tennessee State University

East Tennessee State University Digital Commons @ East Tennessee State University Electronic Theses and Dissertations Student Works 5-2018 Political Journalists Tweet About the Final 2016 Presidential Debate Hannah Hopper East Tennessee State University Follow this and additional works at: https://dc.etsu.edu/etd Part of the American Politics Commons, Communication Technology and New Media Commons, Gender, Race, Sexuality, and Ethnicity in Communication Commons, Journalism Studies Commons, Political Theory Commons, Social Influence and Political Communication Commons, and the Social Media Commons Recommended Citation Hopper, Hannah, "Political Journalists Tweet About the Final 2016 Presidential Debate" (2018). Electronic Theses and Dissertations. Paper 3402. https://dc.etsu.edu/etd/3402 This Thesis - Open Access is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Works at Digital Commons @ East Tennessee State University. It has been accepted for inclusion in Electronic Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ East Tennessee State University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Political Journalists Tweet About the Final 2016 Presidential Debate _____________________ A thesis presented to the faculty of the Department of Media and Communication East Tennessee State University In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree Master of Arts in Brand and Media Strategy _____________________ by Hannah Hopper May 2018 _____________________ Dr. Susan E. Waters, Chair Dr. Melanie Richards Dr. Phyllis Thompson Keywords: Political Journalist, Twitter, Agenda Setting, Framing, Gatekeeping, Feminist Political Theory, Political Polarization, Presidential Debate, Hillary Clinton, Donald Trump ABSTRACT Political Journalists Tweet About the Final 2016 Presidential Debate by Hannah Hopper Past research shows that journalists are gatekeepers to information the public seeks. -

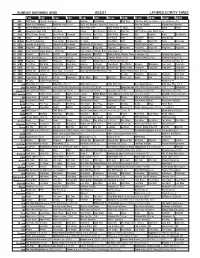

Sunday Morning Grid 8/22/21 Latimes.Com/Tv Times

SUNDAY MORNING GRID 8/22/21 LATIMES.COM/TV TIMES 7 am 7:30 8 am 8:30 9 am 9:30 10 am 10:30 11 am 11:30 12 pm 12:30 2 CBS CBS News Face the Nation (N) News Graham Bull Riding PGA Tour PGA Tour Golf The Northern Trust, Final Round. (N) 4 NBC Today in LA Weekend Meet the Press (N) Å 2021 AIG Women’s Open Final Round. (N) Race and Sports Mecum Auto Auctions 5 CW KTLA 5 Morning News at 7 (N) Å KTLA News at 9 KTLA 5 News at 10am In Touch David Smile 7 ABC Eyewitness News 7AM This Week Ocean Sea Rescue Hearts of Free Ent. 2021 Little League World Series 9 KCAL KCAL 9 News Sunday Joel Osteen Jeremiah Joel Osteen Paid Prog. Mike Webb Harvest AAA Danette Icons The World’s 1 1 FOX Mercy Jack Hibbs Fox News Sunday The Issue News Sex Abuse PiYo Accident? Home Drag Racing 1 3 MyNet Bel Air Presbyterian Fred Jordan Freethought In Touch Jack Hibbs AAA NeuroQ Grow Hair News The Issue 1 8 KSCI Fashion for Real Life MacKenzie-Childs Home MacKenzie-Childs Home Quantum Vacuum Å COVID Delta Safety: Isomers Skincare Å 2 2 KWHY Programa Resultados Revitaliza Programa Programa Programa Programa Programa Programa Programa Programa Programa 2 4 KVCR Great Scenic Railway Journeys: 150 Years Suze Orman’s Ultimate Retirement Guide (TVG) Great Performances (TVG) Å 2 8 KCET Darwin’s Cat in the SciGirls Odd Squad Cyberchase Biz Kid$ Build a Better Memory Through Science (TVG) Country Pop Legends 3 0 ION NCIS: New Orleans Å NCIS: New Orleans Å Criminal Minds (TV14) Criminal Minds (TV14) Criminal Minds (TV14) Criminal Minds (TV14) 3 4 KMEX Programa MagBlue Programa Programa Fútbol Fútbol Mexicano Primera División (N) República deportiva (N) 4 0 KTBN R. -

Washington in the Information Age: ǂb an Insider's Guide to Media

Washington in the Information Age An Insider’s Guide to Media Consumption and Collaboration Inside the Beltway © 2009 National Journal Group A Note on Use of These Materials This document has been prepared by and comprises valuable proprietary information belonging to National Journal Group. It is intended for educational purposes only. Except as permitted under the United States Copyright Act of 1976, no part of this publication may be reproduced or distributed in any form or by any means, or stored in a database retrieval system without the prior written permission of National Journal Group. The use of copyrighted materials and/or images belonging to unrelated parties and reproduced herein is permitted pursuant to license and/or 17 USC § 107. Questions concerning use of these materials should be directed to: Alisha Johnson Associate Publisher National Journal Group The Watergate 600 New Hampshire Avenue, NW Washington, DC 20037 Phone: 202-266-7312 Fax: 202-266-7320 Email: [email protected] © 2009 National Journal Group All Rights Reserved. Washington in the Information Age i Statement of Purpose In 2002 and again in 2007, National Journal Group’s Washington in the Information Age chronicled how “Washington Insiders” were navigating the fast-changing media landscape. The 2002 study focused on the impact of the Internet on Washington’s media-consumption habits, while the 2007 report explored the Internet’s role as a gateway to content originating in other media platforms, such as television, radio and print. If anything, the pace of change in the media has accelerated in the two years since the completion of the 2007 report. -

Reagan, Challenger, and the Nation by Kristen

On A Frigid January Day in Central Florida: Reagan, Challenger, and the Nation By Kristen Soltis Anderson Space Shuttle launches are exhilarating to behold. They are grand spectacles, loud and unapologetic. For those up close, observing from the grounds of Kennedy Space Center in Florida, the rumble of the rocket engines is deafening. Hundreds of miles away, the growing trail of white exhaust topped by a small gleaming dot can be seen brightly, climbing silently into the sky. Whether watching with one’s own eyes or through a television broadcast, any launch of humans into space is a majestic and terrifying thing to behold. There is nothing routine, nothing ordinary about space. Yet on a frigid January day in Central Florida in 1986, the launch of the Space Shuttle Challenger was expected to be just that: routine. So “routine”, according to NBC news coverage, that “the Soviet Union reportedly didn't have its usual spy trawler anchored off the coast”.1 Two dozen previous Space Shuttle missions had taken off from American soil and returned home safely; there was little reason for Americans to think this mission would be any different. Though most Americans were not watching the launch live, one very special group of Americans was: schoolchildren. Despite the otherwise ordinary nature of the launch planned for that day, what did make the Challenger’s tenth mission special was the presence of Christa McAuliffe, a social studies teacher from New Hampshire. President Ronald Reagan had hoped that including a teacher in a shuttle mission would be an uplifting and inspirational reminder to the nation about the importance of education - and of our space program.