Judge Dredd: Hollywood Fiction Or Las Vegas Reality?

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Dragon Magazine

DRAGON 1 Publisher: Mike Cook Editor-in-Chief: Kim Mohan Shorter and stronger Editorial staff: Marilyn Favaro Roger Raupp If this isnt one of the first places you Patrick L. Price turn to when a new issue comes out, you Mary Kirchoff may have already noticed that TSR, Inc. Roger Moore Vol. VIII, No. 2 August 1983 Business manager: Mary Parkinson has a new name shorter and more Office staff: Sharon Walton accurate, since TSR is more than a SPECIAL ATTRACTION Mary Cossman hobby-gaming company. The name Layout designer: Kristine L. Bartyzel change is the most immediately visible The DRAGON® magazine index . 45 Contributing editor: Ed Greenwood effect of several changes the company has Covering more than seven years National advertising representative: undergone lately. in the space of six pages Robert Dewey To the limit of this space, heres some 1409 Pebblecreek Glenview IL 60025 information about the changes, mostly Phone (312)998-6237 expressed in terms of how I think they OTHER FEATURES will affect the audience we reach. For a This issues contributing artists: specific answer to that, see the notice Clyde Caldwell Phil Foglio across the bottom of page 4: Ares maga- The ecology of the beholder . 6 Roger Raupp Mary Hanson- Jeff Easley Roberts zine and DRAGON® magazine are going The Nine Hells, Part II . 22 Dave Trampier Edward B. Wagner to stay out of each others turf from now From Malbolge through Nessus Larry Elmore on, giving the readers of each magazine more of what they read it for. Saved by the cavalry! . 56 DRAGON Magazine (ISSN 0279-6848) is pub- I mention that change here as an lished monthly for a subscription price of $24 per example of what has happened, some- Army in BOOT HILL® game terms year by Dragon Publishing, a division of TSR, Inc. -

Magazines V17N9.Qxd

Apr COF C1:Customer 3/8/2012 3:24 PM Page 1 ORDERS DUE th 18APR 2012 APR E E COMIC H H T T SHOP’S CATALOG IFC Darkhorse Drusilla:Layout 1 3/8/2012 12:24 PM Page 1 COF Gem Page April:gem page v18n1.qxd 3/8/2012 11:16 AM Page 1 THE MASSIVE #1 STAR WARS: KNIGHT DARK HORSE COMICS ERRANT— ESCAPE #1 (OF 5) DARK HORSE COMICS BEFORE WATCHMEN: MINUTEMEN #1 DC COMICS MARS ATTACKS #1 IDW PUBLISHING AMERICAN VAMPIRE: LORD OF NIGHTMARES #1 DC COMICS / VERTIGO PLANETOID #1 IMAGE COMICS SPAWN #220 SPIDER-MEN #1 IMAGE COMICS MARVEL COMICS COF FI page:FI 3/8/2012 11:40 AM Page 1 FEATURED ITEMS COMICS & GRAPHIC NOVELS Strawberry Shortcake Volume 2 #1 G APE ENTERTAINMENT The Art of Betty and Veronica HC G ARCHIE COMIC PUBLICATIONS Bleeding Cool Magazine #0 G BLEEDING COOL 1 Radioactive Man: The Radioactive Repository HC G BONGO COMICS Prophecy #1 G D. E./DYNAMITE ENTERTAINMENT Pantha #1 G D. E./DYNAMITE ENTERTAINMENT 1 Power Rangers Super Samurai Volume 1: Memory Short G NBM/PAPERCUTZ Bad Medicine #1 G ONI PRESS Atomic Robo and the Flying She-Devils of the Pacific #1 G RED 5 COMICS Alien: The Illustrated Story Artist‘s Edition HC G TITAN BOOKS Alien: The Illustrated Story TP G TITAN BOOKS The League of Extraordinary Gentlemen III: Century #3: 2009 G TOP SHELF PRODUCTIONS Harbinger #1 G VALIANT ENTERTAINMENT LLC Winx Club Volume 1 GN G VIZ MEDIA BOOKS & MAGAZINES Flesk Prime HC G ART BOOKS DC Chess Figurine Collection Magazine Special #1: Batman and The Joker G COMICS Amazing Spider-Man Kit G COMICS Superman: The High Flying History of America‘s Most Enduring -

Dragon Magazine #120

Magazine Issue #120 Vol. XI, No. 11 SPECIAL ATTRACTIONS April 1987 9 PLAYERS HANDBOOK II: Publisher The ENRAGED GLACIERS & GHOULS games first volume! Mike Cook Six bizarre articles by Alan Webster, Steven P. King, Rick Reid, Jonathan Edelstein, and Editor James MacDougall. Roger E. Moore 20 The 1987 ORIGINS AWARDS BALL0T: A special but quite serious chance to vote for the best! Just clip (or copy) and mail! Assistant editor Fiction editor Robin Jenkins Patrick L. Price OTHER FEATURES Editorial assistants 24 Scorpion Tales Arlan P. Walker Marilyn Favaro Barbara G. Young A few little facts that may scare characters to death. Eileen Lucas Georgia Moore 28 First Impressions are Deceiving David A. Bellis Art director The charlatan NPC a mountebank, a trickster, and a DMs best friend. Roger Raupp 33 Bazaar of the Bizarre Bill Birdsall Three rings of command for any brave enough to try them. Production Staff 36 The Ecology of the Gas Spore Ed Greenwood Kim Lindau Gloria Habriga It isnt a beholder, but it isnt cuddly, either. Subscriptions Advertising 38 Higher Aspirations Mark L. Palmer Pat Schulz Mary Parkinson More zero-level spells for aspiring druids. 42 Plane Speaking Jeff Grubb Creative editors Tuning in to the Outer Planes of existence. Ed Greenwood Jeff Grubb 46 Dragon Meat Robert Don Hughes Contributing artists What does one do with a dead dragon in the front yard? Linda Medley Timothy Truman 62 Operation: Zenith Merle M. Rasmussen David E. Martin Larry Elmore The undercover war on the High Frontier, for TOP SECRET® game fans. Jim Holloway Marvel Bullpen Brad Foster Bruce Simpson 64 Space-Age Espionage John Dunkelberg, Jr. -

Portland Daily Press: December 25, 1878

PORTLAND DAILY PRESS. ESTABLISHED JUNE 23, 1862.—YOL. 16. PORTLAND, WEDNESDAY MORNING. DECEMBER 25, 1878. TERMS $8.00 PER ANNUM, IN ADYANCE. TDE PORTLAND DAILY PRESS, MISCELLANEOUS. The Yule Festival. Men and Women. Published I THE PRESS. every day (Sundays excepted) by the _MISCELLANEOUS. The Mother Church in pursuance of her While teaching the young idea of Master PORTLAND wise policy of taking the wherever It John Qainn, of Vernon, Vt, how to shoot with PUBLISHING CO, WEDNESDAY MORNING, DEC. 25. good can be fonnd has made tbe old a Mrs. Bosworth shot At 119 Exchange St., Portland. of Fagan revolver, the child, who USEFUL ARTICLES feasts held in celebration oi the Winter did not know she was loaded with cider. Terms : Eight Dollars a Tear. To mail subscribers We do not read anonymous letters and commun] Dollars a Tear if Insurance. A in Seven paid in advance. no clergyman Ken- cations. The name and addresB of the writer are in Solstice a Christian testival. There is Washington county, tucky, reads the service with such all cases indispensable, not necessarily for publication warrant in history or the earliest tradition marriage THE MAINE STATE PRESS FOR power that a but as a guaranty of good faith. for the birth of Christ to the 25th susceptible reporter says the sa- is published every Thursday Morning at $2.50 a assigning cred tie We cannot undertake to retnrn or preserve com- seemed to be “graven with pen of Iron year, it paid iu advance at $2.00 a year. of December; but as early as the fourth cen- munications that are not nsed. -

Ventura College Associate Vice Chancellor Information Technology 4667 Telegraph Road, Ventura, CA 93003 Mr

2005 • 2006 General Catalog The Community Colleges of and Ventura County District Board of Trustees Announcement of Courses Area 1 Ms. Mary Anne Rooney, Trustee Area 2 Ms. Cheryl Heitmann, Vice President Area 3 Dr. Larry O. Miller, Trustee Area 4 Robert O. Huber, Esq., Trustee Area 5 Mr. Arturo D. Hernández, Trustee Student Trustee Fall election scheduled District Administrators Chancellor Chief Executive Officer Dr. James M. Meznek Deputy Chancellor Mr. Michael Gregoryk Vice Chancellor Human Resources Mr. William Studt Graduation 2005 Associate Vice Chancellor Human Resources Ms. Patricia Parham Ventura College Associate Vice Chancellor Information Technology 4667 Telegraph Road, Ventura, CA 93003 Mr. Vic Belinski (805) 654-6400, 986-5855, 378-1500, 656-0546 Associate Vice Chancellor www.venturacollege.edu Business Services/ Financial Management Ventura College is accredited by the Accrediting Commission for Community and Ms. Sue Johnson Junior Colleges of the Western Association of Schools and Colleges, 10 Commercial Boulevard, Suite 204, Novato, CA 94949, (415) 506-0234, an institutional accrediting body recognized by the Council for Higher Education Accreditation and the U.S. College Administrators Department of Education. President, Moorpark College The College Catalog is available in alternate formats upon request from the Dr. Eva Conrad Educational Assistance Center, (805) 654-6300. President, Oxnard College Ventura College has made every reasonable effort to insure that the information provided in this general Dr. Lydia Ledesma-Reese Catalog is accurate and current. However, this document should not be considered an irrevocable contract between the student and Ventura College. The content is subject to change. The College reserves the right to make additions, revisions, or deletions as may be necessary due to changes in governmental regulations, President, Ventura College district policy, or college policy, procedures, or curriculum. -

The Bates Student

Bates College SCARAB The aB tes Student Archives and Special Collections 1-9-1920 The aB tes Student - Magazine Section - volume 48 number 01 - January 9, 1920 Bates College Follow this and additional works at: http://scarab.bates.edu/bates_student Recommended Citation Bates College, "The aB tes Student - Magazine Section - volume 48 number 01 - January 9, 1920" (1920). The Bates Student. 545. http://scarab.bates.edu/bates_student/545 This Newspaper is brought to you for free and open access by the Archives and Special Collections at SCARAB. It has been accepted for inclusion in The aB tes Student by an authorized administrator of SCARAB. For more information, please contact [email protected]. ;: 11 :;i s re, Zr MIR SOW tJanuary JSumber 1920 " %1 i PAGE Editorials: <. The Gentle Art of Dodging' What We Have To Read Mumps Eva B. Symmes, '20 Lonesome Pete Irma Haskell, '21 A Departmental War Worker Carl E. Purinton, '23 The Silent Will 10 Harold Manter, '22 A Strike That Told 15 Frances Field Air Castles 19 Amy V. Blaisdell, '23 Back Door Callers 20 Marguerite Hill, '21 In the Nick of Time 24 Dwight Libby, '22 Too Good To Keep 30 BENSON & WHITE, Insurance AGENCY ESTABLISHED 1857 Insurance of all Kinds Written at Current Rates 165 Main Street, - - LEWISTON, MAINE Photographs that Please MORRELL & PRINCE AT THE NEW Shoe Dealers HAMMOND STUDIO Reduced Rates to Graduates HAMMOND BROS. 13 Lisbon St., Lewiston, Me. 138 Lisbon St., LEWISTON, ME. Ask for Students' Discount THE FISK TEACHERS' AGENCY Everett O. Fisk & Co., Proprietors Boston, Mass., 2a Park Street Chicago, 111., 28 E. -

British Writers, DC, and the Maturation of American Comic Books Derek Salisbury University of Vermont

University of Vermont ScholarWorks @ UVM Graduate College Dissertations and Theses Dissertations and Theses 2013 Growing up with Vertigo: British Writers, DC, and the Maturation of American Comic Books Derek Salisbury University of Vermont Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.uvm.edu/graddis Recommended Citation Salisbury, Derek, "Growing up with Vertigo: British Writers, DC, and the Maturation of American Comic Books" (2013). Graduate College Dissertations and Theses. 209. https://scholarworks.uvm.edu/graddis/209 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Dissertations and Theses at ScholarWorks @ UVM. It has been accepted for inclusion in Graduate College Dissertations and Theses by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks @ UVM. For more information, please contact [email protected]. GROWING UP WITH VERTIGO: BRITISH WRITERS, DC, AND THE MATURATION OF AMERICAN COMIC BOOKS A Thesis Presented by Derek A. Salisbury to The Faculty of the Graduate College of The University of Vermont In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements For the Degree of Master of Arts Specializing in History May, 2013 Accepted by the Faculty of the Graduate College, The University of Vermont, in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts, specializing in History. Thesis Examination Committee: ______________________________________ Advisor Abigail McGowan, Ph.D ______________________________________ Melanie Gustafson, Ph.D ______________________________________ Chairperson Elizabeth Fenton, Ph.D ______________________________________ Dean, Graduate College Domenico Grasso, Ph.D March 22, 2013 Abstract At just under thirty years the serious academic study of American comic books is relatively young. Over the course of three decades most historians familiar with the medium have recognized that American comics, since becoming a mass-cultural product in 1939, have matured beyond their humble beginnings as a monthly publication for children. -

Woeful Delights Forensic Science at the Cinema, the Sequel James E

v5n4.book Page 407 Friday, June 28, 2002 9:19 PM More Woeful Delights Forensic Science at the Cinema, The Sequel James E. Starrs icking up where we left oÖ, see Woeful space and on earth, even under the pressure of Delights, 4 Green Bag 2d 409 (2001), at gravity. Gravity, or the lack of it, has no eÖect Pthe end of Category 2: Hollywood Just on the geometric shape of liquid droplets. Frolics With Science … With or without gravity such droplets are round balls, not tear-shaped, a vitally impor- Category 3: Hollywood Hits tant recognition in crime scene reconstruc- the Scientific Mark tions from the interpretation of blood spattering. Sometimes, but only rarely, Hollywood gives Two true-to-forensic science movies are forensic science the beneÕt of the doubt and Call Northside 777 with Jimmy Stewart and Lee presents it in a credible fashion. Arguably J. Cobb and Allegheny Uprising with John Hollywood can produce Õlms with forensic Wayne and Claire Trevor. Unfortunately for science depicted accurately without sacriÕcing today’s movie-goers both of these Õlms are the interest of the viewer in the unfolding dated, the Õrst having hit the silver screen in drama. 1948 and the latter even earlier, in 1939. In Star Trek VI: The Undiscovered Country (1991), for example, two assassins board a space Call Northside 777 (1948) – vehicle, disabled in zero gravity conditions, Photography and send blood Ôying as they shoot up every- Jimmy Stewart, playing a Chicago reporter, one in sight. The shape of the blood drops is needed considerable convincing to believe that spherical in nature as it should be both in Frank Wiecek, acted by Richard Conte, was James E. -

January 25,1917

Rep._~ _ Journal. JANUARY BELFAST, MAINE, THURSDAY, 25, 1917. NUMBER 4 s £ ,, Today Jcuina1. The funeral of the late OBITUARY. Charles H. Sargen NEWS OF >"”> took Notes. THE GRANGES. place at bis late home, No. 46 Cede: Legislative Belfast Free to Library. .. ,r 1 doing Germany., atreet. at 2 PERSONAL. Ed for 35 a Friday p. m„ Rev. J. Wilbor C hurches. .Secret So White, aged 70, years resident o Rich. Comet Grange, Swanville, held an it; ardson of the the Governor and alhday u' Breckenridge. died suddenly while at breakfast the church At hearing before c Notes. News ol Baptiat as session Jan were NEW Mrs. H. V..fislatwe last in officiating, 16th and their officers in- BOOKS. JANUARY, 1917. J. Morris h*s returned from a viait in Real Es- Saturday morning the dining room of sisted by H. Council in Augusta last Friday afternoon Transfers Harry Upton of Colby College stalled in Boston and the Denver hotel. He had arisen at his usual Who he by District Deputy Edward Evans of vicinity. [ Bosket Ball. ..Th« at the requeat of the Clarence Higgins said that wished tb hour, and appeared in normal health, though family sang Mr Belfast, assisted Mr. and Mrs. Fred Nicker- l ibrary. state that the by Mrs. A E. Greenlaw of Camden is the |.;. before seating himself at the breakfast Sargent's favorite hymn, “Face to to all parties interested appro- Missions. guest table, Face.' son of Monroe, in an able and of Mr. 5 rd Letter..Pick* he had of not The bearers State-aided in- very pleasing and Mrs. -

EXECUTIVE SUMMARY Decapitation

EXECUTIVE SUMMARY Decapitation. Dismemberment. Serial killers. Graphic gore. Hey, Kids! COMICS!! Since the release of The Dark Knight film series and the 22 movies in the Marvel Cinematic Universe, comic-book characters have become wildly popular in other forms of entertainment, particularly television. But broadcast TV’s representations of comic-book characters are no longer the bright, colorful, and optimistic figures of the past. Children are innately attracted to comic-book characters; but in today’s comic book-based programs, children are being exposed to graphic violence, profanity, dark and intense themes, and other inappropriate content. In this research report, the PTC examined comic book-themed prime-time programming on the maJor broadcast networks during November, February, and May “sweeps” periods from November 2012 through May 2019. Programs examined were Fox’s Gotham; CW’s Arrow, Black Lightning, The Flash, Supergirl, DC’s Legends oF Tomorrow, and Riverdale; and ABC’s Marvel’s Agents oF S.H.I.E.L.D., Marvel’s Agent Carter, and Marvel’s Inhumans. Research data suggest that broadcast television programs based on these comic-book characters, created and intended for children, are increasingly inappropriate and/or unsafe for young viewers. In its research, the PTC found the following during the study period: • In comic book-themed programming with particular appeal to children, young viewers were exposed to over 6,000 incidents of violence, over 500 deaths, and almost 2,000 profanities. • The most violent program was CW’s Arrow. Young viewers witnessed 1,241 acts of violence, including 310 deaths, 280 instances of gun violence, and 26 scenes of people being tortured. -

Texas Disapproved Publication

TEXAS DEPT. OF CRIMINAL JUSTICE DISAPPROVED PUBLICATIONS - January - December 2018 Date Publication Title Author(s) Year of Publication ISBN Issue Disapproved Pages Rejection Reason 1/2/2018 Criminal: Coward Ed Brubaker 2016 9781632151704 72 SEI 1/2/2018 Badlands Steven Grant 1993 9781878574534 22, 41, 53 SEI 1/2/2018 Strike Magazine Autumn 2017 N19 41, 43 SEI 1/2/2018 303 Squadron Arkady Fielder 2010 9781607720041 Approved N/A 1/3/2018 Popular Mechanics 14-Feb V194 N11 79 BRK WPN 1/3/2018 International Tattoo Art Sep-96 2, 41 SEI 1/3/2018 International Tattoo Art Jul-96 24,42 SEI 1/3/2018 International Tattoo Art Jan-97 26, 49 SEI 1/3/2018 Image+ 11/2017, 1/2018 V2 N3 27, 30 SEI 1/3/2018 International Tattoo Art May-96 3,4 SEI 1/3/2018 Take What You Can…Give Nothing Back Martin LaCasse 2010 9780982404720 8, 48, 146 SEI 1/3/2018 W Magazine 14-Dec V46, N10 96, 97 SEI 1/3/2018 Wendy's Got the Heat Wendy Williams 2003 74370214 Approved N/A 1/5/2018 Oral Sex for Everybody Tina Robbins 2014 9781629144764 100, 101 SEI 1/10/2018 Marshal Law Pat Mills 2014 9781401251406 11, 14 SEI 1/11/2018 Hand Lettering and Contemporary Calligraphy Lisa Engelbrecht 2018 9780785835257 138 SEI 1/11/2018 US Marine Close Combat Fighting Handbook Jack Hoban 2010 9781616081072 1-1, 1-2, 1-6, 2-2, 2-3, 2-4, 2-6 OFF/DEF fighting tech 1/12/2018 Master of the Game Sidney Sheldon 1982 9781478948421 354 Rape 1/12/2018 Neon Genesis Evangelion 4,5,6 Yoshiyuki Sadamoto 2013 9781421553054 401 SEI 1/12/2018 A Guide to Improvised Weaponry Terry Schappert 2015 9781440584725 16-Nov Self Defese Techniques 1/12/2018 Hacking Electronics 2nd Edition Simon Monk 2017 9781560012200 14, 86-92 how to hack computers and override electrical circuits 1/12/2018 Great American Adventure Judge Dale 1933 none Approved N/A 1/12/2018 It Can Happen in a Minute S.M. -

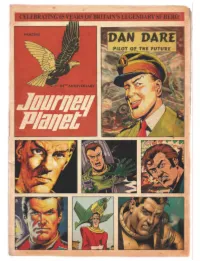

Journey Planet 24 - June 2015 James Bacon ~ Michael Carroll ~ Chris Garcia Great Newseditors Chums! The

I I • • • 1 JOURNEY PLANET 24 - JUNE 2015 JAMES BACON ~ MICHAEL CARROLL ~ CHRIS GARCIA GREAT NEWSEDITORS CHUMS! THE Dan Dare and related characters are (C) the Dan Dare Corporation. All other illustrations and photographs are (C) their original creators. Table of Contents Page 3 - Some Years in the Future - An Editorial by Michael Carroll Dan Dare in Print Page 6 - The Rise and Fall of Frank Hampson: A Personal View by Edward James Page 9 - The Crisis of Multiple Dares by David MacDonald Page 11 - A Whole New Universe to Master! - Michael Carroll looks back at the 2000AD incarnation of Dan Dare Page 15 - Virgin Comics’ Dan Dare by Gary Eskine Page 17 - Bryan Talbot Interviewed by James Bacon Page 19 - Making the Old New Again by Dave Hendrick Page 21 - 65 Years of Dan Dare by Barrie Tomlinson Page 23 - John Higgins on Dan Dare Page 26 - Richard Bruton on Dan Dare Page 28 - Truth or Dare by Peppard Saltine Page 31 - The Bidding War for the 1963 Dan Dare Annual by Steve Winders Page 33 - Dan Dare: My Part in His Revival by Pat Mills Page 36 -Great News Chums! The Eagle Family Tree by Jeremy Briggs Dan Dare is Everywhere! Page 39 - Dan Dare badge from Bill Burns Page 40 - My Brother the Mekon and Other Thrilling Space Stories by Helena Nash Page 45 - Dan Dare on the Wireless by Steve Winders Page 50 - Lego Dan Dare by James Shields Page 51 - The Spacefleet Project by Dr. Raymond D. Wright Page 54 - Through a Glass Darely: Ministry of Space by Helena Nash Page 59 - Dan Dare: The Video Game by James Shields Page 61 - Dan Dare vs.