”Arpeggione” Sonata

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Evolution of the Clarinet and Its Effect on Compositions Written for the Instrument

Columbus State University CSU ePress Theses and Dissertations Student Publications 5-2016 The Evolution of the Clarinet and Its Effect on Compositions Written for the Instrument Victoria A. Hargrove Follow this and additional works at: https://csuepress.columbusstate.edu/theses_dissertations Part of the Music Commons Recommended Citation Hargrove, Victoria A., "The Evolution of the Clarinet and Its Effect on Compositions Written for the Instrument" (2016). Theses and Dissertations. 236. https://csuepress.columbusstate.edu/theses_dissertations/236 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Publications at CSU ePress. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of CSU ePress. THE EVOLUTION OF THE CLARINET AND ITS EFFECT ON COMPOSITIONS WRITTEN FOR THE INSTRUMENT Victoria A. Hargrove COLUMBUS STATE UNIVERSITY THE EVOLUTION OF THE CLARINET AND ITS EFFECT ON COMPOSITIONS WRITTEN FOR THE INSTRUMENT A THESIS SUBMITTED TO HONORS COLLEGE IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE HONORS IN THE DEGREE OF BACHELOR OF MUSIC SCHWOB SCHOOL OF MUSIC COLLEGE OF THE ARTS BY VICTORIA A. HARGROVE THE EVOLUTION OF THE CLARINET AND ITS EFFECT ON COMPOSITIONS WRITTEN FOR THE INSTRUMENT By Victoria A. Hargrove A Thesis Submitted to the HONORS COLLEGE In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for Honors in the Degree of BACHELOR OF MUSIC PERFORMANCE COLLEGE OF THE ARTS Thesis Advisor Date ^ It, Committee Member U/oCWV arcJc\jL uu? t Date Dr. Susan Tomkiewicz A Honors College Dean ABSTRACT The purpose of this lecture recital was to reflect upon the rapid mechanical progression of the clarinet, a fairly new instrument to the musical world and how these quick changes effected the way composers were writing music for the instrument. -

The Total Work of Art in European Modernism Series Editor: Peter Uwe Hohendahl, Cornell University

The Total Work of Art in European Modernism Series editor: Peter Uwe Hohendahl, Cornell University Signale: Modern German Letters, Cultures, and Thought publishes new English- language books in literary studies, criticism, cultural studies, and intellectual history pertaining to the German-speaking world, as well as translations of im- portant German-language works. Signale construes “modern” in the broadest terms: the series covers topics ranging from the early modern period to the present. Signale books are published under a joint imprint of Cornell University Press and Cornell University Library in electronic and print formats. Please see http://signale.cornell.edu/. The Total Work of Art in European Modernism David Roberts A Signale Book Cornell University Press and Cornell University Library Ithaca, New York Cornell University Press and Cornell University Library gratefully acknowledge the support of The Andrew W. Mellon Foundation for the publication of this volume. Copyright © 2011 by Cornell University All rights reserved. Except for brief quotations in a review, this book, or parts thereof, must not be reproduced in any form without permission in writ- ing from the publisher. For information, address Cornell University Press, Sage House, 512 East State Street, Ithaca, New York 14850. First published 2011 by Cornell University Press and Cornell University Library Printed in the United States of America Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Roberts, David, 1937– The total work of art in European modernism / David Roberts. p. cm. — (Signale : modern German letters, cultures, and thought) Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 978-0-8014-5023-5 (pbk. : alk. paper) 1. Modernism (Aesthetics) 2. -

The String Quartets of George Onslow First Edition

The String Quartets of George Onslow First Edition All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. Published in the United States by Edition Silvertrust a division of Silvertrust and Company Edition Silvertrust 601 Timber Trail Riverwoods, Illinois 60015 USA Website: www.editionsilvertrust.com For Loren, Skyler and Joyce—Onslow Fans All © 2005 R.H.R. Silvertrust 1 Table of Contents Introduction & Acknowledgements ...................................................................................................................3 The Early Years 1784-1805 ...............................................................................................................................5 String Quartet Nos.1-3 .......................................................................................................................................6 The Years between 1806-1813 ..........................................................................................................................10 String Quartet Nos.4-6 .......................................................................................................................................12 String Quartet Nos. 7-9 ......................................................................................................................................15 String Quartet Nos.10-12 ...................................................................................................................................19 The Years from 1813-1822 ...............................................................................................................................22 -

RUSSIAN, SOVIET & POST-SOVIET SYMPHONIES Composers

RUSSIAN, SOVIET & POST-SOVIET SYMPHONIES A Discography of CDs and LPs Prepared by Michael Herman Composers A-G KHAIRULLO ABDULAYEV (b. 1930, TAJIKISTAN) Born in Kulyab, Tajikistan. He studied composition at the Moscow Conservatory under Anatol Alexandrov. He has composed orchestral, choral, vocal and instrumental works. Sinfonietta in E minor (1964) Veronica Dudarova/Moscow State Symphony Orchestra ( + Poem to Lenin and Khamdamov: Day on a Collective Farm) MELODIYA S10-16331-2 (LP) (1981) LEV ABELIOVICH (1912-1985, BELARUS) Born in Vilnius, Lithuania. He studied at the Warsaw Conservatory and then at the Minsk Conservatory where he studied under Vasily Zolataryov. After graduation from the latter institution, he took further composition courses with Nikolai Miaskovsky at the Moscow Conservatory. He composed orchestral, vocal and chamber works. His other Symphonies are Nos. 1 (1962), 3 in B flat minor (1967) and 4 (1969). Symphony No. 2 in E minor (1964) Valentin Katayev/Byelorussian State Symphony Orchestra ( + Vagner: Suite for Symphony Orchestra) MELODIYA D 024909-10 (LP) (1969) VASIF ADIGEZALOV (1935-2006, AZERBAIJAN) Born in Baku, Azerbaijan. He studied under Kara Karayev at the Azerbaijan Conservatory and then joined the staff of that school. His compositional catalgue covers the entire range of genres from opera to film music and works for folk instruments. Among his orchestral works are 4 Symphonies of which the unrecorded ones are Nos. 1 (1958) and 4 "Segah" (1998). Symphony No. 2 (1968) Boris Khaikin/Moscow Radio Symphony Orchestra (rec. 1968) ( + Piano Concertos Nos. 2 and 3, Poem Exaltation for 2 Pianos and Orchestra, Africa Amidst MusicWeb International Last updated: August 2020 Russian, Soviet & Post-Soviet Symphonies A-G Struggles, Garabagh Shikastasi Oratorio and Land of Fire Oratorio) AZERBAIJAN INTERNATIONAL (3 CDs) (2007) Symphony No. -

Schubert's!Voice!In!The!Symphonies!

! ! ! ! A!Search!for!Schubert’s!Voice!in!the!Symphonies! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! Camille!Anne!Ramos9Klee! ! Submitted!to!the!Department!of!Music!of!Amherst!College!in!partial!fulfillment! of!the!requirements!for!the!degree!of!Bachelor!of!Arts!with!honors! ! Faculty!Advisor:!Klara!Moricz! April!16,!2012! ! ! ! ! ! In!Memory!of!Walter!“Doc”!Daniel!Marino!(191291999),! for!sharing!your!love!of!music!with!me!in!my!early!years!and!always!treating!me!like! one!of!your!own!grandchildren! ! ! ! ! ! ! Table!of!Contents! ! ! Introduction! Schubert,!Beethoven,!and!the!World!of!the!Sonata!! 2! ! ! ! Chapter!One! Student!Works! 10! ! ! ! Chapter!Two! The!Transitional!Symphonies! 37! ! ! ! Chapter!Three! Mature!Works! 63! ! ! ! Bibliography! 87! ! ! Acknowledgements! ! ! First!and!foremost!I!would!like!to!eXpress!my!immense!gratitude!to!my!advisor,! Klara!Moricz.!This!thesis!would!not!have!been!possible!without!your!patience!and! careful!guidance.!Your!support!has!allowed!me!to!become!a!better!writer,!and!I!am! forever!grateful.! To!the!professors!and!instructors!I!have!studied!with!during!my!years!at! Amherst:!Alison!Hale,!Graham!Hunt,!Jenny!Kallick,!Karen!Rosenak,!David!Schneider,! Mark!Swanson,!and!Eric!Wubbels.!The!lessons!I!have!learned!from!all!of!you!have! helped!shape!this!thesis.!Thank!you!for!giving!me!a!thorough!music!education!in!my! four!years!here!at!Amherst.! To!the!rest!of!the!Music!Department:!Thank!you!for!creating!a!warm,!open! environment!in!which!I!have!grown!as!both!a!student!and!musician.!! To!the!staff!of!the!Music!Library!at!the!University!of!Minnesota:!Thank!you!for! -

Schubert's Mature Operas: an Analytical Study

Durham E-Theses Schubert's mature operas: an analytical study Bruce, Richard Douglas How to cite: Bruce, Richard Douglas (2003) Schubert's mature operas: an analytical study, Durham theses, Durham University. Available at Durham E-Theses Online: http://etheses.dur.ac.uk/4050/ Use policy The full-text may be used and/or reproduced, and given to third parties in any format or medium, without prior permission or charge, for personal research or study, educational, or not-for-prot purposes provided that: • a full bibliographic reference is made to the original source • a link is made to the metadata record in Durham E-Theses • the full-text is not changed in any way The full-text must not be sold in any format or medium without the formal permission of the copyright holders. Please consult the full Durham E-Theses policy for further details. Academic Support Oce, Durham University, University Oce, Old Elvet, Durham DH1 3HP e-mail: [email protected] Tel: +44 0191 334 6107 http://etheses.dur.ac.uk Schubert's Mature Operas: An Analytical Study Richard Douglas Bruce Submitted for the Degree of PhD October 2003 University of Durham Department of Music A copyright of this thesis rests with the author. No quotation from it should be published without his prior written consent and information derived from it should be acknowledged. The copyright of this thesis rests with the author. No quotation from it should be published without their prior written consent and information derived from it should be acknowledged. 2 3 JUN 2004 Richard Bruce - Schubert's Mature Operas: An Analytical Study Submitted for the degree of Ph.D (2003) (Abstract) This thesis examines four of Franz Schubert's complete operas: Die Zwillingsbruder D.647, Alfonso und Estrella D.732, Die Verschworenen D.787, and Fierrabras D.796. -

Verdi Falstaff

Table of Opera 101: Getting Ready for the Opera 4 A Brief History of Western Opera 6 Philadelphia’s Academy of Music 8 Broad Street: Avenue of the Arts Con9tOperae Etiquette 101 nts 10 Why I Like Opera by Taylor Baggs Relating Opera to History: The Culture Connection 11 Giuseppe Verdi: Hero of Italy 12 Verdi Timeline 13 Make Your Own Timeline 14 Game: Falstaff Crossword Puzzle 16 Bard of Stratford – William Shakespeare 18 All the World’s a Stage: The Globe Theatre Falstaff: Libretto and Production Information 20 Falstaff Synopsis 22 Meet the Artists 23 Introducing Soprano Christine Goerke 24 Falstaff LIBRETTO Behind the Scenes: Careers in the Arts 65 Game: Connect the Opera Terms 66 So You Want to Sing Like an Opera Singer! 68 The Highs and Lows of the Operatic Voice 70 Life in the Opera Chorus: Julie-Ann Whitely 71 The Subtle Art of Costume Design Lessons 72 Conflicts and Loves in Falstaff 73 Review of Philadelphia’s First Falstaff 74 2006-2007 Season Subscriptions Glossary 75 State Standards 79 State Standards Met 80 A Brief History of 4 Western Opera Theatrical performances that use music, song Music was changing, too. and dance to tell a story can be found in many Composers abandoned the ornate cultures. Opera is just one example of music drama. Baroque style of music and began Claudio Monteverdi In its 400-year history opera has been shaped by the to write less complicated music 1567-1643 times in which it was created and tells us much that expressed the character’s thoughts and feelings about those who participated in the art form as writers, more believably. -

1 Ludwig Van Beethoven Symphony #9 in D Minor, Op. 125 2 Johann Sebastian Bach St. Matthew Passion

1 Ludwig van Beethoven Symphony #9 in D minor, Op. 125 2 Johann Sebastian Bach St. Matthew Passion "Ebarme dich, mein Gott" 3 George Frideric Handel Messiah: Hallelujah Chorus 4 Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart Symphony 41 C, K.551 "Jupiter" 5 Samuel Barber Adagio for Strings Op.11 6 Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart Clarinet Concerto A, K.622 7 Ludwig van Beethoven Piano Concerto 5 E-Flat, Op.73 "Emperor" (3) 8 Antonin Dvorak Symphony No 9 (IV) 9 George Gershwin Rhapsody In Blue (1924) 10 Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart Requiem in D minor K 626 (aeternam/kyrie/lacrimosa) 11 George Frideric Handel Xerxes - Largo 12 Johann Sebastian Bach Toccata And Fugue In D Minor, BWV 565 (arr Stokowski) 13 Ludwig van Beethoven Symphony No 5 in C minor Op 67 (I) 14 Johann Sebastian Bach Orchestral Suite #3 BWV 1068: Air on the G String 15 Antonio Vivaldi Concerto Grosso in E Op. 8/1 RV 269 "Spring" 16 Tomaso Albinoni Adagio in G minor 17 Edvard Grieg Peer Gynt 1, Op.46 18 Sergei Rachmaninov Piano Concerto No 2 in C minor Op 18 (I) 19 Ralph Vaughan Williams Lark Ascending 20 Gustav Mahler Symphony 5 C-Sharp Min (4) 21 Peter Ilyich Tchaikovsky 1812 Overture 22 Jean Sibelius Finlandia, Op.26 23 Johann Pachelbel Canon in D 24 Carl Orff Carmina Burana: O Fortuna, In taberna, Tanz 25 Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart Serenade G, K.525 "Eine Kleine Nachtmusik" 26 Johann Sebastian Bach Brandenburg Concerto No 5 in D BWV 1050 (I) 27 Johann Strauss II Blue Danube Waltz, Op.314 28 Franz Joseph Haydn Piano Trio 39 G, Hob.15-25 29 George Frideric Handel Water Music Suite #2 in D 30 Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart Ave Verum Corpus, K.618 31 Johannes Brahms Symphony 1 C Min, Op.68 32 Felix Mendelssohn Violin Concerto in E minor, Op. -

Eloquence Releases: Summer 2017 by Brian Wilson

Some Recent Eloquence Releases: Summer 2017 by Brian Wilson The original European Universal Eloquence label replaced budget releases on DG (Privilege or Resonance), Decca (Weekend Classics) and Philips (Classical Favourites). Like them it originally sold for around £5 and offered some splendid bargains such as Telemann’s ‘Water Music’ and excerpts from Tafelmusik (Musica Antiqua Köln/Reinhard Goebel 4696642) and Mahler’s Das Lied von der Erde (Janet Baker, James King, Concertgebouw/Bernard Haitink 4681822). Later most of the original batch were deleted – luckily the Mahler remains available – and production switched to Universal Australia but the price remained around the same. More recently changes in the value of the £ mean that single CDs now sell for around £7.75 but the high quality of much of the repertoire means that they remain well worth keeping an eye on. Many, but not all, of the albums are available to stream or download and I have reviewed some in that form and others on CD. Be aware, however, that the downloads often cost more than the CDs and invariably come without notes – which is a shame because the Eloquence booklets are better than those of many budget labels. THE TUDORS Lo, Country Sports Anonymous Almain Thomas TOMKINS Adieu, Ye City-Prisoning Towers Thomas WEELKES Lo, Country Sports that Seldom Fades Nicholas BRETON Shepherd and Shepherdess Michael EAST Sweet Muses, Nymphs and Shepherds Sporting Bar YOUNG The Shepherd, Arsilius’s, Reply John FARMER O Stay, Sweet Love Giles FARNABY Pearce did love fair Petronel Michael -

Euphonium Repertoire List Title Composer Arranger Grade Air Varie

Euphonium Repertoire List Title Composer Arranger Grade Air Varie Pryor Smith 1 Andante and Rondo Capuzzi Catelinet 1 Andante et Allegro Ropartz Shapiro 1 Andante et Allegro Barat 1 Arpeggione Sonata Schubert Werden 1 Beautiful Colorado DeLuca 1 Believe Me If All Those Endearing Young Charms Mantia Werden 1 Blue Bells of Scotland Pryor 1 Bride of the Waves Clarke 1 Buffo Concertante Jaffe Centone 1 Carnival of Venice Clark Brandenburg 1 Concert Fantasy Cords Laube 1 Concert Piece Nux 1 Concertino No. 1 in Bb Major Op. 7 Klengel 1 Concertino Op. 4 David 1 Concerto Capuzzi Baines 1 Concerto in a minor Vivaldi Ostrander 1 Concerto in Bb K.191 Mozart Ostrander 1 Eidolons for Euphonium and Piano Latham 1 Fantasia Jacob 1 Fantasia Di Concerto Boccalari 1 Fantasie Concertante Casterede 1 Fantasy Sparke 1 Five Pieces in Folk Style Schumann Droste 1 From the Shores of the Mighty Pacific Clarke 1 Grand Concerto Grafe Laude 1 Heroic Episode Troje Miller 1 Introduction and Dance Barat Smith 1 Largo and Allegro Marcello Merriman 1 Lyric Suite White 1 Mirror Lake Montgomery 1 Montage Uber 1 Morceau de Concert Saint-Saens Nelson 1 Euphonium Repertoire List Morceau Symphonique Op. 88 Guilmant 1 Napoli Bellstedt Simon 1 Nocturne and Rondolette Shepherd 1 Partita Ross 1 Piece en fa mineur Morel 1 Rhapsody Curnow 1 Rondo Capriccioso Spears 1 Sinfonia Pergolesi Sauer 1 Six Sonatas Volume I Galliard Brown 1 Six Sonatas Volume II Galliard Brown 1 Sonata Whear 1 Sonata Clinard 1 Sonata Besozzi 1 Sonata White 1 Sonata Euphonica Hartley 1 Sonata in a minor Marcello -

Concert Program

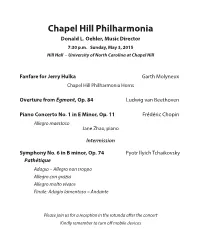

Chapel Hill Philharmonia Donald L. Oehler, Music Director 7:30 p.m. Sunday, May 3, 2015 Hill Hall – University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill Fanfare for Jerry Hulka Garth Molyneux Chapel Hill Philharmonia Horns Overture from Egmont, Op. 84 Ludwig van Beethoven Piano Concerto No. 1 in E Minor, Op. 11 Frédéric Chopin Allegro maestoso Jane Zhao, piano Intermission Symphony No. 6 in B minor, Op. 74 Pyotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky Pathétique Adagio – Allegro non troppo Allegro con grazia Allegro molto vivace Finale: Adagio lamentoso – Andante Please join us for a reception in the rotunda after the concert Kindly remember to turn off mobile devices Pathétique The Romantic era idealized heroes. The works on tonight’s Chapel Hill Philharmonia program comprise three dis- tinct takes on heroism—the martyrdom of a leader to the cause of freedom, the creativity of an artist in the face of an incurable illness, and the passionate suffering of an individual descending into silence. Fanfare for Jerry Hulka Jaroslav Hulka, M.D., passed away on November 24, 2014, at age 84. A founding member of the CHP and long time principal French horn player, Jerry also served the orchestra as a board member and president. He is survived by his wife Barbara Sorenson Hulka, a UNC-Chapel Hill professor emerita and former CHP concertmaster. The couple met as undergraduates when both were section princi- pals in the Harvard/Radcliffe Orchestra. The Hulkas have donated generously to the CHP and to classical music programs at UNC- Chapel Hill and throughout the Triangle. In his “day job” Jerry was a well-respected academic and obstetrics/gynecology specialist, recognized as a wise physician, mentor, and innovator. -

Britten Connections a Guide for Performers and Programmers

Britten Connections A guide for performers and programmers by Paul Kildea Britten –Pears Foundation Telephone 01728 451 700 The Red House, Golf Lane, [email protected] Aldeburgh, Suffolk, IP15 5PZ www.brittenpears.org Britten Connections A guide for performers and programmers by Paul Kildea Contents The twentieth century’s Programming tips for 03 consummate musician 07 13 selected Britten works Britten connected 20 26 Timeline CD sampler tracks The Britten-Pears Foundation is grateful to Orchestra, Naxos, Nimbus Records, NMC the following for permission to use the Recordings, Onyx Classics. EMI recordings recordings featured on the CD sampler: BBC, are licensed courtesy of EMI Classics, Decca Classics, EMI Classics, Hyperion Records, www.emiclassics.com For full track details, 28 Lammas Records, London Philharmonic and all label websites, see pages 26-27. Index of featured works Front cover : Britten in 1938. Photo: Howard Coster © National Portrait Gallery, London. Above: Britten in his composition studio at The Red House, c1958. Photo: Kurt Hutton . 29 Further information Opposite left : Conducting a rehearsal, early 1950s. Opposite right : Demonstrating how to make 'slung mugs' sound like raindrops for Noye's Fludde , 1958. Photo: Kurt Hutton. Britten Connections A guide for performers and programmers 03 The twentieth century's consummate musician In his tweed jackets and woollen ties, and When asked as a boy what he planned to be He had, of course, a great guide and mentor. with his plummy accent, country houses and when he grew up, Britten confidently The English composer Frank Bridge began royal connections, Benjamin Britten looked replied: ‘A composer.’ ‘But what else ?’ was the teaching composition to the teenage Britten every inch the English gentleman.