Jewish Communal Affairs

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Jewish Law and the Middle East Peace Process

Loyola of Los Angeles International and Comparative Law Review Volume 21 Number 2 Article 7 5-1-1999 Speech: Jewish Law and the Middle East Peace Process Abraham D. Sofaer Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lmu.edu/ilr Part of the Law Commons Recommended Citation Abraham D. Sofaer, Speech: Jewish Law and the Middle East Peace Process, 21 Loy. L.A. Int'l & Comp. L. Rev. 313 (1999). Available at: https://digitalcommons.lmu.edu/ilr/vol21/iss2/7 This Other is brought to you for free and open access by the Law Reviews at Digital Commons @ Loyola Marymount University and Loyola Law School. It has been accepted for inclusion in Loyola of Los Angeles International and Comparative Law Review by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons@Loyola Marymount University and Loyola Law School. For more information, please contact [email protected]. SPEECH Jewish Law and the Middle East Peace Process ABRAHAM D. SOFAER* Loyola Law School justifiably celebrates establishing the Sydney M. Irmas Memorial Chair in Jewish Law & Ethics. Loyola is determined, under Dean Gerald T. McLaughlin's leadership, to be a place where the law of Christianity, Islam, and Judaism is studied so that its students and the American legal system can derive and utilize the important lessons that these major religious law systems provide. This is a worthy objective, and one which friends of Loyola, and of the study of religious law, should warmly support. Dean McLaughlin asked me to speak on the Middle East peace process, in which I was privileged to play a part while serving as Legal Adviser to the Department of State. -

Jews Control U.S.A., Therefore the World – Is That a Good Thing?

Jews Control U.S.A., Therefore the World – Is That a Good Thing? By Chairman of the U.S. based Romanian National Vanguard©2007 www.ronatvan.com v. 1.6 1 INDEX 1. Are Jews satanic? 1.1 What The Talmud Rules About Christians 1.2 Foes Destroyed During the Purim Feast 1.3 The Shocking "Kol Nidre" Oath 1.4 The Bar Mitzvah - A Pledge to The Jewish Race 1.5 Jewish Genocide over Armenian People 1.6 The Satanic Bible 1.7 Other Examples 2. Are Jews the “Chosen People” or the real “Israel”? 2.1 Who are the “Chosen People”? 2.2 God & Jesus quotes about race mixing and globalization 3. Are they “eternally persecuted people”? 3.1 Crypto-Judaism 4. Is Judeo-Christianity a healthy “alliance”? 4.1 The “Jesus was a Jew” Hoax 4.2 The "Judeo - Christian" Hoax 4.3 Judaism's Secret Book - The Talmud 5. Are Christian sects Jewish creations? Are they affecting Christianity? 5.1 Biblical Quotes about the sects , the Jews and about the results of them working together. 6. “Anti-Semitism” shield & weapon is making Jews, Gods! 7. Is the “Holocaust” a dirty Jewish LIE? 7.1 The Famous 66 Questions & Answers about the Holocaust 8. Jews control “Anti-Hate”, “Human Rights” & Degraded organizations??? 8.1 Just a small part of the full list: CULTURAL/ETHNIC 8.2 "HATE", GENOCIDE, ETC. 8.3 POLITICS 8.4 WOMEN/FAMILY/SEX/GENDER ISSUES 8.5 LAW, RIGHTS GROUPS 8.6 UNIONS, OCCUPATION ORGANIZATIONS, ACADEMIA, ETC. 2 8.7 IMMIGRATION 9. Money Collecting, Israel Aids, Kosher Tax and other Money Related Methods 9.1 Forced payment 9.2 Israel “Aids” 9.3 Kosher Taxes 9.4 Other ways for Jews to make money 10. -

Holocaust) Victims Was Carried out in Israel

Loyola of Los Angeles International and Comparative Law Review Volume 41 Number 3 Article 19 Winter 2018 How Restitution of Property of Shoah (Holocaust) Victims was Carried Out in Israel Aharon Mor Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lmu.edu/ilr Recommended Citation Aharon Mor, How Restitution of Property of Shoah (Holocaust) Victims was Carried Out in Israel, 41 Loy. L.A. Int'l & Comp. L. Rev. 617 (2019). Available at: https://digitalcommons.lmu.edu/ilr/vol41/iss3/19 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Law Reviews at Digital Commons @ Loyola Marymount University and Loyola Law School. It has been accepted for inclusion in Loyola of Los Angeles International and Comparative Law Review by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons@Loyola Marymount University and Loyola Law School. For more information, please contact [email protected]. FINAL TO JCI (DO NOT DELETE) 12/12/2018 6:32 PM Holocaust Restitution: Israel Model How Restitution of Property of Shoah (Holocaust) Victims was Carried Out in Israel DR. AHARON (ARON) MOR 70 years after the Holocaust, the Company for Location and Restitution of Shoah Victims’ Assets was established, with the aim of doing historical justice with victims by returning their assets to their lawful heirs, and at the same time use assets whose owners were not located for assistance to Shoah needy survivors and perpetuating the memory of the Shoah. 1 Israel Peleg A unique effort to restore the property of Holocaust (Shoah) 2 victims in Israel began in 2007 and ended in December 2017.3 This unique process resulted in the restitution of assets of Israeli new shekel (“NIS”) 718 million (US $ 190.2 million)4 to 2,811 legal heirs, and NIS Israeli activist, researcher and lecturer on restitution of Jewish property from the Holocaust (Shoah) era and from Arab countries. -

Negevnow Negevnow

1 NEGEVNOW PRESIDENT’S REPORT 2014 NEGEVNOW BGU BELIEVES THAT DEVELOPING THE NEGEV WILL DO MORE THAN JUST BENEFIT THE REGION. IT WILL STRENGTHEN ISRAEL AS A WHOLE AND BE A “LIGHT UNTO THE NATIONS.” RANKED AS ONE OF THE WORLD’S TOP UNIVERSITIES UNDER 50 YEARS OLD, BGU ASPIRES TO BE A LEADING RESEARCH INSTITUTION THAT IMPACTS PEOPLE’S LIVES – THROUGH ACCESSIBLE EDUCATION, GROUND-BREAKING RESEARCH AND AN EMPHASIS ON SOCIAL JUSTICE. IN 2013, THE UNIVERSITY DOUBLED ITS PHYSICAL SIZE WITH THE ADDITION OF THE NEW NORTH CAMPUS. WITH THE OPENING OF THE ADVANCED TECHNOLOGIES PARK AND THE MOVE OF THE ISRAEL DEFENSE FORCES TO THE SOUTH, INTERNATIONAL COMPANIES AND GOVERNMENT AGENCIES ARE LEVERAGING THE PROXIMITY TO BGU TO OPEN RESEARCH FACILITIES IN THE REGION. BGU IS REALIZING ITS MISSION, IMPROVING PEOPLE'S LIVES IN ISRAEL AND AROUND THE WORLD. THE NEGEV IS NOW NORTHERN NEGEV RAMOT NEIGHBORHOOD BEER-SHEVA ILLUSTRATION OF THE FUTURE NORTH CAMPUS MARCUS FAMILY CAMPUS TRAIN LINE NEGEVNOW PRESIDENT’S REPORT 2014 ILLUSTRATION OF FUTURE CONFERENCE CENTER ON THE NORTH CAMPUS From the Chairman 8 From the President 9 BGU by the Numbers 10 Senior Administration 14 Campus Construction 16 The Spark of Innovation 18 A Game-Changing Approach 20 A History of Change 22 Breaking the Glass Ceiling 24 International Academic Affairs 26 New and Noteworthy 29 Community Outreach 39 Student Life 44 Recognizing our Friends 49 Board of Governors 77 Associates Organizations 80 ALUMNINOW BGU ALUMNI CARE. THEY GET INVOLVED. THEY PURSUE THEIR PASSIONS. THEY WORK TO IMPROVE THEIR WORLD. WE SALUTE OUR ALUMNI WHO ARE MAKING A DIFFERENCE. -

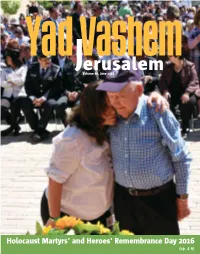

Jerusalemhem Volume 80, June 2016

Yad VaJerusalemhem Volume 80, June 2016 Holocaust Martyrs' and Heroes' Remembrance Day 2016 (pp. 4-9) Yad VaJerusalemhem Contents Volume 80, Sivan 5776, June 2016 Inauguration of the Moshe Mirilashvili Center for Research on the Holocaust in the Soviet Union ■ 2-3 Published by: Highlights of Holocaust Remembrance Day 2016 ■ 4-5 Students Mark Holocaust Remembrance Day Through Song, Film and Creativity ■ 6-7 Leah Goldstein ■ Remembrance Day Programs for Israel’s Chairman of the Council: Rabbi Israel Meir Lau Security Forces ■ 7 Vice Chairmen of the Council: ■ On 9 May 2016, Yad Vashem inaugurated Dr. Yitzhak Arad Torchlighters 2016 ■ 8-9 Dr. Moshe Kantor the Moshe Mirilashvili Center for Research on ■ 9 Prof. Elie Wiesel “Whoever Saves One Life…” the Holocaust in the Soviet Union, under the Chairman of the Directorate: Avner Shalev Education ■ 10-13 auspices of its world-renowned International Director General: Dorit Novak Asper International Holocaust Institute for Holocaust Research. Head of the International Institute for Holocaust Studies Program Forges Ahead ■ 10-11 The Center was endowed by Michael and Research and Incumbent, John Najmann Chair Laura Mirilashvili in memory of Michael’s News from the Virtual School ■ 10 for Holocaust Studies: Prof. Dan Michman father Moshe z"l. Alongside Michael and Laura Chief Historian: Prof. Dina Porat Furthering Holocaust Education in Germany ■ 11 Miriliashvili and their family, honored guests Academic Advisor: Graduate Spotlight ■ 12 at the dedication ceremony included Yuli (Yoel) Prof. Yehuda Bauer Imogen Dalziel, UK Edelstein, Speaker of the Knesset; Zeev Elkin, Members of the Yad Vashem Directorate: Minister of Immigration and Absorption and Yossi Ahimeir, Daniel Atar, Michal Cohen, “Beyond the Seen” ■ 12 Matityahu Drobles, Abraham Duvdevani, New Multilingual Poster Kit Minister of Jerusalem Affairs and Heritage; Avner Prof. -

Jerusalemhem QUARTERLY MAGAZINE, VOL

Yad VaJerusalemhem QUARTERLY MAGAZINE, VOL. 53, APRIL 2009 New Exhibit: The Republic of Dreams Bruno Schulz: Wall Painting Under Coercion (p. 4) ChildrenThe Central Theme forin Holocaust the RemembranceHolocaust Day 2009 (pp. 2-3) Yad VaJerusalemhem QUARTERLY MAGAZINE, VOL. 53, Nisan 5769, April 2009 Published by: Yad Vashem The Holocaust Martyrs’ and Heroes’ Remembrance Authority Children in the Holocaust ■ Chairman of the Council: Rabbi Israel Meir Lau Vice Chairmen of the Council: Dr. Yitzhak Arad Contents Dr. Israel Singer Children in the Holocaust ■ 2-3 Professor Elie Wiesel ■ On Holocaust Remembrance Day this year, The Central Theme for Holocaust Martyrs’ Chairman of the Directorate: Avner Shalev during the annual “Unto Every Person There and Heroes’ Remembrance Day 2009 Director General: Nathan Eitan is a Name” ceremony, we will read aloud the Head of the International Institute for Holocaust New Exhibit: names of children murdered in the Holocaust. Research: Professor David Bankier The Republic of Dreams ■ 4 Some faded photographs of a scattered few Chief Historian: Professor Dan Michman Bruno Schulz: Wall Painting Under Coercion remain, and their questioning, accusing eyes Academic Advisors: cry out on behalf of the 1.5 million children Taking Charge ■ 5 Professor Yehuda Bauer prevented from growing up and fulfilling their Professor Israel Gutman Courageous Nursemaids in a Time of Horror basic rights: to live, dream, love, play and Members of the Yad Vashem Directorate: Education ■ 6-7 laugh. Shlomit Amichai, Edna Ben-Horin, New International Seminars Wing Chaim Chesler, Matityahu Drobles, From the day the Nazis came to power, ,Abraham Duvdevani, ֿֿMoshe Ha-Elion, Cornerstone Laid at Yad Vashem Jewish children became acquainted with cruelty Yehiel Leket, Tzipi Livni, Adv. -

List of the Archives of Organizations and Bodies Held at the Central

1 Guide to the Archival Record Groups and Collections Notation Record group / Collection Dates Scanning Quantity 1. Central Offices of the World Zionist Organization and of the Jewish Agency for Palestine/Israel abroad Z1 Central Zionist Office, Vienna 1897-1905 scanned 13.6 Z2 Central Zionist Office, Cologne 1905-1911 scanned 11.8 not Z3 Central Zionist Office, Berlin 1911-1920 31 scanned The Zionist Organization/The Jewish Agency for partially Z4 1917-1955 215.2 Palestine/Israel - Central Office, London scanned The Jewish Agency for Palestine/Israel - American Section 1939 not Z5 (including Palestine Office and Zionist Emergency 137.2 onwards scanned Council), New York Nahum Goldmann's offices in New York and Geneva. See Z6 1936-1982 scanned 33.2 also Office of Nahum Goldmann, S80 not Z7 Mordecai Kirshenbloom's Office 1957-1968 7.8 scanned 2. Departments of the Executive of the World Zionist Organization and the Jewish Agency for Palestine/Israel in Jerusalem, Tel Aviv and Haifa not S1 Treasury Department 1918-1978 147.7 scanned not S33 Treasury Department, Budget Section 1947-1965 12.5 scanned not S105 Treasury Department, Section for Financial Information 1930-1959 12.8 scanned partially S6 Immigration Department 1919-1980 167.5 scanned S3 Immigration Department, Immigration Office, Haifa 1921-1949 scanned 10.6 S4 Immigration Department, Immigration Office, Tel Aviv 1920-1948 scanned 21.5 not S120 Absorption Department, Section for Yemenite Immigrants 1950-1957 1.7 scanned S84 Absorption Department, Jerusalem Regional Section 1948-1960 scanned 8.3 2 Guide to the Archival Record Groups and Collections not S112 Absorption Department, Housing Division 1951-1967 4 scanned not S9 Department of Labour 1921-1948 25.7 scanned Department of Labour, Section for the Supervision of not S10 1935-1947 3.5 Labour Exchanges scanned Agricultural Settlement Department. -

Israeli-German Relations in the Years 2000-2006: a Special Relationship Revisited

Israeli-German Relations in the Years 2000-2006: A Special Relationship Revisited Helene Bartos St. Antony’s College Trinity Term 2007 Thesis submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Philosophy in Modern Middle Eastern Studies Faculty of Oriental Studies University of Oxford To my mother and Joe Acknowledgements I would like to use the opportunity to express my deepest gratitude to my supervisor Dr. Emanuele Ottolenghi, who generously agreed to oversee my thesis from afar having taken up his post as the Executive Director of the Transatlantic Institute in Brussels in September 2006. Without his full-hearted support and his enduring commitment my research would not have materialised. I am further deeply indebted to Dr. Michael Willis who dedicated his precious time to discuss with me issues pertaining to my research. Special thanks also goes to Dr. Philip Robins, Senior Tutor at St. Antony’s College, for having supported my field work in Germany in the summer vacation of 2006 with a grant from the Carr and Stahl Funds, and to the Hebrew and Jewish Studies Committee and Near and Middle Eastern Studies Committee for having awarded me two research grants to finance my field work in Israel in the winter of 2006. Without listing everyone personally, I would like to thank all my interview partners as well as colleagues and friends who shared with me their thoughts on the nature of the Israeli-German relationship. Having said all this, it is only due to my mother and my boyfriend Joe who have supported me throughout six not always easy years that I have been able to study at Oxford. -

Guide to the Archival Record Groups and Collections

GUIDE TO THE ARCHIVAL RECORD GROUPS AND COLLECTIONS Jerusalem, July 2003 The contents of this Guide, and other information on the Central Zionist Archives, may be found on Internet at the following address: http://www.zionistarchives.org.il/ The e-mail address of the Archives is: [email protected] 2 Introduction This edition of the Guide to the Archival Record Groups and Collections held at the Central Zionist Archives has once again been expanded. It includes new acquisitions of material, which have been received recently at the CZA. In addition, a new section has been added, the Maps and Plans Section. Some of the collections that make up this section did appear in the previous Guide, but did not make up a separate section. The decision to collect the various collections in one section reflects the large amount of maps and plans that have been acquired in the last two years and the advancements made in this sphere at the CZA. Similarly, general information about two additional collections has been added in the Guide, the Collection of Announcements and the Collection of Badges. Explanation of the symbols, abbreviations and the structure of the Guide: Dates appearing alongside the record groups names, signify: - with regard to institutional archives: the period in which the material that is stored in the CZA was created. - with regard to personal archives: the birth and death dates of the person. Dates have not been given for living people. The numbers in the right-hand margin signify the amount of material comprising the record group, in running meters of shelf space (one running meter includes six boxes of archival material). -

President's Report 2018

VISION COUNTING UP TO 50 President's Report 2018 Chairman’s Message 4 President’s Message 5 Senior Administration 6 BGU by the Numbers 8 Building BGU 14 Innovation for the Startup Nation 16 New & Noteworthy 20 From BGU to the World 40 President's Report Alumni Community 42 2018 Campus Life 46 Community Outreach 52 Recognizing Our Friends 57 Honorary Degrees 88 Board of Governors 93 Associates Organizations 96 BGU Nation Celebrate BGU’s role in the Israeli miracle Nurturing the Negev 12 Forging the Hi-Tech Nation 18 A Passion for Research 24 Harnessing the Desert 30 Defending the Nation 36 The Beer-Sheva Spirit 44 Cultivating Israeli Society 50 Produced by the Department of Publications and Media Relations Osnat Eitan, Director In coordination with the Department of Donor and Associates Affairs Jill Ben-Dor, Director Editor Elana Chipman Editorial Staff Ehud Zion Waldoks, Jacqueline Watson-Alloun, Angie Zamir Production Noa Fisherman Photos Dani Machlis Concept and Design www.Image2u.co.il 4 President's Report 2018 Ben-Gurion University of the Negev - BGU Nation 5 From the From the Chairman President Israel’s first Prime Minister, David Ben–Gurion, said:“Only Apartments Program, it is worth noting that there are 73 This year we are celebrating Israel’s 70th anniversary and Program has been studied and reproduced around through a united effort by the State … by a people ready “Open Apartments” in Beer-Sheva’s neighborhoods, where acknowledging our contributions to the State of Israel, the the world and our students are an inspiration to their for a great voluntary effort, by a youth bold in spirit and students live and actively engage with the local community Negev, and the world, even as we count up to our own neighbors, encouraging them and helping them strive for a inspired by creative heroism, by scientists liberated from the through various cultural and educational activities. -

Jewish Education (CIJE)

THE JACOB RADER MARCUS CENTER OF THE AMERICAN JEWISH ARCHIVES MS-831: Jack, Joseph and Morton Mandel Foundation Records, 1980–2008. Series C: Council for Initiatives in Jewish Education (CIJE). 1988–2003. Subseries 5: Communication, Publications, and Research Papers, 1991–2003. Box Folder 46 7 Press clippings, 1995-1996. For more information on this collection, please see the finding aid on the American Jewish Archives website. 3101 Clifton Ave, Cincinnati, Ohio 45220 513.487.3000 AmericanJewishArchives.org UA5HINGTO H JEUISH UEEK WASHINGTON, DC WEEKLY 21, GOO JAN 5 1995 13 HR .l<C'i! . 'l , r ( Keep a high wall of separation why federations support day Republican majorities m the £310 schools. House and Senate but also a by Yosef I. Abramowitz In November at the Gen dangerous streak of selfish Spec13I to WJW eral Assemply of the Cotl6cil ness into the mainstream of of Jewish Federations, phi society's deliberations. Under here is a small religious lanthropist Edgar Bronfman presidents Reagan and Bush group in Florid-0 that called for universal Jewish it would have been u naccept~ Tsacr ifices antmals. a day school education regard able to talk about orphanages practice Jews gave up nearly less of cost. Many federations and cuttmg off food money 2,000 years ago. Yet if some are looking for ways to raise for poor children who were federation leaders had their more money to support this born out of wedlock. way, the Jewish community vital aspect of the conunuity But now we are witnessing would advocate that the gov agenda. the abandonment of even the ernment should subsidize the most vulnerable members of religious education of the our society, all in the name sect's children. -

March 2020.Pub

The Bulletin Congregation Shaaray Shalom .&-: *93: %-*%8 Jewish Community Center of West Hempstead Franklin Square Jewish Center Conservative Egalitarian Synagogue 711 Dogwood Avenue, West Hempstead, NY 11552-3425 516 481-7448 Fax: 516 489-9573 www.shaarayshalom.org Rabbi Art Vernon March 2020 Adar/Nisan 5780 Cantor civilizations permitted us. Todd Rosner Rabbi’s Message But, unless the king's laws violated our religious principles, we observed the President While most of us enjoy the Alan Shamoun laws of the land of our host countries. In celebratory aspects of Purim, there is a fact, we made observing the local laws a st serious theme of the holiday. Haman is the 1 Vice President religious principle of Judaism - dinah Leah Freeberg villain of the story because he tried to d'malchuta dinah - the law of the kingdom is exterminate the entire Jewish people of nd the law. 2 Vice President Persia, in a sense, the first holocaust in Daniel Alter Nevertheless, we were a minority in Jewish history. The canard he raised against every country of the world in which we the Jews of Persia became the template for Treasurer lived. Our rights and privileges were Lew Stein anti-Semitism throughout the ages. He determined by the host country and our accused the Jewish people of being status varied from place to place over Financial Secretary dispersed among the people of the land, Ronni Pollack time. At times we were warmly welcomed observing their own laws and not following and flourished and, sadly, at times we were the king's laws.