Barber Adagio for Strings

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Barber Piano Sonata in E-Flat Minor, Opus 26

Barber Piano Sonata In E-flat Minor, Opus 26 Comparative Survey: 29 performances evaluated, September 2014 Samuel Barber (1910 - 1981) is most famous for his Adagio for Strings which achieved iconic status when it was played at F.D.R’s funeral procession and at subsequent solemn occasions of state. But he also wrote many wonderful songs, a symphony, a dramatic Sonata for Cello and Piano, and much more. He also contributed one of the most important 20th Century works written for the piano: The Piano Sonata, Op. 26. Written between 1947 and 1949, Barber’s Sonata vies, in terms of popularity, with Copland’s Piano Variations as one of the most frequently programmed and recorded works by an American composer. Despite snide remarks from Barber’s terminally insular academic contemporaries, the Sonata has been well received by audiences ever since its first flamboyant premier by Vladimir Horowitz. Barber’s unique brand of mid-20th Century post-romantic modernism is in full creative flower here with four well-contrasted movements that offer a full range of textures and techniques. Each of the strongly characterized movements offers a corresponding range of moods from jagged defiance, wistful nostalgia and dark despondency, to self-generating optimism, all of which is generously wrapped with Barber’s own soaring lyricism. The first movement, Allegro energico, is tough and angular, the most ‘modern’ of the movements in terms of aggressive dissonance. Yet it is not unremittingly pugilistic, for Barber provides the listener with alternating sections of dreamy introspection and moments of expansive optimism. The opening theme is stern and severe with jagged and dotted rhythms that give a sense of propelling physicality of gesture and a mood of angry defiance. -

Music of Samuel Barber

July 24, 2016 :: Las Puertas :: Albuquerque :: #418 Music of Samuel Barber (1910–1981) 6-year-old Moxie is attending her A performance to share the music of Samuel Barber, composer of the opera very first Chatter concert. Vanessa, performed for the first time this summer at The Santa Fe Opera. G-Ma and Poppa love Moxie. Rebecca Krynski Cox soprano | Jarrett Ott baritone Robert Tweten piano Del Sol String Quartet featuring Benjamin Kreith, Rick Shinozaki violin Charlton Lee viola | Kathryn Bates cello CHATTER SUNDAY Three Songs Opus 10 (1936) Sunday, July 31 @ 10:30am III I Hear an Army Peter Gilbert Intermezzi, world premiere Love at the Door (1934) Philip Glass Etudes No. 3, 2, 8, and 9 Four Songs Opus 13 (1940) III Sure on this Shining Night Aaron Jay Kernis Air for Violin and Piano Frederic Rzewski ABQ Slam Team poets Winnsboro Cotton Mill Blues Emanuele Arciuli piano Dover Beach Opus 3 (1931) David Felberg violin String Quartet Opus 11 (1936) Rich Boucher poet I Molto allegro e appassionata II Molto adagio (attacca) CHATTER SUNDAY III Molto allegro (come prima) 50 weeks every year at 10:30am Las Puertas, 1512 1st St NW, Abq Celebration of Silence :: Two Minutes Subscribe to eNEWS at ChatterABQ.org Videos at YouTube.com/ChatterABQ Share/follow us on social media: Hermit Songs Opus 29 (1953) · facebook.com/ChatterABQ I At Saint Patrick’s Purgatory VI Sea-Snatch · twitter.com/ChatterABQ II Church Bells at Night VII Promiscuity · instagram.com/ChatterABQ III St. Ita’s Vision VIII The Monk and His Cat Tix at ChatterABQ.org/boxoffice IV The Heavenly Banquet IX The Praises of God V The Crucifixion X The Desire of Hermitage Chatter is grateful for the support of the National Endowment for the Arts About Vanessa by Samuel Barber :: A Company Premiere Sung in English with Opera Titles in English and Spanish. -

The Critical Reception of Beethoven's Compositions by His German Contemporaries, Op. 123 to Op

The Critical Reception of Beethoven’s Compositions by His German Contemporaries, Op. 123 to Op. 124 Translated and edited by Robin Wallace © 2020 by Robin Wallace All rights reserved. ISBN 978-1-7348948-4-4 Center for Beethoven Research Boston University Contents Foreword 6 Op. 123. Missa Solemnis in D Major 123.1 I. P. S. 8 “Various.” Berliner allgemeine musikalische Zeitung 1 (21 January 1824): 34. 123.2 Friedrich August Kanne. 9 “Beethoven’s Most Recent Compositions.” Allgemeine musikalische Zeitung mit besonderer Rücksicht auf den österreichischen Kaiserstaat 8 (12 May 1824): 120. 123.3 *—*. 11 “Musical Performance.” Wiener Zeitschrift für Kunst, Literatur, Theater und Mode 9 (15 May 1824): 506–7. 123.4 Ignaz Xaver Seyfried. 14 “State of Music and Musical Life in Vienna.” Caecilia 1 (June 1824): 200. 123.5 “News. Vienna. Musical Diary of the Month of May.” 15 Allgemeine musikalische Zeitung 26 (1 July 1824): col. 437–42. 3 contents 123.6 “Glances at the Most Recent Appearances in Musical Literature.” 19 Caecilia 1 (October 1824): 372. 123.7 Gottfried Weber. 20 “Invitation to Subscribe.” Caecilia 2 (Intelligence Report no. 7) (April 1825): 43. 123.8 “News. Vienna. Musical Diary of the Month of March.” 22 Allgemeine musikalische Zeitung 29 (25 April 1827): col. 284. 123.9 “ .” 23 Allgemeiner musikalischer Anzeiger 1 (May 1827): 372–74. 123.10 “Various. The Eleventh Lower Rhine Music Festival at Elberfeld.” 25 Allgemeine Zeitung, no. 156 (7 June 1827). 123.11 Rheinischer Merkur no. 46 27 (9 June 1827). 123.12 Georg Christian Grossheim and Joseph Fröhlich. 28 “Two Reviews.” Caecilia 9 (1828): 22–45. -

A Formal Analytical Approach Was Utilized to Develop Chart Analyses Of

^ DOCUMENT RESUME ED 026 970 24 HE 000 764 .By-Hanson, John R. Form in Selected Twentieth-Century Piano Concertos. Final Report. Carroll Coll., Waukesha, Wis. Spons Agency-Office of Education (DHEW), Washington, D.C. Bureauof Research. Bureau No-BR-7-E-157 Pub Date Nov 68 Crant OEC -0 -8 -000157-1803(010) Note-60p. EDRS Price tvw-s,ctso HC-$3.10 Descriptors-Charts, Educational Facilities, *Higher Education, *Music,*Music Techniques, Research A formal analytical approach was utilized to developchart analyses of all movements within 33 selected piano concertoscomposed in the twentieth century. The macroform, or overall structure, of each movement wasdetermined by the initial statement, frequency of use, andorder of each main thematic elementidentified. Theme groupings were then classified underformal classical prototypes of the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries (ternary,sonata-allegro, 5-part or 7-part rondo, theme and variations, and others), modified versionsof these forms (three-part design), or a variety of free sectionalforms. The chart and thematic illustrations are followed by a commentary discussing each movement aswell as the entire concerto. No correlation exists between styles andforms of the 33 concertos--the 26 composers usetraditional,individualistic,classical,and dissonant formsina combination of ways. Almost all works contain commonunifying thematic elements, and cyclicism (identical theme occurring in more than1 movement) is used to a great degree. None of the movements in sonata-allegroform contain double expositions, but 22 concertos have 3 movements, and21 have cadenzas, suggesting that the composers havelargely respected standards established in theClassical-Romantic period. Appendix A is the complete form diagramof Samuel Barber's Piano Concerto, Appendix B has concentrated analyses of all the concertos,and Appendix C lists each movement accordog to its design.(WM) DE:802 FINAL REPORT Project No. -

Bach, Barber, and Brahms: Masters of Emotive Violin Composition Edward Charity Southern Illinois University Carbondale, [email protected]

Southern Illinois University Carbondale OpenSIUC Research Papers Graduate School Summer 6-30-2014 Bach, Barber, and Brahms: Masters of Emotive Violin Composition Edward Charity Southern Illinois University Carbondale, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://opensiuc.lib.siu.edu/gs_rp Recommended Citation Charity, Edward, "Bach, Barber, and Brahms: Masters of Emotive Violin Composition" (2014). Research Papers. Paper 551. http://opensiuc.lib.siu.edu/gs_rp/551 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at OpenSIUC. It has been accepted for inclusion in Research Papers by an authorized administrator of OpenSIUC. For more information, please contact [email protected]. BACH, BARBER, AND BRAHMS: MASTERS OF EMOTIVE VIOLIN COMPOSITION by Edward Charity B.M., Northwestern State University, 2011. A Research Paper Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Master of Music Department of Music in the Graduate School Southern Illinois University Carbondale August 2014 RESEARCH PAPER APPROVAL BACH, BARBER, AND BRAHMS: MASTERS OF EMOTIVE VIOLIN COMPOSITION By Edward Charity A Research Paper Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Music in the field of Music Performance Approved by: Michael Barta, Chair Eric Lenz Jacob Tews Graduate School Southern Illinois University Carbondale June 28, 2014 AN ABSTRACT OF THE RESEARCH PAPER OF Edward Charity, for the Master of Music degree in Music Performance, presented on June 30, 2014, at Southern Illinois University Carbondale. TITLE: BACH, BARBER, AND BRAHMS: MASTERS OF EMOTIVE VIOLIN COMPOSITION MAJOR PROFESSOR: Michael Barta Three seminal works of the violin repertory will be examined: J.S. -

VANESSA Composer: Samuel Barber Libretto by Gian Carlo Menotti After a Story by Isak Dinesen in Seven Gothic Tales

VANESSA Composer: Samuel Barber Libretto by Gian Carlo Menotti after a story by Isak Dinesen in Seven Gothic Tales Vanessa has spent twenty years in her country house after being left by her lover, Anatol; she has kept the house shut up, with all of the mirrors covered. Her mother, the Old Baroness, will not speak to her; her only companion is her niece, Erika. As the opera opens, they are preparing for the arrival of Anatol. He is sighted coming towards the house, and Vanessa sends everyone else away; as soon as he arrives at the door, she declares her love for him--then faints when she discovers that the man on the doorstep is not her lover. He is, he explains to Erika, that Anatol's son; he has come to meet the woman whose name haunted his father and mother. The Anatol that Vanessa knew has died. Anatol, left alone with Erika, seduces her; the next day, after Erika learns that he has been making advances to Vanessa, she confronts him; he offers to marry her, but, offended by the flippancy with which he has proposed, and worried about Vanessa, rejects him. At the party where Vanessa and Anatol's engagement is announced, Erika reveals to the Old Baroness that she is pregnant with Anatol's child. She runs away from the house and causes herself to miscarry; a search party sent out by Vanessa brings her back. Vanessa, still unaware of Anatol's liason with Erika, marries him, and they leave together. Erika, left alone in the house with her grandmother, who now will not speak to her, orders the mirrors covered again and the gates closed and locked, just as before. -

Boston Symphony Orchestra Concert Programs, Summer, 1963-1964

TANGLEWOOD Festival of Contemporary American Music August 9, 10, 11, 12, 13, 1964 Sponsored by the Berkshire Music Center In Cooperation with the Fromm Music Foundation RCA Victor R£D SEAL festival of Contemporary American Composers DELLO JOIO: Fantasy and Variations/Ravel: Concerto in G Hollander/Boston Symphony Orchestra/Leinsdorf LM/LSC-2667 COPLAND: El Salon Mexico Grofe-. Grand Canyon Suite Boston Pops/ Fiedler LM-1928 COPLAND: Appalachian Spring The Tender Land Boston Symphony Orchestra/ Copland LM/LSC-240i HOVHANESS: BARBER: Mysterious Mountain Vanessa (Complete Opera) Stravinsky: Le Baiser de la Fee (Divertimento) Steber, Gedda, Elias, Mitropoulos, Chicago Symphony/Reiner Met. Opera Orch. and Chorus LM/LSC-2251 LM/LSC-6i38 FOSS: IMPROVISATION CHAMBER ENSEMBLE Studies in Improvisation Includes: Fantasy & Fugue Music for Clarinet, Percussion and Piano Variations on a Theme in Unison Quintet Encore I, II, III LM/LSC-2558 RCA Victor § © The most trusted name in sound BERKSHIRE MUSIC CENTER ERICH Leinsdorf, Director Aaron Copland, Chairman of the Faculty Richard Burgin, Associate Chairman of the Faculty Harry J. Kraut, Administrator FESTIVAL of CONTEMPORARY AMERICAN MUSIC presented in cooperation with THE FROMM MUSIC FOUNDATION Paul Fromm, President Alexander Schneider, Associate Director DEPARTMENT OF COMPOSITION Aaron Copland, Head Gunther Schuller, Acting Head Arthur Berger and Lukas Foss, Guest Teachers Paul Jacobs, Fromm Instructor in Contemporary Music Stanley Silverman and David Walker, Administrative Assistants The Berkshire Music Center is the center for advanced study in music sponsored by the BOSTON SYMPHONY ORCHESTRA Erich Leinsdorf, Music Director Thomas D. Perry, Jr., Manager BALDWIN PIANO RCA VICTOR RECORDS — 1 PERSPECTIVES OF NEW MUSIC Participants in this year's Festival are invited to subscribe to the American journal devoted to im- portant issues of contemporary music. -

Beethoven (1819-1823) (1770-1827)

Friday, May 10, 2019, at 8:00 PM Saturday, May 11, 2019, at 3:00 PM MISSA SOLEMNIS IN D, OP. 123 Ludwig van Beethoven (1819-1823) (1770-1827) Tami Petty, soprano Helen KarLoski, mezzo-soprano Dann CoakwelL, tenor Joseph Beutel, bass-baritone Kyrie GLoria Credo Sanctus and Benedictus* Agnus Dei * Jorge ÀviLa, violin solo Approximately 80 minutes, performed without intermission. PROGRAM NOTES The biographer Maynard SoLomon him to conceptuaLize the Missa as a work described the Life of Ludwig van of greater permanence and universaLity, a Beethoven (1770-1827) as “a series of keystone of his own musicaL and creative events unique in the history of personaL Legacy. mankind.” Foremost among these creative events is the Missa Solemnis The Kyrie and GLoria settings were (Op. 123), a work so intense, heartfeLt and largely complete by March of 1820, with originaL that it nearly defies the Credo, Sanctus, Benedictus and categorization. Agnus Dei foLLowing in Late 1820 and 1821. Beethoven continued to poLish the work Beethoven began the Missa in 1819 in through 1823, in the meantime response to a commission from embarking on a convoLuted campaign to Archduke RudoLf of Austria, youngest pubLish the work through a number of son of the Hapsburg emperor and a pupiL competing European houses. (At one and patron of the composer. The young point, he represented the existence of no aristocrat desired a new Mass setting for less than three Masses to various his enthronement as Archbishop of pubLishers when aLL were one and the Olmütz (modern day Olomouc, in the same.) A torrent of masterworks joined Czech RepubLic), scheduLed for Late the the Missa during this finaL decade of following year. -

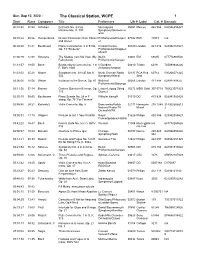

The Classical Station, WCPE 1 Start Runs Composer Title Performerslib # Label Cat

Sun, Sep 13, 2020 - The Classical Station, WCPE 1 Start Runs Composer Title PerformersLIb # Label Cat. # Barcode 00:01:30 07:52 Schubert Entr'acte No. 3 from Minneapolis 05051 Mercury 462 954 028946295427 Rosamunde, D. 797 Symphony/Skrowacze wski 00:10:2208:46 Humperdinck Dream Pantomime from Hansel Philharmonia/Klemper 07382 EMI 13073 n/a and Gretel er 00:20:0838:41 Beethoven Piano Concerto No. 5 in E flat, Curzon/Vienna 04349 London 421 616 028942161627 Op. 73 "Emperor" Philharmonic/Knappert sbusch 01:00:19 12:38 Smetana The Moldau from Ma Vlast (My Berlin 03600 EMI 69005 077776900520 Fatherland) Philharmonic/Karajan 01:13:5718:05 Bach Brandenburg Concerto No. 1 in Il Giardino 04810 Teldec 6019 745099844226 F, BWV 1046 Armonico/Antonini 01:33:02 25:28 Mozart Symphony No. 39 in E flat, K. North German Radio 02135 RCA Red 60714 090266071425 543 Symphony/Wand Seal 02:00:0010:56 Weber Invitation to the Dance, Op. 65 National 00266 London 411 898 02894189820 Philharmonic/Bonynge 02:11:56 37:14 Brahms Clarinet Quintet in B minor, Op. Leister/Leipzig String 10273 MDG Gold 307 0719 760623071923 115 Quartet 02:50:1008:00 Beethoven Piano Sonata No. 24 in F Wilhelm Kempff 01310 DG 415 834 028941583420 sharp, Op. 78 "For Therese" 02:59:40 29:21 Karlowicz Violin Concerto, Op. 8 Danczowka/Polish 02170 Harmonia 278 1088 314902505612 National Radio-TV Mundi 2 Orchestra/Wit 03:30:0111:19 Wagner Prelude to Act 1 from Parsifal Royal 01626 Philips 420 886 028942088627 Concertgebouw/Haitink 03:42:2016:47 Bach French Suite No. -

Barber–String Quartet

Samuel Barber (b. West Chester, PA, March 9, 1910; d. New York, NY, January 23, 1981) String Quartet, op. 11 (1936) Composed: 1936 Approximate duration: 16 minutes Since accompanying the radio announcement of President Franklin Roosevelt’s death in 1945, Samuel Barber’s Adagio for Strings has stood as arguably the most iconic work of American classical repertoire. As a compositional feat, the Adagio is nothing short of a minor miracle: melodically and harmonically concise, emotionally devastating. It epitomizes the fervent lyricism and expressive immediacy that have established Barber among the twentieth century’s most venerated American musical figures. While frequently performed in Barber’s version for string orchestra, the Adagio less often appears in its original form, as the second movement (marked Molto adagio) of his String Quartet, op. 11, composed in 1936. (Barber, nota bene, recognized what he had accomplished; on September 19 of that year, he wrote to the cellist Orlando Cole, “I have just finished the slow movement of my quartet today—it is a knockout! Now for a Finale.”) Yet its presentation in the context of the three-movement Quartet affords the listener a special opportunity. Played by just two violins, viola, and cello, the Adagio’s breathless lines burn with an intimate intensity muted by the quiet army of orchestral strings. Furthermore, framed by the Quartet’s outer movements—the angular Molto allegro e appassionato, and the concluding reprise of the first movement’s material—the ubiquitous slow movement takes on a more nuanced significance. For prefaced by the angular dissonance of the opening movement, the Adagio emerges as a response to worldly strife. -

Program Notes

with the NASHVILLESYMPHONY CLASSICAL SERIES THURSDAY, FEBRUARY 21, AT 7 PM | FRIDAY & SATURDAY, FEBRUARY 22 & 23, AT 8 PM NASHVILLE SYMPHONY GIANCARLO GUERRERO, conductor CONCERT PARTNER ALBAN GERHARDT, cello AARON JAY KERNIS Symphony No. 4, “Chromelodeon” Out of Silence Thorn, Rose | Weep, Freedom (after Handel) Fanfare Chromelodia SAMUEL BARBER This weekend's performances are made Concerto for Cello and Orchestra, Op. 22 possible through the generosity of Allegro moderato Drs. Mark & Nancy Peacock. Andante sostenuto Molto allegro ed appassionato Alban Gerhardt, cello – INTERMISSION – LUDWIG VAN BEETHOVEN Symphony No. 7 in A Major, Op. 92 Poco sostenuto – Vivace Allegretto Presto Allegro con brio This concert will last 1 hour and 55 miutes, including a 20-minute intermission. INCONCERT 33 TONIGHT’S CONCERT AT A GLANCE AARON JAY KERNIS Symphony No. 4, “Chromelodeon” • New York City-based composer Kernis has earned the Pulitzer Prize in Music and the prestigious Grawemeyer Award, as well a 2019 GRAMMY® nomination for Best Contemporary Classical Composition. (Winners had not yet been announced at the time of the program guide’s printing.) He also serves as workshop director for the Nashville Symphony’s Composer Lab & Workshop. • The title of his latest symphony, “Chromelodeon,” comes from an unusual word previously used by maverick American composer Harry Partch to describe one of his musical inventions. As defined by the composer, this word aptly describes his own creation here: “chromatic, colorful, melodic music performed by an orchestra.” • The idea of color is especially significant in Kernis’ work, as the composer has synesthesia, a condition that associates specific notes and chords and with distinct colors. -

Music of the Baroque Chorus and Orchestra War and Peace

Music of the Baroque Chorus and Orchestra War and Peace Jane Glover, Music Director Jane Glover, conductor William Jon Gray, chorus director Soprano Violin 1 Flute Laura Amend Robert Waters, Mary Stolper Sunday, May 17, 2015, 7:30 PM Alyssa Bennett concertmaster Pick-Staiger Concert Hall, Evanston Bethany Clearfield Kevin Case Oboe Sarah Gartshore* Teresa Fream Robert Morgan, principal Monday, May 18, 2015, 7:30 PM Katelyn Lee Kathleen Brauer Peggy Michel Harris Theater, Chicago (Millennium Park) Hannah Dixon Michael Shelton McConnell Ann Palen Clarinet Sarah Gartshore, soprano Susan Nelson Steve Cohen, principal Kathryn Leemhuis, mezzo-soprano Anne Slovin Violin 2 Daniel Won Ryan Belongie, countertenor Alison Wahl Sharon Polifrone, Zach Finkelstein, tenor Emily Yiannias principal Bassoon Roderick Williams, baritone Fox Fehling William Buchman, Alto Ronald Satkiewicz principal Te Deum for the Victory of Dettingen, HWV 283 George Frideric Handel Ryan Belongie* Rika Seko Lewis Kirk (1685–1759) Julie DeBoer Paul Vanderwerf 1. Chorus: We praise Thee, o God Julia Elise Hardin Horn 2. Soli (alto, tenor) and Chorus: All the earth doth worship Thee Amanda Koopman Viola Jon Boen, principal 3. Chorus: To Thee all angels cry aloud Kathryn Leemhuis* Elizabeth Hagen, Neil Kimel 4. Chorus: To Thee Cherubim and Seraphim Maggie Mascal principal 5. Chorus: The glorious company of the apostles Emily Price Terri Van Valkinburgh Trumpet 6. Aria (baritone) and Chorus: Thou art the King of Glory Claudia Lasareff-Mironoff Barbara Butler, 7. Aria (baritone): When Thou tookest upon Thee Tenor Benton Wedge co-principal 8. Chorus: When Thou hadst overcome Madison Bolt Charles Geyer, 9. Trio (alto, tenor, baritone): Thou sittest at the right hand of God Zach Finkelstein* Cello co-principal 10.