Letronne Intro.REVISED Paginated

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Nippur; Or, Explorations and Adventures on the Euphrates; The

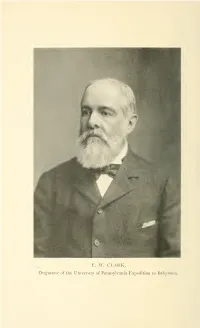

E. \V. CLARK. Originator of the University of Pennsylvania Expedition to Babylonia. NIPPUR OR EXPLORATIONS AND ADVENTURES ON THE EUPHRATES THE NARRATIVE OF THE UNIVERSITY OF PENNSYLVANIA EXPEDITION TO BABYLONIA IN THE YEARS 1888-1890 BY JOHN PUNNETT PETERS, PH.D., Sc.D., D.D. Director of the Expedition WITH ILLUSTRATIONS AND MAPS VOLUME 1. FIRST CAMPAIGN SECOND EDITION G. P. PUTNAM'S SONS NEW YORK AND LONDON i,\t llnickcrbocktt ^rcss i8q8 Copyright, 1897 BY G. P. PUTNAM'S SONS Entered at Stationers' Hall, London Ube Iktiicherbocfter iPress, IRew jgorft To THE Public-Spirited Gentlemen OF Philadelphia WHO MADE THE EXPEDITION POSSIBLE THESE Volumes are Respectfully Dedicated PREFACE. No city in this country has shown an interest in archeol- ogy at all comparable with that displayed by Philadelphia, A group of public-spirited gentlemen in that city has given without stint time and money for explorations in Babylonia, Egypt, Central America, Italy, Greece, and our own land ; and has, within the last ten years amassed archaeological col- lections which are unsurpassed in this country. The first im- portant work undertaken was the Babylonian Expedition. As described in the Narrative, this expedition was inaugurated by a Philadelphia banker, Mr. E. W. Clark. The enterprise was taken up in its infancy by the University of Pennsylvania, under the lead of its provost, Dr. William Pepper. Dr. Pepper made this expedition and the little band of men who liad become interested in it the nucleus for further enterprises. A library and museum were built, an Archaeological Associa- tion was formed, and a band of men was gathered together in Philadelphia who have contributed with a liberality and en- thusiasm quite unparalleled for the prosecution of archaeologi- cal research in almost all parts of the world. -

Outlines of the Evolution of Weights and Measures and the Metric System

OUTLINES OF THE EVOLUTION OF WEIGHTS AND MEASUEES AND THE METRIC SYSTEM OUTLINES OF THE EVOLUTION OF WEIGHTS AND MEASURES AND THE METRIC SYSTEM BY WILLIAM HALLOCK Ph.D. PROFESSOR OF PHYSIOS IN COLUMBIA UNIVERSITY IN THE CITY OF NEW YORK AND HERBERT T. WADE EDITOR FOR PHYSICS AND APPLIED SCIENCE, ' THK NEW INTERNATIONAL ENCYCLOPAEDIA THE MACMILLAN COMPANY LONDON : MACMILLAN AND CO. LTD. 1906 ac 2b SEP 8 <i ;\ OFT 9239G3 GLASGOW I PRINTED AT THE UNIVERSITY BY ROBERT MACLEHOSE AND CO. LTD. PREFACE. In the following pages it has been the aim of the authors to present in simple and non-technical language, so far as possible, a comprehensive view of the evolution of the science of metrology as it is now understood. Inasmuch as the introduction of the Metric System into the United States and Great Britain is a topic of more or less general interest at the present time, it has seemed that a work designed both for the student of science and for the general reader, in which this system is discussed in its relation to other systems of weights and measures past and present, would fill a certain need. While there are many works on metrology that treat at considerable length the historic and scientific sides of the subject, as well as the economic and archaeological questions involved, and a large number of books and pamphlets dealing with the teaching of the Metric System, besides those supplying tables and formulas for converting from one system to the other, yet there is apparently a distinct lack of works, which in small compass discuss the subject comprehensively from its many points of view. -

Encyclopaedia of Scientific Units, Weights and Measures Their SI Equivalences and Origins

FrancËois Cardarelli Encyclopaedia of Scientific Units, Weights and Measures Their SI Equivalences and Origins English translation by M.J. Shields, FIInfSc, MITI 13 Other Systems 3 of Units Despite the internationalization of SI units, and the fact that other units are actually forbidden by law in France and other countries, there are still some older or parallel systems remaining in use in several areas of science and technology. Before presenting conversion tables for them, it is important to put these systems into their initial context. A brief review of systems is given ranging from the ancient and obsolete (e.g. Egyptian, Greek, Roman, Old French) to the relatively modern and still in use (e.g. UK imperial, US customary, cgs, FPS), since a general knowledge of these systems can be useful in conversion calculations. Most of the ancient systems are now totally obsolete, and are included for general or historical interest. 3.1 MTS, MKpS, MKSA 3.1.1 The MKpS System The former system of units referred to by the international abbreviations MKpS, MKfS, or MKS (derived from the French titles meÁtre-kilogramme-poids-seconde or meÁtre-kilo- gramme-force-seconde) was in fact entitled SysteÁme des MeÂcaniciens (Mechanical Engi- neers' System). It was based on three fundamental units, the metre, the second, and a weight unit, the kilogram-force. This had the basic fault of being dependent on the acceleration due to gravity g, which varies on different parts of the Earth, so that the unit could not be given a general definition. Furthermore, because of the lack of a unit of mass, it was difficult, if not impossible to draw a distinction between weight, or force, and mass (see also 3.4). -

Ancient Anatolian Grids

Ancient Anatolian Grids Şirin Gülcen EREN Süleyman Demirel University, Faculty of Architecture Department of City and Regional Planning, [email protected] / [email protected] Abstract: For as long as humans have existed, they have created specific legal structures and technical means of representation in order to situate themselves within the geographical space where they live, to find the right direction, to measure time and distance, to define property and to calculate gradients. With the progress of civilisation, maps came to be used as an instrument for controlling society, siting architectural structures, establishing towns and determining trade axes and property rights. As social structures and the needs and relationships embedded in them changed, and technical and technological methods became more advanced, cartography developed too, and the uses of maps increased. From their earliest discovery, the basic characteristics of maps were grids, isohypses (contours) and physical data. The geography and settlements of Anatolia provide some clues as to the types of grid that were used in ancient times. There are invisible grids compatible with Euclidean geometry. These can only be detected from the clues given by the settlement locations. These grids, which have determined the locations of settlements, the pattern of roads, the geostamps® and the division of the land in Anatolia, are an unknown aspect of the ancient era. In response to the obscurity of the topic, this paper sets out to make a preliminary appraisal of the grids of the ancient era. With the aid of a multi-disciplinary approach, an inter-disciplinary methodology and the Google Earth software, it outlines some of the types of grid that it has been possible to identify from analyses and drawings of the geography of Anatolia, together with their measures and origins. -

Men and Measures

fl 1 3 0 50 3 7 MEN A ND M EA SU R ES A HISTORY O F W E IG H TS AND M EASU RE S ANCI ENT AND M O D ERN W CH L F SO . S . ED A RD N I O N , C . - S U RG E O N L IEU T . C OL ONE L ARM Y M E D IC AL DE PA RTM E NT A U T H O R ox? A M A NU AL or IND IA N O PH IOL OG Y “ ’ ‘ ' ' TH E ST ORY or ov a wmcur s A ND mzA suax s rno unzro DE Pnouv to Erc. LONDON S E O 1 W C . MITH, LDER , 5 ATERLOO PLACE 1 9 1 2 P R E FA C E THIS history is the development of a short story of the Imperial System of Weights and Measures pub E R RA TA . A ND EA U RE M S S. P R E FA C E THIS history is the development of a short story of the Imperial System of Weights and Measures pub lished eleven years ago , but withdrawn when this all fuller work took shape . To have made it at com plete would have required a long lifetime of research s to give and discu s every authority, to trace , even to acknowledge , every source of information would have unduly swollen the volume and slackened the interest i ts of the narrative . I offer it w th all i shortcomings as an attempt to show the metric instincts of man t everywhere and in all ime , to trace the origins and evolution of the main national systems , to explain the apparently arbitrary changes which have affected e them , to show how the anci nt system used by the - English speaking peoples of the world has been able , not only to survive dangerous perturbations in the past , but also to resist the modern revolutionary system which has destroyed so many others less s homogeneous , le s capable of adaptation to circum t s ances .