How Does Arctic Sea Ice Form and Decay - Wadhams

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Numerical Modelling of Snow and Ice Thicknesses in Lake Vanajavesi, Finland

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk SERIES A brought to you by CORE DYNAMIC METEOROLOGY provided by Helsingin yliopiston digitaalinen arkisto AND OCEANOGRAPHY PUBLISHED BY THE INTERNATIONAL METEOROLOGICAL INSTITUTE IN STOCKHOLM Numerical modelling of snow and ice thicknesses in Lake Vanajavesi, Finland By YU YANG1,2*, MATTI LEPPA¨ RANTA2 ,BINCHENG3,1 and ZHIJUN LI1, 1State Key Laboratory of Coastal and Offshore Engineering, Dalian University of Technology, Dalian 116024, China; 2Department of Physics, University of Helsinki, PO Box 48, FI-00014 Helsinki, Finland; 3Finnish Meteorological Institute, PO Box 503, FI-00101, Helsinki, Finland (Manuscript received 27 March 2011; in final form 7 January 2012) ABSTRACT Snow and ice thermodynamics was simulated applying a one-dimensional model for an individual ice season 2008Á2009 and for the climatological normal period 1971Á2000. Meteorological data were used as the model input. The novel model features were advanced treatment of superimposed ice and turbulent heat fluxes, coupling of snow and ice layers and snow modelled from precipitation. The simulated snow, snowÁice and ice thickness showed good agreement with observations for 2008Á2009. Modelled ice climatology was also reasonable, with 0.5 cm d1 growth in DecemberÁMarch and 2 cm d1 melting in April. Tuned heat flux from waterto ice was 0.5 W m 2. The diurnal weather cycle gave significant impact on ice thickness in spring. Ice climatology was highly sensitive to snow conditions. Surface temperature showed strong dependency on thickness of thin ice (B0.5 m), supporting the feasibility of thermal remote sensing and showing the importance of lake ice in numerical weather prediction. -

SAR Image Wave Spectra to Retrieve the Thickness of Grease-Pancake

www.nature.com/scientificreports OPEN SAR image wave spectra to retrieve the thickness of grease‑pancake sea ice using viscous wave propagation models Giacomo De Carolis 1*, Piero Olla2,3 & Francesca De Santi 1 Young sea ice composed of grease and pancake ice (GPI), as well as thin foes, considered to be the most common form of sea ice fringing Antarctica, is now becoming the “new normal” also in the Arctic. A study of the rheological properties of GPI is carried out by comparing the predictions of two viscous wave propagation models: the Keller model and the close‑packing (CP) model, with the observed wave attenuation obtained by SAR image techniques. In order to ft observations, it is shown that describing GPI as a viscous medium requires the adoption of an ice viscosity which increases with the ice thickness. The consequences regarding the possibility of ice thickness retrieval from remote sensing data of wave attenuation are discussed. We provide examples of GPI thickness retrievals from a Sentinel‑1 C band SAR image taken in the Beaufort Sea on 1 November 2015, and three CosmoSkyMed X band SAR images taken in the Weddell Sea on March 2019. The estimated GPI thicknesses are consistent with concurrent SMOS measurements and available local samplings. Climate change has led in the last decade to a dramatic reduction in the extent and the thickness of sea ice in the Arctic region during the summer season. As a result, the marginal ice zone (MIZ), which is the dynamic transition region separating the ice pack from the open ocean, has become increasingly exposed to the wind and the wave actions1,2. -

30-2 Lee2.Pdf

OceTHE OFFICIALa MAGAZINEn ogOF THE OCEANOGRAPHYra SOCIETYphy CITATION Lee, C.M., J. Thomson, and the Marginal Ice Zone and Arctic Sea State Teams. 2017. An autonomous approach to observing the seasonal ice zone in the western Arctic. Oceanography 30(2):56–68, https://doi.org/10.5670/oceanog.2017.222. DOI https://doi.org/10.5670/oceanog.2017.222 COPYRIGHT This article has been published in Oceanography, Volume 30, Number 2, a quarterly journal of The Oceanography Society. Copyright 2017 by The Oceanography Society. All rights reserved. USAGE Permission is granted to copy this article for use in teaching and research. Republication, systematic reproduction, or collective redistribution of any portion of this article by photocopy machine, reposting, or other means is permitted only with the approval of The Oceanography Society. Send all correspondence to: [email protected] or The Oceanography Society, PO Box 1931, Rockville, MD 20849-1931, USA. DOWNLOADED FROM HTTP://TOS.ORG/OCEANOGRAPHY SPECIAL ISSUE ON AUTONOMOUS AND LAGRANGIAN PLATFORMS AND SENSORS (ALPS) An Autonomous Approach to Observing the Seasonal Ice Zone in the Western Arctic By Craig M. Lee, Jim Thomson, and the Marginal Ice Zone and Arctic Sea State Teams 56 Oceanography | Vol.30, No.2 ABSTRACT. The Marginal Ice Zone and Arctic Sea State programs examined the MIZ is a region of complex atmosphere- processes that govern evolution of the rapidly changing seasonal ice zone in the Beaufort ice-ocean dynamics that varies with sea Sea. Autonomous platforms operating from the ice and within the water column ice properties and distance from the ice collected measurements across the atmosphere-ice-ocean system and provided the edge (Figure 2; e.g., Morison et al., 1987). -

Drift of Pancake Ice Floes in the Winter Antarctic Marginalicezoneduringpolarcyclones

DRIFT OF PANCAKE ICE FLOES IN THE WINTER ANTARCTIC MARGINAL ICE ZONE DURING POLAR CYCLONES APREPRINT Alberto Alberello∗ Luke Bennetts Petra Heil University of Adelaide University of Adelaide Australian Antarctic Division & ACE–CRC 5005, Adelaide, Australia 5005, Adelaide, Australia 7001, Hobart, Australia Clare Eayrs Marcello Vichi Keith MacHutchon New York University Abu Dhabi University of Cape Town University of Cape Town Abu Dhabi, United Arab Emirates Rondenbosch, 7701, South Africa Rondenbosch, 7701, South Africa Miguel Onorato Alessandro Toffoli Università di Torino & IFNF The University of Melbourne Torino, 10125, Italy 3010, Parkville, Australia June 27, 2019 ABSTRACT High temporal resolution in–situ measurements of pancake ice drift are presented, from a pair of buoys deployed on floes in the Antarctic marginal ice zone during the winter sea ice expansion, over nine days in which the region was impacted by four polar cyclones. Concomitant measurements of wave-in-ice activity from the buoys is used to infer that pancake ice conditions were maintained over at least the first seven days. Analysis of the data shows: (i) unprecedentedly fast drift speeds in the Southern Ocean; (ii) high correlation of drift velocities with the surface wind velocities, indicating absence of internal ice stresses >100 km in from the edge in 100% remotely sensed ice concentration; and (iii) presence of a strong inertial signature with a 13 h period. A Langrangian free drift model is developed, including a term for geostrophic currents that reproduces the 13 h period signature in the ice motion. The calibrated model is shown to provide accurate predictions of the ice drift for up to 2 days, and the calibrated parameters provide estimates of wind and ocean drag for pancake floes under storm conditions. -

2Growth, Structure and Properties of Sea

Growth, Structure and Properties 2 of Sea Ice Chris Petrich and Hajo Eicken 2.1 Introduction The substantial reduction in summer Arctic sea ice extent observed in 2007 and 2008 and its potential ecological and geopolitical impacts generated a lot of attention by the media and the general public. The remote-sensing data documenting such recent changes in ice coverage are collected at coarse spatial scales (Chapter 6) and typically cannot resolve details fi ner than about 10 km in lateral extent. However, many of the processes that make sea ice such an important aspect of the polar oceans occur at much smaller scales, ranging from the submillimetre to the metre scale. An understanding of how large-scale behaviour of sea ice monitored by satellite relates to and depends on the processes driving ice growth and decay requires an understanding of the evolution of ice structure and properties at these fi ner scales, and is the subject of this chapter. As demonstrated by many chapters in this book, the macroscopic properties of sea ice are often of most interest in studies of the interaction between sea ice and its environment. They are defi ned as the continuum properties averaged over a specifi c volume (Representative Elementary Volume) or mass of sea ice. The macroscopic properties are determined by the microscopic structure of the ice, i.e. the distribution, size and morphology of ice crystals and inclusions. The challenge is to see both the forest, i.e. the role of sea ice in the environment, and the trees, i.e. the way in which the constituents of sea ice control key properties and processes. -

The Roland Von Glasow Air-Sea-Ice Chamber (Rvg-ASIC)

https://doi.org/10.5194/amt-2020-392 Preprint. Discussion started: 14 October 2020 c Author(s) 2020. CC BY 4.0 License. The Roland von Glasow Air-Sea-Ice Chamber (RvG-ASIC): an experimental facility for studying ocean/sea-ice/atmosphere interactions Max Thomas1, James France1,2,3, Odile Crabeck1, Benjamin Hall4, Verena Hof5, Dirk Notz5,6, Tokoloho Rampai4, Leif Riemenschneider5, Oliver Tooth1, Mathilde Tranter1, and Jan Kaiser1 1Centre for Ocean and Atmospheric Sciences, School of Environmental Sciences, University of East Anglia, UK, NR4 7TJ 2British Antarctic Survey, Natural Environment Research Council, Cambridge CB3 0ET, UK 3Department of Earth Sciences, Royal Holloway, University of London, Egham TW20 0EX, UK 4Chemical Engineering Deptartment, University of Cape Town, South Africa 5Max Planck Institute for Meteorology, Hamburg, Germany 6Center for Earth System Research and Sustainability (CEN), University of Hamburg, Germany Correspondence: Jan Kaiser ([email protected]) Abstract. Sea ice is difficult, expensive, and potentially dangerous to observe in nature. The remoteness of the Arctic and Southern Oceans complicates sampling logistics, while the heterogeneous nature of sea ice and rapidly changing environmental conditions present challenges for conducting process studies. Here, we describe the Roland von Glasow Air-Sea-Ice Chamber (RvG-ASIC), a laboratory facility designed to reproduce polar processes and overcome some of these challenges. The RvG- 5 ASIC is an open-topped 3.5 m3 glass tank housed in a coldroom (temperature range: -55 to +30 oC). The RvG-ASIC is equipped with a wide suite of instruments for ocean, sea ice, and atmospheric measurements, as well as visible and UV lighting. -

Chronology, Stable Isotopes, and Glaciochemistry of Perennial Ice in Strickler Cavern, Idaho, USA

Investigation of perennial ice in Strickler Cavern, Idaho, USA Chronology, stable isotopes, and glaciochemistry of perennial ice in Strickler Cavern, Idaho, USA Jeffrey S. Munroe†, Samuel S. O’Keefe, and Andrew L. Gorin Geology Department, Middlebury College, Middlebury, Vermont 05753, USA ABSTRACT INTRODUCTION in successive layers of cave ice can provide a record of past changes in atmospheric circula- Cave ice is an understudied component The past several decades have witnessed a tion (Kern et al., 2011a). Alternating intervals of of the cryosphere that offers potentially sig- massive increase in research attention focused ice accumulation and ablation provide evidence nificant paleoclimate information for mid- on the cryosphere. Work that began in Antarc- of fluctuations in winter snowfall and summer latitude locations. This study investigated tica during the first International Geophysi- temperature over time (e.g., Luetscher et al., a recently discovered cave ice deposit in cal Year in the late 1950s (e.g., Summerhayes, 2005; Stoffel et al., 2009), and changes in cave Strickler Cavern, located in the Lost River 2008), increasingly collaborative efforts to ex- ice mass balances observed through long-term Range of Idaho, United States. Field and tract long ice cores from Antarctica (e.g., Jouzel monitoring have been linked to weather patterns laboratory analyses were combined to de- et al., 2007; Petit et al., 1999) and Greenland (Schöner et al., 2011; Colucci et al., 2016). Pol- termine the origin of the ice, to limit its age, (e.g., Grootes et al., 1993), satellite-based moni- len and other botanical evidence incorporated in to measure and interpret the stable isotope toring of glaciers (e.g., Wahr et al., 2000) and the ice can provide information about changes compositions (O and H) of the ice, and to sea-ice extent (e.g., Serreze et al., 2007), field in surface environments (Feurdean et al., 2011). -

Satellite Observations for Detecting and Forecasting Sea-Ice Conditions: a Summary of Advances Made in the SPICES Project by the EU’S Horizon 2020 Programme

remote sensing Article Satellite Observations for Detecting and Forecasting Sea-Ice Conditions: A Summary of Advances Made in the SPICES Project by the EU’s Horizon 2020 Programme Marko Mäkynen 1,* , Jari Haapala 1, Giuseppe Aulicino 2 , Beena Balan-Sarojini 3, Magdalena Balmaseda 3, Alexandru Gegiuc 1 , Fanny Girard-Ardhuin 4, Stefan Hendricks 5, Georg Heygster 6, Larysa Istomina 5, Lars Kaleschke 5, Juha Karvonen 1 , Thomas Krumpen 5, Mikko Lensu 1, Michael Mayer 3,7, Flavio Parmiggiani 8 , Robert Ricker 4,5 , Eero Rinne 1, Amelie Schmitt 9 , Markku Similä 1 , Steffen Tietsche 3 , Rasmus Tonboe 10, Peter Wadhams 11, Mai Winstrup 12 and Hao Zuo 3 1 Finnish Meteorological Institute, PB 503, FI-00101 Helsinki, Finland; jari.haapala@fmi.fi (J.H.); alexandru.gegiuc@fmi.fi (A.G.); juha.karvonen@fmi.fi (J.K.); mikko.lensu@fmi.fi (M.L.); eero.rinne@fmi.fi (E.R.); markku.simila@fmi.fi (M.S.) 2 Department of Science and Technology—DiST, Università degli Studi di Napoli Parthenope, Centro Direzionale Is C4, 80143 Napoli, Italy; [email protected] 3 European Centre for Medium-Range Weather forecasts, Shinfield Park, Reading RG2 9AX, UK; [email protected] (B.B.-S.); [email protected] (M.B.); [email protected] (M.M.); steff[email protected] (S.T.); [email protected] (H.Z.) 4 Ifremer, Univ. Brest, CNRS, IRD, Laboratoire d’Océanographie Physique et Spatiale, IUEM, 29280 Brest, France; [email protected] 5 AlfredWegener Institute, Am Handelshafen 12, 27570 Bremerhaven, Germany; [email protected] (S.H.); -

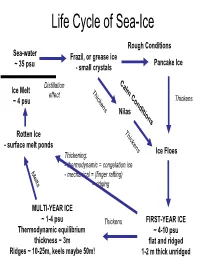

Life Cycle of Sea-Ice

Life Cycle of Sea-Ice Rough Conditions Sea-water Frazil, or grease ice Pancake Ice ~ 35 psu - small crystals C Distillation a Ice Melt T lm effect hi C ~ 4 psu ck o Thickens ens nd Nilas itio ns T hi Rotten Ice c - surface melt ponds kens Ice Floes Thickening: - thermodynamic = congelation ice M e - mechanical = (finger rafting) l ts = ridging MULTI-YEAR ICE ~ 1-4 psu Thickens FIRST-YEAR ICE Thermodynamic equilibrium ~ 4-10 psu thickness ~ 3m flat and ridged Ridges ~ 10-25m, keels maybe 50m! 1-2 m thick unridged Internal Structure of Sea Ice Brine Channels within the ice (~width of human hair) Brine rejected from ice (4-10psu), away from surface, but concentrates in brine channels long crystals as congelation ice (small volume but VERY HIGH SALINITIES) (frozen on from below) -6 deg C -10 deg C -21 deg C 100psu 145psu 216psu Pictures from AWI Brine Volume and Salinity From Thomas and Dieckmann 2002, Science .... adapted from papers by Hajo Eichen Impacts of Sea-ice on the Ocean ICE FORMATION and PRESENCE Wind - brine rejection - Ocean-Atmos momentum barrier - Ocean-Atmos heat barrier - ice edge processes (e.g. upwelling) - keel stirring (i.e. mixing, but < wind) Ocean 10psu MELTING ICE Fresh 35psu - stratification (fresher water) (cf. distillation as ice moves from formation region) Saltier - transport of sediment, etc S increases START FREEZE MELT Impacts of Sea-ice on the Atmosphere ICE PRESENCE - albedo change - Ocean-Atmos momentum barrier - Ocean-Atmos heat barrier Water Sky Sea Smoke Heat balance S=Shortwave radiation from sun (reflects off clouds and surface) albedo= how much radiation reflects from surface albedo of ice ~ 0.8 albedo of water ~ 0.04 (if sun overhead) L=Longwave radiation (from surface and clouds) F=Heat flux from Ocean M=Melt (snow and ice) From N. -

Frazil Ice Formation in the Polar Oceans

Frazil Ice Formation in the Polar Oceans Nikhil Vibhakar Radia Department of Earth Sciences, UCL A thesis submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Supervisor: D. L. Feltham August, 2013 1 I, Nikhil Vibhakar Radia, confirm that the work presented in this thesis is my own. Where information has been derived from other sources, I confirm that this has been indicated in the thesis. SIGNED 2 Abstract Areas of open ocean within the sea ice cover, known as leads and polynyas, expose ocean water directly to the cold atmosphere. In winter, these are regions of high sea ice production, and they play an important role in the mass balance of sea ice and the salt budget of the ocean. Sea ice formation is a complex process that starts with frazil ice crys- tal formation in supercooled waters, which grow and precipitate to the ocean surface to form grease ice, which eventually consolidates and turns into a layer of solid sea ice. This thesis looks at all three phases, concentrating on the first. Frazil ice comprises millimetre- sized crystals of ice that form in supercooled, turbulent water. They initially form through a process of seeding, and then grow and multiply through secondary nucleation, which is where smaller crystals break off from larger ones to create new nucleii for further growth. The increase in volume of frazil ice will continue to occur until there is no longer super- cooling in the water. The crystals eventually precipitate to the surface and pile up to form grease ice. The presence of grease ice at the ocean surface dampens the effects of waves and turbulence, which allows them to consolidate into a solid layer of ice. -

Anchor Ice and Bottom-Freezing in High-Latitude Marine Sedimentary Environments: Observations from the Alaskan Beaufort Sea

ANCHOR ICE AND BOTTOM-FREEZING IN HIGH-LATITUDE MARINE SEDIMENTARY ENVIRONMENTS: OBSERVATIONS FROM THE ALASKAN BEAUFORT SEA by Erk Reimnitz, E. W. Kempema, and P. W. Barnes U.S. Geological Survey Menlo Park, California 94025 Final Report Outer Continental Shelf Environmental Assessment Program Research Unit 205 1986 257 This report has also been published as U.S. Geological Survey Open-File Report 86-298. ACKNOWLEDGMENTS This study was funded in part by the Minerals Management Service, Department of the Interior, through interagency agreement with the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, Department of Commerce, as part of the Alaska Outer Continental Shelf Environmental Assessment Program. We thank D. A. Cacchione for his thoughtful review of the manuscript. TABLE OF CONTENTS Page ACKNOWLEDGMENTS . ...259 INTRODUCTION . 263 REGIONAL SETTING . ...264 INDIRECT EVIDENCE FOR ANCHOR ICE IN THE BEAUFORT SEA . ...266 DIVER OBSERVATIONS OF ANCHOR ICE AND ICE-BONDED SEDIMENTS . ...271 DISCUSSION AND CONCLUSION . ...274 REFERENCES CITED . ...278 INTRODUCTION As early as 1705 sailors observed that rivers sometimes begin to freeze from the bottom (Barnes, 1928; Piotrovich, 1956). Anchor ice has been observed also in lakes and the sea (Zubov, 1945; Dayton, et al., 1969; Foulds and Wigle, 1977; Martin, 1981; Tsang, 1982). The growth of anchor ice implies interactions between ice and the sub- strate, and a marked change in the sedimentary environment. However, while the literature contains numerous observations that imply sediment transport, no studies have been conducted on the effects of anchor ice growth on sediment dynamics and bedforms. Underwater ice is the general term for ice formed in the supercooled water column. -

Observing the Seasonal Ice Zone in the Western Arctic

SPECIAL ISSUE ON AUTONOMOUS AND LAGRANGIAN PLATFORMS AND SENSORS (ALPS) An Autonomous Approach to Observing the Seasonal Ice Zone in the Western Arctic By Craig M. Lee, Jim Thomson, and the Marginal Ice Zone and Arctic Sea State Teams 56 Oceanography | Vol.30, No.2 ABSTRACT. The Marginal Ice Zone and Arctic Sea State programs examined the MIZ is a region of complex atmosphere- processes that govern evolution of the rapidly changing seasonal ice zone in the Beaufort ice-ocean dynamics that varies with sea Sea. Autonomous platforms operating from the ice and within the water column ice properties and distance from the ice collected measurements across the atmosphere-ice-ocean system and provided the edge (Figure 2; e.g., Morison et al., 1987). persistence to sample continuously through the springtime retreat and autumn advance Additionally, the northward retreat of of sea ice. Autonomous platforms also allowed operational modalities that reduced the sea ice exposes an increasing expanse of field programs’ logistical requirements. Observations indicate that thermodynamics, open water south of the ice edge, eventu- especially the radiative balances of the ice-albedo feedback, govern the seasonal cycle ally providing sufficient fetch for the gen- of sea ice, with the role of surface waves confined to specific events. Continuous eration of long-period, large-amplitude sampling from winter into autumn also reveals the imprint of winter ice conditions and waves (e.g., Thomson and Rogers, 2014). fracturing on summertime floe size distribution. These programs demonstrate effective Such waves are capable of propagating use of integrated systems of autonomous platforms for persistent, multiscale Arctic north and penetrating into the pack to observing.