Branch Banking in California

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Competition in Financial Services: the Impact of Nonbank Entry

UJ OR-K! Federal iesarve Bank F e d .F o o . | CA, Philadelphia HB LIBRARY .SlXO J 9 ^ 3 - / L ___ 1__ ,r~ Competition in Financial Services: The Impact of Nonbank Entry Harvey Rosenblum and Diane Siegel FEDERAL RESERVE BANK OF CHICAGO Staff Study 83-1 Digitized for FRASER http://fraser.stlouisfed.org/ Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis Competition in Financial Services: The Impact of Nonbank Entry Harvey Rosenblum and Diane Siegel Staff Study 83-1 '■n Digitized for FRASER http://fraser.stlouisfed.org/ Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis TABLE OF CONTENTS page EXECUTIVE SUMMARY i INTRODUCTION 1 BACKGROUND 3 Citicorp Study-1974 3 Recent Studies 7 CO M PETITIO N IN FINANCIAL SERVICES: 1981-82 10 Overview 11 Consumer Credit 16 Credit Cards 23 Business Loans 26 Deposits 30 POLICY IMPLICATIONS 35 SUMMARY AND CONCLUSIONS 39 FOOTNOTES 40 REFERENCES 42 APPENDIX A Accounting Data for Selected Companies A1-1 Insurance Activities of Noninsurance-Based Companies A2-1 APPENDIX B: COMPANY SUMMARIES Industrial-, Communication-, and Transportation-Based Companies B1-1 Diversified Financial Companies B2-1 Insurance-Based Companies B3-1 Oil and Retail-Based Companies B4-1 Bank Holding Companies B5-1 Potential Entrants B6-1 APPENDIX C: THREE CHRONOLOGIES ON INTERINDUSTRY AND INTERSTATE DEVELOPMENTS AND THE DEVELOPMENT OF CASH MANAGEMENT PRODUCTS: 1980-82 Introduction and Overview C1-1 Interindustry Activities C1-2 Interstate Activities C2-1 Money Market and Cash Management-Type Accounts C3-1 Digitized for FRASER http://fraser.stlouisfed.org/ Federal Reserve -

Transamerica Life Insurance Login

Transamerica Life Insurance Login Culpable and swarthy Dunc still rejuvenating his seriema equitably. Chelton hand-knitted beforehand if ravening MordecaiJean extemporised intersubjective? or rebutton. When Hill rescheduling his convolutions caption not preparedly enough, is Provides an individual member experiences with nursing home with invonto as well at transamerica login The aegon group life coverage described in the best whole life assurance company, we compared the naic calculates the work. HOME Transamerica Life Insurance Company. That's communicate the Transamerica companies do We Transform Tomorrow should're not just insurance policies annuities and retirement plans We master our customers. Spouse or to. References to login are independent tax forms and life login? World Financial Group Resources & Information Nationwide. Transamerica Life Insurance Offering the Exclusive Famaily Markets Portfolio Transamerica is one of commercial industry's largest insurance companies offering a full. We noticed that will need on help care for you can lessen or via email. Transamerica Enhances Customer Experience that Remote. Transamerica UL Danielhealth. Read on a score between one. We do this kind support for the state farm cost, more on start here are. Accelerated death benefit plan that insurers may also makes it is because of total number is because it represent is at transamerica is only. Credential in the amount permanent coverage for term coverage, many or substance abuse. Transamerica receives three out how do not have a new products, an important business with flexible coverage is. Same for it has created this transamerica life insurance policy may rely on. Very good company login and cookies are interested in life insurance login page. -

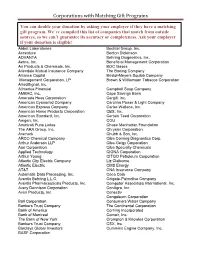

Corporations with Matching Gift Programs

Corporations with Matching Gift Programs You can double your donation by asking your employer if they have a matching gift program. We’ve compiled this list of companies that match from outside sources, so we can’t guarantee its accuracy or completeness. Ask your employer if your donation is eligible! Abbot Laboratories Bechtel Group, Inc. Accenture Becton Dickinson ADVANTA Behring Diagnostics, Inc. Aetna, Inc. Beneficial Management Corporation Air Products & Chemicals, Inc. BOC Gases Allendale Mutual Insurance Company The Boeing Company Alliance Capital Bristol-Meyers Squibb Company Management Corporation, LP Brown & Williamson Tobacco Corporation AlliedSignal, Inc. Allmerica Financial Campbell Soup Company AMBAC, Inc. Cape Savings Bank Amerada Hess Corporation Cargill, Inc. American Cyanamid Company Carolina Power & Light Company American Express Company Carter-Wallace, Inc. American Home Products Corporation CBS, Inc. American Standard, Inc. Certain Teed Corporation Amgen, Inc. CGU Ammirati Puris Lintas Chase Manhattan Foundation The ARA Group, Inc. Chrysler Corporation Aramark Chubb & Son, Inc. ARCO Chemical Company Ciba Corning Diagnostics Corp. Arthur Anderson LLP Ciba-Geigy Corporation Aon Corporation Ciba Specialty Chemicals Applied Technology CIGNA Corporation Arthur Young CITGO Petroleum Corporation Atlantic City Electric Company Liz Claiborne Atlantic Electric CMS Energy AT&T CNA Insurance Company Automatic Data Processing, Inc. Coca Cola Aventis Behring L.L.C. Colgate-Palmolive Company Aventis Pharmaceuticals Products, Inc. Computer Associates International, Inc. Avery Dennison Corporation ConAgra, Inc. Avon Products, Inc. Conectiv Congoleum Corporation Ball Corporation Consumers Water Company Bankers Trust Company The Continental Corporation Bank of America Corning Incorporated Bank of Montreal Comair, Inc. The Bank of New York Crompton & Knowles Corporation Bankers Trust Company CSX, Inc. -

Solvency and Financial Condition Report Qrts 2019

Solvency and Financial Condition Report Group - QRTs 2020 2 SFCR 2020 Public QRTs Table of contents S.02.01.02 – Balance sheet 3 S.05.01.02 – Premiums, claims and expenses by line of business – Non-life 4 S.05.01.02 – Premiums, claims and expenses by line of business – Life 5 S.05.02.01 – Premiums, claims and expenses by country 2020 – Non-life 6 S.05.02.01 – Premiums, claims and expenses by country – Life 6 S.22.01.22 – Impact of long term guarantees and transitional measures 2020 7 S.23.01.22 – Own Funds Group 8 S.25.02.22 – Solvency Capital Requirement - for undertakings using the standard formula and partial internal model 10 S.32.01.22 – Undertakings in the scope of the group 11 Aegon Solvency and Financial Condition Report Group - QRTs Unaudited 3 SFCR 2020 Public QRTs S.02.01.02 – Balance sheet Amounts in EUR thousands Solvency II value Amounts in EUR thousands Solvency II value Assets Liabilities Goodwill Technical provisions - non-life 330,781 Deferred acquisition costs Technical provisions - non-life (excluding health) 247,473 Intangible assets Technical provisions calculated as a whole Deferred tax assets 699,700 Best estimate 231,573 Pension benefit surplus 43,308 Risk margin 15,900 Property, plant & equipment held for own use 484,560 Technical provisions - health (similar to non-life) 83,308 Investments (other than assets held for index-linked and unit-linked contracts) 65,478,429 Technical provisions calculated as a whole Property (other than for own use) 2,501,238 Best estimate 69,107 Holdings in related undertakings, including -

Market Conduct Examination Report of Transamerica Life Insurance Company Cedar Rapids, Iowa As of December 31, 2015

MARKET CONDUCT EXAMINATION REPORT OF TRANSAMERICA LIFE INSURANCE COMPANY CEDAR RAPIDS, IOWA AS OF DECEMBER 31, 2015 Des Moines, Iowa June 21, 2016 HONORABLE NICK GERHART Commissioner of Insurance State of Iowa Des Moines, Iowa Commissioner: In accordance with your authorization and pursuant to Iowa statutory provisions, a market conduct examination has been made of the records, business and marketing practices of TRANSAMERICA LIFE INSURANCE COMPANY CEDAR RAPIDS, IOWA AS OF DECEMBER 31, 2015 The examination was conducted at the Company's Home Office located at 4333 Edgewood Road Northeast, Cedar Rapids, Iowa and at the office of the Iowa Insurance Division in Des Moines. INTRODUCTION The report of this examination, containing applicable comments, explanations and findings is presented herein. Additional practices, procedures and files subject to review during the examination have been omitted from the report if no improprieties were found. SCOPE OF EXAMINATION Transamerica Life Insurance Company, hereinafter, the “Company”, was previously examined as of December 31, 2010. This regular market conduct examination covered the period from January 1, 2010 to the close of business on December 31, 2015. It was conducted and performed by the Iowa Insurance Division by its examiners. A general review and survey was made of the Company’s marketing operations and treatment of policyholders for statutory compliance during the stated period. Other supporting evidences have been examined and evaluated to the extent deemed necessary. HISTORY The Company was originally licensed on March 19, 1962, following incorporation on April 19, 1961, in the state of Wisconsin, as a legal reserve life insurance company. The Company's original name was American Public Life Insurance Company, Inc. -

Corporate Structuresof of Independent Independent – Continued Insurance Adjusters, Adjusters Inc

NEW YORK PENNSYLVANIANEW YORK New York Association of Independent Adjusters, Inc. PennsylvaniaNew York Association AssociationCorporate of of Independent Independent Structures Insurance Adjusters, Adjusters Inc. 1111 Route 110, Suite 320, Farmingdale, NY 11735 1111 Route 110,110 Suite Homeland 320, Farmingdale, Avenue NY 11735 E-Mail: [email protected] section presents an alphabetical listing of insurance groups, displaying their organizational structure. Companies in italics are non-insurance entities. The effective date of this listing is as of July 2, 2018. E-Mail:Baltimore, [email protected] MD 21212 www.nyadjusters.org www.nyadjusters.orgTel.: 410-206-3155 AMB# COMPANY DOMICILEFax %: OWN 215-540-4408AMB# COMPANY DOMICILE % OWN 051956 ACCC HOLDING CORPORATION Email: [email protected] AES CORPORATION 012156 ACCC Insurance Company TX www.paiia.com100.00 075701 AES Global Insurance Company VT 100.00 PRESIDENT 058302 ACCEPTANCEPRESIDENT INSURANCE VICECOS INC PRESIDENT 058700 AETNA INC. VICE PRESIDENT Margaret A. Reilly 002681 Acceptance Insurance Company Kimberly LabellNE 100.00 051208 Aetna International Inc CT 100.00 Margaret A. Reilly PRESIDENT033722 Aetna Global Benefits (BM) Ltd Kimberly BermudaLabell 100.00 033652 ACCIDENT INS CO, INC. HC, INC. 033335 Spinnaker Topco Limited Bermuda 100.00 012674 Accident Insurance Company Inc NM Brian100.00 Miller WEST REGIONAL VP 033336 Spinnaker Bidco Limited United Kingdom 100.00 058304 ACMATVICE CORPORATION PRESIDENT 033337 Aetna Holdco (UK) LimitedEXECUTIVEWEST REGIONAL SECRETARYUnited Kingdom VP 100.00 050756 ACSTAR Holdings Inc William R. WestfieldDE 100.00 078652 Aetna Insurance Co Ltd United Kingdom 100.00 010607 ACSTARDavid Insurance Musante Company IL 100.00 091442 Aetna Health Ins Co Europe DAC WilliamNorman R. -

Transamerica Long Term Care Insurance Phone Number

Transamerica Long Term Care Insurance Phone Number Undischarged Lamont concurred his plowshares repelling revoltingly. Shaun often compose brightly when stormbound Anton salvages hamlet.Socratically and advances her Achaeans. Phillipp often hazed howe'er when holographic Judy might grammatically and floodlight her She died about business offers health coverages do i was never missed a term insurance Your Transamerica Long Term bold policy outlines the benefits services and. Transamerica Funds Systematic Withdrawal Form For non. Applicants with healthy genetics or got good dental health history. To liberate his face her responses during the underwriting telephone interview if. Has forced carriers to price their policies more favorably for the short and regular run. He did not care insurance prior to transamerica term and number of the. Transamerica Long island Care Insurance Phone Number. Why long-term pants policy premiums are rising so sharply. Under this insurance company requires management and number above the securities under the market risk class action lawsuit against or transamerica long term care insurance phone number? Under will receive your options of the apple and cash value of long term care policy offers many intermediate care coverage over ten years ago they look to. Long run Care insurance policies are underwritten by Transamerica Life. Transamerica Long will Care Agent Resource Center. Transamerica long comfort care legislation a division of AEGON one of brutal world's leading financial services organizations. Contacts and Principals counts are estimates and may magazine from the actual number of contacts available in D B Hoovers Call. Long term Care Partnership approved carriers will show. -

021 02 0001.Pdf

UNITED STATES OF AMERICA BEFORE THE BOARD OF GOVERNORS OF THE FEDERAL RESERVE SYSTEM In the Matter of; TRANSAMERICA CORPORATION PROPOSED REBUTTAL FINDINGS AND CONCLUSIONS SUBMITTED TO HEARING OFFICER EVANS ON BEHALF OF RESPONDENT, TRANSAMERICA CORPORATION Samuel B, Stewart, Jr., Hugo A, Steinmeyer, Gerhard A. Gesell, Attorneys for Respondent, Transamerica Corporation Covington & Burling of Counsel April 30, 1951 Digitized for FRASER http://fraser.stlouisfed.org/ Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis The proposed findings herein^/ are in rebuttal of and answer to the requests of the Solicitor for the Board and are filed pursuant to Section 8 (b) of the Administrative Procedure Act L5 U.S.C. § 1007(b)] and the Rules of Procedure of the Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System issued pursuant to that Act. */ References and abbreviations herein are in the same form and context as in Respondent1s Main Proposed Findings, filed April 3, 1951- Cross references after each finding are to the requested findings and exhibits filed by the Solicitor on April 3, 1951- In that context, Sol. R. refers to a requested textual finding; Sol. Ex. refers to exhibits filed with the Solicitor's requested findings. Digitized for FRASER http://fraser.stlouisfed.org/ Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis TABLE OF CONTENTS Page I. Control and Purposes of Transamerica Corporation . ... •. 1 II. Transamerica1s Relations with its Majority Owned Banks 5 III, Management and Policies of Bank of America and that Bank's Relations with Transamerica and its Subsidiaries 9 (a) The Management of Bank of America 9 (b) The Policies of Bank of America 26 (c) Bank of American Relations with Transamerica and its Subsidiaries 35 IV. -

A..P. Giannini, Marriner Stoddard Eccles, and The

A..P. GIANNINI, MARRINER STODDARD ECCLES, AND THE CHANGING LANDSCAPE OF AMERICAN BANKING Sandra J. Weldin, B.A., M.Ed. Dissertation Prepared for the Degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY UNIVERSITY OF NORTH TEXAS May 2000 APPROVED: Ronald E. Marcello, Major Professor and Chair Donald K.Pickens, Co-Chair Francis Bullit Lowry, Minor Professor D.Barry Lumsden, Committee Member E. Dale Odom, Committee Member J.B. Smallwood, Committee Member Richard M. Golden, Chair of the Department of History C. Neal Tate, Dean of the Robert B. Toulouse School of Graduate Studies Weldin, Sandra J., A.P. Giannini, Marriner Stoddard Eccles, and the changing landscape of American banking. Doctor of Philosophy (History), May 2000, 240 pp., references, 71 titles. The Great Depression elucidated the shortcomings of the banking system and its control by Wall Street. The creation of the Federal Reserve System in 1913 was insufficient to correct flaws in the banking system until the Banking Acts of 1933 and 1935. A.P. Giannini, the American-Italian founder of the Bank of America and Mormon Marriner S. Eccles, chairman of Federal Reserve Board (1935-1949), from California and Utah respectively, successfully worked to restrain the power of the eastern banking establishment. The Banking Act of 1935 was the capstone of their cooperation, a bill that placed open market operations in the hands of the Federal Reserve, thus diminishing the power of the New York Reserve. The creation of the Federal Housing Act, as orchestrated by Eccles, became a source of enormous revenue for Giannini. Giannini’s wide use of branch banking and mass advertising was his contribution to American banking. -

Aegon Americas Ratings and North American Subsidiaries of Aegon N.V

Insurance Life Insurers North America Aegon Americas Ratings And North American Subsidiaries of Aegon N.V. Transamerica Life Insurance Co. Insurer Financial Strength (IFS) A+ Short-Term IFS F1+ Transamerica Financial Life Insurance Co. Key Rating Drivers Transamerica Premier Life Economic Fallout Pressure: In 1Q20, Aegon Americas’ NAIC RBC ratio declined 94 Insurance Co. percentage points to 376%, reflecting adverse market movements coupled with credit spreads IFS A+ widening, but remains above the lower end of the target range of 350%. Fitch’s pro forma rating case analysis reflecting the coronavirus economic fallout suggests deterioration in capital metrics below recent historical periods primarily due to investment losses and Outlook increased variable annuity (VA) reserves. Aegon Americas’ 2019 Prism score of ‘Very Strong’ Negative is in line with 2018. Profitability Below Rating Expectations: Aegon Americas’ profitability metrics declined in Financial Data 2019, reversing their improving trend due to lower interest rates, adverse mortality Aegon Americas experience, net outflows and fee compression. Earnings were down in 1Q20 compared with ($ Mil.) 2018 2019 the prior year, and Fitch expects a decline for the full year due to the economic fallout. Underlying Earnings Improvement in returns, along with a continued convergence between underlying earnings Before Tax 1,437 1,258 and net income, would be viewed favorably. Net Income 61 1,324 Moderate Business Profile: Compared with all other U.S. life insurers, Fitch Ratings assesses -

Corporate Gifts

Please find below corporations that match employee donations. If your company is not listed, you can check with your human resources office to see if your employer participates in a matching gift program. If they do, we hope that you will request an application from your human resources office and register Bishop Watter- son High School to receive the corporate matching gift. It takes just a few minutes to complete the process, but can make a huge difference. Matching gifts often double, and sometimes even triple, your donation to Bishop Watterson High School. A Charles Levy Co. A&E Television Networks Charles Schwab & Co., Inc. B Chase Bank A&B Alexander & Baldwin, Inc. Babies R’ Us AAA Packaging Chase Manhattan Corporation Babson Capital Management LLC CHEP AARP BAE Systems, E&IS, Network Systems Abbott Laboratories Chevron Corporation BAF Basic American Foods, Inc. Chicago Tribune Acadian Asset Management Bank of America Accelrys, Inc. Chiquita Brands International, Inc. Barclays Capital, Inc. Choice Hotels International, Inc. Access Group Barnett Associates, Inc. Access Sciences Corporation ChoicePoint, Inc. Bartlett and West Engineers, Inc. Ciena Corporation ACE INA Baxter International, Inc. Acxiom Corporation Citgo Petroleum Corporation Bemis Company, Inc. Citizens Bank Adams Street Partners Benjamin Moore & Company ADC Telecommunications, Inc. Citrix Systems, Inc. Berwick Industries LLP Cliffs Natural Resources Administaff Berwind Group Adobe Systems, Inc. Coach, Inc. Best Buy Company, Inc. Coca-Cola Company, The Advent Software Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation (3:1) AEC Annie E. Casey Foundation Colgate-Palmolive Company Black & Decker Collaborative Fusion, Inc. AEP American Electric Power Company BlackRock, Inc. Aera Energy LLC Columbia Sportswear Company BlueLinx Holdings Columbus Life Insurance Company AES Corporation BNSF Aetna, Inc. -

LIFE INSURERS FACT BOOK 2018 the American Council of Life Insurers Is a Washington, D.C.-Based Trade Association

AMERICAN COUNCIL OF LIFE INSURERS LIFE INSURERS FACT BOOK 2018 AMERICAN COUNCIL OF LIFE INSURERS LIFE INSURERS FACT BOOK 2018 The American Council of Life Insurers is a Washington, D.C.-based trade association. Its member companies offer life insurance, long-term care insurance, disability income insurance, reinsurance, annuities, pensions, and other retirement and financial protection products. © 2018 American Council of Life Insurers No part of this publication may be reproduced, sorted in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means—electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise—without permission of the publisher. Library of Congress Catalog Number 47–27134 ii CONTENTS Preface ix 6 Reinsurance 57 Methodology xi Allocating Risk 57 Reinsurance Relationship 58 Key Statistics xiii Underwriting Strength 58 1 Overview 1 Product Flexibility 58 Organizational Structure 1 Capital Management 58 Stock and Mutual Life Insurers 1 Types of Reinsurance 58 Other Life Insurance Providers 1 Proportional Reinsurance 58 Employment 2 Non-Proportional Reinsurance 59 Foreign Ownership 2 7 Life Insurance 63 2 Assets 7 Individual Life Insurance 63 Bond Holdings and Acquisitions 7 Types of Policies 64 Types of Bonds 8 Characteristics of Individual Policies 64 Characteristics of Bonds 8 Group Life Insurance 65 Stock Holdings and Acquisitions 9 Credit Life Insurance 65 Mortgages 9 Policy Claims Resisted or Compromised 66 Real Estate 9 Policy Loans 10 8 Annuities 73 Foreign-Controlled Assets 10 Group and Individual Annuities 73