KFRI Research Report No.292 ETHNOZOOLOGICAL STUDIES ON

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Accused Persons Arrested in Palakkad District from 25.08.2019To31.08.2019

Accused Persons arrested in Palakkad district from 25.08.2019to31.08.2019 Name of Name of the Name of the Place at Date & Arresting Court at Sl. Name of the Age & Cr. No & Sec Police father of Address of Accused which Time of Officer, which No. Accused Sex of Law Station Accused Arrested Arrest Rank & accused Designation produced 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 Cr 644/19 U/s Bechamary, Nagayon, R.Renjith, SI of 1 Abdul Mannan Akbar Ali 27 Town South PS 25.08.19 324,75 Of JJ Town South JFCM III Court Assam Police Act Chandrika Vihar, Cr 647/19 U/s R.Renjith, SI of Bailed By 2 Akhil Kumar Manikandan 29 Ramassery, Elapully, Chirakkad 27.08.2019 27(b) of NDPS Town South Police Police Palakkad Act Ayyapankavu Veedu, Cr 647/19 U/s R.Renjith, SI of Bailed By 3 Arun kumar Ayyappan 30 Karingarapully, Chirakkad 27.08.2019 27(b) of NDPS Town South Police Police kodumbu Act ATR Street, Cr 647/19 U/s R.Renjith, SI of Bailed By 4 Ramesh Subramaniyan 30 Kunnathurmedu, Chirakkad 27.08.2019 27(b) of NDPS Town South Police Police palakkad Act Manjode, Cr 619/19 U/s R.Renjith, SI of Bailed By 5 Sethu Chamimala 48 Town south PS 27.08.2019 Town South Thathamangalam 279, 338 IPC Police Police Manakkathodi , Cr 633/19 U/s Jishanu @ Abdul Rasheed, 6 GOPI 24 vadakanthara, Town south PS 29.08.2019 341,323,324,32 Town South CJM Court Upasana SI of Police Palakkad 6 r/w 34 IPC Kallathan Veedu, Cr 654/19 U/s Ramesh, ASI of Bailed By 7 Saravanan Krishnan 28 Kodumbu 30.08.2019 Town South Kodumbu, Palakkad 151 CrPC Police Police 3/2, T Kottampetty, Cr 654/19 U/s Ramesh, ASI -

A CONCISE REPORT on BIODIVERSITY LOSS DUE to 2018 FLOOD in KERALA (Impact Assessment Conducted by Kerala State Biodiversity Board)

1 A CONCISE REPORT ON BIODIVERSITY LOSS DUE TO 2018 FLOOD IN KERALA (Impact assessment conducted by Kerala State Biodiversity Board) Editors Dr. S.C. Joshi IFS (Rtd.), Dr. V. Balakrishnan, Dr. N. Preetha Editorial Board Dr. K. Satheeshkumar Sri. K.V. Govindan Dr. K.T. Chandramohanan Dr. T.S. Swapna Sri. A.K. Dharni IFS © Kerala State Biodiversity Board 2020 All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, tramsmitted in any form or by any means graphics, electronic, mechanical or otherwise, without the prior writted permission of the publisher. Published By Member Secretary Kerala State Biodiversity Board ISBN: 978-81-934231-3-4 Design and Layout Dr. Baijulal B A CONCISE REPORT ON BIODIVERSITY LOSS DUE TO 2018 FLOOD IN KERALA (Impact assessment conducted by Kerala State Biodiversity Board) EdItorS Dr. S.C. Joshi IFS (Rtd.) Dr. V. Balakrishnan Dr. N. Preetha Kerala State Biodiversity Board No.30 (3)/Press/CMO/2020. 06th January, 2020. MESSAGE The Kerala State Biodiversity Board in association with the Biodiversity Management Committees - which exist in all Panchayats, Municipalities and Corporations in the State - had conducted a rapid Impact Assessment of floods and landslides on the State’s biodiversity, following the natural disaster of 2018. This assessment has laid the foundation for a recovery and ecosystem based rejuvenation process at the local level. Subsequently, as a follow up, Universities and R&D institutions have conducted 28 studies on areas requiring attention, with an emphasis on riverine rejuvenation. I am happy to note that a compilation of the key outcomes are being published. -

Accused Persons Arrested in Palakkad District from 28.01.2018 to 03.02.2018

Accused Persons arrested in Palakkad district from 28.01.2018 to 03.02.2018 Name of Name of the Name of the Place at Date & Arresting Court at Sl. Name of the Age & Cr. No & Sec Police father of Address of Accused which Time of Officer, which No. Accused Sex of Law Station Accused Arrested Arrest Rank & accused Designation produced 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 Shahul Mayiladumthurai, 129/18 U/s 151 Town South Bailed by 1 Ganesan Viswanathan 38 Sulthapetta JN 28.01.18 Hameed, GSI Thanjavoor CrPC PS Police of Police 69, Lakshamveedu, Shahul 130/18 U/s 151 Town South Bailed by 2 Nazarudheen Basheer 49 Sundaram Colony, Sulthapetta JN 28.01.18 Hameed, GSI CrPC PS Police Sankuvarathode of Police 44/451, MC Road, 131/18 U/s 279 Shahul Radhakrishna Town South Bailed by 3 Natarajan 48 Chakkanthara, I/F Town Hall 28.01.18 IPC & 3 (1) r/w Hameed, GSI n PS Police Palakkad 181 MV Act of Police 133/18 U/s 15 Shahul Vadaparambu, Town South Bailed by 4 Saju Achuthan 34 Thirunellayi 29.01.18 ( c ) r/w 63 of Hameed, GSI Kannadi, Thirunellayi PS Police Abkari Act of Police Shahul Chungath House, 134/18 U/s 118 Town South Bailed by 5 Ganesan Manikutty 41 Thirunellayi 29.01.18 Hameed, GSI Tirunellayi, Palakkad (a) KP Act PS Police of Police 135/18 U/s 279 Shahul Muraleedhara Chemmankadu, Town South Bailed by 6 Kunju 45 Koottupatha 29.01.18 IPC & 3 (1) r/w Hameed, GSI n Kottekkad PS Police 181 MV Act of Police 136/18 U/s 15 Shahul Athikkodeparambu, Town South Bailed by 7 Prasad Velayudhan 36 Thirunellayi 29.01.18 ( c ) r/w 63 of Hameed, GSI Thirunellayi, Palakkad -

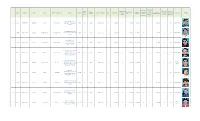

ADIP Beneficiary Data 2017-18

Boarding Travel cost Age / Fabrication/ and No. of days whether Monthly Total Cost of Subsidy paid to out Totel of State District Date Name Father's / Husband's Address Gender Birth Type of Aid Given Qty. Cost of Aid Fitment Loadging for which accompanie Category PHOTO Income Aid Provided station (12+13+14+15) Year Charge Expences stayed d by escort beneficiary paid Puthenpeedika, Tana, 1 Kerala Malappuram 10-01-18 Nuhman Muhammed Pullippadam, Malappuram- Male 16 2,666 TLM 12 - 18 1 6,140.00 0 6140.00 6,140.00 0 0 6,140.00 0 YES Muslim (OBC) 676542 Nediyapparambil House, 2 Kerala Malappuram 10-01-18 Akshay Dev V K Damodaran N P Nilambur Post, Malappuram- Male 17 3,500 TLM 12 - 18 1 6,140.00 0 6140.00 6,140.00 0 0 6,140.00 0 YES Muslim (OBC) 679329 Veluthedath House, Vadakkumpadam Post, 3 Kerala Malappuram 10-01-18 Akshaya K R Radhakrishnan Female 16 4000 TLM 12 - 18 1 6,140.00 0 6140.00 6,140.00 0 0 6,140.00 0 YES Muslim (OBC) Vandoor, Nilambur, Malappuram Panthalingal, Kaattumunda, Pallippad, Naduvath, 4 Kerala Malappuram 10-01-18 Aslah P Mustafa P Male 12 2,500 TLM 12 - 18 1 6,140.00 0 6140.00 6,140.00 0 0 6,140.00 0 YES Muslim (OBC) Mambad Village, Thiruvali, Malappuram-679328 Cheenkanniparackal, Kattmunda, Naduvath Post, Christian 5 Kerala Malappuram 10-01-18 Sneha Philipose Philipose Female 17 4000 TLM 12 - 18 1 6,140.00 0 6140.00 6,140.00 0 0 6,140.00 0 YES Vandoor Village, Thiruvali, General Malappuram-679328 Palakkodan, Chenakkulangara, Naduvath 6 Kerala Malappuram 10-01-18 Linju P Narayanan Female 14 1500 TLM 12 - 18 1 6,140.00 -

Assessment of Biodiversity Loss Along the Flood and Landslide-Hit Areas of Attappady Region, Palakkad District, Using Geoinformatics

ASSESSMENT OF BIODIVERSITY LOSS ALONG THE FLOOD AND LANDSLIDE-HIT AREAS OF ATTAPPADY REGION, PALAKKAD DISTRICT, USING GEOINFORMATICS Report submitted To Kerala State Biodiversity Board, Thiruvananthapuram. Submitted By Government College Chittur, Palakkad. Project summary Assessment of biodiversity loss along the flood and 1 Title landslide-hit areas of Attappady region, Palakkad district using geoinformatics. Kerala State Biodiversity Board 2 Project funded by L-14, Jai Nagar Medical College P.O. Thiruvananthapuram-695 011 3 Project period January 2019 – March 2019 Dr. Richard Scaria (Principal Investigator) Sojan Jose (Co-Investigator) Aswathy R. (Project Fellow - Zoology) Smitha P.V. (Project Fellow - Botany) Vincy V. (Project Fellow - Geography) 4 Project team Athulya C. (Technical Assistant - Zoology) Jency Joy (Technical Assistant - Botany) Ranjitha R. (Technical Assistant - Botany) Krishnakumari K. (Technical Assistant - Botany) Hrudya Krishnan K. (Technical Assistant - Botany) Identification of the geographical causes of flood and landslides in Attappady. Construction of maps of flood and landslide-hit areas and susceptible zones. Proposal of effective land use plans for the mitigation of flood and landslides. 5 Major outcomes Estimation of damages due to landslides and flood. Assessment of the biodiversity loss caused by flood and landslides. Diversity study of major floral and faunal categories. Post flood analysis of soil fertility variation in riparian zones. Prof. Anand Viswanath. R Dr. Richard Scaria Sojan Jose Principal, (Principal Investigator) (Co-Investigator) Govt. College, Chittur, Department of Geography, Department of Botany, Palakkad. Govt. College, Chittur, Govt. College, Chittur, Palakkad. Palakkad. 1. Introduction Biodiversity is the immense variety and richness of life on Earth which includes different animals, plants, microorganisms etc. -

Name of District : Palakkad Phone Numbers PS Contact LAC Name of Polling Station Name of BLO in Charge Designation Office Address NO

Palakad District BLO Name of District : Palakkad Phone Numbers PS Contact LAC Name of Polling Station Name of BLO in charge Designation Office address NO. Address office Residence Mobile Gokulam Thottazhiyam Basic School ,Kumbidi sreejith V.C.., Jr Health PHC Kumbidi 9947641618 49 1 (East) Inspector Gokulam Thottazhiyam Basic School sreejith V.C.., Jr Health PHC Kumbidi 9947641619 49 2 ,Kumbidi(West) Inspector Govt. Harigan welfare Lower Primary school Kala N.C. JPHN, PHC Kumbidi 9446411388 49 3 ,Puramathilsseri Govt.Lower Primary school ,Melazhiyam Satheesan HM GLPS Malamakkavu 2254104 49 4 District institution for Education and training Vasudevan Agri Asst Anakkara Krishi Bhavan 928890801 49 5 Aided juniour Basic school,Ummathoor Ameer LPSA AJBS Ummathur 9846010975 49 6 Govt.Lower Primary school ,Nayyur Karthikeyan V.E.O Anakkara 2253308 49 7 Govt.Basic Lower primary school,Koodallur Sujatha LPSA GBLS koodallur 49 8 Aided Juniour Basic school,Koodallur(West Part) Sheeja , JPHN P.H.C kumbidi 994611138 49 9 Govt.upper primary school ,Koodallur(West Part) Vijayalakshmi JPHN P.H.C Kumbidi 9946882369 49 10 Govt.upper primary school ,Koodallur(East Part) Vijayalakshmi JPHN P.H.C Kumbidi 9946882370 49 11 Govt.Lower Primary School,Malamakkavu(east Abdul Hameed LPSA GLPS Malamakkavu 49 12 part) Govt.Lower Primary School.Malamakkavu(west Abdul Hameed LPSA GLPS Malamakkavu 49 13 part) Moydeenkutty Memmorial Juniour basic Jayan Agri Asst Krishi bhavan 9846329807 49 14 School,Vellalur(southnorth building) Kuamaranellur Moydeenkutty Memmorial Juniour -

Theatre Criticism in Malayalam K

Theatre Criticism in Malayalam K. AYYA PPA PAN!KER 1. Theatre Tradition in Keroia heatre criticism in Kerala probably dates back to the comments On Meypadu in Tolkappiyam in the pan-Dravidian days, long before Malayalam evolved as a lan T guage (12th century). To what extent these were influenced by similar treatises like Bbarata' s Nii fJasastra is not clear. The continuity of the Kutiyauam presentationsof Sanskrit plays is some evidence of the early preoccupations of Keralites with dramaturgy. It is even argued that Abhinavagupta's Abhinavabhiirati is conceived in the form of answers to questions raised by theatre workers from Keral a who went to Kashmir to seek clarifications from the great savant. The attaprakarams (stage manuals) and kram adipikas (production manuals) of Kiiuyartam are an indica tion of self- awareness on the pan of actors and trainers pfactors. Theatre criticism is internalized in these manuals and the oral tradition of criticism must have contributed to the growth of this self- awareness. Perhaps the earliest of available texts on Kerala stage and theatre is Biilariimabharatam , an 18th cent ury treatise in Sanskrit writte n by Kartika TirunalBalararna Vanna Maharaja of Travancore. It is an attempt to describe ~e !ec~ue .s .pf stage presentation in the IOUry atrika style used in Kerala.,Tbough basically inspired by Bharata's Naryasjjstra, it con- . tains - many concepts deviating from the original. One of the .imporrant ideas in . BiiJaramabha~atam c0llf'em s the defmitiofl,£l"JJ'!"!"'t~~.; . " v, . ) , • _ ~ - _ .:" _ .: ~ , .L. i fO ' 41' i - ' yr .: :; · ~ t'...~ "", ~__ ' ''' ~- - ~ 2. The Definition ofBbarata:t 'am ..c· t. -

Govtorder 1 1594726095.Pdf

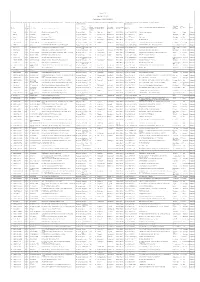

Width Width Name of of Road Length of Name of Panchayath/M Name of Road, Bridge, Culvert, (in m) Sl No District of Road Carriag Amount Constituency uncipality/Cor Building RoW=Ri (in km) e way poration ght of (in m) Way 1 Malappuram Vengara A R Nagar മാളിൽ മാറാപ്പിൽ ററാ蕍 1 3 3 1000000 ക ാളപ്പുറം 2 Malappuram Vengara A R Nagar ുറ്റൂർ ാരപറമ്പ് ററാ蕍 1 3 3 1000000 സാന്ത്വനം ററാ蕍 മമ്പുറം 3 Malappuram Vengara A R Nagar കെട്ടത്ത്ബസാർ 1 3 3 1000000 റ ാൺ啍 ീറ്റിം嵍 Muthuvara Churakkattukara 4 Thrissur Vadakkanchery Adatt 2.5 3 3 2500000 Ottucompany Jn ക ാച്ചു ുട ൽ- 5 Idukki റേെി ുളം Adimaly 3 3 3 12500000 െലിയ ുട ൽ ററാ蕍 6 Idukki റേെി ുളം Adimaly ാറെരി നടപ്പാലം 1.5 3 3 1500000 തുമ്പിപ്പാറ-അടക്കാ ുളം 7 Idukki റേെി ുളം Adimaly 12 3 3 2500000 ററാ蕍 8 Ernakulam Kunnathunadu Aikkaranadu Asramam kaval-GRK road 1.5 3 3 1500000 9 Ernakulam Kunnathunadu Aikkaranadu Vennikkulam colony road 1 3 3 1000000 Nambyarumpady-Karukappilly-Leksham 10 Ernakulam Kunnathunadu Aikkaranadu 2 3 3 2000000 veedu Colony road RoW greater Aikarassali-Koduvathra- than 11 Kottayam Eattumanoor Aimanam 0.75 3 2250000 Pookalathusali Road 3.0m & less than 5.5m RoW greater than 12 Kottayam Eattumanoor Aimanam Kaithakam St.George Road 0.4 3 1200000 3.0m & less than 5.5m RoW greater Olassas Charthali Road & than 13 Kottayam Eattumanoor Aimanam Kreemadam school Vadyanmekkari 1.3 3 1317250 3.0m & road less than 5.5m RoW greater than 14 Kottayam Eattumanoor Aimanam Kollathukari - Kareemadam 0.9 3 1080000 3.0m & less than 5.5m RoW greater than 15 Kottayam Eattumanoor Aimanam Madaserry- Maniyaparambu -

Form 19 a (See Rule 24 A(3)) Certified List ( GROUP B- PART-I) It

Form 19 A (See Rule 24 A(3)) Certified List ( GROUP B- PART-I) It is certified that the persons whose names are appering in this list are tested as positve as on 12/12/2020 15:32:10 (Date & Time) for covid 19 infection by the Government Hospital/Lab recognized by the Government OR are under quarantine due to COVID 19 ELECTION DETAILS ID CARD DETAILS Gender GP/ Municpality / Name of Ward Sl Municipal / Ward Name of Block Name of Dist Electoral roll Part Name of Address of the present location of hospitalisation/ quarantine Grama Taluk District Name Age Father/ Husband Address for communication with Pincode District GP/Municipal / No No No /M / F Corporation No Divsion & No Divsion & No no Sl no ID card panchayath Corporation /T serial No 1 Amina 61 M S/o W/o Saidali Chorath Valappil thalamunda, 679576 Malappuram Edapal G94 9 Thuyyam/9 Edappal/12 Pt.No2 SlNo563 Election KL/06/038/534095 Chorath Valappil thalamunda Edapal 9 Ponnani Malappuram Id 2 Rasheed 38 M S/o Saidalavi Palliyalil, 676108 Malappuram Triprangode G88 9 Chamravattom/10 Thirunavaya/16 Pt.No1 SlNo205 Election FMJ1817931 Palliyalil Triprangode 9 Tirur Malappuram Id 3 Shahid 28 M S/o Hidayathulla Padinjarakath, 676108 Malappuram Triprangode G88 18 Alathiyur/9 Thirunavaya/16 Pt.No1 SlNo888 Election YEU0460931 Padinjarakath Triprangode 18 Tirur Malappuram Id 4 abilash 26 M S/o rajagobalan EDATHARATHODI, 679357 Malappuram Aliparamba G43 18 Kunnakkavu/10 Elamkulam/6 Pt.No2 SlNo181 Election fqj3647963 EDATHARATHODI Aliparamba 18 PerinthalmannaMalappuram Id 5 ANJU CHALARI 27 F S/o RAVEENDRAN CHALARI KANNAMVETTIKKAVU, 673637 Malappuram Cherukavu G08 4 Puthukkode/17 Vazhakkad/28 Pt.No1 SlNo61 Election ZXU0350728 CHALARI KANNAMVETTIKAVU CHERAPADAM Cherukavu 4 Kondotty Malappuram Id 6 FAISAL K 38 M S/o koya KARIMBANAKKAL,NAITHALLOOR,PONNANI, 679584 Malappuram Ponnani Wards 1 M42 12 / / Pt.No02 SlNo835 Election SECIDCB81A85C KARIMBANAKKAL,NAITHALLOOR,PONNANI Ponnani Wards 1 12 Ponnani Malappuram to 26 Id to 26 7 Hafeefa. -

Accused Persons Arrested in Malappuram District from 03.05.2020To09.05.2020

Accused Persons arrested in Malappuram district from 03.05.2020to09.05.2020 Name of Name of the Name of Place at Date & Arresting Court at Sl. Name of the the father Age & Address of Cr. No & Sec Police which Time of Officer, which No. Accused of Sex Accused of Law Station Arrested Arrest Rank & accused Accused Designation produced 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 274/2020 U/s ANTHUR 143, 145, 147, HARIS VALAPPIL 08-05- 188, 269, SANGEETH, SI ABDUL 28, KUNNUMMA MALAPPUR BAILED BY 1 MUHAMME HOUSE, 2020 AT 270, 34 IPC, MALAPPURA MAJEED MALE L AM POLICE D MUTHUR P.O, 11:05 HRS 118(e) KP Act M PS EDAPPAL & 4(2)(a), 5 of KEDO 274/2020 U/s KILIYANKUNNA 143, 145, 147, TH HOUSE 08-05- 188, 269, SANGEETH, SI ABDUL ABDUL 25, ALAMKODE PO KUNNUMMA MALAPPUR BAILED BY 2 2020 AT 270, 34 IPC, MALAPPURA HAKKEEM HAMEED MALE PERUMUKKU L AM POLICE 11:05 HRS 118(e) KP Act M PS CHANGARAMK & 4(2)(a), 5 ULAM of KEDO 274/2020 U/s ERIKKUNNAN 143, 145, 147, HOUSE, 08-05- 188, 269, SANGEETH, SI ABDUL 25, KUNNUMMA MALAPPUR BAILED BY 3 ANSHID PATTARKULAM, 2020 AT 270, 34 IPC, MALAPPURA SALAM MALE L AM POLICE NARUKKARA, 11:05 HRS 118(e) KP Act M PS MANJERI & 4(2)(a), 5 of KEDO 274/2020 U/s MOOCHIKKAD 143, 145, 147, AN HOUSE, 08-05- 188, 269, SANGEETH, SI 21, KUNNUMMA MALAPPUR BAILED BY 4 JASEEL YOUSUF OTHUKKUNGA 2020 AT 270, 34 IPC, MALAPPURA MALE L AM POLICE L, 11:05 HRS 118(e) KP Act M PS MALAPPURAM & 4(2)(a), 5 of KEDO 273/2020 U/s 143, 145, 147, PRASADAM 188, 269, 270 A. -

Tribal Sub-Plan (TSP)

Public Disclosure Authorized Public Disclosure Authorized Public Disclosure Authorized Public Disclosure Authorized SFG3366 Tamil Nadu Rural Transformation Project Tribal Development Plan Final Report April 2017 Abbreviations APO Annual Plan Outlay BPL Below Poverty Line CPIAL Consumer Price Index for Agricultural Labourers DIC District Industries Centre DPH Department of Public Health DPMU District Programme Management Unit (National Urban Health Mission) DTE Directorate of Technical Education FRA Forest Rights Act GDI Gender Development Index GDP Gross Domestic Product GTR Government Tribal Residential (School) HDI Human Development Index HH Household ICDS Integrated Child development Services Scheme ICT Information Communication Technology INR Indian Rupee Km Kilometres KVIC Khadi and Village Industries Commission LPG Liquefied Petroleum Gas MGNREGA Mahatma Gandhi National Rural Employment Guarantee Act MMU Mobile Medical Unit MSME Micro, Small and Medium Enterprises NABARD National Bank for Agriculture and Rural Development NAC National Advisory Council NAP National Afforestation Programme NGO Non-Governmental Organisation NID National Institute of Design NIFT National Institute of Fashion Technology NRLM National Rural Livelihood Mission NRLP National Rural Livelihood Project NTFP Non-Timber Forest Produce OP Operational Policy PCR Protection of Civil Rights PDO Project Development Objective PESA Panchayat Act Extension to Tribal Areas PHC Primary Health Centre PIP Participatory Identification of Poor Scheduled Caste and scheduled -

Unclaimed Deposits Transferred to RBI During Aug 2020

Unclaimed Deposits Transferred to RBI During Aug 2020 AC_NAME AC_NAME2 AC_ADDR1 AC_ADDR2 AC_ADDR3 ANIL KUMAR M P MARIKKAL HOUSE KALLOOR P O ANNAMANADA NOBY XAVIER S/O XAVIER 193/1 KOOTALAPARAMBIL ,NEAR CHAPEL BHARGAVAN E V THAYYATH HOUSE VANKULATHVAYAL AZHIKODE MARIAMMA P V W/O PAUL K L KAITHARATH HOUSE VETTUKADAVU RD CHALAKUDY CHERU P T PAVNAN HOUSE P O CHALISSERY JOHN G LOBO PUTHENPARAMBIL HOUSE CHANGANACHERY VARGHESE T G THEKKEPUTHENPURAKKAL MADAPPALLY P.O. VENKOTTA, CHANGANASERRY AKBAR K K . 4/144 KSHEMA BAVA RD KARIPALAM VOTERS ID ADDRESS- 4/245 MARTIN SEBASTIAN MATTAMMAL HOUSE BMC PO ERNAKULAM BHUPAL U K P 102,ABIRAMI APPARTMENT KUMILANKUTTAI,KCP THOTTAM ERODE 638011 RATHNA SUNDER SUNDER COTTAGE 4/16A UPPER GUDALLUR NILGIRIS NARAYANAN M MAILAKODATHU HOUSE KADAPPURAM CHAVAKKAD JANAKIAMMA PARAMESWARAN PILLAI PANTHAPLAVIL VADAKKATHIL BHARANIKKAVU S PALLICKAL P O KALA PRADEEP PERRUVALLY THEKKATHIL KANNAMPILLY BHAGOM KAYAMKULAM BINU VARGHESE KOCHADATHIL HOUSE KEERAMPARA NAJUMUDEEN H PANDARATHUMVILA PUTHEN VEEDU KALLUMTHAZHAM P O KILIKOLLUR KOLLAM ARUNPRAKASH E S/O.P ELANGOVAN 3/92,NATHAMEDU KODUMUDI B KOKILAMBAL 66/34,EAST AGRAHARAM KODUMUDI ERODE DT ABDUL NAZAR E N XI/313, AISWARYA COLONY PUDUNAGARAM P.O. ANWAR M H S/O HAMEED MALIAKKAL HOUSE THOZIYOOR PRADEEP KUMAR.V VADAKKAYIL HOUSE O.K.ROAD THIRUVANNUR ASHARAF K A S/O ABDULRAHIMAN KULANGARA VEETTIL VELLARAKKAD P O NISHA V R VADASSEERY HOUSE, KANIPPAYYOOR P O KUNNAMKULAM GEETHA A A CHETTIKATTIL HOUSE P O ARIMPOOR M.JEEVAN BABU,ANUSHA 10/16 KULANDAI GRAMANI STREET CHENNAI ALIYAMMA THOMAS