Dixie's Last Stand

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The View from Ventress News from the College of Liberal Arts | Libarts.Olemiss.Edu

University of Mississippi eGrove Liberal Arts Newsletters Liberal Arts, College of 2019 The iewV from Ventress - 2019 University of Mississippi. College of Liberal Arts Follow this and additional works at: https://egrove.olemiss.edu/libarts_news Part of the Arts and Humanities Commons, Life Sciences Commons, Physical Sciences and Mathematics Commons, and the Social and Behavioral Sciences Commons Recommended Citation University of Mississippi. College of Liberal Arts, "The ieV w from Ventress - 2019" (2019). Liberal Arts Newsletters. 10. https://egrove.olemiss.edu/libarts_news/10 This Book is brought to you for free and open access by the Liberal Arts, College of at eGrove. It has been accepted for inclusion in Liberal Arts Newsletters by an authorized administrator of eGrove. For more information, please contact [email protected]. 2018–19 Academic Year The University of Mississippi The View from Ventress News from the College of Liberal Arts | libarts.olemiss.edu Arabic Language Flagship “Here in Oxford, at the University of Mississippi, is one of the best Arabic programs in the country.” —JOHN CHAPPELL Rhodes Scholar finalist and Arabic Flagship graduate John Chappell (BA international studies n 2018 the Department of Modern Languages was learners with the ambition and determination to make and Arabic ’19) photographed fellow awarded an Arabic Flagship Program, sponsored by the positive changes in all sectors—public and private—through students riding in a caravan on the Erg National Security Education Program, a federal a well-grounded, balanced view of the Arab region.” Chebbi Dunes of Tafilalet, Morocco. I initiative to create a wider and better-qualified pool of US The Flagship provides funds to hire new faculty, add citizens with foreign language and international skills. -

Oxford, Mississippi

Pick up a copy of our Walking Tour Guide” and take a stroll through Oxford’s historic neighborhoods. xford, Mississippi was incorporated in May of 1837, the lives of Oxford residents, as well as University students, such Welcomeand was built on land that had onceto belonged Oxford, as Mississippi... the University Greys, a group of students decimated at the to the Chickasaw Indian Nation. The town was Battle of Gettysburg. established on fifty acres, which had been conveyed During the Civil Rights movement, Oxford again found itself in the Oto the county by three men, John Chisholm, John J. middle of turmoil. In 1962, James Meredith entered the University Craig and John D. Martin. The men had purchased the land from of Mississippi as the first African American student. two Chickasaw Indians, HoKa and E Ah Nah Yea. Since that time, Oxford has thrived. The city is now known as the Lafayette County was one of 13 counties that had been created home of Nobel Prize winning author William Faulkner and has in February of 1836 by the state legislature. Most of the counties been featured as a literary destination in publications such as were given Chickasaw names, but Lafayette was named for Conde Nast Traveler, Southern Living and Garden and Gun. Many Marquis de Lafayette, the young French aristocrat who fought writers have followed in Faulkner’s footsteps, making Oxford alongside the Americans during the Revolutionary War. their home over the years and adding to Oxford’s reputation as a The Mississippi Legislature voted in 1841 to make Oxford the literary destination. -

November 02, 2010

University of Mississippi eGrove Daily Mississippian Journalism and New Media, School of 11-2-2010 November 02, 2010 The Daily Mississippian Follow this and additional works at: https://egrove.olemiss.edu/thedmonline Recommended Citation The Daily Mississippian, "November 02, 2010" (2010). Daily Mississippian. 608. https://egrove.olemiss.edu/thedmonline/608 This Newspaper is brought to you for free and open access by the Journalism and New Media, School of at eGrove. It has been accepted for inclusion in Daily Mississippian by an authorized administrator of eGrove. For more information, please contact [email protected]. 1 T UESDAY , NOVEMBER 2, 2010 | VOL . 99, NO . 50 THE DAILY homecoming week MISSISSIPPIAN TODAY T HE ST UDEN T NEW S PAPER OF THE UNIVER S I T Y OF MI ss I ss IPPI | SERVING OLE MI ss AND OXFORD S INCE 1911 | WWW . T HED M ONLINE . CO M 92.1 REBEL RADIO LIVE REMOTE UM’s own Rebel Radio will host a live remote in front of the Student Going to new heights for charity Union from 11 a.m. until 1 p.m. PIZZA WALK doned children while the Mis- tance from they live. The Staff Council will host a Pizza sissippi Department of Human “One of the students asked Walk from 11 a.m. until 1 p.m. in Services investigates their home me if I would teach them, so I the Student Union Plaza. situation or arranges a foster got to teach for about 30 min- home. Carr asked for people to utes– and they were some very, SPB HOMECOMING make pledges to Angel Ranch very intelligent kids,” she said. -

Center for Public History

Volume 8 • Number 2 • spriNg 2011 CENTER FOR PUBLIC HISTORY Oil and the Soul of Houston ast fall the Jung Center They measured success not in oil wells discovered, but in L sponsored a series of lectures the dignity of jobs well done, the strength of their families, and called “Energy and the Soul of the high school and even college graduations of their children. Houston.” My friend Beth Rob- They did not, of course, create philanthropic foundations, but ertson persuaded me that I had they did support their churches, unions, fraternal organiza- tions, and above all, their local schools. They contributed their something to say about energy, if own time and energies to the sort of things that built sturdy not Houston’s soul. We agreed to communities. As a boy, the ones that mattered most to me share the stage. were the great youth-league baseball fields our dads built and She reflected on the life of maintained. With their sweat they changed vacant lots into her grandfather, the wildcatter fields of dreams, where they coached us in the nuances of a Hugh Roy Cullen. I followed with thoughts about the life game they loved and in the work ethic needed later in life to of my father, petrochemical plant worker Woodrow Wilson move a step beyond the refineries. Pratt. Together we speculated on how our region’s soul—or My family was part of the mass migration to the facto- at least its spirit—had been shaped by its famous wildcat- ries on the Gulf Coast from East Texas, South Louisiana, ters’ quest for oil and the quest for upward mobility by the the Valley, northern Mexico, and other places too numerous hundreds of thousands of anonymous workers who migrat- to name. -

LYCEUM-THE CIRCLE HISTORIC DISTRICT Page 1 United States Department of the Interior, National Park Service National Register of Historic Places Registration Form

NATIONAL HISTORIC LANDMARK NOMINATION NPS Form 10-900 USDI/NPS NRHP Registration Form (Rev. 8-86) OMB No. 1024-0018 LYCEUM-THE CIRCLE HISTORIC DISTRICT Page 1 United States Department of the Interior, National Park Service National Register of Historic Places Registration Form 1. NAME OF PROPERTY Historic Name: Lyceum-The Circle Historic District Other Name/Site Number: 2. LOCATION Street & Number: University Circle Not for publication: City/Town: Oxford Vicinity: State: Mississippi County: Lafayette Code: 071 Zip Code: 38655 3. CLASSIFICATION Ownership of Property Category of Property Private: Building(s): ___ Public-Local: District: X Public-State: X Site: ___ Public-Federal: Structure: ___ Object: ___ Number of Resources within Property Contributing Noncontributing 8 buildings buildings 1 sites sites 1 structures structures 2 objects objects 12 Total Total Number of Contributing Resources Previously Listed in the National Register: ___ Name of Related Multiple Property Listing: NPS Form 10-900 USDI/NPS NRHP Registration Form (Rev. 8-86) OMB No. 1024-0018 LYCEUM-THE CIRCLE HISTORIC DISTRICT Page 2 United States Department of the Interior, National Park Service National Register of Historic Places Registration Form 4. STATE/FEDERAL AGENCY CERTIFICATION As the designated authority under the National Historic Preservation Act of 1966, as amended, I hereby certify that this ____ nomination ____ request for determination of eligibility meets the documentation standards for registering properties in the National Register of Historic Places and meets the procedural and professional requirements set forth in 36 CFR Part 60. In my opinion, the property ____ meets ____ does not meet the National Register Criteria. -

Georgia Vs Clemson (9/26/1970)

Clemson University TigerPrints Football Programs Programs 1970 Georgia vs Clemson (9/26/1970) Clemson University Follow this and additional works at: https://tigerprints.clemson.edu/fball_prgms Materials in this collection may be protected by copyright law (Title 17, U.S. code). Use of these materials beyond the exceptions provided for in the Fair Use and Educational Use clauses of the U.S. Copyright Law may violate federal law. For additional rights information, please contact Kirstin O'Keefe (kokeefe [at] clemson [dot] edu) For additional information about the collections, please contact the Special Collections and Archives by phone at 864.656.3031 or via email at cuscl [at] clemson [dot] edu Recommended Citation University, Clemson, "Georgia vs Clemson (9/26/1970)" (1970). Football Programs. 89. https://tigerprints.clemson.edu/fball_prgms/89 This Book is brought to you for free and open access by the Programs at TigerPrints. It has been accepted for inclusion in Football Programs by an authorized administrator of TigerPrints. For more information, please contact [email protected]. "1 vs Clemson ATHENS, GA./SANFORD STADIUM / SEPTEMBER 26, 1970/ONE DOLLAR The name is POSS. right here in Athens, makes such famous POSS delicacies as Brunswick Stew, Pork with Barbecue whats Sauce, Sloppy Joes, Bottled Hot Sauce, Hot Dog It's synonomous with traditional Southern eating Chili and Chili with Beans. — just as Sanford Stadium means exciting football. in a What's in our name? A lot of famous good eat- It arouses visions of succulent steaks, tender bar- . of Southern tradition. becue and mouth-watering Brunswick Stew. ing more than 40 years Enjoy POSS' famous foods . -

Tcu-Smu Series

FROG HISTORY 2008 TCU FOOTBALL TCU FOOTBALL THROUGH THE AGES 4General TCU is ready to embark upon its 112th year of Horned Frog football. Through all the years, with the ex cep tion of 1900, Purple ballclubs have com pet ed on an or ga nized basis. Even during the war years, as well as through the Great Depres sion, each fall Horned Frog football squads have done bat tle on the gridiron each fall. 4BEGINNINGS The newfangled game of foot ball, created in the East, made a quiet and un offcial ap pear ance on the TCU campus (AddRan College as it was then known and lo cat ed in Waco, Tex as, or nearby Thorp Spring) in the fall of 1896. It was then that sev er al of the col lege’s more ro bust stu dents, along with the en thu si as tic sup port of a cou ple of young “profs,” Addison Clark, Jr., and A.C. Easley, band ed to gether to form a team. Three games were ac tu al ly played that season ... all af ter Thanks giv ing. The first con test was an 86 vic to ry over Toby’s Busi ness College of Waco and the other two games were with the Houston Heavy weights, a town team. By 1897 the new sport had progressed and AddRan enlisted its first coach, Joe J. Field, to direct the team. Field’s ballclub won three games that autumn, including a first victory over Texas A&M. The only loss was to the Univer si ty of Tex as, 1810. -

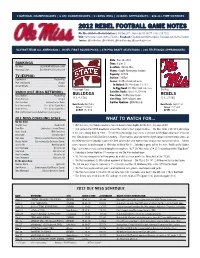

2012 Rebel Football Game Notes

3 NATIONAL CHAMPIONSHIPS | 6 SEC CHAMPIONSHIPS | 21 BOWL WINS | 33 BOWL APPEARANCES | 626 ALL-TIME VICTORIES 22012012 RREBELEBEL FFOOTBALLOOTBALL GGAMEAME NNOTESOTES Ole Miss Athletics Media Relations | PO Box 217 | University, MS 38677 | 662-915-7522 Web: OleMissSports.com, OleMissFB.com | Facebook: Facebook.com/OleMissSports, Facebook.com/OleMissFootball Twitter: @OleMissNow, @OleMissFB, @RebelGameday, @CoachHughFreeze 54 FIRST-TEAM ALL AMERICANS | 19 NFL FIRST ROUND PICKS | 279 PRO DRAFT SELECTIONS | 216 TELEVISION APPEARANCES Date: Nov. 24, 2012 RANKINGS Time: 6 p.m. CT Ole Miss . BCS-NR/AP-NR/Coaches-NR Location: Oxford, Miss. Mississippi State . .BCS-NR/AP-t25/Coaches-24 Venue: Vaught-Hemingway Stadium Capacity: 60,580 TV (ESPNU) Surface: FieldTurf Clay Matvick . Play-by-Play Series: Ole Miss leads 60-42-6 Matt Stinchcomb . Analyst Allison Williams . Sideline In Oxford: Ole Miss leads 21-11-3 Mississippi State In Egg Bowl: Ole Miss leads 54-25-5 Ole Miss RADIO (OLE MISS NETWORK) BULLDOGS Satellite Radio: Sirius 94, XM 198 REBELS David Kellum . Play-by-Play Live Stats: OleMissSports.com Harry Harrison . Analyst (8-3, 4-3 SEC) Live Blog: OleMissSports.com (5-6, 2-5 SEC) Stan Sandroni . Sideline/Locker Room Twitter Updates: @OleMissFB Head Coach: Dan Mullen Head Coach: Hugh Freeze Brett Norsworthy . Pre- & Post-Game Host Career: 29-20/4th Career: 35-13/4th Richard Cross . Pre- & Post-Game Host At MSU: 29-20/4th At UM: 5-6/1st Web: OleMissSports.com RebelVision (subscription) OLE MISS COACHING STAFF WHAT TO WATCH FOR... On the field: Hugh Freeze . Head Coach • With five wins, the Rebels need one more to become bowl eligible for the first time since 2009. -

Virginia Vs Clemson (10/8/1960)

Clemson University TigerPrints Football Programs Programs 1960 Virginia vs Clemson (10/8/1960) Clemson University Follow this and additional works at: https://tigerprints.clemson.edu/fball_prgms Materials in this collection may be protected by copyright law (Title 17, U.S. code). Use of these materials beyond the exceptions provided for in the Fair Use and Educational Use clauses of the U.S. Copyright Law may violate federal law. For additional rights information, please contact Kirstin O'Keefe (kokeefe [at] clemson [dot] edu) For additional information about the collections, please contact the Special Collections and Archives by phone at 864.656.3031 or via email at cuscl [at] clemson [dot] edu Recommended Citation University, Clemson, "Virginia vs Clemson (10/8/1960)" (1960). Football Programs. 48. https://tigerprints.clemson.edu/fball_prgms/48 This Book is brought to you for free and open access by the Programs at TigerPrints. It has been accepted for inclusion in Football Programs by an authorized administrator of TigerPrints. For more information, please contact [email protected]. CLEMSON VIRGINIA CLEMSONJ — NEW DORMITORIES another sign of Clemson on the move These modern dormitories and many of the other buildings add much needed space for the growing Clemson Student Body. Kline Iron & Steel Company is pleased to have furnished the structural steel proud to have a part in Clemson's vital growth. KLINE IRON & STEEL CO. Plain and Fabricated Structural Steel and Metal Products for Buildings ANYTHING METAL 1225-35 Huger Street Columbio, S.C. Phone 4-0301 HART because they care how it fits and how it looks . SCHAFFNER everyone comes to . -

School of Law Catalog the UNIVERSITY of MISSISSIPPI Bulletin of the University of Mississippi P.O

2009-10 School of Law Catalog THE UNIVERSITY OF MISSISSIPPI Bulletin of The University of Mississippi P.O. Box 1848 2009-10 University, MS 38677-1848 Telephone (662) 915-6910 SCHOOL OF LAW www.olemiss.edu CATALOG A GREAT AMERICAN PUBLIC UNIVERSITY BULLETIN OF THE UNIVERSITY OF MISSISSIPPI Board of Trustees of State Institutions of Higher Learning By CONSTITUTIONAL AMENDMENT, the government of The University of Mississippi and of the other institutions of higher learning of the state of Mississippi is vested in a Board of Trustees appointed by the governor with the advice and consent of the Senate. After January 1, 2004, as vacancies occur, the 12-member Board of Trustees of State Institutions of Higher Learning shall be appointed from each of the three Mississippi Supreme Court districts, until there are four members from each Supreme Court district. The terms are staggered so that all members appointed after 2012 will have a term of nine years. The Board of Trustees selects one of its members as president of the board and appoints the chancellor as executive head of the university. The board maintains offices at 3825 Ridgewood Road, Jackson, MS 39205. Members whose terms expire May 7, 2018: CHRISTY PICKERING, Biloxi, SOUTHERN SUPREME COURT DISTRICT ALAN W. PERRY, Jackson, CENTRAL SUPREME COURT DISTRICT DOUGLAS W. ROUSE, Hattiesburg, SOUTHERN SUPREME COURT DISTRICT C.D. SMITH, JR., Meridian, CENTRAL SUPREME COURT DISTRICT Members whose terms expire May 7, 2015: ED BLAKESLEE, Gulfport, SOUTHERN SUPREME COURT DISTRICT BOB OWENS, Jackson, CENTRAL SUPREME COURT DISTRICT AUBREY PATTERSON, Tupelo, NORTHERN SUPREME COURT DISTRICT ROBIN ROBINSON, Laurel, SOUTHERN SUPREME COURT DISTRICT Members whose terms expire May 7, 2012: L. -

Meet Me at the Flagpole: Thoughts About Houston’S Legacy of Obscurity and Silence in the Fight of Segregation and Civil Right Struggles

Meet Me at the Flagpole: Thoughts about Houston’s Legacy of Obscurity and Silence in the fight of Segregation and Civil Right Struggles Bernardo Pohl Abstract This article focuses on the segregated history and civil right movement of Houston, using it as a case study to explore more meaningfully the teaching of this particular chapter in American history. I have a dream that one day every valley shall be exalted, every hill and mountain shall be made low, the rough places will be made straight and the glory of the Lord shall be revealed and all flesh shall see it together. Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. I remember the day very clearly. It was an evening at Cullen Auditorium at Uni- versity of Houston. It was during the fall of 2002, and it was the end of my student teach- ing. Engulfed in sadness, I sat alone and away from my friends. For me, it was the end of an awesome semester of unforgettable moments and the start of my new teaching career. I was not really aware of the surroundings; I did not have a clue about what I was about to experience. After all, I just said yes and agreed to another invitation made by Dr. Cam- eron White, my mentor and professor. I did not have any idea about the play or the story that it was about to start. The word “Camp Logan” did not evoke any sense of familiarity in me; it did not resonate in my memory. Besides, my mind was somewhere else: it was in the classroom that I left that morning; it was in the goodbye party that my students prepared for me; and it was in the uncertain future that was ahead of me. -

October 9, 2017

University of Mississippi eGrove Daily Mississippian Journalism and New Media, School of 10-9-2017 October 9, 2017 The Daily Mississippian Follow this and additional works at: https://egrove.olemiss.edu/thedmonline Recommended Citation The Daily Mississippian, "October 9, 2017" (2017). Daily Mississippian. 206. https://egrove.olemiss.edu/thedmonline/206 This Newspaper is brought to you for free and open access by the Journalism and New Media, School of at eGrove. It has been accepted for inclusion in Daily Mississippian by an authorized administrator of eGrove. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Monday, October 9, 2017 THE DAILY Volume 106, No. 28 MISSISSIPPIANTHE STUDENT NEWSPAPER OF THE UNIVERSITY OF MISSISSIPPI SERVING OLE MISS AND OXFORD SINCE 1911 Visit theDMonline.com @thedm_news Chancellor announces plan for offi cial mascot switch SLADE RAND with the Landshark as the after more than 4,100 stu- with executive committees decisions — in the interest of MANAGING EDITOR offi cial mascot and retire dents voted in an Associated of alumni, faculty, staff and what is best for the future of Rebel the Bear,” Vitter said Student Body-sponsored poll graduate student groups to our university and our stu- in a statement Friday. Vitter gauging student support for help fi nalize their decision. dents. We are focused upon Ole Miss fans will have a said Friday’s announcement the Landshark. Less than 20 “After we received positive moving forward with a mas- new mascot to cheer with served to offi cially retire Reb- percent of all students en- support and endorsements cot that unifi es and inspires, along the sidelines when the el the Black Bear.