“Damned If You Do and Damned If You Don't: the Hegemony Of

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Muscled Movie Mavens: a New Need for the Fernale Form in Pumpinp: Iran II, Tenninator 2, and G.1 Tane

Muscled Movie Mavens: A New Need for the Fernale Form in Pumpinp: Iran II, Tenninator 2, and G.1 Tane A thesis submitted to the Faculty of Graduate Studies in partial fulfillment of the requirernents for the degree of Masters of Fine Arts Graduate Programme in Film and Video York University North York, Ontario August 2000 National Library Bibliothèque nationale u+1 ,,,a du Canada Acquisitions and Acquisitions et Bibliographic Services services bibliographiques 395 Wellington Street 395, rue Wellington Ottawa ON KiA ON4 Ottawa ON KIA ON4 Canada Canada The author has granted a non- L'auteur a accordé une licence non exclusive licence allowing the exclusive permettant à la National Library of Canada to Bibliothèque nationale du Canada de reproduce, loan, distri'bute or sell reproduire, prêter, distribuer ou copies of this thesis in microform, vendre des copies de cette thèse sous paper or electronic formats. la forme de microfichelnlm, de reproduction sur papier ou sur format électronique. The author retains ownership of the L'auteur conserve la propriété du copyright in this thesis. Neither the droit d'auteur qui protège cette thèse. thesis nor substantial extracts fiom it Ni la thèse ni des extraits substantieIs may be printed or otherwise de celle-ci ne doivent être imprimés reproduced without the author's ou autrement reproduits sans son permission. autorisation. MuscIed Movie Mavens: A New Need for the Female Form in Pumpine Iron II, Tenninator 2, and G.I. Jane by Petra E. Janopaul a thesis submitted to the Faculty of Graduate Studies of York University in partial fuifillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Fine Arts Permission has been granted to the LIBRARY OF YORK UNIVERSITY to tend or seIl copies of this thesis. -

FEMALE BODYBUILDING and GENDER CONSTRUCTION, in Media Information Australia, No.75, February, 1995, Pp.13-23

1 Angela Ndalianis, MUSCLE, EXCESS AND RUPTURE: FEMALE BODYBUILDING AND GENDER CONSTRUCTION, in Media Information Australia, no.75, February, 1995, pp.13-23. (ISSN 0312-9616). MAINSTREAMING `MONSTROUS MEAT' In recent years bodybuilding culture has provided the backdrop to a series of debates centering around issues surrounding representations of gender and in particular the potential inherent in bodybuilding bodies to rupture preconceived notions regarding `norms' of masculinity and femininity; for the meticulously controlled, predetermined construction and definition of mass and muscle on the bodybuilding figure has shifted the body from an arena dominated by assumptions centering around the natural to a sphere which exposes the body itself - and with it the power structures that impose meaning onto it - as informed by culture. The bodybuilding physique reveals the body as a socially determined construct, or to cite Kuhn, with the willed construction of bodies in bodybuilding, `nature becomes culture'. (Kuhn 1988, 5) The question of marketability has, over the years, emerged as a key concern in bodybuilding. Of all sports, due to its tendency towards things excessive, bodybuilding tends to stand outside the mainstream appealing primarily to a select, cult following. There have been some exceptions of bodybuilders who successfully escaped the margins and entered mainstream culture, the most successful being Arnold Schwarzenegger (seven time Mr.Olympia) who opened the doors to big-time muscle in action cinema. More recently, female muscle has also started to make itself felt in the popular sphere, with Cory Everson ( six time winner of the Ms. Olympia) appearing in films such as Double Impact alongside Jean Claude van Damme, and professional bodybuilders Raye Hollitt, Shelley Beattie and Tonya Knight starring in the successful U.S. -

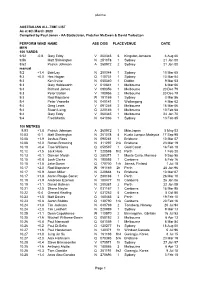

AA Statistician, Fletcher Mcewen & David

all-time AUSTRALIAN ALL-TIME LIST As at 6th March 2020 Compiled by Paul Jenes - AA Statistician, Fletcher McEwen & David Tarbotton PERFORM WIND NAME ASS DOB PLACEVENUE DATE MEN 100 YARDS 9.52 -0.8 Gary Eddy V 260345 5 Kingston,Jamaica 6 Aug 66 9.56 Matt Shirvington N 251078 1 Sydney 21 Jan 00 9.62 Patrick Johnson A 260972 2 Sydney 21 Jan 00 manual 9.2 +1.4 Bob Lay N 200344 1 Sydney 10 Mar 65 9.3 +0.0 Hec Hogan Q 110731 1 Sydney 13 Mar 54 9.3 Ken Irvine N 050340 1 Dubbo 9 Mar 63 9.3 Gary Holdsworth V 010841 1 Melbourne 6 Mar 66 9.3 Richard James V 090356 1 Melbourne 20 Dec 79 9.3 Peter Batten V 190956 2 Melbourne 20 Dec 79 9.3 Rod Mapstone W 191169 1 Sydney 3 Mar 86 9.4 Peter Vassella N 040141 1 Wollongong 4 Mar 62 9.4 Greg Lewis V 091246 2 Melbourne 16 Mar 66 9.4 Stuart Laing Q 220146 1 Melbourne 10 Feb 68 9.4 Gary Eddy V 260345 1 Melbourne 24 Jan 70 9.4 Fred Martin N 041066 1 Sydney 13 Feb 85 100 METRES 9.93 +1.8 Patrick Johnson A 260972 1 Mito,Japan 5 May 03 10.03 -0.1 Matt Shirvington N 251078 4 Kuala Lumpur,Malaysia 17 Sep 98 10.08 +1.9 Joshua Ross N 090281 1 Brisbane 10 Mar 07 10.08 +2.0 Rohan Browning N 311297 2rA Brisbane 23 Mar 19 10.10 +0.4 Trae Williams Q 050597 1 Gold Coast 16 Feb 18 10.12 +1.5 Jack Hale T 220598 1h2 Perth 1 Feb 20 10.13 +0.1 Damien Marsh Q 280371 1 Monte Carlo, Monaco 9 Sep 95 10.15 +0.8 Josh Clarke N 190595 1 Canberra 6 Feb 16 10.15 +1.5 Jake Doran Q 170700 1rA Jämsä, Finland 1 Jul 18 10.17 +2.0 Rod Mapstone W 191169 2h Perth 28 Jan 96 10.17 +0.9 Adam Miller N 220684 1s Brisbane 10 Mar 07 10.17 +1.8 Aaron -

Bodybuilding and Fitness Doping in Transition. Historical Transformations and Contemporary Challenges

social sciences $€ £ ¥ Article Bodybuilding and Fitness Doping in Transition. Historical Transformations and Contemporary Challenges Jesper Andreasson 1,* and Thomas Johansson 2 1 Department of Sport Science, Linnaeus University, 39182 Kalmar, Sweden 2 Department of Education, Learning and Communication, University of Gothenburg, 40530 Gothenburg, Sweden; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected] Received: 16 January 2019; Accepted: 27 February 2019; Published: 4 March 2019 Abstract: This article describes and analyses the historical development of gym and fitness culture in general and doping use in this context in particular. Theoretically, the paper utilises the concept of subculture and explores how a subcultural response can be used analytically in relation to processes of cultural normalisation as well as marginalisation. The focus is on historical and symbolic negotiations that have occurred over time, between perceived expressions of extreme body cultures and sociocultural transformations in society—with a perspective on fitness doping in public discourse. Several distinct phases in the history of fitness doping are identified. First, there is an introductory phase in the mid-1950s, in which there is an optimism connected to modernity and thoughts about scientifically-engineered bodies. Secondly, in the 1960s and 70s, a distinct bodybuilding subculture is developed, cultivating previously unseen muscular male bodies. Thirdly, there is a critical phase in the 1980s and 90s, where drugs gradually become morally objectionable. The fourth phase, the fitness revolution, can be seen as a transformational phase in gym culture. The massive bodybuilding body is replaced with the well-defined and moderately muscular fitness body, but at the same time there are strong commercialised values which contribute to the development of a new doping market. -

Steve Wennerstrom Papers Finding

T h e Steve Wennerstrom Papers The H.J. Lutcher Stark Center for Physical Culture & Sports The University of Texas at Austin Finding Aid Steve Wennerstrom Papers: 77 Boxes, 2 Oversized Boxes: 2833 Folders, 17 Artifacts, 130 Videos, no date, 1836-2014 (11491 items) Abstract Steve Wennerstrom is an expert on the history of women’s bodybuilding. He has served as the International Federation of Bodybuilders (IFBB) Women’s Historian. However, his interest in women’s sports extends beyond bodybuilding and the collection reflects that reality. Almost every sport that women have played is represented, making the Steve Wennerstrom Papers an invaluable resource to all researchers with an interest in women’s sports. Wennerstrom graduated from Cal State Fullerton and ran track. He also created one of the first women’s track publications, Women’s Track and Field World. The collection covers everything from strongwomen and circus performers to bodybuilding and powerlifting. It is truly an amazing knowledge base for bodybuilding and sports fans everywhere, especially those interested in the rise of women’s sports throughout the recent decades. Access Access to the Steve Wennerstrom Papers is restricted to visitors of the H.J. Lutcher Stark Center for Physical Culture and Sports and must be requested in writing prior to arrival at the Center. Furthermore, certain items in the collection (as identified below) are not suitable to be viewed by minors. The research request/proposal should explain the proposed project, the expected outcome, and institutional affiliation, if any. Requests should be sent to: Dr. Jan Todd at [email protected]. -

Esprit De Corps: a History of North American Bodybuilding James Woycke Western University, [email protected]

Western University Scholarship@Western History eBook Collection eBook Collections 2016 Esprit de Corps: A History of North American Bodybuilding James Woycke Western University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://ir.lib.uwo.ca/historybooks Part of the Social History Commons Recommended Citation Woycke, James, "Esprit de Corps: A History of North American Bodybuilding" (2016). History eBook Collection. 2. https://ir.lib.uwo.ca/historybooks/2 This Book is brought to you for free and open access by the eBook Collections at Scholarship@Western. It has been accepted for inclusion in History eBook Collection by an authorized administrator of Scholarship@Western. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. Esprit de Corps A History of North American Bodybuilding James Woycke Copyright c 2016 Esprit de Corps i Foreword Years ago, while researching another topic, Jim Woycke met body- builder photographer Tony Lanza who recounted many first-hand ac- counts of the early years of bodybuilding. Looking for more informa- tion, Jim discovered that, apart from some biographies of bodybuilders, there was little material on the sport, and less about Montreal brothers Ben and Joe Weider, founders of modern bodybuilding. Consequently, Jim resolved to write a comprehensive history. He researched the topic exhaustively in Canadian and American archives and libraries, and conducted several interviews. He met with Ben Weider in Montreal, who allowed him to read and photocopy all Weider magazines dating from 1940, and to quote from, and reprint photographs. Jim is the only researcher in the field to have read French language sources, uncovering Adrien Gagnon’s role in bodybuilding, especially his bitter rivalry with the Weiders. -

Fierce Not Freaky

Fierce not Freaky The Simultaneous Incorporation, Dismissal and Adjustment of Dominant Norms of Femininity by Female Bodybuilders in Contemporary Australia. Written by Freya Nadine Lambrechts University of Amsterdam Research Master Social Sciences GSSS 10266704 Supervised by dr. R. Spronk Second Reader; dr. C.M. Roggeband 1st of May 2018, Amsterdam 2 Acknowledgements I like to dedicate this thesis to the strong women who participated in my research. Without their collaboration this master thesis would have never existed. They surprised me with their willingness to, not only give me their time but also to share their deepest thoughts and feelings. They opened up to me, trusted me and therefore allowed me to create a deeper scientific understanding of their lives and their bodybuilding ambitions. Their openness and generosity form the beating heart of this work and therefore I am incredible grateful. I would also like to thank a few persons who made this thesis possible. First of all, my parents for their ongoing support and patience throughout my university career. Their endless optimism and the statement that ‘everything is going to be okay’ did turn out to be true in the end. Secondly, I would like to thank my friends who reminded me that there is a life outside of the academia and made me happier person on a day-to-day basis. Last, I would like to thank my supervisor dr. Rachel Spronk who took a difficult case (me) and guided me through this extensive project. 3 4 Table of contents Introduction 6 Chapter 1: The sport bodybuilding The history, organization and development of bodybuilding in Australia 15 Chapter 2: Becoming a bodybuilder The inspirations and motivations of women to participate in bodybuilding 34 Chapter 3: Bodybuilding & biowpower The influence of biopower on the female bodybuilder 57 Chapter 4: Muscular yet feminine The complex construction of muscularity, masculinity and femininity in women’s bodybuilding 78 Conclusion 103 Bibliography 108 5 Introduction ‘It’s genuinely indescribable. -

Women, Sport and Ethnicity: Exploring Experiences of Difference in Netball

WOMEN, SPORT AND ETHNICITY: EXPLORING EXPERIENCES OF DIFFERENCE IN NETBALL Tracy Lynn Taylor Submitted for the qualification of: Doctor of Philosophy 2000 Acknowledgments I would like to express my appreciation to the following individuals for their guidance, assistance, motivation and perseverance in the completion of this thesis. From the initial selection of the topic, through its various stages of conceptualisation and re conceptualisation through to completion my supervisor, Richard Cashman, has been invaluable. Richard provided direction and feedback that allowed me the opportunity to move at my own pace and in my own way. In particular, his eye for detail was greatly appreciated. I would also like to acknowledge Kristine Toohey’s role in partnering a number of research projects from which the idea for this thesis emerged. Researching cultural diversity presented a huge learning curve for both of us and opened my eyes to a different way of looking at sports organisation and discourse. My appreciation also to Tony Veal and Bob Barney who agreed to read and comment on the final draft and probably didn’t know what they were in for! Many thanks for your insightful comments and generously giving up your leisure time to do so! Finally, my appreciation to Peter McGraw for his proof-reading skills, suggestions on structure and language, and honest appraisal of content. Certificate of Originality I hereby declare that this submission is my own work and to the best of my knowledge it contains no materials previously published or written by another person, nor material to a substantial extent has been accepted for the award of any other degree or diploma at UNSW or any other educational institution except where due acknowledgement is made in the thesis. -

Not Simply Women's Bodybuilding: Gender and the Female Competition Categories

Georgia State University ScholarWorks @ Georgia State University Institute for Women's, Gender, and Sexuality Women's, Gender, and Sexuality Studies Theses Studies Spring 5-1-2013 Not Simply Women's Bodybuilding: Gender and the Female Competition Categories Sheena A. Hunter Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.gsu.edu/wsi_theses Recommended Citation Hunter, Sheena A., "Not Simply Women's Bodybuilding: Gender and the Female Competition Categories." Thesis, Georgia State University, 2013. https://scholarworks.gsu.edu/wsi_theses/27 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Institute for Women's, Gender, and Sexuality Studies at ScholarWorks @ Georgia State University. It has been accepted for inclusion in Women's, Gender, and Sexuality Studies Theses by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks @ Georgia State University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. NOT SIMPLY WOMEN’S BODYBUILDING: GENDER AND THE FEMALE COMPETITION CATEGORIES by SHEENA A. HUNTER Under the Direction of Dr. Megan Sinnott ABSTRACT Once known only as Bodybuilding and Women’s Bodybuilding, the sport has grown to include multiple competition categories that both limit and expand opportunities for female bodybuilders. While the creation of additional categories, such as Fitness, Figure, Bikini, and Physique, appears to make the sport more inclusive to more variations and interpretation of the feminine, muscular physique, it also creates more in-between spaces. This auto ethnographic research explores the ways that multiple female competition categories within the sport of Bodybuilding define, reinforce, and complicate the gendered experiences of female physique athletes, by bringing freak theory into conversation with body categories. INDEX WORDS: Women’s bodybuilding, Gender performativity, Femininity, Gender, Freaks, Competition categories, In-betweenness, Stuckness NOT SIMPLY WOMEN’S BODYBUILDING: GENDER AND THE FEMALE COMPETITION CATEGORIES by SHEENA A. -

AA Statistician, Fletcher Mcewen & David

all-time AUSTRALIAN ALL-TIME LIST As at 1st September 2019 Compiled by Paul Jenes - AA Statistician, Fletcher McEwen & David Tarbotton PERFORM WIND NAME ASS DOB PLACEVENUE DATE MEN 100 YARDS 9.52 -0.8 Gary Eddy V 260345 5 Kingston,Jamaica 6 Aug 66 9.56 Matt Shirvington N 251078 1 Sydney 21 Jan 00 9.62 Patrick Johnson A 260972 2 Sydney 21 Jan 00 manual 9.2 +1.4 Bob Lay N 200344 1 Sydney 10 Mar 65 9.3 +0.0 Hec Hogan Q 110731 1 Sydney 13 Mar 54 9.3 Ken Irvine N 050340 1 Dubbo 9 Mar 63 9.3 Gary Holdsworth V 010841 1 Melbourne 6 Mar 66 9.3 Richard James V 090356 1 Melbourne 20 Dec 79 9.3 Peter Batten V 190956 2 Melbourne 20 Dec 79 9.3 Rod Mapstone W 191169 1 Sydney 3 Mar 86 9.4 Peter Vassella N 040141 1 Wollongong 4 Mar 62 9.4 Greg Lewis V 091246 2 Melbourne 16 Mar 66 9.4 Stuart Laing Q 220146 1 Melbourne 10 Feb 68 9.4 Gary Eddy V 260345 1 Melbourne 24 Jan 70 9.4 Fred Martin N 041066 1 Sydney 13 Feb 85 100 METRES 9.93 +1.8 Patrick Johnson A 260972 1 Mito,Japan 5 May 03 10.03 -0.1 Matt Shirvington N 251078 4 Kuala Lumpur,Malaysia 17 Sep 98 10.08 +1.9 Joshua Ross N 090281 1 Brisbane 10 Mar 07 10.08 +2.0 Rohan Browning N 311297 2rA Brisbane 23 Mar 19 10.10 +0.4 Trae Williams Q 050597 1 Gold Coast 16 Feb 18 10.13 +0.1 Damien Marsh Q 280371 1 Monte Carlo, Monaco 9 Sep 95 10.15 +0.8 Josh Clarke N 190595 1 Canberra 6 Feb 16 10.15 +1.5 Jake Doran Q 170700 1rA Jämsä, Finland 1 Jul 18 10.17 +2.0 Rod Mapstone W 191169 2h Perth 28 Jan 96 10.17 +0.9 Adam Miller N 220684 1s Brisbane 10 Mar 07 10.17 +1.8 Aaron Rouge-Serret V 280188 1 Perth 26 Mar 10 10.18