Check the Rhime!

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A True Story

PARANOIA: A TRUE STORY 1. Paranoia feat. Jeezy 5. Jazzy Interlude 8. Maneuver feat. French Montana 12. Wanna Be Me (David Brewster, Gary Evan Fountaine, Jay Jenkins) • Freaky (Daniel Garcia, Francis Ubiera, Jazmine Pena, Julian Jackson, (David Brewster, Rory William Quigley, Karim Kharbouch, (David Brewster, Joe Cruz) • Freaky Forever Publishing/ Forever Publishing/These Are Pulse Songs (BMI)//Keyboard Brion James, Janice Johnson) • Buda Da Future Publishing Nasir Jones, Peter Phillips) • Freaky Forever Publishing/ These Are Pulse Songs (BMI)//Joe Joe Beats (ASCAP) • Koke (ASCAP)//Young Jeezy Music/EMI Blackwood (BMI) • (BMI)//Grandz Music Publishing (BMI)//Copyright Control// These Are Pulse Songs (BMI)//Fraud Beats, Inc. (BMI)// Produced by Joe Joe Beats • Recorded by Jeff “RAMZY” Produced by Nonstop Da Hitman of 808 Mafia • Recorded by Jam Shack Music/Naked Soul Music/Trey Three Music • Excuse My French/Sony/ATV Allegro (ASCAP)//Universal Ramirez at Quad Recording Studio, NYC • Mixed by Fabian Jeff “RAMZY” Ramirez at Quad Recording Studio, NYC and by Produced by Buda & Grandz • Recorded by Jeff “RAMZY” Music – Z Songs (BMI) o/b/o itself and Sun Shining, Marasciullo for that’s a dope mix at Just Us Studios • John Scott at The Embassy, Atlanta, GA • Mixed by Fabian Ramirez at Quad Recording Studio, NYC • Contains an Inc.//Reach Global Inc. administered by BMG Rights Assistant Mix Engineer: McCoy Socalgargoyle Marasciullo for ‘that’s a dope mix’ at Just Us Studios • interpolation of “Kissin’ You” written by Julian Jackson, Management US, LLC (ASCAP) • Produced by Harry Fraud Assistant Mix Engineer: McCoy Socalgargoyle Brion James and Janice Johnson.Published by Jam Shack • Recorded by Harry Fraud at Quad Recording Studio, 13. -

Kaya Hip-Hop in Coastal Kenya: the Urban Poetry of UKOO FLANI

Page 1 of 46 Kaya Hip-Hop in Coastal Kenya: The Urban Poetry of UKOO FLANI By: Divinity LaShelle Barkley [email protected] Academic Director: Athman Lali Omar I.S.P. Advisor: Professor Mohamed Abdulaziz S.I.T. Kenya, Fall 2007 Coastal Cultures & Swahili Studies Kaya Hip Hop in Coastal Kenya Fall 2007 ISP, SIT Kenya By: Divinity L. Barkley Page 2 of 46 Table of Contents Acknowledgements………………………………………..………………….page 3 Abstract……………………………………………..…………………………page 4 Introduction…………………………………..……………………………pages 5-8 Hip-Hop & Kenyan Youth Culture Research Problem Status of Hip-Hop in Kenya Hypotheses The Setting……………………………….………………………………pages 9-10 Methodology: Data Collection……………………………………..…pages 10-12 Biases and Assumptions………………………..………...…………...pages 13-14 Discussion & Analysis…………………………………………………pages 14-38 Ukoo Flani ni nani? Kaya Hip-Hop Traditional Role of Music in African Culture Genesis of Rap/Hip-hop in American Ghettoes The Ties That Bind Kenyan Radio The Maskani Ghetto Life Will the real Ukoo Flani please stand up? Urban Poetry: Analyzing Ukoo Flani’s Lyrics Conclusion…………………………..……………………….…………pages 38-42 Conclusion Part I: The Future of Ukoo Flani Conclusion Part II: Hypotheses Results Conclusion Part III: Recommendations for Future SIT Students Bibliography………………………………………………..…………..pages 43-44 Interview/Meeting Schedule………………………………………………page 45 ISP Review Sheet…………….……………………………………….……page 46 Kaya Hip Hop in Coastal Kenya Fall 2007 ISP, SIT Kenya By: Divinity L. Barkley Page 3 of 46 Acknowledgements First and foremost, I would like to thank the entire Ukoo Flani crew for their contributions to my project. I am fascinated by your amazing talent and dedication to making positive music to inspire future generations. I am amazed at what you have been able to accomplish despite limited access to resources. -

112. Na Na Na 112. Only You Remix 112. Come See Me Remix 12

112. Na Na Na 112. Only You Remix 112. Come See Me Remix 12 Gauge Dunkie Butt 12 Gauge Dunkie Butt 2 Live Crew Sports Weekend 2nd II None If You Want It 2nd II None Classic 220 2Pac Changes 2Pac All Eyez On Me 2Pac All Eyez On Me 2Pac I Get Around / Keep Ya Head Up 50 Cent Candy Shop 702. Where My Girls At 7L & Esoteric The Soul Purpose A Taste Of Honey A Taste Of Honey A Tribe Called Quest Unreleased & Unleashed Above The Law Untouchable Abyssinians Best Of The Abyssinians Abyssinians Satta Adele 21. Adele 21. Admiral Bailey Punanny ADOR Let It All Hang Out African Brothers Hold Tight (colorido) Afrika Bambaataa Renegades Of Funk Afrika Bambaataa Planet Rock The Album Afrika Bambaataa Planet Rock The Album Agallah You Already Know Aggrolites Rugged Road (vinil colorido) Aggrolites Rugged Road (vinil colorido) Akon Konvicted Akrobatik The EP Akrobatik Absolute Value Al B. Sure Rescue Me Al Green Greatest Hits Al Johnson Back For More Alexander O´Neal Criticize Alicia Keys Fallin Remix Alicia Keys As I Am (vinil colorido) Alicia Keys A Woman´s Worth Alicia Myers You Get The Best From Me Aloe Blacc Good Things Aloe Blacc I Need A Dollar Alpha Blondy Cocody Rock Althea & Donna Uptown Top Ranking (vinil colorido) Alton Ellis Mad Mad Amy Winehouse Back To Black Amy Winehouse Back To Black Amy Winehouse Lioness : The Hidden Treasures Amy Winehouse Lioness : The Hidden Treasures Anita Baker Rapture Arthur Verocai Arthur Verocai Arthur Verocai Arthur Verocai Augustus Pablo King Tubby Meets Rockers Uptown Augustus Pablo In Fine Style Augustus Pablo This Is Augustus Pablo Augustus Pablo Dubbing With The Don Augustus Pablo Skanking Easy AZ Sugar Hill B.G. -

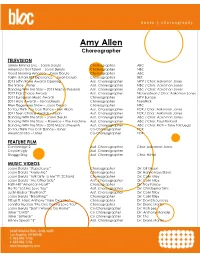

Amy Allen Choreographer

Amy Allen Choreographer TELEVISION Jimmy Kimmel Live – Jason Derulo Choreographer ABC America’s Got Talent – Jason Derulo Choreographer NBC Good Morning America – Jason Derulo Choreographer ABC 106th & Park BET Experience – Jason Derulo Choreographer BET 2013 MTV Movie Awards Opening Asst. Choreographer MTV / Chor: Aakomon Jones The Voice – Usher Asst. Choreographer NBC / Chor: Aakomon Jones Dancing With the Stars – 2013 Macy’s Presents Asst. Choreographer ABC / Chor: Aakomon Jones 2012 Kids Choice Awards Asst. Choreographer Nickelodeon / Chor: Aakomon Jones 2011 European Music Awards Choreographer MTV Europe 2011 Halo Awards – Jason Derulo Choreographer TeenNick Ellen Degeneres Show – Jason Derulo Choreographer NBC So You Think You Can Dance – Keri Hilson Asst. Choreographer FOX / Chor: Aakomon Jones 2011 Teen Choice Awards – Jason Asst. Choreographer FOX / Chor: Aakomon Jones Dancing With the Stars – Jason Derulo Asst. Choreographer ABC / Chor: Aakomon Jones Dancing With the Stars – Florence + The Machine Asst. Choreographer ABC / Chor: Paul Kirkland Dancing With the Stars – 2010 Macy’s Presents Asst. Choreographer ABC / Chor: Rich + Tone Talauega So You Think You Can Dance – Usher Co-Choreographer FOX American Idol – Usher Co-Choreographer FOX FEATURE FILM Centerstage 2 Asst. Choreographer Chor: Aakomon Jones Coyote Ugly Asst. Choreographer Shaggy Dog Asst. Choreographer Chor: Hi Hat MUSIC VIDEOS Jason Derulo “Stupid Love” Choreographer Dir: Gil Green Jason Derulo “Marry Me” Choreographer Dir: Hannah Lux Davis Jason Derulo “Talk Dirty To Me” ft. 2Chainz Choreographer Dir: Colin Tilley Jason Derulo “The Other Side” Asst. Choreographer Dir: Colin Tilley Faith Hill “American Heart” Choreographer Dir: Trey Fanjoy Ne-Yo “Let Me Love You” Asst. Choreographer Dir: Christopher Sims Justin Bieber “Boyfriend” Asst. -

M I K E S a R K I S S I a N Credits

MIKE SARKISSIAN CREDITS _____________________________________________________________________________ EXECUTIVE PRODUCER / PRODUCER FILM The White Stripes Under Great White Northern Lights Emmett Malloy Jack Johnson En Concert Emmett Malloy Jack Johnson A Weekend at the Greek Emmett Malloy Jack White Jack White Kneeling at The Anthem Emmett Malloy TV Paramount Dream: Birth of the Modern Athlete The Malloy Brothers National Geographic Breakthrough Season 2 Series Producer Revolution Studios Pilot – Everyday People Tim Wheeler GSN / Revolution Studios Drew Carey’s Improv-A-ganza 40 eps Liz Zannin The Dead Weather Live at the ROXY Tim Wheeler Jack Johnson Kokua Festival 05-09 Emmett Malloy From The Basement Raconteurs / Kills / Fleet Foxes Nigel Godrich From The Basement Queens of the Stone Age Nigel Godrich Sundance Channel 5 Years of Change – KOKUA Emmett Malloy Selena Gomez Girl Meets World – Disney Channel Tim Wheeler James Blunt Live & SPPP Studios Tim Wheeler Disney Channel Radio Disney Concert Special Tim Wheeler Nickelback Live at Home Nigel Dick Marie Digby Live At Rick Ruben Studios Mike Piscitelli Grace Potter Live In Burlington Tim Wheeler Alpha Rev Live @SPPP Studios Tim Wheeler Kate Vogel Live @SPPP Studios Tim Wheeler ZZ Ward Live @ The Troubadour Tim Wheeler Nick Jonas Live @ Capitol Records Giles Dunning Grace Potter Live @ The Waterfront Tim Wheeler R5 Live @ the O2 London Tim Wheeler COMMERCIALS Honda Happy Honda Days ’19 Campain Jed Hathaway Apple Apple TV+ 2019 March Launch Robin Cosimir Waze Waze Carpool Jeff + Pete Accenture Talent, Resilience, Disruption Jordan Bahat Google Google Cloud Jordan Bahat Amazon Fire TV Twin Peaks Pie Shop, Playlist Jeff + Pete Always Prepared, No Chance Whip It, Whip it Good Sharknado by the Sea Chicken Little Fingers Dove Real Moms Acura Emotion Is In IBM / Watson Not Easy Nicolas Davenel Max Factor Miracle Touch Camilla Akrins Visa Snapchat / Olympics Giles Dunning McDonalds Fans vs Critics Jordan Bahat Navy Federal Credit Union Veterans Bond Jeff + Pete Dr. -

Tom Jennings

12 | VARIANT 30 | WINTER 2007 Rebel Poets Reloaded Tom Jennings On April 4th this year, nationally-syndicated Notes US radio shock-jock Don Imus had a good laugh 1. Despite the plague of reactionary cockroaches crawling trading misogynist racial slurs about the Rutgers from the woodwork in his support – see the detailed University women’s basketball team – par for the account of the affair given by Ishmael Reed, ‘Imus Said Publicly What Many Media Elites Say Privately: How course, perhaps, for such malicious specimens paid Imus’ Media Collaborators Almost Rescued Their Chief’, to foster ratings through prejudicial hatred at the CounterPunch, 24 April, 2007. expense of the powerless and anyone to the left of 2. Not quite explicitly ‘by any means necessary’, though Genghis Khan. This time, though, a massive outcry censorship was obviously a subtext; whereas dealing spearheaded by the lofty liberal guardians of with the material conditions of dispossessed groups public taste left him fired a week later by CBS.1 So whose cultures include such forms of expression was not – as in the regular UK correlations between youth far, so Jade Goody – except that Imus’ whinge that music and crime in misguided but ominous anti-sociality he only parroted the language and attitudes of bandwagons. Adisa Banjoko succinctly highlights the commercial rap music was taken up and validated perspectival chasm between the US civil rights and by all sides of the argument. In a twinkle of the hip-hop generations, dismissing the focus on the use of language in ‘NAACP: Is That All You Got?’ (www.daveyd. -

Cass Citv Class Of

manager in prison ‘ITY0 CHRONICLE VOLUME 96, NUM LAS~LI I 1, lvlICHIGAN - WEDNESDAY, APRIL IO, 2002 FIFTYCENTS * 16 PAGES PLUS ONE SUPPLEMENT Board of For Emmert. Storm education racewet Benefit dinner School board races are sct ’ in at least 3 area districts, in- cluding Cass City, following generates $42,000 Monday’s 4 pm.dcadline to file nominating petitions and Affidavits of Identity. The figure is $42,000 and The Cnss City National Tech Center and posters were The regular school elec- still rising as the Cass City Honor Society members and created by the Cass City High tions are scheduled for Mon- and Thumb community the student council provided School Art Class. day, June IO, came to together in an aston- help on the floor and in clean- Family buLtons sold at the A trio of candidates is vy- ishingly successful benefit up crews. Placemats with pic- door were created by middle ing for a single, 4-year term dinner Sunday for 2 Cass turt‘s of Storm and Emincrt school students. There was on the Cass City Board of City youths suffering from came from students at the Please turn to page 5. Education. Newcomers cancer. Larry Bogart and Dawn The money was raised for Prieskorn are challenging Ryan Storm, 14, son of Frank incumbent Trustee Randy and Karen Storm and Alison Severance. Emmert, 16, daughter of Britt retiring In other area districts: Chuck and Amy Emmert. OWEN-GAGE The banquet netted $2 1,000 and that amount was Five candidates will battle matched by the Aid Associa- for a pair of 4-year terms in after 3 / years tion for LutheransLutheran the Owen-Gage School Dis- Brotherhood, branch number trict. -

1. Summer Rain by Carl Thomas 2. Kiss Kiss by Chris Brown Feat T Pain 3

1. Summer Rain By Carl Thomas 2. Kiss Kiss By Chris Brown feat T Pain 3. You Know What's Up By Donell Jones 4. I Believe By Fantasia By Rhythm and Blues 5. Pyramids (Explicit) By Frank Ocean 6. Under The Sea By The Little Mermaid 7. Do What It Do By Jamie Foxx 8. Slow Jamz By Twista feat. Kanye West And Jamie Foxx 9. Calling All Hearts By DJ Cassidy Feat. Robin Thicke & Jessie J 10. I'd Really Love To See You Tonight By England Dan & John Ford Coley 11. I Wanna Be Loved By Eric Benet 12. Where Does The Love Go By Eric Benet with Yvonne Catterfeld 13. Freek'n You By Jodeci By Rhythm and Blues 14. If You Think You're Lonely Now By K-Ci Hailey Of Jodeci 15. All The Things (Your Man Don't Do) By Joe 16. All Or Nothing By JOE By Rhythm and Blues 17. Do It Like A Dude By Jessie J 18. Make You Sweat By Keith Sweat 19. Forever, For Always, For Love By Luther Vandros 20. The Glow Of Love By Luther Vandross 21. Nobody But You By Mary J. Blige 22. I'm Going Down By Mary J Blige 23. I Like By Montell Jordan Feat. Slick Rick 24. If You Don't Know Me By Now By Patti LaBelle 25. There's A Winner In You By Patti LaBelle 26. When A Woman's Fed Up By R. Kelly 27. I Like By Shanice 28. Hot Sugar - Tamar Braxton - Rhythm and Blues3005 (clean) by Childish Gambino 29. -

Songs by Title Karaoke Night with the Patman

Songs By Title Karaoke Night with the Patman Title Versions Title Versions 10 Years 3 Libras Wasteland SC Perfect Circle SI 10,000 Maniacs 3 Of Hearts Because The Night SC Love Is Enough SC Candy Everybody Wants DK 30 Seconds To Mars More Than This SC Kill SC These Are The Days SC 311 Trouble Me SC All Mixed Up SC 100 Proof Aged In Soul Don't Tread On Me SC Somebody's Been Sleeping SC Down SC 10CC Love Song SC I'm Not In Love DK You Wouldn't Believe SC Things We Do For Love SC 38 Special 112 Back Where You Belong SI Come See Me SC Caught Up In You SC Dance With Me SC Hold On Loosely AH It's Over Now SC If I'd Been The One SC Only You SC Rockin' Onto The Night SC Peaches And Cream SC Second Chance SC U Already Know SC Teacher, Teacher SC 12 Gauge Wild Eyed Southern Boys SC Dunkie Butt SC 3LW 1910 Fruitgum Co. No More (Baby I'm A Do Right) SC 1, 2, 3 Redlight SC 3T Simon Says DK Anything SC 1975 Tease Me SC The Sound SI 4 Non Blondes 2 Live Crew What's Up DK Doo Wah Diddy SC 4 P.M. Me So Horny SC Lay Down Your Love SC We Want Some Pussy SC Sukiyaki DK 2 Pac 4 Runner California Love (Original Version) SC Ripples SC Changes SC That Was Him SC Thugz Mansion SC 42nd Street 20 Fingers 42nd Street Song SC Short Dick Man SC We're In The Money SC 3 Doors Down 5 Seconds Of Summer Away From The Sun SC Amnesia SI Be Like That SC She Looks So Perfect SI Behind Those Eyes SC 5 Stairsteps Duck & Run SC Ooh Child SC Here By Me CB 50 Cent Here Without You CB Disco Inferno SC Kryptonite SC If I Can't SC Let Me Go SC In Da Club HT Live For Today SC P.I.M.P. -

Institute for Studies in American Music Conservatory of Music, Brooklyn College of the City University of New York NEWSLETTER Volume XXXIV, No

Institute for Studies In American Music Conservatory of Music, Brooklyn College of the City University of New York NEWSLETTER Volume XXXIV, No. 2 Spring 2005 Jungle Jive: Jazz was an integral element in the sound and appearance of animated cartoons produced in Race, Jazz, Hollywood from the late 1920s through the late 1950s.1 Everything from big band to free jazz and Cartoons has been featured in cartoons, either as the by soundtrack to a story or the basis for one. The studio run by the Fleischer brothers took an Daniel Goldmark unusual approach to jazz in the late 1920s and the 1930s, treating it not as background but as a musical genre deserving of recognition. Instead of using jazz idioms merely to color the musical score, their cartoons featured popular songs by prominent recording artists. Fleischer was a well- known studio in the 1920s, perhaps most famous Louis Armstrong in the jazz cartoon I’ll Be Glad When for pioneering the sing-along cartoon with the You’ re Dead, You Rascal You (Fleischer, 1932) bouncing ball in Song Car-Tunes. An added attraction to Fleischer cartoons was that Paramount Pictures, their distributor and parent company, allowed the Fleischers to use its newsreel recording facilities, where they were permitted to film famous performers scheduled to appear in Paramount shorts and films.2 Thus, a wide variety of musicians, including Ethel Merman, Rudy Vallee, the Mills Brothers, Gus Edwards, the Boswell Sisters, Cab Calloway, and Louis Armstrong, began appearing in Fleischer cartoons. This arrangement benefited both the studios and the stars. -

AN ANALYSIS of the MUSICAL INTERPRETATIONS of NINA SIMONE by JESSIE L. FREYERMUTH B.M., Kansas State University, 2008 a THESIS S

AN ANALYSIS OF THE MUSICAL INTERPRETATIONS OF NINA SIMONE by JESSIE L. FREYERMUTH B.M., Kansas State University, 2008 A THESIS submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree MASTER OF MUSIC Department of Music College of Arts and Sciences KANSAS STATE UNIVERSITY Manhattan, Kansas 2010 Approved by: Major Professor Dale Ganz Copyright JESSIE L. FREYERMUTH 2010 Abstract Nina Simone was a prominent jazz musician of the late 1950s and 60s. Beyond her fame as a jazz musician, Nina Simone reached even greater status as a civil rights activist. Her music spoke to the hearts of hundreds of thousands in the black community who were struggling to rise above their status as a second-class citizen. Simone’s powerful anthems were a reminder that change was going to come. Nina Simone’s musical interpretation and approach was very unique because of her background as a classical pianist. Nina’s untrained vocal chops were a perfect blend of rough growl and smooth straight-tone, which provided an unquestionable feeling of heartache to the songs in her repertoire. Simone also had a knack for word painting, and the emotional climax in her songs is absolutely stunning. Nina Simone did not have a typical jazz style. Critics often described her as a “jazz-and-something-else-singer.” She moved effortlessly through genres, including gospel, blues, jazz, folk, classical, and even European classical. Probably her biggest mark, however, was on the genre of protest songs. Simone was one of the most outspoken and influential musicians throughout the civil rights movement. Her music spoke to the hundreds of thousands of African American men and women fighting for their rights during the 1960s. -

Nasir Album Free Zip Download Nas Album Download Zip

nasir album free zip download Nas Album Download Zip. Nas wrote “the kids are our future” along with the unveiling, which could be an underlining theme or message to the project. “Nas sounds like 2028 Nas,” Pusha-T told Angie Martinez last month. “With Nas particularly, ‘Ye is such a fan that he can pull all the greatest moments in seven songs, and update that energy. Peruzzi – Heartwork (EP) (Album) Download Beautiful Nubia – More Tales from a Small Room (Album) Download Beautiful Nubia – Tales From A Small Room (Album) Download. Nas – NASIR Album (Zip Download) Nas NASIR Album Nas’ 11th solo album Nasir was, until recently, a secret to all but his inner sanctum. Few even knew it was coming until its producer Latest on 2019: Nas – NASIR Album (Zip Download) mp3 download music, mp4 video, news. Nas Album Download Free. FULL ALBUM: Nas – NASIR Zippyshare mp3 torrent download Listen To And Download Nas New Album NASIR (zip/mp3/itunes) By Nas Tracklist 1. Nas – Everything ft. Kanye West & The-Dream // DOWNLOAD MP3 2. Nas – Bonjour // DOWNLOAD MP3 3. Nas – Not For Radio Ft 070 Shake // DOWNLOAD MP3 4. Nas – Adam And Eve // DOWNLOAD MP3 5. Nas Nasir Album Zip Download. Nas – Simple Things // DOWNLOAD MP3 6. Nas – Cops ft. Kanye West // DOWNLOAD MP3 7. Nas – I’m Gonna Have To Leave You // DOWNLOAD MP3 Download FULL ALBUM: Nas – NASIR Zippyshare mp3 torrent. Nas – King’s Disease Album Zip Free Download. The 13-track venture incorporates the Hit-Boy-assisted single “Ultra Back” and appearances from Don Toliver and Big Sean on “Supplant Me,” Charlie Wilson on “Vehicle #85,” Lil Durk on “Until The War Is Won,” Anderson .Paak on “All Bad,” Brucie B.