(Maria) Buesink 563091

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Second Try

The Second Try Jimmy Wolk Chapter I: The 12th Shinji Ikari, Third Children and designated pilot of Evangelion Unit-01, had just reached a new sync- ratio record. And as Rei Ayanami suspected, the former holder of this record, known as Asuka Langley Soryu, wasn't very pleased with this. So she didn't pay much attention to the rants of the Second Children, who made obviously ironical statements about the 'great, invincible Shinji' while holding herself; swaying in front of her locker. Instead, Rei finished changing from the plugsuit the pilots were supposed to wear during their time in the entry plugs of the EVAs or the test plugs, into her casual school uniform. As soon as she was done, she went silently for the door of the female pilots' changing room, whispered "Sayonara" and left. With the First Children gone, Asuka could finally release all the feelings that tensed up the last hours in a powerful... ...sigh. She still had problems to play this charade in front of everyone, and it seemed to only grow harder. She wasn't sure if she would be able to keep it up much longer at all. Not while these thoughts disturbed her mind; thoughts of all the things that happened... or will happen soon. Lost in her worries, she failed to notice someone entering the room, sneaking up to her and suddenly embracing her from behind; encircling her arms with his own. She tensed up noticeably as she felt the touch, even though (or maybe just because) she knew exactly who the stranger was. -

Archiving Movements: Short Essays on Materials of Anime and Visual Media V.1

Contents Exhibiting Anime: Archive, Public Display, and the Re-narration of Media History Gan Sheuo Hui ………… 2 Utilizing the Intermediate Materials of Anime: Royal Space Force: The Wings of Honnêamise Ishida Minori ………… 17 The Film through the Archive and the Archive through the Film: History, Technology and Progress in Royal Space Force: The Wings of Honnêamise Dario Lolli ………… 25 Interview with Yamaga Hiroyuki, Director of Royal Space Force: The Wings of Honnêamise What Do Archived Materials Tell Us about Anime? Kim Joon Yang ………… 31 Exhibiting Manga: Impulses to Gain from the Archiving/Unearthing Anime Project Jaqueline Berndt ………… 36 Analyzing “Regional Communities” with “Visual Media” and “Materials” Harada Ken’ichi ………… 41 About the Archive Center for Anime Studies in Niigata University ………… 45 Exhibiting Anime: Archive, Public Display, and the Re-narration of Media History Gan Sheuo Hui presumably, the majority are in various storage Background of the Project places after their production cycles. It is not The exhibition “A World is Born: The uncommon that they are forgotten, displaced or Emerging Arts and Designs in 1980s Japanese eventually discarded due to the expenses incurred Animation” (19-31 March 2018) hosted at DECK, for storage. In many ways, these materials an independent art space in Singapore, is encompass an often forgotten yet significant part of an ongoing research collaboration research resource essential for understanding between the researchers from Puttnam School key aspects of Japanese animation production of Film and Animation in Singapore and the cultures and practices. Archive Center for Anime Studies in Niigata “A World is Born” was an exhibition focusing University (ACASiN). -

Dark Matter #4

Cover Page DarkIssue Four Matter July 2011 SF, Fantasy & Art [email protected] Dark Matter Issue Four July 2011 SF, Fantasy & Art [email protected] Dark Matter Contents: Issue 4 Dark Matter Stuff 1 News & Articles 7 Gun Laws & Cosplay 7 Troopertrek 2011 8 Hugo Award Nominees 10 2010 Aurealis Awards 14 2011 Aurealis Awards to be held in Sydney again 15 2011 Ditmar Awards 16 2011 Chronos Awards 20 Renovation WorldCon 22 Iron Sky update 28 Art by Ben Grimshaw 30 Ebony Rattle as Electra, Art by Ben Grimshaw 31 The Girl in the Red Hood is Back … But She’s a Little Different 32 Launching & Gaining Velocity 34 Geek and Nerd 35 Peacemaker - A Comic Book 36 Continuum 7 Report 38 Starcraft 2 - Prae.ThorZain 46 Good Friday Appeal 50 FAQ about the writing of Machine Man, by Max Barry 65 J. Michael Straczynski says... 67 Interviews 69 Kevin J. Anderson talks to Dark Matter 69 Tom Taylor and Colin Wilson talk to Dark Matter 78 Simon Morden talks to Dark Matter 106 Paul Bedford talks to Dark Matter 115 Cathy Larsen talks to Dark Matter 131 Madeleine Roux talks to Daniel Haynes 142 Chewbacca is Coming 146 Greg Gates talks to Dark Matter 153 Richard Harland talks to Dark Matter 165 Letters 173 Anime/Animation 176 The Sacred Blacksmith Collection 176 Summer Wars 177 Evangelion 1.11 You are [not] alone 178 Evangelion 2.22 You can [not] advance 179 Book Reviews 180 The Razor Gate 180 Angelica 181 2 issue four The Map of Time 182 Die for Me 183 The Gathering 184 The Undivided 186 the twilight saga: the official illustrated guide 188 Rivers -

Viewed and Discussed in Wired Magazine (Horn), Japan's National Newspaper the Daily Yomiuri (Takasuka),And the Mainichi Shinbun (Watanabe)

Florida State University Libraries Electronic Theses, Treatises and Dissertations The Graduate School 2008 You Are Not Alone: Self-Identity and Modernity in Neon Genesis Evangelion and Kokoro Claude Smith III Follow this and additional works at the FSU Digital Library. For more information, please contact [email protected] FLORIDA STATE UNIVERSITY COLLEGE OF ASIAN STUDIES YOU ARE NOT ALONE: SELF-IDENTITY AND MODERNITY IN NEON GENESIS EVANGELION AND KOKORO By CLAUDE SMITH III A Thesis submitted to the Department of Asian Studies in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts Degree Awarded: Fall Semester, 2008 The members of the Committee approve the Thesis of Claude Smith defended on October 24, 2008 . __________________________ Yoshihiro Yasuhara Professor Directing Thesis __________________________ Feng Lan Committee Member __________________________ Kathleen Erndl Committee Member The Office of Graduate Studies has verified and approved the above named committee members. ii My paper is dedicated in spirit to David Lynch, Anno Hideaki, Kojima Hideo, Clark Ashton Smith, Howard Phillips Lovecraft, and Murakami Haruki, for showing me the way. iii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I would like very much to thank Dr. Andrew Chittick and Dr. Mark Fishman for their unconditional understanding and continued support. I would like to thank Dr. Feng Lan, Dr. Erndl, and Dr. Yasuhara. Last but not least, I would also like to thank my parents, Mark Vicelli, Jack Ringca, and Sean Lawler for their advice and encouragement. iv INTRODUCTION This thesis has been a long time in coming, and was first conceived close to a year and a half before the current date. -

… … Mushi Production

1948 1960 1961 1962 1963 1964 1965 1966 1967 1968 1969 1970 1971 1972 1973 1974 1975 1976 1977 1978 1979 1980 1981 1982 1983 1984 1985 1986 1987 1988 1989 1990 1991 1992 1993 1994 1995 1996 1997 1998 1999 2000 2001 2002 2003 2004 2005 2006 2007 2008 2009 2010 2011 2012 2013 2014 2015 2016 2017 … Mushi Production (ancien) † / 1961 – 1973 Tezuka Productions / 1968 – Group TAC † / 1968 – 2010 Satelight / 1995 – GoHands / 2008 – 8-Bit / 2008 – Diomédéa / 2005 – Sunrise / 1971 – Deen / 1975 – Studio Kuma / 1977 – Studio Matrix / 2000 – Studio Dub / 1983 – Studio Takuranke / 1987 – Studio Gazelle / 1993 – Bones / 1998 – Kinema Citrus / 2008 – Lay-Duce / 2013 – Manglobe † / 2002 – 2015 Studio Bridge / 2007 – Bandai Namco Pictures / 2015 – Madhouse / 1972 – Triangle Staff † / 1987 – 2000 Studio Palm / 1999 – A.C.G.T. / 2000 – Nomad / 2003 – Studio Chizu / 2011 – MAPPA / 2011 – Studio Uni / 1972 – Tsuchida Pro † / 1976 – 1986 Studio Hibari / 1979 – Larx Entertainment / 2006 – Project No.9 / 2009 – Lerche / 2011 – Studio Fantasia / 1983 – 2016 Chaos Project / 1995 – Studio Comet / 1986 – Nakamura Production / 1974 – Shaft / 1975 – Studio Live / 1976 – Mushi Production (nouveau) / 1977 – A.P.P.P. / 1984 – Imagin / 1992 – Kyoto Animation / 1985 – Animation Do / 2000 – Ordet / 2007 – Mushi production 1948 1960 1961 1962 1963 1964 1965 1966 1967 1968 1969 1970 1971 1972 1973 1974 1975 1976 1977 1978 1979 1980 1981 1982 1983 1984 1985 1986 1987 1988 1989 1990 1991 1992 1993 1994 1995 1996 1997 1998 1999 2000 2001 2002 2003 2004 2005 2006 2007 2008 2009 2010 2011 2012 2013 2014 2015 2016 2017 … 1948 1960 1961 1962 1963 1964 1965 1966 1967 1968 1969 1970 1971 1972 1973 1974 1975 1976 1977 1978 1979 1980 1981 1982 1983 1984 1985 1986 1987 1988 1989 1990 1991 1992 1993 1994 1995 1996 1997 1998 1999 2000 2001 2002 2003 2004 2005 2006 2007 2008 2009 2010 2011 2012 2013 2014 2015 2016 2017 … Tatsunoko Production / 1962 – Ashi Production >> Production Reed / 1975 – Studio Plum / 1996/97 (?) – Actas / 1998 – I Move (アイムーヴ) / 2000 – Kaname Prod. -

Kumoricon-2017-Program Book.Pdf

Start your 14-day free trial at funimation.com/subscribe TM Stream Anime. Anytime. Anywhere. TABLE OF CONTENTS Letter from the Chair . 4 Hours of Operation . 5 Guests of Honor . 6 Art Show and Charity Auction . 10 DJ Profi les . 12 Programming . 14 Main Events . 14 Guest Programming . ........................... 15 Industry Programmingg . .................... 20 Anime Music Videoseos . 21 Cosplay . ........................................................... .......................... ........... 22 Karaoke . ............................................................... ...................... .................. 22 Dance Lessons .................... ........................................................ ........................ 24 GeneralralProgramming...................................................... Programmingramming........... .......................... 25 Conventionntion MapsMaps........... ... ..................................... ..................... 30 Chibibi RRoomm . 39 Writing/Artting/Artt......... ................................................................ ....... ................................. 40 Craft s......................................................................s . ......... .......... .... ................................ 41 Videoeo Gaminging... .......................................................... ............... .... ................................ 41 Tabletopetop Gamingaming . .......................................................... .............. ..... ..................... 42 Board andCardGaming....................................................and -

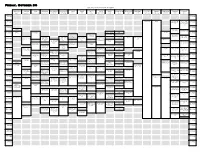

Kumoricon Schedule

Friday, October 26 Generated on Oct 27, 2018, at 8:36pm Main Events Coliseum Arena Auditorium Live Events 1 Live Events 2 Panel 1 Panel 2 Panel 3 Panel 4 Panel 5 Escape Room Workshop 1 Workshop 2 Manga Library Karaoke Chibi Room Viewing 1 Viewing 2 Hall A1 Oregon Ballroom Oregon Ballroom 202 Oregon Ballroom 201 B115-B116 B113-B114 A106 C123 C124 B111-B112 B118 A109 A105 B117 A107-A108 A103-A104 C121-C122 B119 B110 203/204 7:00am 7:00am Open Reading Open Mic Sakura Wars: The Oblivion Island: 8:00am Movie (dub) (TV- Haruka and the 8:00am 14) Magic Mirror (dub) (G) 9:00am 9:00am Seating Pumpkin Scissors (dub) (TV-14) Hal (dub) (TV-14) Phantomhive Dinner by Cloudy Opening Dance Lesson – Panelist Meeting Shenanigans Coloring 10:00am Ceremonies Cha-Cha 10:00am Surviving the The Cosplay Anime: A Television Trickster Soul Eater Not! Shopping Frenzy: Survival Guide (dub) (TV-14) Romeo × Juliet Japan's Manga Vendor Hall 101s Pattern Modification Phantomhive Dinner by Cloudy (dub) (TV-PG) Dance Lesson – Samezuka Cultural Why Anime and Shenanigans Dolly Making Break That Writer's 11:00am Magazines: Where 11:00am Single Time Swing Festival – A Free! and Garment Fitting Manga Studies? Block! Promise Bracelets Your Manga Gets Panel Basics (KAMS Roundtable) Started! Super Nerds: A My Parent's Guide to Hero Academia Anime Le Chevalier D'Eon Alderamin on the Panel!! Phantomhive Dinner by Cloudy (dub) (TV-14) Sky (dub) (TV-14) Dance Lesson – How to Teach Introduction to Shenanigans 12:00pm American Tango Yourself Japanese Sewing 12:00pm Sentai Filmworks -

Traditions and Transformations May 19-May 22, 2019

2019 TAASA Annual Conference Traditions and Transformations May 19-May 22, 2019 Wyndam San Antonio Riverwalk San Antonio, TX TRADITIONS AND TRANSFORMATIONS BIENVENIDOS! WELCOME! We’re excited you’re joining us over the next three days as we begin the journey of bravely and critically embracing change and growth in the work we do in our programs and the services we provide to survivors of sexual violence. In this conference we set out to examine and explore the significance, practice and intersections of Traditions and Transformations in the anti-sexual violence movement, and understand why it’s important to centralize experiences of survivors in these contexts. We also wish to acknowledge that justice and healing come in many forms and that traditions can often perpetuate social structures and institutions that limit culture change in our movement and the systems we work in. Let’s come together this week in meaningful dialogue about the ways in which we have structured our responses to sexual violence and lovingly challenge ourselves to explore new ways of collaboration, connection and community healing. This year we are proud to bring together 49 workshops and two keynote sessions representing the experience and knowledge of 87 presenters. We hope with each breakout you will find a variety of workshops to create opportunities for connection and reflection in your work. We also hope you will find opportunities to explore and enjoy the rich culture and traditions of our host city San Antonio! San Antonio is steeped in a 300-year history that embraces its diverse culture, rich traditions and welcoming spirit. -

Neon Genesis Evangelion: 14 Free

FREE NEON GENESIS EVANGELION: 14 PDF Yoshiyuki Sadamato | 184 pages | 12 Mar 2015 | Viz Media, Subs. of Shogakukan Inc | 9781421578354 | English | San Francisco, United States Neon Genesis Evangelion - Wikipedia Shinji, furious at his father for the orders given in the previous Neon Genesis Evangelion: 14, resigns from NERV. But as an Angel lays waste to the Neon Genesis Evangelion: 14 and the other Evangelions, he begins Neon Genesis Evangelion: 14 reconsider his hasty The activation of EVA goes awry when an Angel takes control of the unit. With EVA itself re-designated as an Angel, Shinji is faced with the moral dilemma of terminating the rogue Evangelion at A bizarre Angel possessing a spherical shadow in the air and a Dirac sea-type body on the ground absorbs Shinji and EVA Looking for a movie the entire family can enjoy? Check out our picks for family friendly movies movies that transcend all ages. For even more, visit our Family Entertainment Guide. See the full list. Title: Neon Genesis Evangelion — When the Angels start attacking the planet Earth in the yearonly a handful of year-old EVA pilots are able to stop them. Written by Chris Cleveland. What can I say about the most perfect anime ever created? What can I say about Shinji, the most complex character ever created? Evangelion begins like an action sci-fi anime, like Akira. It has everything: humor, drama, action, great soundtrack. Great fun! But then you watch episode The 3 last episodes are the most perfect writen anime episodes ever. Yeah, some people don't understand it. -

Adeptus Evangelion, and Not a Game Master, Look No Further! This Chapter, and Indeed This Entire Book, Is Intended Only for Game Masters

We do not own Evangelion™, Dark Heresy™, Warhammer 40K™, or any other intellectual property to be found within this work in any way. We do not claim ownership of any of the art that appears in this work. Instead, all credit regarding the art should go to the artists of Gainax, or the artists listed below. This work is not to be distributed for money to anyone under any circumstances. However, while we may not be able to claim ownership, it would be unfair to refuse to give credit where credit is due to the following: CREDITS Project Coordination: Black Mesa Janitor (RHM), Elpizo (Sachiel) Development and Playtesting: Blast Artists: Writing and Editing: ClamPaste Anonymous Anonymous Feldion (RPSS) bluewine Blast HLeviathan (GRGR III) Drawfag X-09 !W7.CkkM01U CapnKeene Karada Guardsman Harry Dr. Baron Von Evil Satan CapnKeene Jebus (8546514) Dial J. S. Cervini Feldion (RPSS) Mr_Rage LDT-A (RHK) Gilgamesh, King of Heroes Latooni Mastermind Omega !EnkiduOJiw!!fXOkC1tdv81 LawfulNice vendredi Jebus LDT-A (RHK) Vincent “Siege” Angerossa Kamen macrophage Karada Mastemind Omega Special Thanks: Mari Touhou Homebrew Guy Anonymous Masocristy (OlympusMons) Archivist Mordegald Zhuren You, for your continued Protagonist support. Sorain Highwind Yue ZZEva Table of Contents Weaving a Story 1 Anomalous Materials 33 Setting and Tone 2 Unique Armory Contents 33 Keeping your Players Interested 2 Experimental N2 Reactor 33 Mood and Lethality 3 Cold Blooded 34 Extra Material 4 Free Range Evangelions 34 Pacing your Stride 4 Fly me to the Moon 35 In Conclusion -

A Strange Pilot

A strange pilot By Daisy89 Submitted: June 1, 2006 Updated: September 12, 2007 This story is about a strange pilot who arrives in tokyo-3 to be a pilot of unit 04.But something is strange about him. Provided by Fanart Central. http://www.fanart-central.net/stories/user/Daisy89/34344/A-strange-pilot Chapter 1 - The pilot's arrival 3 Chapter 2 - The angel attacks 4 Chapter 3 - Eva pilot of unit 1? 5 Chapter 4 - Showdown between angel and eva part 6 1 Chapter 5 - Showdown between angel and eva part 7 2 Chapter 6 - Doctor's order 8 Chapter 7 - A drunk guardian 9 Chapter 8 - Misato's new roommate 11 Chapter 9 - A new day 13 Chapter 10 - Father and son meet. 15 Chapter 11 - Testing part 1 17 Chapter 12 - Testing part 2 20 Chapter 13 - New angel 22 Chapter 14 - Her desire. 25 Chapter 15 - Another roomate for misato 27 Chapter 16 - Eva info 29 Chapter 17 - Eva's v.s Eva 31 Chapter 18 - Secrets 33 Chapter 19 - School day and angel attack 35 Chapter 20 - Shamshel's defeat 37 Chapter 21 - Runaway's 39 Chapter 22 - Ramiel's assault part 1 41 Chapter 23 - Ramiel's assault part 2 44 Chapter 24 - Ramiel's assault part 3 46 Chapter 25 - Unit 4's upgrade part 1 49 Chapter 26 - Unit 4's upgrade part 2 53 Chapter 27 - Misato in trouble 57 Chapter 28 - Jet Alone 60 Chapter 29 - Meet Asuka Langely Soryu 65 Chapter 30 - Unit 2 activate part 1 69 Chapter 31 - Unit 02 activate part 2 71 Chapter 32 - Angels split personality 75 Chapter 33 - The fourth child's story 81 Chapter 34 - A hot struggle 83 Chapter 35 - Justin's secret Exposed Part1 88 Chapter 36 - Justin's secret Exsposed Part 2 91 1 - The pilot's arrival We begin as an american boy is being flown over to japan along with unit 04.Justin:Hmph.So i got chosen to be a pilot of this machine.It''s interesting knowing that they dont know who i really am.Who i really am will be revealed as soon as the angels are beaten and the human instrumentality almost begins.For i am the 19th angel known as ralile,the angel of destruction.They wont know what hit them,He,he,he.The plane continues to japan. -

Neon Genesis Evangelion Free Ebook

FREENEON GENESIS EVANGELION EBOOK Yoshiyuki Sadamoto | 176 pages | 05 May 2004 | Viz Media, Subs. of Shogakukan Inc | 9781591163909 | English | San Francisco, United States Neon Genesis Evangelion Wiki New Century Evangelioncommonly referred to as Neon Genesis Evangelionis a Japanese anime series, created by Gainaxthat began in October It gained international renown and won several animation awards, and was the start of the Neon Genesis Evangelion series. The term "Evangelion" is in relation to the ancient Greek term for "good messenger" or "good news". The name was chosen in part for its religious symbolism, as well as for the fact that Hideaki Anno said he liked the word "Evangelion" because it "sound[ed] complicated". The Evangelion series revolves around the organization NERV, using large mechas called Evangelions to combat monstrous beings called Angels. While the initial episodes focus largely on religious symbols and specific references to the Bible, the later episodes tend to go deeper into the psyches of the characters, where it is learned that many of them have deep-seated emotional and mental issues. Through the exploration of these issues, the show begins to question reality and the existences therein. Much of the series's content was based on Hideaki Anno's own clinical depression. The story of Neon Genesis Evangelion primarily begins in with the " Second Impact ", a global cataclysm which almost completely destroyed Antarctica and led to the deaths of half the human population of Earth. The Impact is believed by the public at large and even most of NERV to have been the impact of a meteorite landing in Antarctica, causing devastating tsunamis and a change in the Earth's axial tilt leading to global climate change and subsequent geopolitical unrest, nuclear war such as the nuking of Tokyoand general economic distress.