“Popery and Tyranny”: King George III As a Late Stuart

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

George Stanley Faber: No Popery and Prophecy

GEORGE STANLEY FABER: NO POPERY AND PROPHECY BY S.W. GILLEY Durham "Defoe says, that there were a hundred thousand stout country fellows in his time ready to fight to the death against popery, without knowing whether popery was a man or a horse". 1 Such anti-Cath olicism has been a central strand in English culture since the Refor mation, a prejudice "into which we English are born, as into the fall of Adam", 2 as part of a nationalist assertion of the virtues of Protestant Britannia against its Popish enemies, France and Spain, and as the very heart of an English epic of liberation from Rome in the six teenth century. The story needed a villain, as Jack needed a giant; and what better villain than Giant Pope? The fires of Smithfield were burnt into the popular mind by George Foxe's Acts and Mouments, commonly called his Book if Marryrs, the most widely read of all works after the Bible, and the British epic identified Romanism with continental despotism and tyranny, with poverty and wooden shoes, so that the Reformation became the mother of English enlighten ment and liberty.3 Anti-Catholicism had a continuous history from 1520, and in the eighteenth century was an essential part in the definition of British nationhood.4 Its passions among the quality, however, abated some- I W. Hazlitt, Sketches and Essays and Winterslow (London, 1912), p. 71. 2 Henry Edward Cardinal Manning, cited in J. Pereiro, Cardinal Manning: an Intellectual Biography (Oxford, 1998), p. 174. 3 For a survey, see P.B. -

Heritage Library News, Winter 2008

Volume XI Issue 4 Winter 2008 Heritage Library News BIRDIES FOR CHARITY TIME Sign up now! INAUGURAL FESTIVAL WINDS UP WITH A BANG The Library finished its tenth anniversary year with a festival at Historic It’s Birdies For Charity time and Honey Horn in early October celebrating not just our library’s accomplishments we have been invited to take part since its founding in 1997, but more importantly the history of the Island and the again this year. We ask you to diverse cultures and heritage of its residents and visitors. By all accounts it was please use the form included in this greeted with great enthusiasm by those attending the Sunday Afternoon newsletter and pledge One Cent or more for every birdie scored in the festivities under the 2008 Verizon Heritage golf tourna- live oaks and on the ment to be played on The Harbour fields of Historic Town Links April 14th thru 20th. If Honey Horn. you would rather, you may pledge a The audience, fixed amount. modest but enthusi- The Heritage Classic Founda- astic, thrilled to the tion, which runs the tournament, demonstrations of sets aside approximately $100,000 military contingents from tournament distributions to representing the charity and distributes it among the Revolutionary and Birdies for Charity participants ac- Civil War periods in cording to the funds each group our history. They raises. We realized $4,354.64 last cheered on the danc- year.—$3,094.29 pledged by 41 ers and singers from (Continued on page 2) the Hilton Head Sounds of the Civil War—Ten Pound Parrot Gun in Action School for the Arts, the Barbershoppers, and the Step- Inside This Issue ANNUAL MEETING NOTICE pin’ Stones Band. -

The Battle of Ridgefield: April 27, 1777

American Revolution & Colonial Life Programs Pre and Post Lesson Plans & Activities The Battle of Ridgefield: April 27, 1777 • The Battle of Ridgefield was the only inland battle fought in Connecticut during the Revolutionary War. • Captain Benedict Arnold was the main commander for the battle as the British marched upon a weak Colonial Army. Arnold's defenses kept the British at bay until the larger army could come later. • Brigadier General Gold Selleck Silliman of Fairfield was also involved in the battle. In the primary source letter below, he sends word to General Wooster that they need reinforcements. • Silliman’s 2nd wife, Mary Silliman, writes to her parents after the battle, relieved that her husband and son were unharmed. Although her parents are only a few towns away, she is unable to travel the distance. • Another primary source is a silhouette of Lieutenant Colonel Abraham Gould of Fairfield, who died during the battle. At the Fairfield Museum: • Students will view a painted portrait of Mary Silliman in the galleries. • Students will see the grave marker for General Gold Selleck Silliman, his first wife, and a few of his children. • Students will also see the grave marker of Lieutenant Colonel Abraham Gould. Fairfield Museum & History Center | Fairfieldhistory.org | American Revolution: The Battle of Ridgefield A brief synopsis – The Battle of Fairfield: General Tryon of the British army thought that he would be warmly received by the people of Ridgefield after taking out a Colonial supply post just days earlier. Tryon, to his dismay, learned that the town was being barricaded by none other than General Benedict Arnold. -

John Carroll and the Origins of an American Catholic Church, 1783–1815 Author(S): Catherine O’Donnell Source: the William and Mary Quarterly, Vol

John Carroll and the Origins of an American Catholic Church, 1783–1815 Author(s): Catherine O’Donnell Source: The William and Mary Quarterly, Vol. 68, No. 1 (January 2011), pp. 101-126 Published by: Omohundro Institute of Early American History and Culture Stable URL: https://www.jstor.org/stable/10.5309/willmaryquar.68.1.0101 Accessed: 17-10-2018 15:23 UTC JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact [email protected]. Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at https://about.jstor.org/terms Omohundro Institute of Early American History and Culture is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to The William and Mary Quarterly This content downloaded from 134.198.197.121 on Wed, 17 Oct 2018 15:23:24 UTC All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms 101 John Carroll and the Origins of an American Catholic Church, 1783–1815 Catherine O’Donnell n 1806 Baltimoreans saw ground broken for the first cathedral in the United States. John Carroll, consecrated as the nation’s first Catholic Ibishop in 1790, had commissioned Capitol architect Benjamin Latrobe and worked with him on the building’s design. They planned a neoclassi- cal brick facade and an interior with the cruciform shape, nave, narthex, and chorus of a European cathedral. -

The Restoration of the Roman Catholic Hierarchy in England 1850: a Catholic Position

University of Windsor Scholarship at UWindsor Electronic Theses and Dissertations Theses, Dissertations, and Major Papers 1-1-1958 The restoration of the Roman Catholic hierarchy in England 1850: A Catholic position. Eddi Chittaro University of Windsor Follow this and additional works at: https://scholar.uwindsor.ca/etd Recommended Citation Chittaro, Eddi, "The restoration of the Roman Catholic hierarchy in England 1850: A Catholic position." (1958). Electronic Theses and Dissertations. 6283. https://scholar.uwindsor.ca/etd/6283 This online database contains the full-text of PhD dissertations and Masters’ theses of University of Windsor students from 1954 forward. These documents are made available for personal study and research purposes only, in accordance with the Canadian Copyright Act and the Creative Commons license—CC BY-NC-ND (Attribution, Non-Commercial, No Derivative Works). Under this license, works must always be attributed to the copyright holder (original author), cannot be used for any commercial purposes, and may not be altered. Any other use would require the permission of the copyright holder. Students may inquire about withdrawing their dissertation and/or thesis from this database. For additional inquiries, please contact the repository administrator via email ([email protected]) or by telephone at 519-253-3000ext. 3208. THE RESTORATION OF THE ROMAN CATHOLIC HIERARCHY IN ENGLAND ^ 1850 1 A CATHOLIC POSITION Submitted to the Department of History of Assumption University of Windsor in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts. by Eddi Chittaro, B.A* Faculty of Graduate Studies 1 9 5 8 Reproduced with permission of the copyright owner. -

TOURS 1. Ethan Allen: the Green Mountain Boys and the Arsenal

TOURS 1. Ethan Allen: The Green Mountain Boys and the Arsenal of the Revolution When the Green Mountain Boys—many of them Connecticut natives—heard about the Battles of Lexington and Concord, they jumped at the chance to attack the British Fort Ticonderoga in the despised state of New York. • Biographies o Benjamin Tallmadge (codename John Bolton) and the Culper Spy Ring o William Franklin, Loyalist Son of Benjamin Franklin o Seth Warner Leader of the Green Mountain Boys 2. Danbury Raid and the Forgotten General The British think they can land at the mouth of the Saugatuck River on Long Island Sound, rush inland, and destroy the Patriot’s supply depot in Danbury. They succeed, but at great cost thanks to the leadership of Benedict Arnold and General David Wooster. • Biographies o Sybil Ludington, the “Female Paul Revere” o Major General David Wooster o British General William Tyron 3. Israel Putnam and the Escape at Horse Neck Many of the most important military leaders of the American Revolution fought in the French and Indian War. Follow the life and exploits of one of those old veterans, Israel Putnam, as he leads his green Connecticut farmers against the mightiest military in the world. • Biographies and Boxes o General David Waterbury Jr. and Fort Stamford o The Winter Encampment at Redding, 1778-1779 o General David Humphreys o Loyalist Provincial Corp: Connecticut Tories 4. Side Tour: Farmer Put and the Wolf Den In 1742 Israel Putnam’s legend may have started when he killed the last wolf in Connecticut. © 2012 BICYCLETOURS.COM 5. -

THE COMMON-SENSE ARGUMENT for PAPAL INFALLIBILITY SANDRA YOCUM MIZE University of Dayton

Theological Studies 57 (1996) THE COMMON-SENSE ARGUMENT FOR PAPAL INFALLIBILITY SANDRA YOCUM MIZE University of Dayton MERICAN CATHOLIC apologists of the 19th century argued publicly A for the special place of the Petrine office, affirming papal primacy both of honor and jurisdiction. The successor of Peter served as the final arbiter in controversies over the practical applications of the divine law. Many also highlighted his role as vicar of Christ, the visible manifestation of the Church's spiritual source of authority. After the declaration of infallibility at Vatican I, these same apologists publicly defended as theologically reasonable the infallibility of Peter's succes sor, Christ's earthly vicar. These positions are well known. What has not been so clearly recognized is the way in which the presuppositions of the 19th-century American intellectual scene shaped the American Catholic defense of papal infallibility. The common intel lectual assumptions had their source in Scottish "common sense" real ism, the nation's vernacular philosophy that shaped a variety of public discourses including those of religious apologists. Indeed, at the conser vative end of the broad spectrum of American religious thought, com mon-sense affirmations of an infallible religious authority predomi nated. The very influential Princeton theologians, even as they decried an infallible pope, still insisted upon the existence of an infallible religious authority, i.e. Scripture.1 Their arguments were rooted in the common sense that such authority was the necessary condition for faith. The point of this article is to show that the distinctive discourse of American Catholic apologetics grew out of the same root. -

The Dilemma of Anti-Catholicism in American Travel Writing, Circa 1790-1830

The Dilemma of Anti-Catholicism in American Travel Writing, circa 1790-1830 Daniel Kilbride John Carroll University The decades between 1790 and 1830 have rightly been seen as a lull between the anti- Catholic heights of the colonial and antebellum periods. The French alliance, the imperative of religious pluralism and civility under the Bill of Rights, and the small number of Catholics residing in the United States all conspired to reduce popular intolerance toward Catholics in the post-Revolutionary period – although it needs to be recognized that anti-Catholicism remained an respectable form of prejudice throughout this era. In this paper I want to show how American travelers in Europe contributed to the early national reassessment of Roman Catholicism. Travelers enjoyed enhanced credibility because of their first-hand experience in continental Europe. They reinforced some existing prejudices, such as the danger posed by the close relationship between the Church and European despotisms. In other ways they undermined prejudices and introduced new, more positive ways to assess Catholicism. They reaffirmed the historical connection between American culture and sacred art and architecture. They also reassessed traditional notions of Catholic ritual and piety, which Americans had traditionally derided as little better than superstition. Some travelers went beyond recognizing Catholic practice as a legitimate form of Christianity. In a sharp departure from convention, they articulated a kind of envy, arguing that Catholic ritual was in some ways superior, more genuine, than American Protestant practice. Finally, I want to show how these tentative, preliminary assessments informed American attitudes to Catholicism in the antebellum period. After 1830 anti-Catholicism did acquire a new breadth and intensity, and some travelers contributed to this trend. -

Watson's Magazine

THE JEFFERSONIAN PAGE SEVEN The Italian Pope Assaulting Those who maintain the liberty of the press. Nice, readable article on “The Value of Encyclical Pope Letter of Gregory XVI., in 1831, Muzzling”, and we know six Your Liberties. and of Pope Pius IX., in 18 64. at least people Or the liberty of conscience and of worship. we would like to demonstrate said value on. DETWEEN the Law of this Republic and Encyclical of Pius IX., December 8, 1864. + 4- + the Law of Popery, there is a vital con- Or the liberty of speech. “Syllabus” of March Bessemer, Alabama, is for preparedness; flict which cannot be which 18, 18 61. Prop. Ixxix. Encyclical of Pope Pius the birth-place reconciled, and is IX.. December 8, 1864. Bessemer is of Bessemer steel; rapidly producing in this country the condi- Or who contend that papal judgments and de- any brand of preparedness calls for steel, and tions which precede civil war. crees may, without sin, be disobeyed, or differed a lot of it—and there you are. Let no man deceive himself: let every man from, unless they treat of the rules (dogmata) of 4" 4- + faith and morals. Ibid. Just between us and a concrete post, would see the facts, as they are. Or who assign to the State the power of defining The Constitution of the United States de- the civil rights (jura) and province of the church. you mind telling just what the Legislative clares that Congress shall have no power to “Syllabus” of Pope Pius IX., March 8, 1861. -

Battle of Ridgefield - Wikipedia

Battle of Ridgefield - Wikipedia https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Battle_of_Ridgefield Coordinates: 41°18′19″N 73°30′5″W The Battle of Ridgefield was a battle and a series of Battle of Ridgefield skirmishes between American and British forces during the American Revolutionary War. The main battle was fought in Part of the American Revolutionary War the village of Ridgefield, Connecticut, on April 27, 1777. More skirmishing occurred the next day between Ridgefield and the coastline near Westport, Connecticut. On April 25, 1777, a British force landed between Fairfield and Norwalk (now Westport) under the command of New York's Royal Governor Major General William Tryon. They marched to Danbury, where they destroyed Continental Army supplies after chasing off a small garrison of troops. Word spread concerning the British troop movements, and Connecticut militia leaders sprang into action. Major General David Wooster, Brigadier General Gold Selleck Silliman, and Brigadier General Benedict Arnold raised a combined force of roughly 700 Continental Army regular and irregular local militia forces to oppose the raiders, but they could not reach Danbury in time to prevent the destruction of the supplies. Instead, they set out to harass the British on their return to the coast. The company led by General Wooster twice attacked Tryon's Monument to David Wooster in Danbury, rear guard during their march south on April 27. Wooster was Connecticut mortally wounded in the second encounter, and he died five days later. The main encounter then took place at Ridgefield, Date April 27, 1777 where several hundred militia under Arnold's command Location Ridgefield, Connecticut and confronted the British; they were driven away in a running present-day Westport battle down the town's main street, but not before inflicting casualties on the British. -

Ecticut Tercentenary Celebration

ecticut Tercentenary Celebration DANBURY- BETHEL Settled in 1685 f<ww •» OkO PRutS-. September 15 to 21, 1935 PRICE 25c. L , . t • • n- i IV • ^ J -JRIBBB p , tfl HHLraJL* •HI i '; £w lifts •M ali MM • • • V: , « J- N T - * - I* ' ' ' ' ? ^ , • '' >- M m 4 . » iiiii iiillli ...,• . x' ... .>»«'....,... .. ^ i - ..,',.«_.....,...' m ills iliSflll ilif t V L 3 , - , I I M •• 1 H f| • SKI V r I 7 > ' j? ! > J 1 •i Ht 111 1, „ , „fr^ ' : / .'-aPhis -•'•"••"•-".."SHS i'S* . if « " •: i '* :' : f tf SS . .1 .... ..... , ... : If. f * ® IS • • - ' ' .-'.. '..... a : 5 •• . Si® • • ' : •^^tMkm&mBMmmS i • ' i ' ''i^riii "mi r J j;,' ,*>Im 1 ' SSSSSfSlStS fmiMimm i^Sf- B •i : . iM < : %' B • *' ' \< • J ' • si«8i I BPPPB^^^T^ mf > • ' . - • ..<•.'•-' SC. iiiuii iimm^MS^Mi'^31 / :-i--i[.if.h • S ' . • " if^BiiiiiJ- ' ... - 'f •• I . Ill saiff-a; - lili Connecticut State Libran 3 0231 00061 1256 The Connecticut Tercentenary 1635 1935 and The Two Hundred and Fiftieth Anniversary of the Settlement of the Town of Danbury which included the Society of Bethel 1685 1935 A Short Historical Sketch of the Early Days of Both Towns Program of Events for the Tercentennial Celebration -f-Jlf PUBLISHED BY THE TERCENTENARY COMMITTEE PROGRAM SUNDAY, SEPT. 15TH Observance of the Tercentennial by all the Churches separately at the usual services. 4 p.m. Floats Parade. 7 p.m. Outdoor Union Service of All Churches Corner Deer Hill Avenue and Wooster Street. MONDAY, SEPT. 16TH 8 p.m. Colonial Ball, Elks Auditorium. WEDNESDAY, SEPT. 17TH 8 p.m. Tercentenary Concert, Empress Theatre. FRIDAY AND SATURDAY, SEPT. -

Event Program

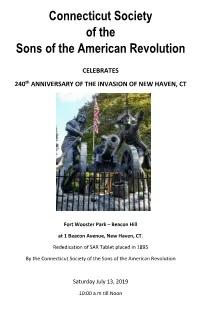

Connecticut Society of the Sons of the American Revolution CELEBRATES 240th ANNIVERSARY OF THE INVASION OF NEW HAVEN, CT Fort Wooster Park – Beacon Hill at 1 Beacon Avenue, New Haven, CT. Rededication of SAR Tablet placed in 1895 By the Connecticut Society of the Sons of the American Revolution Saturday July 13, 2019 10:00 a.m till Noon Introductions President of the Connecticut Society of the SAR Damien Cregeau Commander of the Connecticut Line David Perkins Commander 2nd Company Governor’s Foot Guard Richard Greenwalch Past Grand Marshall of the Connecticut Masons Marshall Robinson Honorable Mayor of New Haven Toni Harp Co-Chairman of the Friends of Wooster Park Susan Marchese State Regent of the Daughters of the American Revolution Christly Hendrie The Connecticut 6th Regiment Rick Shreiner Yale Veterans Liaison Jack Beecher Executive Director of the New Haven Museum Margaret Tockarshewsky Past State Troubadour Thomas Callinan 2nd Company Governors Horse Guard Steven Chapman Program Posting of the colors The Connecticut Line, 2nd Company Foot Guard, 6th Connecticut Regiment Invocation Heavenly Father, we are here today to cherish the memories of the patriots, a little militia company with muskets and a small cannon who fought a valiant resistance against British soldiers and mercenaries. We are standing on the battlefield that was once filled with smoke and carnage. This conflict gave new life and vigor to the very spirit that it aimed to quelch. This battle and similar battles against overwhelming forces help to forge the liberty and freedom we enjoy today in the United States of America. Through Jesus Christ our Lord, Amen.