Filmmaker Labor in Collaborating and Co-Creating with Audiences

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Fan/Creator Alliance: Social Media, Audience Mandates, and the Rebalancing of Power in Studio–Showrunner Disputes

Media Industries 5.2 (2018) The Fan/Creator Alliance: Social Media, Audience Mandates, and the Rebalancing of Power in Studio–Showrunner Disputes Annemarie Navar-Gill1 UNIVERSITY OF MICHIGAN amngill [AT] umich.edu Abstract Because companies, not writer-producers, are the legally protected “authors” of television shows, when production disputes between series creators and studio/ network suits arise, executives have every right to separate creators from their intellectual property creations. However, legally disempowered series creators can leverage an audience mandate to gain the upper hand in production disputes. Examining two case studies where an audience mandate was involved in overturning a corporate production decision—Rob Thomas’s seven-year quest to make a Veronica Mars movie and Dan Harmon’s firing from and subsequent rehiring to his position as the showrunner of Community—this article explores how the social media ecosystem around television rebalances power in disputes between creators and the corporate entities that produce and distribute their work. Keywords: Audiences, Authorship, Management, Production, Social Media, Television Scripted television shows have always had writers. For the most part, however, until the post-network era, those writers were not “authors.” As Catherine Fisk and Miranda Banks have shown in their respective historical accounts of the WGA (Writers Guild of America), television writers have a long history of negotiating the terms of what “authorship” meant in the context of their work, but for most of the medium’s history, the cultural validation afforded to an “author” eluded them.2 This began to change, however, in the 1990s, when the term “showrunner” began to appear in television trade press.3 “Showrunner” is an unofficial title referring to the executive producer and head writer of a television series, who acts in effect as the show’s CEO, overseeing the program’s story development and having final authority in essentially all production decisions. -

HP Smart Web Printing

What's on tap this month that executives won't want to miss - USATODAY.com Page 1 of 5 Cars Auto Financing Event Tickets Jobs Real Estate Online Degrees Business Opportunities Shopping Search How do I find it? Subscribe to paper Become a member of the USA Home News Travel Money Sports Life Tech Weather TODAY community now! Log in | Become a member What's this? Money » Executive Suite Weekly Features Company News Company Calendars Annual Reports GET A Enter symbol(s) or Keywords QUOTE: What's on tap this month that executives Related Advertising Links What's This? Obama Is Giving You Money Read How I Got a $12k Check From The Economic… won't want to miss www.ObamasEconomicStimulus.com Updated 7h 49m ago | Comment | Recommend 1 E-mail | Save | Print | CALENDAR $37,383 Stimulus Checks It's Official. The Gov Is Giving Out Billions. I… www.GovGrantFunds.com Monday: The Commerce Department Yahoo! Buzz reports whether consumer spending was up Advertisement at the first of the year after a dismal fourth Digg quarter. Newsvine Reddit MEDIA HAPPENINGS: Watch, listen & read IN MAGAZINES THIS MONTH: Check it out Facebook FIVE QUESTIONS: For ... utility exec David What's this? Ratcliffe WHAT I READ: With eco-friendly exec Jeffrey Hollender CORPORATE PULSE: Executive Suite front page Enlarge By Ron Batzdorff, Starz Original Actors Lizzy Caplan and Adam Scott in an episode of Friday: Did job losses exceed 600,000 last month? The Labor the clever workplace sitcom "Party Down," airing on Department tally tells. Starz. March 8: Daylight Saving Time begins. -

The Izombie Omnibus Online

3x45F [Read free] The iZombie Omnibus Online [3x45F.ebook] The iZombie Omnibus Pdf Free Michael Allred ePub | *DOC | audiobook | ebooks | Download PDF Download Now Free Download Here Download eBook #345496 in Books imusti 2015-12-08 2015-12-08Original language:EnglishPDF # 1 11.20 x 1.70 x 7.60l, .0 #File Name: 1401262031646 pagesDiamond Comics | File size: 51.Mb Michael Allred : The iZombie Omnibus before purchasing it in order to gage whether or not it would be worth my time, and all praised The iZombie Omnibus: 4 of 4 people found the following review helpful. Different than what i was expecting, but still good.By Kindle CustomerI'm a big fan of the t.v. series, so I decided to read the comic it was based on. I like the t.v. series a lot more, but this is still a really good story. Just wish it could have been longer.2 of 2 people found the following review helpful. Grandma says thumbs upBy Betty JeanNot the typical audience for these books (at 68) but I love the TV show and wanted to read the graphic novels. Definitely not disappointed.2 of 2 people found the following review helpful. Exactly what I wanted it to be.By Randolph WallerShipped on time. Nice hardbook edition collected series for any fan. Told from a female zombie's perspective, IZOMBIE is a smart, witty detective series with a mix of urban fantasy and romantic dramedy. Gwendolyn "Gwen" Dylan is a 20-something gravedigger in an eco-friendly cemetery. Once a month she must eat a human brain to keep from losing her memories, but in the process she becomes consumed with the thoughts and personality of the dead person until she eats the next brain. -

DAVID HELFAND, ACE Editor

DAVID HELFAND, ACE Editor PROJECTS DIRECTORS STUDIOS/PRODUCERS YOUNG SHELDON Various Directors WARNER BROS. / CBS Seasons 1 - 5 Chuck Lorre, Steven Molaro Tim Marx UNITED WE FALL Mark Cendrowski ABC / John Amodeo, Julia Gunn Pilot Julius Sharpe UNTITLED REV RUN Don Scardino AMBLIN PARTNERS / ABC Pilot Presentation Jeremy Bronson, Rev Run Simmons Jhoni Marchinko ATYPICAL Michael Patrick Jann SONY / NETFLIX 1 Episode Robia Rashid, Seth Gordon Mary Rohlich, Joanne Toll GREAT NEWS Various Directors UNIVERSAL / NBC Season 1 Tina Fey, Robert Carlock Tracey Wigfield, David Miner THE BRINK Michael Lehman HBO / Roberto Benabib, Jay Roach Season 1 Tim Robbins Jerry Weintraub UNCLE BUCK Reggie Hudlin ABC / Brian Bradley, Steven Cragg Season 1 Ken Whittingham Korin Huggins, Will Packer Fred Goss Franco Bario BAD JUDGE Andrew Fleming NBC / Adam McKay, Kevin Messick Pilot Will Ferrell THE MINDY PROJECT Various Directors FOX / Mindy Kaling, Howard Klein Seasons 1 - 2 Michael Spiller WEEDS Craig Zisk SHOWTIME Series Paul Feig Jenji Kohan, Roberto Benabib 2x Nominated, Single Camera Comedy Paris Barclay Mark Burley Series – Emmys NEXT CALLER Pilot Marc Buckland NBC / Stephen Falk, Marc Buckland PARTY DOWN Bryan Gordon STARZ Season 2 Fred Savage John Enbom, Rob Thomas David Wain Dan Etheridge, Paul Rudd THE MIDDLE Pilot Julie Anne Robinson ABC / DeeAnn Heline, Eileen Heisler GANGSTER’S PARADISE Ralph Ziman Tendeka Matatu Winner, Best Editing, FESPACO Awards FOSTER HALL Bob Berlinger NBC / Christopher Moynihan Pilot Conan O’Brien, Tom Palmer THAT ‘70S SHOW David Trainer FOX Season 6 Jeff Filgo, Jackie Filgo, Tom Carsey Nominated, Multi-Cam Comedy Series – Mary Werner Emmys CRACKING UP Chris Weitz FOX Pilot Paul Weitz Mike White GROSSE POINTE Peyton Reed WARNER BROS. -

Pacific Design Center Hollywood Ca | November 15Th at 6Pm

WE ALL HAVE A VOICE. CELEBRATE IT. 2nd Annual GALA PACIFIC DESIGN CENTER HOLLYWOOD CA | NOVEMBER 15TH AT 6PM © 2015 Society of Voice Arts And Sciences™ HBO proudly To the Voice Arts Community: supports By community, I refer to all the people who collaborate in one form or the SOCIETY OF VOICE another to bring about the work that sustains our livelihoods and sense of ™ accomplishment. The voice arts community is the hub around which we all ARTS & SCIENCES come together. Anything can happen at this intersection and all of us can help determine the outcome. and congratulates We are not simply spectators of the industry, watching it take shape around this year’s nominees us. We are the shapers, actively breathing new life into its ever-changing form. We do this by bringing our best selves to the process with the intention of attending to the work with professionalism, respect, creativity and the spirit of collaboration, so that we may all enjoy gainful employment. I am thrilled to be a part of the magic that is the Voice Arts® Awards. It is an enchanted world of acknowledgment and encouragement and it honors the best in all of us. It is not about being better than someone else. It is about being your best. Tonight we celebrate our esteemed jurors. We celebrate the entrants, nominees and the soon to be named recipients of the top honor. This is our night. Sincerely, Rudy Gaskins Chairman & CEO Society of Voice Arts and Sciences™ ©2015 Home Box Office, Inc. All rights reserved. 3 HBO® and related channels and service marks are the property of Home Box Office, Inc. -

NEW RESUME Current-9(5)

DEEDEE BRADLEY CASTING DIRECTOR [email protected] 818-980-9803 X2 TELEVISION PILOTS * Denotes picked up for series SWITCHED AT BIRTH* One hour pilot for ABC Family 2010 Executive Producers: Lizzy Weiss, Paul Stupin Director: Steve Miner BEING HUMAN* One hour pilot for Muse Ent./SyFy 2010 Executive Producers: Jeremy Carver, Anna Fricke, Michael Prupas Director: Adam Kane UNTITLED JUSTIN ADLER PILOT Half hour pilot for Sony/NBC 2009 Executive Producers: Eric Tannenbaum, Kim Tannenbaum, Mitch Hurwitz, Joe Russo, Anthony Russo, Justin Adler, David Guarascio, Moses Port Directors: Joe Russo and Anthony Russo PARTY DOWN * Half hour pilot for STARZ Network 2008 Executive Producers: Rob Thomas, Paul Rudd Director: Rob Thomas BEVERLY HILLS 90210* One hour pilot for CBS/Paramount and CW Network. Executive Producers: Gabe Sachs, Jeff Judah, Mark Piznarski, Rob Thomas Director: Mark Piznarski MERCY REEF aka AQUAMAN One hour pilot for Warner Bros./CW 2006 Executive Producers: Miles Millar, Al Gough, Greg Beeman Director : Greg Beeman Shared casting..Joanne Koehler VERONICA MARS* One hour pilot for Stu Segall Productions/UPN 2004 Executive Producers: Joel Silver, Rob Thomas Director: Mark Piznarski SAVING JASON Half hour pilot for Warner Bros./WBN 2003 Executive Producer: Winifred Hervey Director: Stan Lathan NEWTON One hour pilot for Warner Bros/UPN 2003 Executive Producers: Joel Silver, Gregory Noveck, Craig Silverstein Director: Lesli Linka Glatter ROCK ME BABY* Half hour pilot for Warner Bros./UPN 2003 Executive Producers: Tony Krantz, Tim Kelleher -

The Humor and Freshness of VERONICA MARS Arrive to HBO

The humor and freshness of VERONICA MARS arrive to HBO Starring Kristen Bell, the fourth season of this fan-favorite series premieres on June 5th, exclusively on HBO and HBO GO MIAMI, FL. May 6th, 2020 – With the fresh and sarcastic humor that characterize her, VERONICA MARS arrives to HBO and HBO GO. Starring Kristen Bell and created by writer Rob Thomas, the fourth season of this series about the clever detective premieres on June 5th. Times per country: Hbocaribbean.com In the fictional coastal community of Neptune, the rich and powerful make the rules and desperately seek to hide their dirty little secrets. Unfortunately for them, Veronica Mars, a brave and intelligent private investigator, is dedicated to solving the most complicated mysteries of this town. Season four begins when young vacationers are killed during spring break, impacting the city's tourism industry, and Mars Investigations is hired by the parents of one of the victims to find the killer. The story will follow Veronica's investigations, which are shrouded in an epic mystery that will lead her to face the powerful elites of the city. The fourth season of VERONICA MARS stars Kristen Bell, alongside Enrico Colantoni and Jason Dohring. The executive producers are Rob Thomas, Diane Ruggiero-Wright, Dan Etheridge, and Kristen Bell. The series is produced by Spondoolie Productions, in association with Warner Bros. Television. Enjoy the fourth season of VERONICA MARS exclusively on HBO and HBO GO starting on June 5th. Posted on 2020/05/06 on hbomaxlapress.com. -

Exploring the Veronica Mars Fan Movement

Bowling Green State University ScholarWorks@BGSU Graduate Communication Association Conference GCA Conference 2015 Mar 27th, 1:00 PM - 1:55 PM Exploring the Veronica Mars Fan Movement Julia E. Largent Bowling Green State University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.bgsu.edu/gca_conf Largent, Julia E., "Exploring the Veronica Mars Fan Movement" (2015). Graduate Communication Association Conference. 3. https://scholarworks.bgsu.edu/gca_conf/GCA2015/Session3/3 This Event is brought to you for free and open access by the Conferences and Events at ScholarWorks@BGSU. It has been accepted for inclusion in Graduate Communication Association Conference by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks@BGSU. Kickstarter is a website used to help creative individuals fund innovative and entrepreneurial ideas including (but not limited to) wallets, music, restaurants, and films. In 2013, 91,585 fans donated $5,702,153 to see the fan-favorite television show, Veronica Mars, become a film. The show, which was cancelled in 2007, aired for three seasons on CBS. In March 2014, the film was released in theaters as well as instantly on various video-on-demand options (later to be released on DVD and Blu-Ray in May 2014). The show and movie is centered on a high-school student-turned-private detective (Veronica Mars) who solves every day minor cases as well as an overarching theme throughout the first season regarding the murder of her best friend. Each season focuses on a main story arch with smaller cases in each episode. The film takes place ten years later and centers on the death of a classmate (who became a famous popstar after high school). -

Vm 2Nd Yellow

NOT FOR SALE. FOR PROMOTIONAL USE ONLY. 5/30/13 (Final White) Rev. 5/30/13 (Blue) Rev. 6/07/13 (Pink) Rev. 6/12/13 (Yellow) Rev. 6/14/13 (Green) Rev. 6/17/13 (Goldenrod) Rev. 6/24/13 (Buff) Rev. 6/30/13 (Salmon) Rev. 7/01/13 (Cherry) Rev. 7/07/13 (Tan) Rev. 7/14/13 (2nd Blue) Rev. 7/29/13 (2nd Pink) Rev. 8/01/13 (2nd Yellow) VERONICA MARS Story by Rob Thomas Screenplay by ALIRob ThomasJARDINE & Diane Ruggiero NOT FOR SALE. FOR PROMOTIONAL USE ONLY. 1 INT. VERONICA AND PIZ’S TINY NYC APARTMENT - DAY 1 WIDE SHOT OF A SMALL ROOM. Dawn light floods in the windows. Veronica, in silhouette, crosses while slipping on a blazer. GAYLE BUCKLEY (V.O.) A year at Hearst College. B.A. in psychology from Stanford. Near the top of your class at Columbia Law. ECU on Veronica buttoning the blazer. GAYLE BUCKLEY (V.O.) An internship with the FBI. That’s unique. ECU on Veronica putting on lipstick. GAYLE BUCKLEY (V.O.) It says here you’re scheduled to take the bar six weeks from now. 2 EXT. NEW YORK STREET - DAY 2 Veronica emerges from an underground New York subway stop. It’s Veronica as we’ve never seen her -- an adult, a professional. GAYLE BUCKLEY (V.O.) A little about us -- we’re a multinational firm with 50 lawyers here in New York. Veronica crosses through an intersection with a sea of New Yorkers. ALI JARDINE GAYLE BUCKLEY (V.O.) Our clients here at Truman-Mann are primarily Fortune 500 companies. -

THE CHRISTMAS HOUSE’ Cast Bios

‘THE CHRISTMAS HOUSE’ Cast Bios ROBERT BUCKLEY (Mike) – Robert Buckley is no stranger to playing the sexy leading man. Known for his role as Clayton ‘Clay’ Evans on one of The CW’s longest airing drama series One Tree Hill, Rob played a brash young sports agent who represented star NBA basketball player Nathan Scott (played by James Lafferty). Rob also starred recently in another hit series on The CW, the Rob Thomas developed DC comic book-based series, iZombie for 5 seasons. A native southern-Californian, Robert grew up in Claremont, California before moving to San Diego to attend the University of California at San Diego (UCSD). After earning a degree in Economics, he spent a year and a half working as an Economic Consultant before throwing in the towel to head off to LA to pursue a career in entertainment. Buckley’s other roles include “Kirby Atwood” on the NBC series Lipstick Jungle opposite Brooke Shields and Kim Raver, as well as a recurring role on the CW comedy Privileged, as magazine Editor in Chief “David Besser.” He also played the successful playwright on ABC’s 666 Park Avenue opposite Vanessa Williams and as Jaime King’s love interest “Peter” on CW’s hit series, Hart of Dixie. Other credits include Flirting with Forty where he starred alongside Heather Locklear playing surfer entrepreneur, “Kyle Hamilton” and The Christmas Contract. Rob will be seen this holiday season in Christmas House which he developed for Hallmark and stars as well as serving as Executive Producer. Rob also has worked as a writer and free-lance producer for E! News. -

Tv Shows - 2019 Drama

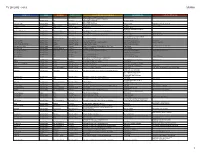

TV SHOWS - 2019 DRAMA SHOW TITLE GENRE NETWORK SEASON STATUS STUDIO / PRODUCTION COMPANIES SHOWRUNNER(S) EXECUTIVE PRODUCERS 68 Whiskey Episodic Drama Paramount Network Ordered to Series CBS TV Studios / Imagine Television Roberto Benabib Fox TV Studios / 20th Century Fox Television, 911 Episodic Drama Fox Renewed Ryan Murphy Productions Timothy P. Minear, 20th Century Fox TV / 9-1-1: Lone Star Episodic Drama Fox Ordered to Series Ryan Murphy Productions Ryan P. Murphy Brad Falchuk; Timothy P. Minear A Million Little Things Episodic Drama ABC Television Renewed ABC Studios / Kapital Entertainment DJ Nash James Griffiths A Teacher Drama FX Network Ordered To Series FX Productions Hannah M. Fidell Jed Whedon; Maurissa Tancharoen; Agents of S.H.I.E.L.D. Episodic Drama ABC Television Renewed ABC Studios / Marvel Entertainment; Mutant Enemy Jeffrey Bell Alive Episodic Drama CBS Entertainment Not Picked Up CBS TV Studios Jason Tracey Robert Doherty All American Episodic Drama CW Network Renewed Warner Bros Television / Berlanti Productions Nkechi Carroll, Gregory G. Berlanti Greg Spottiswood; Leonard Goldstein; All Rise Episodic Drama CBS Entertainment Ordered to Series Warner Bros Television Michael Robin; Gil Garcetti Almost Paradise Episodic Drama WGN America Ordered to Series Electric Entertainment Gary Rosen; Dean Devlin Marc Roskin Amazing Stories Episodic Drama Apple Ordered To Series Universal Television LLC / Amblin Television Adam Horowitz; Edward Kitsis David H. Goodman Amazon/Russo Bros Project Episodic Drama Amazon Ordered To Series Amazon Studios / AGBO Anthony Russo; Joe Russo American Crime Story Episodic Drama FX Network Renewed Fox 21; FX Productions / B2 Entertainment; Color Force Ryan Murphy Brad Falchuk; D V. -

'Best. Show. Ever.': Who Killed Veronica Mars?

JPTV 1 (1) pp. 39–52 Intellect Limited 2013 Journal of Popular Television Volume 1 Number 1 © 2013 Intellect Ltd Article. English language. doi: 10.1386/jptv.1.1.39_1 Matthew PaProth Georgia Gwinnett College ‘Best. Show. ever.’: who killed Veronica Mars? aBStract KeywordS In this article, I argue that Veronica Mars is a fruitful site for critical analysis as Veronica Mars a result of its position between cult and mainstream fandom. As a result of network audience pressure, writer-creator Rob Thomas made significant changes to both the show’s cult television structure and content; simultaneously, he positioned it as a cult-television haven for Buffy the Vampire fans of Buffy the Vampire Slayer, which had recently gone off the air. This deliber- Slayer ate positioning, coupled with Thomas’s openness about the process and the surpris- ing willingness of cult fans to cooperate, makes it a unique case study in the business of popular television. My peeps and I just finished a crazed Veronica Marsathon, and I can 1. CW came about as no longer restrain myself. Best. Show. Ever. Seriously, I’ve never gotten a result of a merger between the owners more wrapped up in a show I wasn’t making, and maybe even more of UPN (Time-Warner) than those. and CBS, with the first letters of CBS and (Joss Whedon, Whedonesque blog, August 2005) Warner joining to form the CW moniker. The Between 2004 and 2007, Veronica Mars (2004–07) aired 64 episodes over first two seasons of Veronica Mars aired three seasons on the United Paramount Network (UPN) and then the CW on UPN, with the third Television Network (CW), a remarkably long run given the incredibly low airing on CW.