Austerity and the Rise of the Nazi Party

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Development and Character of the Nazi Political Machine, 1928-1930, and the Isdap Electoral Breakthrough

Louisiana State University LSU Digital Commons LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses Graduate School 1976 The evelopmeD nt and Character of the Nazi Political Machine, 1928-1930, and the Nsdap Electoral Breakthrough. Thomas Wiles Arafe Jr Louisiana State University and Agricultural & Mechanical College Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_disstheses Recommended Citation Arafe, Thomas Wiles Jr, "The eD velopment and Character of the Nazi Political Machine, 1928-1930, and the Nsdap Electoral Breakthrough." (1976). LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses. 2909. https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_disstheses/2909 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at LSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses by an authorized administrator of LSU Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. INFORMATION TO USERS This material was produced from a microfilm copy of the original document. While the most advanced technological means to photograph and reproduce this document have been used, the quality is heavily dependent upon the quality of the original submitted. « The following explanation of techniques is provided to help you understand markings or patterns which may appear on this reproduction. 1.The sign or "target" for pages apparently lacking from the document photographed is "Missing Page(s)". If it was possible to obtain the missing pega(s) or section, they are spliced into the film along with adjacent pages. This may have necessitated cutting thru an image and duplicating adjacent pages to insure you complete continuity. 2. When an image on the film is obliterated with a large round black mark, it is an indication that the photographer suspected that the copy may have moved during exposure and thus cause a blurred image. -

Records of the Immigration and Naturalization Service, 1891-1957, Record Group 85 New Orleans, Louisiana Crew Lists of Vessels Arriving at New Orleans, LA, 1910-1945

Records of the Immigration and Naturalization Service, 1891-1957, Record Group 85 New Orleans, Louisiana Crew Lists of Vessels Arriving at New Orleans, LA, 1910-1945. T939. 311 rolls. (~A complete list of rolls has been added.) Roll Volumes Dates 1 1-3 January-June, 1910 2 4-5 July-October, 1910 3 6-7 November, 1910-February, 1911 4 8-9 March-June, 1911 5 10-11 July-October, 1911 6 12-13 November, 1911-February, 1912 7 14-15 March-June, 1912 8 16-17 July-October, 1912 9 18-19 November, 1912-February, 1913 10 20-21 March-June, 1913 11 22-23 July-October, 1913 12 24-25 November, 1913-February, 1914 13 26 March-April, 1914 14 27 May-June, 1914 15 28-29 July-October, 1914 16 30-31 November, 1914-February, 1915 17 32 March-April, 1915 18 33 May-June, 1915 19 34-35 July-October, 1915 20 36-37 November, 1915-February, 1916 21 38-39 March-June, 1916 22 40-41 July-October, 1916 23 42-43 November, 1916-February, 1917 24 44 March-April, 1917 25 45 May-June, 1917 26 46 July-August, 1917 27 47 September-October, 1917 28 48 November-December, 1917 29 49-50 Jan. 1-Mar. 15, 1918 30 51-53 Mar. 16-Apr. 30, 1918 31 56-59 June 1-Aug. 15, 1918 32 60-64 Aug. 16-0ct. 31, 1918 33 65-69 Nov. 1', 1918-Jan. 15, 1919 34 70-73 Jan. 16-Mar. 31, 1919 35 74-77 April-May, 1919 36 78-79 June-July, 1919 37 80-81 August-September, 1919 38 82-83 October-November, 1919 39 84-85 December, 1919-January, 1920 40 86-87 February-March, 1920 41 88-89 April-May, 1920 42 90 June, 1920 43 91 July, 1920 44 92 August, 1920 45 93 September, 1920 46 94 October, 1920 47 95-96 November, 1920 48 97-98 December, 1920 49 99-100 Jan. -

Austerity and the Rise of the Nazi Party Gregori Galofré-Vilà, Christopher M

Austerity and the Rise of the Nazi party Gregori Galofré-Vilà, Christopher M. Meissner, Martin McKee, and David Stuckler NBER Working Paper No. 24106 December 2017, Revised in September 2020 JEL No. E6,N1,N14,N44 ABSTRACT We study the link between fiscal austerity and Nazi electoral success. Voting data from a thousand districts and a hundred cities for four elections between 1930 and 1933 shows that areas more affected by austerity (spending cuts and tax increases) had relatively higher vote shares for the Nazi party. We also find that the localities with relatively high austerity experienced relatively high suffering (measured by mortality rates) and these areas’ electorates were more likely to vote for the Nazi party. Our findings are robust to a range of specifications including an instrumental variable strategy and a border-pair policy discontinuity design. Gregori Galofré-Vilà Martin McKee Department of Sociology Department of Health Services Research University of Oxford and Policy Manor Road Building London School of Hygiene Oxford OX1 3UQ & Tropical Medicine United Kingdom 15-17 Tavistock Place [email protected] London WC1H 9SH United Kingdom Christopher M. Meissner [email protected] Department of Economics University of California, Davis David Stuckler One Shields Avenue Università Bocconi Davis, CA 95616 Carlo F. Dondena Centre for Research on and NBER Social Dynamics and Public Policy (Dondena) [email protected] Milan, Italy [email protected] Austerity and the Rise of the Nazi party Gregori Galofr´e-Vil`a Christopher M. Meissner Martin McKee David Stuckler Abstract: We study the link between fiscal austerity and Nazi electoral success. -

Survey of Current Business July 1930

ries^ for thoidiintry as a ^halef instead of for ^gljl ^ eipptooiiii^ or industry which the jrelali^e ip^,^cr^^ tnth tbe base ye^ or ' ^ ^ s^nie manuer $,s in ' (^V > £ -^ T*-/v Vv^^ "?- ^ t^ ; >>^^i v *'-' >mp^t ^t^iee^ She ehar "Rajfio SW (< : k ^\ - >« .^fM%*fxW^!'9^&Ti m '* * - :^^v;vf^^|p!^s*?^l>"y^^ti ^ &; ^ *.. w, ^ - -v ^ '^ ^^S&L'^^wD^' ttfi^^^ i:^%« ^^.i'^v-^^SIf " "" |v-' ,^v .*;-( s£f*jisikMAm of, PJT-- -!i . a*l'; f"i^l. ijrea or |;- • ;^^y*^.m^ ^e§" ' . ,wMfeA0^i^^t^^^^ *• ^ ' ^ r^*t* ' \^* -1^,^^ V*^'"*" <*7 xv v * ^v ^ .^ 7-^ ? -j ; + r : V : : I;" ' v^;,M^\jfi^^^ii^ i '':'•1 ' -T u<' tf '" • ^ !>C 3J^cdB0 ^oos?v r - *-y •" " '• v^ :: J/ • •x '. Sx> - -^; > '* ^j$^^C <^t % ,v , ^ ^t >• "•/ ; • " > ^ ' .*^ v *i^ / ]^f-f\^^^^^^^j^^i!^^yyf^^-jjUK3X»s an*} <>Pfg*yW'» vwjf \JUtiv*Jlfc»JULO -CMS ^oa "S^m^909|^^^ .^fiia^yc^i^^yo^ $*<*' ^,r rMUUJUMLClltJS, XjrUVCAUtiUlDJUU JL JLljJLWJLlS lBt-J^h<Oo%o¥;.B^aa ^wa^s.) !.«y ^ *H* t .x * ^ r * * V-^-rf* ^*" t* '- ''\;P«fi^dto^]ii ,."rcw. *«^A^^«w^^|«^0llt bllSIB^SS v «*V, 4-l«4i ^,rt U A ^*v ^^BM^.^ ^^^^itm^f* ," r0bfeSii§d^&<)lar: '^ WTOto|^aii:^iiff,. i, C"», >^- >^XxwpHiftaJi s-B^^mraiM^'^p^rv^ogicivv v«^p^ni^B ^.' M^ffit; ^i^^ii^^;^f^Vf^jia-fB^^BfC,wpj* ; ^ijro ^ ^^ V ^-^?'K^/r ^? 5-? ^*^r jtaM^Wt^^^^^ f ^>>1,':>^ . ' SURVEY OF CURRENT BUSINESS PUBLISHED BY UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT OF COMMERCE Subscription price of the SURVEY OF CURRENT BUSINESS is ?1.50 a year; single copies (monthly), 10 cents, semiannual issue, 25 cents. -

1930 Congress! on Al Record-House 8683

1930 CONGRESS! ON AL RECORD-HOUSE 8683 CLASS 6 NEBRASKA Donald F. Bigelow. William J. Grace. Herbert M. Hanson, Clay Center. Thomas D. Davis. Stanley Hawks. Andrew E. Stanley, Loomis. Samuel S. Dickson. Stewart E. McMillin. NEW HAMPSHIRE Harold D. Finley. Walter T. Prendergast. Walter A. Foote. Gaston Smith. Harriet A. Reynolds, Kingston. Bernard Gotlieb. Gilbert R. Wilson. NEW YORK CLASS 7 Albert C. Stanton, Atlanta. Maurice W. Altaffer. Harvey Lee Milbourne. Harry L. Carhart, Coeymans. Paul Bowerman. Hugh S. Miller. DeWitt C. Talmage, East Hampton. Paul H. Foster. Julian L. Pinkerton. Clarence F. Dilcher, Elba. Bernard F. Hale. Leland L. Smith. John A. Rapelye, Flushing. John F. Huddleston. Edward B. Thomas. Clarence M. Herrington, Johnsonville. Car] D. Meinhardt. Emma P. Taylor, Mexico. Mason Turner. William V. Horne, Mohegan Lake. CLASS 8 LeRoy Powell, Mount Vernon. Knox Alexander. George F. Kennan. Dana J. Duggan, Niagara University. Vinton Chapin. Gordon P. Merriam. Henry C. Windeknecht, Rensselaer. Prescott Childs. Samuel Reber, jr. NORTH DAKOTA Lewis Clark. Joseph C. Satterthwaite. William M. Gwynn. S. Walter Washington. Ole T. Nelson, Stanley. OHIO PATENT 0:F.FICE Frank Petrus Edinburg to be examiner in chief. Bolivar C. Reber, Loveland. Fred Me'rriam Hopkins to be Assist!lnt Commissioner of Pat Solomon J. Goldsmith, Painesville. ents. OKLA.HOMA. Paul Preston Pierce to be examiner in chief. William C. Yates, Comanche. Elonzo Tell Morgan to be examiner in chief. "' Ben F. Ridge, Duncan. COLLECTORS OF CUSTOMS SOUTH OAROLINA Jeannette A. Hyde, district No. 32, Honolulu, Hawaii. Paul F. W. Waller, Myers. Robert B. Morris, distl'ict No. -

Droughts of 1930-34

UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR Harold L. Ickes, Secretary GEOLOGICAL SURVEY W. C. Mendenhall, Director Water-Supply Paper 680 DROUGHTS OF 1930-34 BY JOHN C. UNITED STATES GOVERNMENT PRINTING OFFICE WASHINGTON : 1936 i'For sale by the Superintendent of Documents, Washington, D. C. Price 20 cents CONTENTS Page Introduction ________ _________-_--_____-_-__---___-__________ 1 Droughts of 1930 and 1931_____._______________________ 5 Causes_____________________________________________________ 6 Precipitation. ____________________________________________ 6 Temperature ____________-_----_--_-_---___-_-_-_-_---_-_- 11 Wind.._.. _ 11 Effect on ground and surface water____________________________ 11 General effect___________________________________________ 11 Ground water___________________________ _ _____________ _ 22 Surface water___________________________________________ 26 Damage___ _-___---_-_------------__---------___-----_----_ 32 Vegetation.____________________________________________ 32 Domestic and industrial water supplies_____________________ 36 Health____-_--___________--_-_---_-----_-----_-_-_--_.__- 37 Power.______________________________________________ 38 Navigation._-_-----_-_____-_-_-_-_--__--_------_____--___ 39 Recreation and wild life--___--_---__--_-------------_--_-__ 41 Relief - ---- . 41 Drought of 1934__ 46 Causes_ _ ___________________________________________________ 46 Precipitation.____________________________________________ 47 Temperature._____________---_-___----_________-_________ 50 Wind_____________________________________________ -

C-261-1930-II EN.Pdf

I N LEAGUE OF NATIOKS. C.261/1930/11. Geneva, May 9th, 1930. HUNGARY. Iment by the F in an cial Committee of th ree members of the lining Commission of th e Agrarian Fund contemplated, under agreements signed in Peris on April 28th 1930 concerning obligations arising from the Treaty of Trianon. Re'oort by the Repre s ^ t a r^ve of Canada. / XV V / V The letter of the Presi&éryÇ^^The iMnancial Committee to the President of the Coun c i l /1^ich hèbs''^?è^nc i rcu.lat ed (Boc. C,?60/1930/II) is an enquiry'j/më/ther'"the* p'ouncil authorises the Financial Committee to ^ a m M Z ts v v |u s r s tio n and to report upon it to the Council beôoi©- any action is taken. It emerges from / Z lA I / O z ,xo y the Agreements signed xh Pêfï;^ on 23th April of this year that X / the appointments in qhg s t io ry's hou Id be made with the greatest despatch possible. The’Vunds to be administered by the Commission, now contemplated, begin to accumulate on July 1st next. Moreover it is obvious that the whole mechanism of the Paris Agreements, hich is dependent upon the constitution of this Agrarian Commission, hou Id be set in motion as so on as possible. In these circumstances the Council will doubtless wish o authorise the Financial Committee to proceed at once with its xamination of this question and to report to the Council upon t &t its present session. -

The London Gazette, 1 August, 1930

4806 THE LONDON GAZETTE, 1 AUGUST, 1930. The undermentioned officers are transferred Civil Service Commission, to the Unempld- List:— August 1, 1930. Lt.-Col. G. S. Renny, 15th July 1930. The Civil Service Commissioners hereby Lt.-Col. J. E. Carey, 26th July 1930. give notice th'at, on the application of the Lt. P. H. B. Edwards resigns his commn. Head of the Department, and with the 16th June 1930. approval of the Lords Commissioners of His Lt. Kin Maung, the resignation of whose Majesty's Treasury, the following class of em- coxnmn. was notified in the Gaz. of the 27th ployment under the Prison Commission, Home Sept. 1929, is permitted to retain the rank Office, has been added to the Schedule appended of Lt., 1st Aug. 1929. to the Order in Council of the 22nd July, 1920, namely: — INDIAN AEMY DEPARTMENTS. Unestablished employment as Assistant House Warden. Asst. Commy. & Lt. G. H. Holmes to be Depy. Commy. & Capt., 19th Mar. 1930. Condr. Bertram John Batt to be Asst. Commy. with rank of Lt., 27th May 1930. M.S.M. Albert Frederick Thomas Heaton, DISEASES OF ANIMALS ACTS, from R.A.S.C., to be Mechst. Officer with 1894 TO 1927. rank of Lt., 25th Feb. 1930, with seniority MINISTRY OF AGEICULTUEE AND FISHEEIES. next below Mechst. Officer & Lt. F. W. Notice is hereby given in pursuance of Whitaker. section 49 (3) of the Diseases of Animals Act, 1894, that the Minister of Agriculture and INDIAN MEDICAL SERVICE. Fisheries has made the following Order :— The promotions of the undermentioned officers to the rank of Maj. -

The German Currency Crisis of 1930

Why the French said “non”: Creditor-debtor politics and the German financial crises of 1930 and 1931 Simon Banholzer, University of Zurich Tobias Straumann, University of Zurich1 First draft July, 2015 Abstract Why did France delay the Hoover moratorium in June of 1931? In many accounts, this policy is explained by Germany’s reluctance to respond to the French gestures of reconciliation in early 1931 and by the announcement to form a customs union with Austria in March of 1931. The analysis of the German currency crisis in the fall of 1930 suggests otherwise. Already then, the French government did not cooperate in order to help the Brüning government to overcome the crisis. On the contrary, it delayed the negotiation process, thus acerbating the crisis. But unlike in 1931, France did not have the veto power to obstruct the rescue. 1 Corresponding author: Tobias Straumann, Department of Economics (Economic History), Zürichbergstrasse 14, CH–8032 Zürich, Switzerland, [email protected] 1 1. Introduction The German crisis of 1931 is one the crucial moments in the course of the global slump. It led to a global liquidity crisis, bringing down the British pound and a number of other currencies and causing a banking crisis in the United States and elsewhere. The economic turmoil also had negative political consequences. The legitimacy of the Weimar Republic further eroded, Chancellor Heinrich Brüning became even more unpopular. The British historian Arnold Toynbee quite rightly dubbed the year 1931 “annus terribilis”. As with any financial crisis, the fundamental cause was a conflict of interests and a climate of mistrust between the creditors and the debtor. -

Taylor University Bulletin (July 1930)

Taylor University Pillars at Taylor University Taylor University Bulletin Ringenberg Archives & Special Collections 7-1-1930 Taylor University Bulletin (July 1930) Taylor University Follow this and additional works at: https://pillars.taylor.edu/tu-bulletin Part of the Higher Education Commons Recommended Citation Taylor University, "Taylor University Bulletin (July 1930)" (1930). Taylor University Bulletin. 328. https://pillars.taylor.edu/tu-bulletin/328 This Book is brought to you for free and open access by the Ringenberg Archives & Special Collections at Pillars at Taylor University. It has been accepted for inclusion in Taylor University Bulletin by an authorized administrator of Pillars at Taylor University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. TAYLOR UNIVERSITY BULLETIN Entered as second class matter at Upland, Ind., April 8, 1900, undei Act of Congress, July 16, 1894 VOL. XXII., NUMBER III. JULY, 1930 ISSUED MONTHLY s at Taylor View of the "second home" of thousands of Taylor Made People. Photographed by the 1929-30 Gem Staff. The entrance to the Adminis tration Building is shown, with the Music Building in the background. Page Two TAYLOR UNIVERSITY BULLETIN THE TRANS NEPTUNE for three years, to Taylor's PLANET has been named Plu restful green campus. Not only to, which means "the dark and WHAT HAS the campus with all its beauti gloomy god." This harmonizes ful shrubs and flowers greeted with the plan of naming the oth me but also Taylor's faculty and er planets, after Greek and Ro HAPPENED student body. The years here man gods. The people at Lowell have meant rest of body and Observatory, Flagstaff, Arizona, growth of soul to me. -

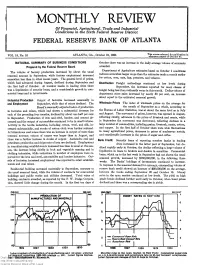

Economic Review

MONTHLY REVIEW Of Financial, Agricultural, Trade and Industrial Conditions in the Sixth Federal Reserve D istrict FEDERAL RESERVE BANK OF ATLANTA This review released for publication in VOL. 15, No. 10 ATLANTA, GA., October 31, 1930. afternoon papers of October 31. NATIONAL SUMMARY OF BUSINESS CONDITIONS October there was an increase in the daily average volume of contracts Prepared by the Federal Reserve Board awarded. The volume of factory production increased by about the usual Department of Agriculture estimates based on October 1 conditions seasonal amount in September, while factory employment increased indicate somewhat larger crops than the estimates made a month earlier somewhat less than in other recent years. The general level of prices, for cotton, com, oats, hay, potatoes, and tobacco. which had advanced during August, declined during September and Distribution Freight carloadings continued at low levels during the first half of October. At member banks in leading cities there September, the increases reported for most classes of was a liquidation of security loans, and a considerable growth in com freight being less than ordinarily occur in this month. Dollar volume of mercial loans and in investments. department store sales increased by nearly 30 per cent, an increase about equal to the estimated seasonal growth. Industrial Production Output of factories increased seasonally in and Employment September, while that of mines declined. The Wholesale Prices The index of wholesale prices on the average for Board’s seasonally adjusted index of production the month of September as a whole, according to in factories and mines, which had shown a substantial decrease for the Bureau of Labor Statistics, was at about the same level as in July each of the preceding four months, declined by about one half per cent and August. -

Nber Working Paper Series Austerity and the Rise Of

NBER WORKING PAPER SERIES AUSTERITY AND THE RISE OF THE NAZI PARTY Gregori Galofré-Vilà Christopher M. Meissner Martin McKee David Stuckler Working Paper 24106 http://www.nber.org/papers/w24106 NATIONAL BUREAU OF ECONOMIC RESEARCH 1050 Massachusetts Avenue Cambridge, MA 02138 December 2017 Earlier versions of this paper were presented at Oxford, UC Davis, UC Berkeley, Michigan, New York University, UCLA, University of Groningen, University of Bocconi, Australian National University, and UC Irvine. We thank seminar participants at those institutions. We would also like to thank Philipp Ager, Barbara Biasi, Víctor Durà-Vilà, Barry Eichengreen, Peter Lindert, Petra Moser, Burkhard Schipper, Veronica Toffolutti, Nico Voigtländer, Tamás Vonyó, Hans- Joachim Voth, and Noam Yuchtman, for a series of constructive suggestions and assistance. We acknowledge Maja Adena, Ruben Enikolopov, Hans-Joachim Voth and Nico Voigtländer for sharing data. The views expressed herein are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of the National Bureau of Economic Research. At least one co-author has disclosed a financial relationship of potential relevance for this research. Further information is available online at http://www.nber.org/papers/w24106.ack NBER working papers are circulated for discussion and comment purposes. They have not been peer-reviewed or been subject to the review by the NBER Board of Directors that accompanies official NBER publications. © 2017 by Gregori Galofré-Vilà, Christopher M. Meissner, Martin McKee, and David Stuckler. All rights reserved. Short sections of text, not to exceed two paragraphs, may be quoted without explicit permission provided that full credit, including © notice, is given to the source.