Questions Clients Are Asking About COVID-19

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

DDS WIRELESS INTERNATIONAL, INC. V. NUTMEG LEASING, INC. (AC 34278) Robinson, Bear and Peters, Js

****************************************************** The ``officially released'' date that appears near the beginning of each opinion is the date the opinion will be published in the Connecticut Law Journal or the date it was released as a slip opinion. The operative date for the beginning of all time periods for filing postopinion motions and petitions for certification is the ``officially released'' date appearing in the opinion. In no event will any such motions be accepted before the ``officially released'' date. All opinions are subject to modification and technical correction prior to official publication in the Connecti- cut Reports and Connecticut Appellate Reports. In the event of discrepancies between the electronic version of an opinion and the print version appearing in the Connecticut Law Journal and subsequently in the Con- necticut Reports or Connecticut Appellate Reports, the latest print version is to be considered authoritative. The syllabus and procedural history accompanying the opinion as it appears on the Commission on Official Legal Publications Electronic Bulletin Board Service and in the Connecticut Law Journal and bound volumes of official reports are copyrighted by the Secretary of the State, State of Connecticut, and may not be repro- duced and distributed without the express written per- mission of the Commission on Official Legal Publications, Judicial Branch, State of Connecticut. ****************************************************** DDS WIRELESS INTERNATIONAL, INC. v. NUTMEG LEASING, INC. (AC 34278) Robinson, Bear and Peters, Js. Argued March 21Ðofficially released September 10, 2013 (Appeal from Superior Court, judicial district of Ansonia-Milford, Hon. John W. Moran, judge trial referee.) Linda L. Morkan, with whom, on the brief, was Christopher J. -

Force Majeure and Common Law Defenses | a National Survey | Shook, Hardy & Bacon

2020 — Force Majeure SHOOK SHB.COM and Common Law Defenses A National Survey APRIL 2020 — Force Majeure and Common Law Defenses A National Survey Contractual force majeure provisions allocate risk of nonperformance due to events beyond the parties’ control. The occurrence of a force majeure event is akin to an affirmative defense to one’s obligations. This survey identifies issues to consider in light of controlling state law. Then we summarize the relevant law of the 50 states and the District of Columbia. 2020 — Shook Force Majeure Amy Cho Thomas J. Partner Dammrich, II 312.704.7744 Partner Task Force [email protected] 312.704.7721 [email protected] Bill Martucci Lynn Murray Dave Schoenfeld Tom Sullivan Norma Bennett Partner Partner Partner Partner Of Counsel 202.639.5640 312.704.7766 312.704.7723 215.575.3130 713.546.5649 [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] SHOOK SHB.COM Melissa Sonali Jeanne Janchar Kali Backer Erin Bolden Nott Davis Gunawardhana Of Counsel Associate Associate Of Counsel Of Counsel 816.559.2170 303.285.5303 312.704.7716 617.531.1673 202.639.5643 [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] John Constance Bria Davis Erika Dirk Emily Pedersen Lischen Reeves Associate Associate Associate Associate Associate 816.559.2017 816.559.0397 312.704.7768 816.559.2662 816.559.2056 [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] Katelyn Romeo Jon Studer Ever Tápia Matt Williams Associate Associate Vergara Associate 215.575.3114 312.704.7736 Associate 415.544.1932 [email protected] [email protected] 816.559.2946 [email protected] [email protected] ATLANTA | BOSTON | CHICAGO | DENVER | HOUSTON | KANSAS CITY | LONDON | LOS ANGELES MIAMI | ORANGE COUNTY | PHILADELPHIA | SAN FRANCISCO | SEATTLE | TAMPA | WASHINGTON, D.C. -

Force Majeure Tracker

Force majeure tracker April 2020 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY This guide has been prepared to address the substantial business and operational disruptions caused by the COVID-19 pandemic. Given the unexpected nature of the outbreak, parties to commercial contracts may seek to invoke force majeure or similar legal concepts to excuse delay or non-performance. This guide gives a high-level comparative analysis of force majeure in 28 jurisdictions, together with alternative remedies that may apply depending on the governing law of the relevant contracts. If you have any additional questions, please do not hesitate to contact our practitioners listed throughout the document. Asia Pacific EMEA The Americas 2 ASIA PACIFIC Jo Delaney Zhou Xi Roberta Chan Cynthia Tang Angela Ang Australia China Hong Kong Hong Kong Hong Kong +61 2 8922 5467 +86 10 5949 6019 +852 2846 2492 +852 2846 1708 +852 2846 1795 jo.delaney zhouxi roberta.chan cynthia.tang angela.ang @bakermckenzie.com @fenxunlaw.com @bakermckenzie.com @bakermckenzie.com @bakermckenzie.com Andi Kadir Timur Sukirno Yoshiaki Muto Kherk Ying Chew Donemark Calimon Indonesia Indonesia Japan Malaysia Philippines +62 21 2960 8511 +62 21 2960 8500 +81 3 6271 9451 +603 2298 7933 +63 2 8819 4920 andi.kadir timur.sukirno yoshiaki.muto kherkying.chew donemark.calimon @bakermckenzie.com @bakermckenzie.com @bakermckenzie.com @wongpartners.com @quisumbingtorres.com Daljit Kaur Nandakumar Ponniya Henry Chang Pisut Attakamol Singapore Singapore Taiwan Thailand +65 6434 2255 +65 6434 2663 +886 2 2715 7259 + 66 2636 2000 x 3131 daljit.kaur nandakumar.ponniya henry.chang pisut.attakamol @bakermckenzie.com @bakermckenzie.com @bakermckenzie.com @bakermckenzie.com Minh Tri Quach Fred Burke Vietnam Vietnam +84 24 3936 9605 +84 28 3520 2628 minhtri.quach frederick.burke @bmvn.com.vn @bakermckenzie.com 1 2 3 4 5 6 3 1 Is FM recognized in statute? If yes, what is impact of statutory rules on FM clauses in contracts? AUSTRALIA No statutory recognition. -

1 UNITED STATES BANKRUPTCY COURT DISTRICT of MASSACHUSETTS CENTRAL DIVISION in Re: CYPHERMINT, INC. Debtor ) ) ) ) ) ) ) Chapt

Case 10-04054 Doc 69 Filed 07/25/13 Entered 07/25/13 15:27:53 Desc Main Document Page 1 of 13 UNITED STATES BANKRUPTCY COURT DISTRICT OF MASSACHUSETTS CENTRAL DIVISION ) In re: ) Chapter 7 ) Case No. 08-42682-MSH CYPHERMINT, INC. ) ) Debtor ) ) ) JOSEPH H. BALDIGA, TRUSTEE ) ) Plaintiff ) Adversary Proceeding ) No. 10-04054 v. ) ) C.A. ACQUISITION CORP., C.A. ) ACQUISITION NEWCO, LLC, and ) PAYCASH MOBILE, LLC ) ) Defendants MEMORANDUM OF DECISION ON TRUSTEE’S MOTION FOR SUMMARY JUDGMENT The plaintiff in this adversary proceeding and the chapter 7 trustee in the main case, Joseph H. Baldiga, has moved for summary judgment on a complaint against defendants C.A. Acquisition Corp. (“C.A. Acquisition”), C.A. Acquisition Newco, LLC (“Newco”), and Paycash Mobile, LLC (“Paycash). The trustee’s claims against the defendants arise primarily from their alleged failure to comply with the terms of an agreement to purchase the assets of Cyphermint, Inc. (“Cyphermint”), the debtor in the main case. The defendants oppose the summary judgment motion. 1 Case 10-04054 Doc 69 Filed 07/25/13 Entered 07/25/13 15:27:53 Desc Main Document Page 2 of 13 Facts The relevant facts have been established by those allegations in the complaint admitted to by the defendants, the two affidavits and accompanying exhibits submitted by the trustee in support of his motion for summary judgment,1 and the facts in the trustee’s Concise Statement of Material Facts which have not been disputed by the defendants. On August 28, 2008, C.A. Acquisition offered to purchase the assets of the debtor. -

Contract Basics for Litigators: Illinois by Diane Cafferata and Allison Huebert, Quinn Emanuel Urquhart & Sullivan, LLP, with Practical Law Commercial Litigation

STATE Q&A Contract Basics for Litigators: Illinois by Diane Cafferata and Allison Huebert, Quinn Emanuel Urquhart & Sullivan, LLP, with Practical Law Commercial Litigation Status: Law stated as of 01 Jun 2020 | Jurisdiction: Illinois, United States This document is published by Practical Law and can be found at: us.practicallaw.tr.com/w-022-7463 Request a free trial and demonstration at: us.practicallaw.tr.com/about/freetrial A Q&A guide to state law on contract principles and breach of contract issues under Illinois common law. This guide addresses contract formation, types of contracts, general contract construction rules, how to alter and terminate contracts, and how courts interpret and enforce dispute resolution clauses. This guide also addresses the basics of a breach of contract action, including the elements of the claim, the statute of limitations, common defenses, and the types of remedies available to the non-breaching party. Contract Formation to enter into a bargain, made in a manner that justifies another party’s understanding that its assent to that 1. What are the elements of a valid contract bargain is invited and will conclude it” (First 38, LLC v. NM Project Co., 2015 IL App (1st) 142680-U, ¶ 51 (unpublished in your jurisdiction? order under Ill. S. Ct. R. 23) (citing Black’s Law Dictionary 1113 (8th ed.2004) and Restatement (Second) of In Illinois, the elements necessary for a valid contract are: Contracts § 24 (1981))). • An offer. • An acceptance. Acceptance • Consideration. Under Illinois law, an acceptance occurs if the party assented to the essential terms contained in the • Ascertainable Material terms. -

COVID-19 Legal Issues: Frequently Asked Questions

Litigation & Arbitration Group Client Alert COVID-19 Legal Issues: Frequently Asked Questions April 2, 2020 In managing the volatility and uncertainty caused by the global COVID-19 pandemic, many industries are grappling with complex legal and commercial challenges, from manufacturing shutdowns, interrupted supply chains and quarantines, to dislocated labor markets and restrictions on trade and movement, including the practical shutdown, or near shutdown, of substantial portions of the world economy. Moreover, governments have intervened to provide liquidity and emergency relief to credit markets and vulnerable industries and to preserve payrolls. Nonetheless, economic uncertainty has forced many companies, lenders and investors to seek guidance on their rights with respect to contractual obligations, especially in these key areas: • force majeure provisions • the doctrines of impossibility • material adverse effects and impracticability provisions • the frustration of purpose • ordinary course of business doctrine covenants • EBITDA maintenance covenants The analysis of any particular contract, transaction or dispute is always fact-specific and depends on, among other things, the specific contract language and conduct of the parties in each instance, as well as the relevant law applicable to that contract, transaction or dispute. Additionally, current market norms continue to evolve and legal rules cannot be interpreted in a vacuum. Regulatory and judicial interpretations of particular contract provisions, duties and applicable law may -

Contracts and Sales

Contracts and Sales MBE Testing Distribution MBE Question Breakdown ________ (I) Formation, (II) Consideration, (VII) Formation of Contracts: ________ Conditions, (IX) Impossibility, and (X) Consideration: ________ Discharge: Third-Party Beneficiary Contracts: ________ (III) Third-Party Beneficiaries, (IV) ________ Assignment and Delegation, (V) Statute Assignment and Delegation: ________ of Frauds, (IV) Parole Evidence, (VIII) Statute of Frauds ________ Remedies Parol Evidence and Interpretation ________ Conditions ________ Remedies ________ Impossibility, Impracticability, and ________ Frustration of Purpose Discharge of Contractual Duties ________ I. Formation of Contracts III. Third-Party Beneficiary Contracts A. Mutual Assent __ A. Intended Beneficiaries __ 1. Offer B. Incidental Beneficiaries __ 2. Acceptance C. Impairment or Extinguishment of Third- 3. Non-Conforming Acceptance Party Rights __ 4. Avoidance of Contract D. Enforcement by the Promisee __ B. Capacity to Contract __ IV. Assignment and Delegation C. Improper Contracts __ A. Assignment of Rights __ D. Implied-in-Fact Contracts and Quasi- Contracts __ B. Delegation of Duties __ E. Pre-Contract Detrimental Reliance __ V. Statue of Frauds F. Warranties __ A. Common Law __ II. Consideration B. Writing Requirement __ A. Bargained-for Exchange and Legal C. UCC __ Detriment __ VI. Parol Evidence and Interpretation B. Adequacy of Consideration __ A. Four Corners Rule __ C. Modern Substitutes for Bargain __ B. Collateral Contract Rule __ D. Modification of Contracts __ C. Evidence of Usage of Trade __ E. Compromise and Settlement of Claims D. Course of Dealing __ __ 1 VII. Conditions IX. Impossibility, Impracticability and A. Express Conditions __ Frustration of Purpose B. Constructive Conditions __ A. -

11/09/2020 Plaintiff's OTSC Directing Defendants Pay Rent Pendente Lite

FILED: NEW YORK COUNTY CLERK 11/09/2020 06:05 PM INDEX NO. 653839/2020 NYSCEF DOC. NO. 12 RECEIVED NYSCEF: 11/09/2020 SUPREME COURT OF THE STATE OF NEW YORK COUNTY OF NEW YORK ––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––– x EAST 16TH STREET OWNER LLC, : : Index No. 653839/2020 Plaintiff, : : - against - : : UNION 16 PARKING LLC and : TMO PARENT LLC, : : Defendants. : : ––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––– x MEMORANDUM OF LAW IN SUPPORT OF LANDLORD’S MOTION FOR AN ORDER DIRECTING DEFENDANTS TO PAY RENT PENDENTE LITE COZEN O’CONNOR Attorneys for Plaintiff 45 Broadway, 16th Floor New York, New York 10006 LEGAL\49080730\13 27979.0001.000/493058.000 1 of 22 FILED: NEW YORK COUNTY CLERK 11/09/2020 06:05 PM INDEX NO. 653839/2020 NYSCEF DOC. NO. 12 RECEIVED NYSCEF: 11/09/2020 TABLE OF CONTENTS Page PRELIMINARY STATEMENT .................................................................................................... 1 STATEMENT OF FACTS ............................................................................................................. 2 A. The Lease and the Parking Garage ............................................................................... 2 B. The Guaranties .............................................................................................................. 4 C. COVID-19 and Executive Orders ................................................................................. 5 D. Tenant Defaults on its Lease Obligations ..................................................................... 6 E. Procedural -

Misrepresentation: the Restatement’S Second Mistake

HOFFER.DOCX (DO NOT DELETE) 1/31/2014 2:04 PM MISREPRESENTATION: THE RESTATEMENT’S SECOND MISTAKE Stephanie R. Hoffer* The contract defenses of mistake and misrepresentation can be used to unravel deals as big as a corporate merger and as small as the sale of a used car. These two defenses, while conceptually distinct in theory, contain a significant amount of overlap in practice, causing courts to conflate the two legal standards. A misrepresentation of one party, when believed, results in a mistaken belief of the other, and both defenses address fundamental flaws in bargaining that throw the contracting parties’ consent into question. The coextensiveness of the defenses suggests that, absent an overriding normative justification, the legal test and remedy should be the same for each. Such a norma- tive justification exists only in the case of fraudulent misrepresentation which, unlike mistake or nonfraudulent misrepresentation, involves the intentional infliction of a dignitary harm. In such cases, punish- ment and deterrence are appropriate normative goals but neither are addressed by currently prevailing common law. Providing a single test for cases of misrepresentation and mistake with recourse to puni- tive damages in cases of fraud would harmonize the defenses with their normative underpinnings and eliminate inefficient redundancies in the common law. TABLE OF CONTENTS I. INTRODUCTION ................................................................................. 117 II. MISTAKE ........................................................................................... -

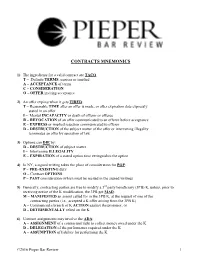

Contracts Mnemonics

CONTRACTS MNEMONICS 1) The ingredients for a valid contract are TACO: T – Definite TERMS, express or implied A – ACCEPTANCE of terms C – CONSIDERATION O – OFFER inviting acceptance 2) An offer expires when it gets TIRED: T – Reasonable TIME after an offer is made, or after expiration date expressly stated in an offer I – Mental INCAPACITY or death of offeror or offeree R – REVOCATION of an offer communicated to an offeree before acceptance E – EXPRESS or implied rejection communicated to offeror D – DESTRUCTION of the subject matter of the offer or intervening illegality terminates an offer by operation of law 3) Options can DIE by: D – DESTRUCTION of subject matter I – Intervening ILLEGALITY E – EXPIRATION of a stated option time extinguishes the option 4) In NY, a signed writing takes the place of consideration for POP: P – PRE–EXISTING duty O – Contract OPTIONS P – PAST consideration (which must be recited in the signed writing) 5) Generally, contracting parties are free to modify a 3rd party beneficiary (3PB) K, unless, prior to receiving notice of the K modification, the 3PB got MAD: M – MANIFESTED an assent called for in the 3PB K, at the request of one of the contracting parties (i.e., accepted a K offer arising from the 3PB K) A – Commenced a breach of K ACTION against the promisor, or D – DETRIMENTALLY relied on the K 6) Contract assignments may involve the ADA: A – ASSIGNMENT of a contractual right to collect money owed under the K D – DELEGATION of the performance required under the K A – ASSUMPTION of liability for performing -

When a Commercial Contract Doesn't Have a Force Majeure Clause

April 24, 2020 WHEN A COMMERCIAL CONTRACT DOESN’T HAVE A FORCE MAJEURE CLAUSE: COMMON LAW DEFENSES TO CONTRACT ENFORCEMENT To Our Clients and Friends: The rapid spread of the COVID-19 pandemic, and stringent government orders regulating the movement and gathering of people issued in response, continues to raise concerns about parties’ abilities to comply with contractual terms across a variety of industries. As discussed previously here, force majeure clauses may address parties’ obligations under such circumstances. Even without force majeure clauses, depending on the circumstances parties may seek to invalidate contracts or delay performance under the common law based on COVID-19. To assist in considering such issues, we have prepared the following overview. As the analysis of the applicability of any of the doctrines below is fact-specific and fact- intensive, this overview is intended only as a starting point. We encourage you to reach out to your Gibson Dunn contact to discuss specific questions or issues that may arise. Impossibility of Performance The doctrine of impossibility is available where performance of a contract is rendered objectively impossible.[1] In assessing whether impossibility of performance applies to your situation and your contract, it is useful first to determine whether the jurisdiction applicable to your contract or dispute has codified the doctrine. As in California, the statutory language might provide guidance to or place limitations on its applicability.[2] A party seeking to invoke the impossibility doctrine under common law must show that the impossibility was produced by an unanticipated event and the event could not have been foreseen or guarded against in the contract.[3] Courts have held that impossibility of performance during times of emergency or disaster has generally excused performance on the basis of governing law, governmental regulations, or the disruption of transportation or communication networks. -

Contractual Impossibility and Frustration of Purpose in the Face of the COVID- 19 Epidemic by Lisa Bentley

Contractual Impossibility and Frustration of Purpose in the Face of the COVID- 19 Epidemic By Lisa Bentley The outbreak of the global epidemic now known as COVID-19, which has come to be all too familiar to us in the past few weeks, is a story that has only just begun. As many of us watch this current health and economic calamity unfold, it is simply not clear at this point what the myriad of long-term effects of the virus will be on our world. As commercial litigators, however, one thing that we can realistically expect is that the performance of thousands of commercial contracts will be jeopardized. From cross-border contracts for the purchase and sale of goods, to lease agreements for retail space, to contracts for international mergers and acquisitions, to agreements for the use of event space, businesses are likely to be faced with the fact that performance if their commercial contracts is no longer possible, is extremely difficult, or just no longer makes any sense. Impossibility, Impracticality and Frustration of Purpose. When faced with such situations, businesses might look to the doctrines of contractual impossibility, or impracticality, or the related doctrine of frustration of purpose. While limited in their applicability, these doctrines are defenses that a contracting party may invoke to their performance obligations under a contract. The defense of impossibility, or impracticality, may be available when there is an unanticipated event that could not have been foreseen or guarded against in a contract.[1] Frustration of purpose