Sarah Whetstone, 2016

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

R5 Aktuella Med Ny Ep - Kommer Till Stockholm Och Malmö

R5 2017-06-20 10:41 CEST R5 AKTUELLA MED NY EP - KOMMER TILL STOCKHOLM OCH MALMÖ Högaktuella med nya EP:n "New Addictions" beger sig Kalifornia-bandet R5 ut på turné! Syskonen Ross, Riker, Rocky och Rydel Lynch - samt vännen och trummisen Ellington Ratliff - är en världssensation! Med hits som "Smile", "Pass Me By" och "I Feel The Love" är R5 en pop rock-ångvält i musikvärlden. Nu kommer de hit! Lördag 30 september på Fryshuset i Stockholm och söndag 1 oktober på KB i Malmö! Biljetter släpps 26 juni klockan 09.00 via LiveNation.se Det är svårt att inte ryckas med i de hits som R5 skapat genom åren. Låtarna på nya EP:n "New Addictions" är inget undantag. Skivan är den första som bandet har gjort till största del på helt egen hand - där Rocky Lynch (annars på gitarr i bandet) har producerat hela skivan. Ross Lynch beskriver deras arbete bäst: "Every new thing we make will be different from what we've done in the past, but on this EP we really got into a whole new groove with our writing. Instead of trying to make this kind of tune or that kind of tune, we're just completely giving in and letting the music decide for itself." Vi rekommenderar starkt att du kollar in "New Addictions" på Spotify och gör dig redo för biljettsläppet den 26 juni. Konserterna med R5 lär bli det allra bästa sättet att kicka igång hösten på! Ses på Fryshuset och KB! Datum 30/9 - Fryshuset, Stockholm 1/10 - KB, Malmö Biljetter Biljetterna släpps den 26 juni kl 09.00. -

The New Music Project from Ross and Rocky Lynch

The New Music Project from Ross and Rocky Lynch Makes Billboard Debut at #39 on Alternative Songs Chart "Preacher Man" Remixes Out Now THE DRIVER ERA, the much-buzzed about music project from brothers Ross and Rocky Lynch, have made their official Billboard chart debut at #39 on the Alternative Songs chart with their single "Preacher Man". At over 3 million audio streams and almost 2 million views on the official video, the hit has made waves in the music space, earning praise from Paper Magazine, Billboard, Ones to Watch and more. "If 'Preacher Man' were a cocktail, it would be equal parts Elton John and Freddie Mercury with just a dash of Timberlake - and a bit of a burn on the aftertaste." - LADYGUNN Download/stream "Preacher Man" here. THE DRIVER ERA's Rocky Lynch partnered with GRAMMY Nominated producer Lipless to create a remix package, out everywhere today. Click here to stream "Preacher Man - Lipless Remix" and here for "Preacher Man - Rocky Remix". "Preacher Man" is featured on Apple Music's Songs of the Summer, a playlist that highlights the very best of Pop, dance, hip hop, and R&B hits to soundtrack the perfect summer. Other artists on the playlist include Ariana Grande, Shawn Mendes, Post Malone, lovelytheband and more. Click here to stream. About The Driver Era: Like the band name, the music of The Driver Era captures a certain classic feeling while looking toward tomorrow. With the two brothers, Ross and Rocky Lynch, writing, performing, and producing most of the tracks, their stylistically unpredictable pop also conjures up every romantic association with heading out on the open road: limitless possibility, the thrill of escape, a refusal to stay in one place for any real length of time. -

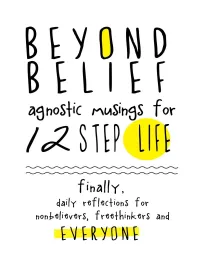

Beyond Belief Is an Inclusive Conversation About Recovery and Addiction

© 2013 Rebellion Dogs Publishing-second printing 2014 All rights reserved. No portion of this book may be reproduced in any form or by any electronic or mechanical means, including information storage and retrieval systems, without the written consent of the publisher. Not sure? Please contact the publisher for permission. Rebellion Dogs Publishing 23 Cannon Road, Unit # 5 Toronto, ON Canada M8Y 1R8 [email protected] http://rebelliondogspublishing.com ISBN # 978-0-9881157-1-2 1. addiction/recovery, 2. self-help, 3. freethinking/philosophy The brief excerpts from Pass it On, Twelve Steps and Twelve Traditions, Living Sober, Alcoholics Anonymous Comes of Age, The Big Book and “Box 4-5-9” are reprinted with permission from Alcoholics Anonymous World Services, Inc. (“AAWS”) Permission to reprint these excerpts does not mean that AAWS has reviewed or approved the contents of this publication, or that AAWS necessarily agrees with the views expressed herein. A.A. is a program of recovery from alcoholism only—use of these excerpts in connection with programs and activities which are patterned after A.A., but which address other problems, or in any other non- A.A. context, does not imply otherwise. Additionally, while A.A. is a spiritual program, A.A. is not a religious program. Thus, A.A. is not affiliated or allied with any sect, denomination, or specific religious belief. See our end notes and bibliography for more referenced material contained in these pages. ABOUT THIS BOOK: It doesn’t matter how much we earn, who we know, our education or what we believe. We are all susceptible to process or substance addiction. -

R5 Loud Ep Album Download

R5 Loud Ep Album Download 1 / 4 R5 Loud Ep Album Download 2 / 4 3 / 4 Loud Ep. +. Louder. +. Sometime Last Night. Total price: $25.98. Add all three to Cart Add all three to List. Some of these items ship sooner than the others.. 13 Feb 2015 - 36 sec - Uploaded by Eros Garciafor the release of the new single let's not be alone tonight i'm uploading all the previous songs .... Description Pre-order the new album LOUDER and get an instant download of the new single "Pass Me By" ... "Loud " is the title song off of R5's EP "LOUD ".. If you are a R5 Family member, well this page is right for you! This page is dedicated to the ... Preview and download Loud EP on iTunes. See ratings and read .... Louder (Deluxe) - R5 [Itunes Plus AAC M4A] (2013) ... 12- Loud (Acoustic) ... We´re trying to put all the songs/Albums/EP´s/Soundtracks as soon as we can.. Loud is the lead single from American pop rock band R5's second EP of the same ... tracks and was later included on the band's debut full-length album, Louder .. 19 Feb 2013 ... 'Loud EP' by R5 - an overview of this albums performance on the American iTunes chart. ... Download "Loud EP" from the iTunes store.. 2 Mar 2013 ... R5 – Loud – EP Zip Quality: iTunes Plus AAC M4A Download Free Zippyshare ... CLICK THIS LINK TO DOWNLOAD THE FULL ALBUM. Loud is the debut EP by American pop rock band R5. It was released on February 19, 2013 ... United States, February 19, 2013, digital download · Hollywood Records .. -

Ross and Rocky Lynch Announce New Music Project Hear Their

Ross and Rocky Lynch Announce New Music Project Hear Their Debut Single “Preacher Man” Now Brothers Ross and Rocky Lynch have launched a brand new music project - THE DRIVER ERA - with their debut single "Preacher Man"out everywhere today via TOO Records. Co-written by Julian Bunetta and team, Family Affair (songwriters behind hits for One Direction, Charlie Puth and more), the genre blending single emanates influences of pop and rock & roll, and a maturity the brothers felt was best suited for a new musical outlet. "It was a combination of ideas, but also just the idea that we needed to change something," Ross explained in a recent interview with Billboard. "Our goal, as any artist should be, is to try and push the boundaries of not only ourselves, but of the music, and also excite people. As an artist, you want to entertain people. The reason we started The Driver Era is because our creative endeavors sort of demanded it." Download/stream "Preacher Man" everywhere now: http://smarturl.it/PreacherMan. About The Driver Era: Like the band name, the music of The Driver Era captures a certain classic feeling while looking toward tomorrow. With the two brothers, Ross and Rocky Lynch, writing, performing, and producing most of the tracks, their stylistically unpredictable pop also conjures up every romantic association with heading out on the open road: limitless possibility, the thrill of escape, a refusal to stay in one place for any real length of time. On their debut single "Preacher Man," The Driver Era channel their restless creativity into what's arguably one of pop music's most epic themes: the existential crisis. -

SEPTEMBER 2019 • FREE Published by the Beacon Newspapers, Inc

Published by The Beacon Newspapers, Inc. SEPTEMBER 2019 • FREE 2 www.FiftyPlusRichmond.com SEPTEMBER 2019 — FIFTYPLUS That could be true. But in most cases, I scan the QR code (the box on the right), believe, businesses and political candi- or using a tablet or a computer enabled Your opinion, please dates really want to know what you think. with a camera (for Skype, for example) go There’s only one thing that no one can order a product from Amazon and are A business can’t survive if it isn’t meeting to bit.ly/proudest, and after answering one give you or take away from you: your opin- asked to rate it or submit a comment. the needs of its customers. A candidate or question, you can tell us via video what you ion. Especially during campaign politician who wants to represent voters are most proud of in your life. You’ll have What you think in your seasons, we walk down the well needs to know what they think. up to 30 seconds for your video. mind and feel in your heart is street and are asked to sign a So try not to feel too jaded when asked Or if you prefer, you can share with us uniquely and always yours. petition or “answer a few for your opinion. Only you know what you what you think about Fifty Plus, this col- Your opinion might change questions” to help a pollster. think — until you are asked to express it. umn, or any other topic of the day that in- from time to time, even from We take a survey somewhere And that is when your opinion starts to terests you. -

The Music Project from Ross and Rocky Lynch

The Music Project from Ross and Rocky Lynch Debuts New Single "LOW" "LOW" Featured on Ross's Teen Party Playlist Takeover via Spotify - Stream HERE Ross Starring in Netflix's The Chilling Adventures of Sabrina - Out TODAY THE DRIVER ERA, the much-buzzed about music project from brothers Ross and Rocky Lynch, have released their new genre-defying single "Low," out everywhere today. Written and produced by Rocky Lynch himself, the track premiered earlier this week on Consequence of Sound. "Groovy strums, smoky synths, and an urgent beat merge with atmospheric vocal effects that give Rocky's sultry delivery a depth that suits the song's tenderness." - Ben Kaye, Consequence of Sound. Stream "LOW" everywhere HERE. "Low" comes after the band's laid-back summer jam "Afterglow" and their pop-rock debut "Preacher Man." "Preacher Man" debuted at #15 and #21 on Billboard's Alternative & Rock Sales Chart, and currently sits at over 11 Million combined audio streams. Since it's release, the band has graced the cover of both Ladygunn and Grumpy Magazine, and have earned praise from V Magazine, Cosmopolitan, Live Nation's Ones to Watch, Elle Magazine and more. "Combining Alt-Rock with EDM and hints of trap produced beats, their multifaceted take on pop music is sending them up the charts." - Flaunt "Their new music feels fresh, alive and bursting with flavor." - Paper The Driver Era played a few festival dates over the summer, including 107.7 The End Summer Camp, and most recently Jay-Z's Made in America Festival. The band will play Florida Man Music Festival in Orlando on 11/30 with Weezer, Young The Giant, Bishop Briggs and more, and will share the stage with the likes of Panic! At The Disco, Sublime and more at Riptide Music Festival on 12/1 in Fort Lauderdale, FL. -

Online Behavioral Boundaries: an Investigation of How Engaged Couples Negotiate Agreements Regarding What Is Considered Online Infidelity

Online Behavioral Boundaries: An Investigation of How Engaged Couples Negotiate Agreements Regarding What is Considered Online Infidelity Tenille Anise Richardson-Quamina Dissertation submitted to the faculty of the Virginia Polytechnic Institute and State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy In Human Development Fred P. Piercy, Chair Katherine R. Allen Mark J. Benson Christine E. Kaestle April 24, 2015 Blacksburg, VA Keywords: Online Infidelity, Relationship Agreements, Engaged Couples Online Behavioral Boundaries: An Investigation of How Engaged Couples Negotiate Agreements Regarding What is Considered Online Infidelity Tenille Anise Richardson-Quamina ABSTRACT Previous research has examined the various types of online infidelity, gender differences in online sexual behaviors, and relationship consequences of online affairs. Despite this attention, there remains a research gap regarding ways to prevent online infidelity. When couples seek therapy to address this issue, therapists report a lack of specific preparedness. This qualitative research project focused on methods for assisting couples by studying how they develop an agreement regarding appropriate and inappropriate online behaviors. Grounded theory was used to analyze the data from dyadic interviews with 12 engaged heterosexual couples. The interviews generated five common steps in the process of developing an agreement: (a) discuss the various online activities the couple participates in online; (b) define online infidelity; (c) discuss which activities are appropriate and which are not appropriate; (d) develop rules; and (e) state what occurs when an agreement is violated. Three couples had developed an agreement prior to the study and two couples developed an agreement through the process of the interview.