Barnsley Character Zone Descriptions

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Trail Trips - Old Moor to Old Royston

Trail Trips - Old Moor to Old Royston RSPB Old Moor to Old Royston (return) – 20 miles (32Km) Suitable for walkers, cyclists and equestrians in parts - this section is also suitable for families who can shorten the route by turning back at either the start of the Dove Valley Trail (Aldham Junction 2.5 miles) or at Stairfoot (McDonalds 3.8 miles). TPT Map 2 Central: Derbyshire - Yorkshire RSPB Old Moor Visitor Centre Turn right once through the gate Be careful when crossing the road Starting out in the heart of Dearne Valley, at the nature reserve of RSPB Old Moor, leave the car park to the rear, cross over the bridge, through the gate (please be aware that RSPB Old Moor car park opening times vary depending on the time of year and the gates do get locked at night) and turn right . Follow the trail under the bridge, where you will notice some murals. As you come out the other side, go over the wooden bridge and continue straight on until you come to the road. Take care crossing, as the road can become busy. Once over the road, the trail is easy to follow. Shortly after crossing the road you will come across the start of the Timberland Trail if you wish you can head south on the Trans Pennine Trail to- wards Elsecar and Sheffield). Continue north along the Trail, passed Wombwell where you will come to the start of the Dove Valley Trail (follow this and it will take you to Worsbrough, Silkstone and to the historical market town of Penistone and if you keep going you will eventually end up in Southport on the west coast!!). -

Valid From: 12 April 2021 Bus Service(S) What's Changed Areas

Bus service(s) X10 Valid from: 12 April 2021 Areas served Places on the route Barnsley Barnsley Interchange New Lodge Mapplewell Darton Kexborough Leeds What’s changed Timetable changes. Operator(s) How can I get more information? TravelSouthYorkshire @TSYalerts 01709 51 51 51 Bus route map for service X10 Roundhay Aberford25/10/2018 Headingley Leeds, Crown Point Road Farsley Leeds City Bus Station, Dyer Street X10 Leeds, Black Bull Street Garforth Pudsey New Farnley Beeston Swillington Kippax Churwell Rothwell Woodlesford Gildersome Middleton Oulton Morley Carlton Mickletown Methley West Ardsley Batley Whitwood Altofts Stanley Normanton Dewsbury Ackton Ravensthorpe Warmfield Ossett Wakefield Thornhill Edge Sharlston Horbury West Hardwick Crofton Walton Netherton Wintersett Fitzwilliam Flockton Midgley Emley Moor Notton Emley Haigh, M1 Roundabout South Hiendley Haigh, Huddersfield Road/Sheep Lane Head Darton, Church Street/Church Close Mapplewell, Blacker Road/Church Street Brierley ! Kexborough, Ballfield Lane/Priestley Avenue Carlton Darton, Church Street/Health Centre New Lodge, Wakefield Road/Laithes Lane ! Mapplewell, Towngate/Four Lane Ends Denby Dale Cudworth New Lodge, Wakefield Road/Langsett Road Barnsley, Interchange ! X10 Dodworth Penistone ! Contains Ordnance Survey data © Crown copyright and database right 2018 and copyright Crown data © Survey Ordnance Contains 2018 = Terminus point = Public transport = Shopping area = Bus route & stops = Rail line & station = Tram route & stop Limited stop Service X10 is non-stop between Barnsley, -

Carlton Ind Estate Barnsley 2Pp Hi Res.Q:Layout 1

TO LET Warehouse / Industrial Unit 120,343 sq ft (11,180.1 sq m) Unit 19 | Carlton Industrial Estate | Barnsley | S71 3PQ Unit 19 | Carlton Industrial Estate | Barnsley | S71 3PQ y 1 43 M621 Ryhill 27 37 Birstall 30 Castleford 41 32 31 36 Woolley Notton 33 34 M62 40 Pontefract Dewsbury Wakefield South M18 Hiendley 39 6 Thorne 38 Hemsworth 38 5 1 M1 38 M180 2 Royston Woolley 37 Barnsley 37 4 Grange Shafton Brierley DONCASTER A628 36 36 A637 M1 3 Stocksbridge Robin Hood 35 M18 Darton Carlton E A1(M) N A628 G Rotherham Industrial I N 34 E L 33 A637 N Indicative boundary. 32 34 Estate Cudworth Grimethorpe SHEFFIELD 31 Barugh Green DESCRIPTION BUSINESS RATES Higham A 5 bay steel portal frame distribution unit, We understand from the VOA that the property A635 with a typical eaves height of approximately has the following assessment for Business Rates: M1 ACT RD 6.6m. Loading access into the unit is by way Local Authority Reference - 51010309960714 FR A628 BARNSLEY E NT of 2 ground level doors to the rear yard, and Description - Warehouse and Premises 37 PO a further 2 to the front yard. The unit benefits DONCASTER RD T Rateable Value 2017 - £161,000 DONCAS ER R from lighting. A6133 D Interested parties should satisfy themselves in A635 There is a small office and welfare pod on the this regard. front elevation. PLANNING ACCOMMODATION The unit’s most recent use has been storage and distribution, and we are not aware of any We have measured the property to have the hours of use or other restrictions. -

Committee Report

Report Precis Report of the Assistant Director Planning and Transportation to the Planning Regulatory Board Date: 15/12/2009 Doc No Subject Applications under Town and Country Planning Legislation. Purpose of Report This report presents for decision planning, listed building, advertisement, Council development applications and also proposals for works to or felling of trees covered by a Preservation Order and miscellaneous items. Information The proposals presented for decision are set out within the index to the front of the attached report. Applications included under Section A are recommended for approval and conditions are summarised at the end of each application. Applications listed under Section B are recommended for refusal and the reason(s) for refusal are set out at the end of each application. Other sections of the report may include consultations by neighbouring planning authorities and miscellaneous items. Access for the Disabled Implications Where there are any such implications they will be referred to within the individual report. Financial Implications None Crime and Disorder Implications Where there are any such implications they will be referred to within the individual reports. Human Rights Act The Council has considered the general implications of the Human Rights Act in this agenda report. 1 Representations Where representations are received in respect of an application, a summary of those representations is provided in the application report which reflects the key points that have been expressed regarding the proposal. Members are reminded that they have access to all documentation relating to the application, including the full text of any representations and any correspondence which has occurred between the Council and the applicant or any agent of the applicant. -

To Registers of General Admission South Yorkshire Lunatic Asylum (Later Middlewood Hospital), 1872 - 1910 : Surnames L-R

Index to Registers of General Admission South Yorkshire Lunatic Asylum (Later Middlewood Hospital), 1872 - 1910 : Surnames L-R To order a copy of an entry (which will include more information than is in this index) please complete an order form (www.sheffield.gov.uk/libraries/archives‐and‐local‐studies/copying‐ services) and send with a sterling cheque for £8.00. Please quote the name of the patient, their number and the reference number. Surname First names Date of admission Age Occupation Abode Cause of insanity Date of discharge, death, etc No. Ref No. Laceby John 01 July 1879 39 None Killingholme Weak intellect 08 February 1882 1257 NHS3/5/1/3 Lacey James 23 July 1901 26 Labourer Handsworth Epilepsy 07 November 1918 5840 NHS3/5/1/14 Lack Frances Emily 06 May 1910 24 Sheffield 30 September 1910 8714 NHS3/5/1/21 Ladlow James 14 February 1894 25 Pit Laborer Barnsley Not known 10 December 1913 4203 NHS3/5/1/10 Laidler Emily 31 December 1879 36 Housewife Sheffield Religion 30 June 1887 1489 NHS3/5/1/3 Laines Sarah 01 July 1879 42 Servant Willingham Not known 07 February 1880 1375 NHS3/5/1/3 Laister Ethel Beatrice 30 September 1910 21 Sheffield 05 July 1911 8827 NHS3/5/1/21 Laister William 18 September 1899 40 Horsekeeper Sheffield Influenza 21 December 1899 5375 NHS3/5/1/13 Laister William 28 March 1905 43 Horse keeper Sheffield Not known 14 June 1905 6732 NHS3/5/1/17 Laister William 28 April 1906 44 Carter Sheffield Not known 03 November 1906 6968 NHS3/5/1/18 Laitner Sarah 04 April 1898 29 Furniture travellers wife Worksop Death of two -

Windsor Avenue Kexbrough Barnsley S75 5Ln

WINDSOR AVENUE KEXBROUGH BARNSLEY S75 5LN . THIS WELL PRESENTED THREE BEDROOM SEMI DETACHED PROPERTY OFFERS WELL PROPORTIONED ACCOMMODATION IN THIS POPULAR AREA OF KEXBROUGH WITHIN EXCELLENT PROXIMITY TO THE M1 MOTORWAY, MAJOR TRANSPORT LINKS AND WITHIN EASY REACH OF BARNSLEY AND WAKEFIELD. The accommodation briefly comprises dining kitchen, utility, lounge and conservatory. To the first floor are three good sized bedrooms and modern bathroom. Outside are gardens to the front and rear with driveway providing off-street parking for numerous vehicles. Viewing is essential to be fully appreciated. Offers around £135,000 16 Regent Street, Barnsley, South Yorkshire, S70 2HG Tel: 01226 731730 www.simonblyth.co.uk . UTILITY . Access gained via composite door with glazed panels into the utility. There are a range of wall and base units ina white high gloss with contrasting laminate worktop, plumbing for a washing machine, tumble dryer and space for an America style fridge freeze. There is laminate flooring, radiator, ceiling light and uPVC door giving access to the rear garden. DINING KITCHEN . This fabulous open plan space has a range of wall and base units in wood shaker style with contrasting laminate worktops and tiled splashbacks, space for cooker and stainless steel sink with chrome mixer tap over. There is ceiling light, uPVC double glazed window to the rear overlooking the garden and under cupboard lighting. The dining area has ample room for a table and chairs with ceiling light, central heating radiator and uPVC double glazed window to the side elevation. Staircase rises to the first floor with useful storage cupboard underneath. -

Local Environment Agency Plan

EA-NORTH EAST LEAPs local environment agency plan SOUTH YORKSHIRE AND NORTH EAST DERBYSHIRE CONSULTATION REPORT AUGUST 1997 BEVERLEY LEEDS HULL V WAKEFIELD ■ E n v ir o n m e n t A g e n c y Information Services Unit Please return or renew this item by the due date Due Date E n v ir o n m e n t A g e n c y YOUR VIEW S Welcome to the Consultation Report for the South Yorkshire and North East Derbyshire area which is the Agency's view of the state of the environment and the issues that we believe need to be addressed during the next five years. We should like to hear your views: • Have we identified all the major issues? • Have we identified realistic proposals for action? • Do you have any comments to make regarding the plan in general? During the consultation period for this report the Agency would be pleased to receive any comments in writing to: The Environment Planner South Yorkshire and North East Derbyshire LEAP The Environment Agency Olympia House Gelderd Road Leeds LSI 2 6DD All comments must be received by 31st December 1997. All comments received on the Consultation Report will be considered in preparing the next phase, the Action Plan. This Action Plan will focus on updating Section 4 of this Consultation Report by turning the proposals into actions with timescales and costs where appropriate. All written responses will be considered to be in the public domain unless consultees explicitly request otherwise. Note: Whilst every effort has been made to ensure the accuracy of information in this report it may contain some errors or omissions which we shall be pleased to note. -

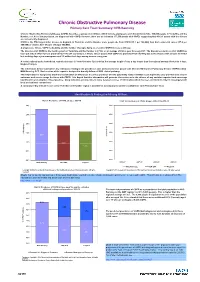

Draft COPD Profiles V10.Xlsm

Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease Primary Care Trust Summary: NHS Barnsley Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease (COPD) describes a group of conditions which include emphysema and chronic bronchitis. 100,000 people in Yorkshire and the Humber, or 1.9% of the population, are diagnosed with COPD. However, there are an estimated 177,000 people with COPD, suggesting that 43% of people with the disease are not currently diagnosed. COPD is the fifth largest killer disease in England. In Yorkshire and the Humber more people die from COPD (31.1 per 100,000) than from colorectal cancer (17.4 per 100,000) or chronic liver disease (10.4 per 100,000). A progressive illness, COPD is disabling and the number of people dying as a result of COPD increases with age. The direct cost of COPD to the health system in Yorkshire and the Humber is £77m: or an average of £5m a year for every PCT. The broader economic cost of COPD has been put at £3.8 billion for lost productivity in the UK economy as a whole. 25% of people with COPD are prevented from working due to the disease with at least 20 million lost working days a year among men and 3.5 million lost days among women every year. A recent national audit showed that readmission rates in Yorkshire were 32% and that the average length of stay a day longer than the national average (Yorkshire 6 days, England 5 days). The information below summarises key indicators relating to the prevalence, care and outcomes for people with Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease (COPD) within NHS Barnsley PCT. -

Proposed Access Work Darton Health Centre Darton, Barnsley S75 5HQ

Design and Access Statement 14256 – Darton Health Centre, Darton, Barnsley Proposed Access Work Darton Health Centre Darton, Barnsley S75 5HQ for NHS Property Services Design and Access Statement Rance Booth Smith Architects 11 Victoria Road Saltaire Shipley West Yorkshire BD18 3LA 01274 587327 [email protected] www.rbarchitects.co.uk Design and Access Statement 14256 – Darton Health Centre, Darton, Barnsley 1.0 Introduction This report supports a full planning application, submitted on behalf of NHS Property Services, for the proposed modifications to the existing entrance of Darton Health Centre to improve access for disabled or partially disabled visitors to the Health Centre. This statement should be read together with all additional documents submitted for this application. 2.0 Site Description and Setting The site is located on the corner of Church Road and Church Close, Darton, Barnsley S75 7HQ in South Yorkshire. Access into and out of the building is currently via a sloping path that has a gradient of approximately 1:14. There is no intermediate landing and only one handrail which is at approximately 1100mm from the gradient pitch line which is outside the limits of the required 900mm height. There is also no upstand to either side of the gradient. This is the only access to and from the building for visitors as there is no stepped access. The main visitors’ car park is across the road on Church Close. Dropped kerbs are already in place. There is also another car park to the rear of the building. Visitor access from this car park is via the existing footpath and up to the area where the entrance gradient begins at the corner of Church Road and Church Close. -

International Passenger Survey, 2008

UK Data Archive Study Number 5993 - International Passenger Survey, 2008 Airline code Airline name Code 2L 2L Helvetic Airways 26099 2M 2M Moldavian Airlines (Dump 31999 2R 2R Star Airlines (Dump) 07099 2T 2T Canada 3000 Airln (Dump) 80099 3D 3D Denim Air (Dump) 11099 3M 3M Gulf Stream Interntnal (Dump) 81099 3W 3W Euro Manx 01699 4L 4L Air Astana 31599 4P 4P Polonia 30699 4R 4R Hamburg International 08099 4U 4U German Wings 08011 5A 5A Air Atlanta 01099 5D 5D Vbird 11099 5E 5E Base Airlines (Dump) 11099 5G 5G Skyservice Airlines 80099 5P 5P SkyEurope Airlines Hungary 30599 5Q 5Q EuroCeltic Airways 01099 5R 5R Karthago Airlines 35499 5W 5W Astraeus 01062 6B 6B Britannia Airways 20099 6H 6H Israir (Airlines and Tourism ltd) 57099 6N 6N Trans Travel Airlines (Dump) 11099 6Q 6Q Slovak Airlines 30499 6U 6U Air Ukraine 32201 7B 7B Kras Air (Dump) 30999 7G 7G MK Airlines (Dump) 01099 7L 7L Sun d'Or International 57099 7W 7W Air Sask 80099 7Y 7Y EAE European Air Express 08099 8A 8A Atlas Blue 35299 8F 8F Fischer Air 30399 8L 8L Newair (Dump) 12099 8Q 8Q Onur Air (Dump) 16099 8U 8U Afriqiyah Airways 35199 9C 9C Gill Aviation (Dump) 01099 9G 9G Galaxy Airways (Dump) 22099 9L 9L Colgan Air (Dump) 81099 9P 9P Pelangi Air (Dump) 60599 9R 9R Phuket Airlines 66499 9S 9S Blue Panorama Airlines 10099 9U 9U Air Moldova (Dump) 31999 9W 9W Jet Airways (Dump) 61099 9Y 9Y Air Kazakstan (Dump) 31599 A3 A3 Aegean Airlines 22099 A7 A7 Air Plus Comet 25099 AA AA American Airlines 81028 AAA1 AAA Ansett Air Australia (Dump) 50099 AAA2 AAA Ansett New Zealand (Dump) -

Notes from the Area's Ward Alliances PDF 960 KB

BARNSLEY METROPOLITAN BOROUGH COUNCIL North Area Council Meeting: Monday 19th July 2021 Report of North Area Council Agenda Item: 9 Manager North Area Ward Alliance – Operational Updates 1. Purpose of Report 1.1 This report apprises the North Area Council of the progress made by each Ward in relation Ward Alliance implementation. 2. Recommendation 2.1 That the North Area Council receives an update on the progress of the Darton East, Darton West, Old Town and St Helens Ward Alliances for information purposes. Members are reminded of requirement for Ward Alliance minutes to the received by the Area Council. 3.0 Introduction 3.1 This report is set within the context of decisions made on the way the Council is structured to conduct business at Area, Ward and Neighbourhood levels (Cab21.11.2012/6), Devolved Budget arrangements (Cab16.1.2013/10.3), Officer Support (Cab13.2.2013/9) and Communities and Area Governance Documentation (Cab.8.5.2013/7.1). This report is submitted on that basis. 4.0 Ward Alliance Meetings 4.1 This report includes all notes of North Area Ward Alliances, received by the North Area Team, that were held during April, May and June 2021. Appendices: Darton East Ward Alliance Meeting: Appendix One Darton West Ward Alliance Meeting: Appendix Two Old Town Ward Alliance Meeting: Appendix Three St Helens Alliance Meeting: Appendix Four The reporting into the North Area Council, of the Ward Alliance notes is in line with the approved Council protocols. The notes are for information only. Officer Contact: Tel. No: Date: Rosie -

Barnsley Door to Door Information

Door 2 Door Services in Barnsley the local service that comes to you… Barnsley Dial-a-Ride booking line 01226 730 073 MARCH 2014 Traveline 01709 51 51 51 travelsouthyorkshire.com/door2door Contents The service The service ..................................................3 No matter what age you are, if you find it How do I register? ........................................5 difficult to use standard public transport then Booking ......................................................6 you can apply to use a Door 2 Door service Operating times and fares ...........................12 instead. Shopper Bus timetable ...............................14 Door 2 Door services are designed for people Accessibility ..............................................23 who cannot use standard public transport. Each Contact details ..........................................24 service will pick you up from your home and can take you around your local area and beyond. Door 2 Door is great for meeting new people, “Door 2 Door services are vital for many who making new friends and being able to visit would otherwise be housebound. South places you couldn’t get to before. Yorkshire Integrated Transport Authority is If you want to travel to the town centre or a local proud to support Door 2 Door as a key part of supermarket, Shopper Bus is the best service our transport network.” for you. It offers transport from your home at Cllr Jameson - Chair of the South Yorkshire certain times and on set days. Please see the Integrated Transport Authority timetable on page 14 for details. If you need to travel at a particular time, and to a destination not available on Shopper Bus (for What’s changed? example, if you are visiting a friend in hospital, or travelling to an evening class) then Dial-a- Ride or Community Car services will suit your needs better.