The Model Screenwriter – a Comedy Case Study

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Undergraduate Dissertation Trabajo Fin De Grado

Undergraduate Dissertation Trabajo Fin de Grado “Hell is a Teenage Girl”: Female Monstrosity in Jennifer's Body Author Victoria Santamaría Ibor Supervisor Maria del Mar Azcona Montoliú FACULTY OF ARTS 2020 TABLE OF CONTENTS 1. INTRODUCTION……………………………………………………………….1 2. FEMALE MONSTERS………………………………………………………….3 3. JENNIFER’S BODY……………………………………………………………..8 3.1. A WOMAN’S SACRIFICE…………………………………………………8 3.2. “SHE IS ACTUALLY EVIL, NOT HIGH SCHOOL EVIL”: NEOLIBERAL MONSTROUS FEMININITY……………………………………………..13 3.3. MEAN MONSTERS: FEMALE COMPETITION AS SOURCE OF MONSTROSITY…………………………………………………………..18 4. CONCLUSION………………………………………………………………...24 5. WORKS CITED………………………………………………………………..26 6. FILMS CITED………………………………………………………………….29 1. INTRODUCTION Jennifer’s Body, released in 2009, is a teen horror film directed by Karyn Kusama and written by Diablo Cody. It stars Megan Fox and Amanda Seyfried, playing Jennifer, the archetypal popular girl, and Anita “Needy,” her co-dependent best friend, respectively. Jennifer is a manipulative and overly sexual teenager who, as the result of a satanic ritual, is possessed by a demon and starts devouring her male classmates. Knowing that her friend is a menace, Needy decides she has to stop her. The marketing strategy behind Jennifer’s Body capitalized on Megan Fox’s emerging status as a sex symbol after her role in Transformers (dir. Michael Bay, 2007), as can be seen in the promotional poster (see fig. 1) and in the official trailer, in which Jennifer is described as the girl “every guy would die for.” The movie, which was a flop at the time of its release (grossing only $31.6 million worldwide for a film made on a $16 million Figure 1: Promotional poster budget) was criticised by some reviewers for not giving its (male) audience what it promised. -

A Producer's Handbook

DEVELOPMENT AND OTHER CHALLENGES A PRODUCER’S HANDBOOK by Kathy Avrich-Johnson Edited by Daphne Park Rehdner Summer 2002 Introduction and Disclaimer This handbook addresses business issues and considerations related to certain aspects of the production process, namely development and the acquisition of rights, producer relationships and low budget production. There is no neat title that encompasses these topics but what ties them together is that they are all areas that present particular challenges to emerging producers. In the course of researching this book, the issues that came up repeatedly are those that arise at the earlier stages of the production process or at the earlier stages of the producer’s career. If not properly addressed these will be certain to bite you in the end. There is more discussion of various considerations than in Canadian Production Finance: A Producer’s Handbook due to the nature of the topics. I have sought not to replicate any of the material covered in that book. What I have sought to provide is practical guidance through some tricky territory. There are often as many different agreements and approaches to many of the topics discussed as there are producers and no two productions are the same. The content of this handbook is designed for informational purposes only. It is by no means a comprehensive statement of available options, information, resources or alternatives related to Canadian development and production. The content does not purport to provide legal or accounting advice and must not be construed as doing so. The information contained in this handbook is not intended to substitute for informed, specific professional advice. -

FILM-1020: Story: Pre-Production Methods and the Art of Story in Motion Media 1

FILM-1020: Story: Pre-production Methods and the Art of Story in Motion Media 1 FILM-1020: STORY: PRE-PRODUCTION METHODS AND THE ART OF STORY IN MOTION MEDIA Cuyahoga Community College Viewing: FILM-1020 : Story: Pre-production Methods and the Art of Story in Motion Media Board of Trustees: 2018-05-24 Academic Term: Fall 2021 Subject Code FILM - Film and Media Arts Course Number: 1020 Title: Story: Pre-production Methods and the Art of Story in Motion Media Catalog Description: Study dramatic theory while writing an original script. Explore cultural uses of storytelling. Take real-life scenarios and respond to them with arguments constructed by the traditional elements of drama. Learn to write outlines, log lines, treatments, and character descriptions. Discuss facets of pre-production. Introduction to organizational tools and techniques used in film industry to prepare a script for production. Credit Hour(s): 3 Lecture Hour(s): 2 Lab Hour(s): 3 Requisites Prerequisite and Corequisite ENG-0995 Applied College Literacies, or appropriate score on English Placement Test; or departmental approval. Note: ENG-0990 Language Fundamentals II taken prior to Fall 2021 will also meet prerequisite requirements. Outcomes Course Outcome(s): Apply knowledge of story structure to a written treatment for a motion media production. Objective(s): 1. Identify the theme and dramatic or persuasive intent of the story. 2. Apply the art of storytelling to achieve a communications need (motivate and persuade) by creating a script for a short commercial or public service announcement (PSA). 3. Define the phases of a production from initial concept, treatment, pre-production, production, post-production and distribution. -

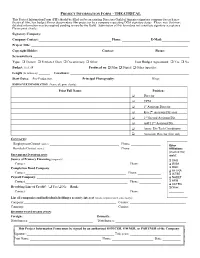

Project Information Form

PROJECT INFORMATION FORM - THEATRICAL This Project Information Form (PIF) should be filled out by an existing Directors Guild of America signatory company for each new theatrical film, low budget film or documentary film project or by a company requesting DGA signatory status. Please note that more detailed information may be required pending review by the Guild. Submission of this form does not constitute signatory acceptance. Please print clearly: Signatory Company: _________________________________________________________________________________________ Company Contact: ____________________________________________ Phone : _________________ E-Mail: _________________ Project Title: _______________________________________________________________________________________________ Copyright Holder: _______________________________________ Contact: ________________________ Phone: _______________ Screenwriter/s :_______________________________________________________________________________________________ Type: Feature Freelance Short Documentary Other:______________________ Low Budget Agreement : Yes No Budget: (U.S. ) $ ________________________________ Produced on : Film Digital Other (specify):__________________ Length (in minutes) : _______ Location/s: ________________________________________________________________________ Start Dates: Pre-Production:________________ Principal Photography :____________________ Wrap: _________________ EMPLOYEE INFORMATION (Name all, print clearly) : Print Full Name: Position: ‘ Director ‘ UPM ‘ -

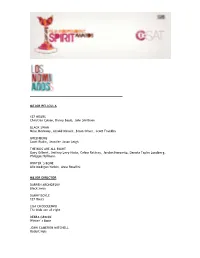

MEJOR PELICULA 127 HOURS Christian Colson, Danny Boyle

MEJOR PELICULA 127 HOURS Christian Colson, Danny Boyle, John Smithson BLACK SWAN Mike Medavoy, Arnold Messer, Brian Oliver, Scott Franklin GREENBERG Scott Rudin, Jennifer Jason Leigh THE KIDS ARE ALL RIGHT Gary Gilbert, Jeffrey Levy-Hinte, Celine Rattray, Jordan Horowitz, Daniela Taplin Lundberg, Philippe Hellmann WINTER´S BONE Alix Madigan-Yorkin, Anne Rosellini MEJOR DIRECTOR DARREN ARONOFSKY Black Swan DANNY BOYLE 127 Hours LISA CHODOLENKO The Kids are all right DEBRA GRANIK Winter´s Bone JOHN CAMERON MITCHELL Rabbit Hole MEJOR ÓPERA PRIMA EVERYTHING STRANGE AND NEW Frazer Bradshaw, Laura Techera Francia, A.D Liano GET LOW Aaron Schneider, Dean Zanuck, David Gundlach THE LAST EXORCISM Daniel Stamm, Eric Newman, Eli Roth, Marc Abraham, Thomas A. Bliss NIGHT CATCHES US Tanya Hamilton, Ronald Simons, Sean Costello, Jason Orans TINY FURNITURE Lena Dunham, Kyle Martin, Alicia Van Couvering PREMIO JOHN CASSAVETES DADDY LONGLEGS Josh Safdie, Benny Safdie, Casey Neistat, Tom Scott THE EXPLODING GIRL Bradley Rust Gray, So Yong Kim, Karin Chien, Ben Howe LBS Matthew Bonifacio, Carmine Famiglietti LOVERS OF HATE Bryan Poyser, Megan Gilbride OBSELIDIA Diane Bell, Chris Byrne, Matthew Medlin MEJOR GUIÓN LISA CHOLODENKO, STUART BLUMBERG The Kids are all right DEBRA GRANIK, ANNE ROSELLINI Winter´s Bone NICOLE HOLOFCENER Please Give DAVID LINDSAY-ABAIRE Rabbit Hole TODD SOLONDZ Life during wartime MEJOR GUIÓN DEBUTANTE DIANE BELL Obselidia LENA DUNHAM Tiny Furniture NIK FACKLER Lovely, Still ROBERT GLAUDINI Jack goes boating DANA ADAM SHAPIRO, EVAN M. WIENER Monogamy MEJOR ACTRIZ PROTAGÓNICA ANNETTE BENING The Kids are all right GRETA GERWIG Greenberg NICOLE KIDMAN Rabbit Hole JENNIFER LAWERENCE Winter´s Bone NATALIE PORTMAN Black Swan MICHELLE WILLIAMS Blue Valentine MEJOR ACTOR PROTAGÓNICO RONALD BRONSTEIN Daddy Longlegs AARON ECKHART Rabbit Hole JAMES FRANCO 127 Hours JOHN C. -

Summer 2019 Vol.21, No.3 Screenwriter Film | Television | Radio | Digital Media

CANADIAN CANADA $7 SUMMER 2019 VOL.21, NO.3 SCREENWRITER FILM | TELEVISION | RADIO | DIGITAL MEDIA A Rock Star in the Writers’ Room: Bringing Jann Arden to the small screen Crafting Canadian Horror Stories — and why we’re so good at it Celebrating the 23rd annual WGC Screenwriting Awards Emily Andras How she turned PM40011669 Wynonna Earp into a fan phenomenon Congratulations to Emily Andras of SPACE’s Wynonna Earp, Sarah Dodd of CTV’s Cardinal, and all of the other 2019 WGC Screenwriting Award winners. Proud to support Canada’s creative community. CANADIAN SCREENWRITER The journal of the Writers Guild of Canada Vol. 21 No. 3 Summer 2019 ISSN 1481-6253 Publication Mail Agreement Number 400-11669 Publisher Maureen Parker Editor Tom Villemaire [email protected] Contents Director of Communications Lana Castleman Cover Editorial Advisory Board There’s #NoChill When it Comes Michael Amo to Emily Andras’s Wynonna Earp 6 Michael MacLennan How 2019’s WGC Showrunner Award winner Emily Susin Nielsen Andras and her room built a fan and social media Simon Racioppa phenomenon — and why they’re itching to get back in Rachel Langer the saddle for Wynonna’s fourth season. President Dennis Heaton (Pacific) By Li Robbins Councillors Michael Amo (Atlantic) Features Mark Ellis (Central) What Would Jann Do? 12 Marsha Greene (Central) That’s exactly the question co-creators Leah Gauthier Alex Levine (Central) and Jennica Harper asked when it came time to craft a Anne-Marie Perrotta (Quebec) heightened (and hilarious) fictional version of Canadian Andrew Wreggitt (Western) icon Jann Arden’s life for the small screen. -

COMITINI, Mariela

MARIELA COMITINI FIRST ASSISTANT DIRECTOR FEATURES TICK TICK … BOOM! Netflix Prod: Brian Grazer, Ron Howard Dir: Lin-Manuel Miranda IF BEALE STREET COULD TALK Plan B Prod: Jeremy Kleiner, Dede Gardner Dir: Barry Jenkins *Official Selection – New York Film Festival, 2018 Adele Romanski, Megan Ellison *Official Selection – Best Motion Picture, Drama – Golden Globes, 2019 Caroline Jaczko WIDOWS Film4/New Regency Prod: Iain Canning, Emile Sherman Dir: Steve McQueen *Official Selection – Toronto Film Festival, 2018 Amy Jackson STRONGER Lionsgate Prod: Todd Lieberman, Jeff Stott Dir: David Gordon Green Nicolas Stern CONFIRMATION HBO Prod: Susannah Grant, Michael London Dir: Rick Famuyiwa Kerry Washington THE LIGHT BETWEEN THE OCEANS Dreamworks SKG Prod: Rosie Alison, Jeffrey Clifford Dir: Derek Cianfrance MISSISSIPPI GRIND Sycamore Pictures Prod: Randall Emmett, John Lesher Dir: Anna Boden Jeremy Kipp Walker Ryan Fleck SHE’S FUNNY THAT WAY Lagniappe Films Prod: Wes Anderson, Robert Barnum Dir: Peter Bogdanovich Noah Baumbach LOST RIVER Bold Films/Warner Bros. Prod: Noaz Deshe, Gary Michael Walters Dir: Ryan Gosling Ryan Gosling KRISTY Dimension Films Prod: Scott Derrickson,Robert Kravis, Mattew Stein Dir: Oliver Blackburn BEGIN AGAIN The Weinstein Company Prod: Sam Hoffman, Tom Rice, Molly Smith Dir: John Carney PARADISE Mandate Pictures Prod: Diablo Cody, Nathan Kahane Dir: Diablo Cody THE PLACE BEYOND THE PINES Focus Features Prod: Matt Berenson, Jim Tauber, Sydney Kimmel Dir: Derek Cianfrance THE ORANGES ATO Pictures Prod: Stefanie Azpiazu, -

Canadian Canada $7 Spring 2020 Vol.22, No.2 Screenwriter Film | Television | Radio | Digital Media

CANADIAN CANADA $7 SPRING 2020 VOL.22, NO.2 SCREENWRITER FILM | TELEVISION | RADIO | DIGITAL MEDIA The Law & Order Issue The Detectives: True Crime Canadian-Style Peter Mitchell on Murdoch’s 200th ep Floyd Kane Delves into class, race & gender in legal PM40011669 drama Diggstown Help Producers Find and Hire You Update your Member Directory profile. It’s easy. Login at www.wgc.ca to get started. Questions? Contact Terry Mark ([email protected]) Member Directory Ad.indd 1 3/6/19 11:25 AM CANADIAN SCREENWRITER The journal of the Writers Guild of Canada Vol. 22 No. 2 Spring 2020 Contents ISSN 1481-6253 Publication Mail Agreement Number 400-11669 Cover Publisher Maureen Parker Diggstown Raises Kane To New Heights 6 Editor Tom Villemaire [email protected] Creator and showrunner Floyd Kane tackles the intersection of class, race, gender and the Canadian legal system as the Director of Communications groundbreaking CBC drama heads into its second season Lana Castleman By Li Robbins Editorial Advisory Board Michael Amo Michael MacLennan Features Susin Nielsen The Detectives: True Crime Canadian-Style 12 Simon Racioppa Rachel Langer With a solid background investigating and writing about true President Dennis Heaton (Pacific) crime, showrunner Petro Duszara and his team tell us why this Councillors series is resonating with viewers and lawmakers alike. Michael Amo (Atlantic) By Matthew Hays Marsha Greene (Central) Alex Levine (Central) Anne-Marie Perrotta (Quebec) Murdoch Mysteries’ Major Milestone 16 Lienne Sawatsky (Central) Andrew Wreggitt (Western) Showrunner Peter Mitchell reflects on the successful marriage Design Studio Ours of writing and crew that has made Murdoch Mysteries an international hit, fuelling 200+ eps. -

Why Hollywood Isn't As Liberal As We Think and Why It Matters

Claremont Colleges Scholarship @ Claremont CMC Senior Theses CMC Student Scholarship 2019 Why Hollywood Isn't As Liberal As We Think nda Why It Matters Amanda Daily Claremont McKenna College Recommended Citation Daily, Amanda, "Why Hollywood Isn't As Liberal As We Think nda Why It Matters" (2019). CMC Senior Theses. 2230. https://scholarship.claremont.edu/cmc_theses/2230 This Open Access Senior Thesis is brought to you by Scholarship@Claremont. It has been accepted for inclusion in this collection by an authorized administrator. For more information, please contact [email protected]. 1 Claremont McKenna College Why Hollywood Isn’t As Liberal As We Think And Why It Matters Submitted to Professor Jon Shields by Amanda Daily for Senior Thesis Fall 2018 and Spring 2019 April 29, 2019 2 3 Abstract Hollywood has long had a reputation as a liberal institution. Especially in 2019, it is viewed as a highly polarized sector of society sometimes hostile to those on the right side of the aisle. But just because the majority of those who work in Hollywood are liberal, that doesn’t necessarily mean our entertainment follows suit. I argue in my thesis that entertainment in Hollywood is far less partisan than people think it is and moreover, that our entertainment represents plenty of conservative themes and ideas. In doing so, I look at a combination of markets and artistic demands that restrain the politics of those in the entertainment industry and even create space for more conservative productions. Although normally art and markets are thought to be in tension with one another, in this case, they conspire to make our entertainment less one-sided politically. -

Feature Films

MARCELO ZARVOS AWARDS/NOMINATIONS CINEMA BRAZIL GRAND PRIZE FLORES RARAS NOMINATION (2014) Best Original Music ONLINE FILM & TELEVISION PHIL SPECTOR ASSOCIATION AWARD NOMINATION (2013) Best Music in a Non-Series BLACK REEL AWARDS BROOKLYN’S FINEST NOMINATION (2011) Best Original Score EMMY AWARD NOMINATION YOU DON’T KNOW JACK (2010) Music Composition For A Miniseries, Movie or Special (Dramatic Underscore) EMMY AWARD NOMINATION TAKING CHANCE (2009) Music Composition For A Miniseries, Movie or Special (Dramatic Underscore) BRAZILIA FESTIVAL OF UMA HISTÓRIA DE FUTEBOL BRAZILIAN CINEMA AWARD (1998) 35mm Shorts- Best Music FEATURE FILMS MAPPLETHORPE Eliza Dushku, Nate Dushku, Ondi Timoner, Richard J. Interloper Films Bosner, prods. Ondi Timoner, dir. THE CHAPERONE Kelly Carmichael, Rose Ganguzza, Elizabeth McGovern, Anonymous Content Gary Hamilton, prods. Michael Engler, dir. BEST OF ENEMIES Tobey Maguire, Matt Berenson, Matthew Plouffe, Danny Netflix / Likely Story Strong, prods. Robin Bissell, dir. The Gorfaine/Schwartz Agency, Inc. (818) 260-8500 1 MARCELO ZARVOS LAND OF STEADY HABITS Nicole Holofcener, Anthony Bregman, Stefanie Azpiazu, Netflix / Likely Story prods. Nicole Holofcener, dir. WONDER David Hoberman, Todd Lieberman, prods. Lionsgate Stephen Chbosky, dir. FENCES Scott Rudin, Denzel Washington, prods. Paramount Pictures Denzel Washington, dir. ROCK THE KASBAH Steve Bing, Bill Block, Mitch Glazer, Jacob Pechenik, Open Road Films Ethan Smith, prods. Barry Levinson, dir. OUR KIND OF TRAITOR Simon Cornwell, Stephen Cornwell, Gail Egan, prods. The Ink Factory Susanna White, dir. AMERICAN ULTRA David Alpert, Anthony Bregman, Kevin Scott Frakes, Lionsgate Britton Rizzio, prods. Nima Nourizadeh, dir. THE CHOICE Theresa Park, Peter Safran, Nicholas Sparks, prods. Lionsgate Ross Katz, dir. CELL Michael Benaroya, Shara Kay, Richard Saperstein, Brian Benaroya Pictures Witten, prods. -

RTV 3101 (Fall 2018) ADVANCED WRITING for the ELECTRONIC MEDIA Instructor: Genevieve Curtis, M.A. Office: Weimer Hall #3065

RTV 3101 (Fall 2018) ADVANCED WRITING FOR THE ELECTRONIC MEDIA Instructor: Genevieve Curtis, M.A. Office: Weimer Hall #3065 Office Phone: 347-712-0583 e-mail: [email protected] (I prefer you use Canvas for communication) Lecture: Tuesday 5:10-6p. Thursday 4:05-6p. Office Hours: Tuesday after class, Thursday after class; and by appointment Description of Course This course is designed to provide a thorough understanding and overview of the principles of scriptwriting, and to learn to apply these principles through practical exercises in various programs: commercials, sponsored and corporate videos, television and film documentaries, fictional works and adaptations. Another major objective is to help develop the students' critical faculties, enabling them to better examine and evaluate the scripts of others, as well as their own. Students should expect to have a completed short script by the end of semester. There will be a rubric for grading scripts. The course will be comprised of lectures, exercises, screenings, workshops, analyses, and discussions. Grading Participation 5pt Story 50 Words or Less 5pt Commercial/PSA 5pt Documentary pitch 5pt Documentary critique 5pt Stop Motion Animation 5pt TV Pitch 5pt TV critique I 5pt TV critique II 5pt Experimental pitch 5pt Experimental critique 5pt Adaptations critique 5pt Script Mark-up 10pt Quiz 10pt Drama Script Analysis 10pt Comedy Short Script 10pt Horror Short Script 10pt Drama Short Script 20pt Exam 20pt Punctuality is most important in this industry. Late assignments will be penalized by one letter grade (i.e., 10%) per day. Students are expected to attend and participate in all classes. -

Cruel Auteurism Affective Digital Mediations Toward Film-Composition Bonnie Lenore Kyburz

Cruel Auteurism affective digital mediations toward film-composition bonnie lenore kyburz CRUEL AUTEURISM AFFECTIVE DIGITAL MEDIATIONS TOWARD FILM-COMPOSITION #WRITING Series Editor: Cheryl E. Ball The# writing series publishes open-access digital and low-cost print editions of monographs that address issues in digital rhetoric, new media studies, dig- ital humanities, techno-pedagogy, and similar areas of interest. The WAC Clearinghouse, Colorado State University Open Press, and the Uni- versity Press of Colorado are collaborating so that books in this series are widely available through free digital distribution and in a low-cost print edi- tion. The publishers and the series editor are committed to the principle that knowledge should freely circulate. We see the opportunities that new technol- ogies have for further democratizing knowledge. And we see that to share the power of writing is to share the means for all to articulate their needs, interest, and learning into the great experiment of literacy. Other Books in the Series Derek N. Mueller, Network Sense: Methods for Visualizing a Discipline (2017) CRUEL AUTEURISM AFFECTIVE DIGITAL MEDIATIONS TOWARD FILM-COMPOSITION By bonnie lenore kyburz The WAC Clearinghouse wac.colostate.edu Fort Collins, Colorado University Press of Colorado upcolorado.com Louisville, Colorado The WAC Clearinghouse, Fort Collins, Colorado 80523 University Press of Colorado, Lousville, Colorado 80027 © 2019 by bonnie lenore kyburz. This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribu- tion-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International. ISBN 978-1-64215-002-5 (PDF) | 978-1-64215-018-6 (ePub) | 978-1-60732-918-3 (pbk.) Printed in the United States of America Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Names: Kyburz, Bonnie Lenore, author.