Robert E. Lee and Slavery Allen C

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

William Preston and the Revolutionary Settlement

Journal of Backcountry Studies EDITOR’S NOTE: This is the third and last installment of the author’s 1990 University of Maryland dissertation, directed by Professor Emory Evans, to be republished in JBS. Dr. Osborn is President of Pacific Union College. William Preston and the Revolutionary Settlement BY RICHARD OSBORN Patriot (1775-1778) Revolutions ultimately conclude with a large scale resolution in the major political, social, and economic issues raised by the upheaval. During the final two years of the American Revolution, William Preston struggled to anticipate and participate in the emerging American regime. For Preston, the American Revolution involved two challenges--Indians and Loyalists. The outcome of his struggles with both groups would help determine the results of the Revolution in Virginia. If Preston could keep the various Indian tribes subdued with minimal help from the rest of Virginia, then more Virginians would be free to join the American armies fighting the English. But if he was unsuccessful, Virginia would have to divert resources and manpower away from the broader colonial effort to its own protection. The other challenge represented an internal one. A large number of Loyalist neighbors continually tested Preston's abilities to forge a unified government on the frontier which could, in turn, challenge the Indians effectivel y and the British, if they brought the war to Virginia. In these struggles, he even had to prove he was a Patriot. Preston clearly placed his allegiance with the revolutionary movement when he joined with other freeholders from Fincastle County on January 20, 1775 to organize their local county committee in response to requests by the Continental Congress that such committees be established. -

Memorial Service in Honor of William Preston

WILLIAM PRESTON JOHNSTON, /WEMORIAL SERVICE IN HONOR OF William Preston Johnston, LLD. FIRST PRESIDENT OP TULANE UNIVERSITY. 1884-1899 INTRODUCTORY ADDRESS BY JUDGE CHARLES E. EEININER iWE/nORIAL ORATIOIN BY B. M. PALMER. D. D. IN MEMORIAM. T^HE audience being assembled in Tulane Hall on the evening of December 20th, 1899, the services were opened by the Rt. Rev. Davis Sessums, D. D., who offered the following PRAYER: Let the words of my mouth, and the meditation of my heart, be always acceptable in Thy sight, O Lord, my strength and my redeemer. So teach us to number our days, that we may apply our hearts unto wisdom. O God, the Sovereign Lord and King, who hast given unto men the administration of government upon earth, we make our supplications unto Thee, for all those who have that trust committed to their hands. Enable them, we pray Thee, to fulfil the same to Thy honor and the welfare of the nations among whom they rule. Especially we implore Thy favor on Thy servants, the President of the United States, the Governor of this State, and all who have the making or executing of law in the land. Endue them with uprightness and wisdom, with firmness and clemency, remembering whose ministers they are, and the account which they must render at Thy throne. To the people of all ranks and conditions among us, give the spirit of obedience to government, and of contentment under its protection, in leading peaceable and honest lives. Let the righteousness prevail which exalteth a nation, and throughout our land let the name of Thy Son be acknowledged as King of Kings, and Lord of Lords, to Thy honor and glory, who art God over all, blessed for evermore. -

The Shadow of Napoleon Upon Lee at Gettysburg

Papers of the 2017 Gettysburg National Military Park Seminar The Shadow of Napoleon upon Lee at Gettysburg Charles Teague Every general commanding an army hopes to win the next battle. Some will dream that they might accomplish a decisive victory, and in this Robert E. Lee was no different. By the late spring of 1863 he already had notable successes in battlefield trials. But now, over two years into a devastating war, he was looking to destroy the military force that would again oppose him, thereby assuring an end to the war to the benefit of the Confederate States of America. In the late spring of 1863 he embarked upon an audacious plan that necessitated a huge vulnerability: uncovering the capital city of Richmond. His speculation, which proved prescient, was that the Union army that lay between the two capitals would be directed to pursue and block him as he advanced north Robert E. Lee, 1865 (LOC) of the Potomac River. He would thereby draw it out of entrenched defensive positions held along the Rappahannock River and into the open, stretched out by marching. He expected that force to risk a battle against his Army of Northern Virginia, one that could bring a Federal defeat such that the cities of Philadelphia, Baltimore, or Washington might succumb, morale in the North to continue the war would plummet, and the South could achieve its true independence. One of Lee’s major generals would later explain that Lee told him in the march to battle of his goal to destroy the Union army. -

Mrs. General Lee's Attempts to Regain Her Possessions After the Cnil War

MRS. GENERAL LEE'S ATTEMPTS TO REGAIN HER POSSESSIONS AFTER THE CNIL WAR By RUTH PRESTON ROSE When Mary Custis Lee, the wife of Robert E. Lee, left Arlington House in May of 1861, she removed only a few of her more valuable possessions, not knowing that she would never return to live in the house which had been home to her since her birth in 1808. The Federal Army moved onto Mrs. Lee's Arling ton estate on May 25, 1861. The house was used as army headquarters during part of the war and the grounds immediately around the house became a nation al cemetery in 1864. Because of strong anti-confederate sentiment after the war, there was no possibility of Mrs. Lee's regaining possession of her home. Restora tion of the furnishings of the house was complicated by the fact that some articles had been sent to the Patent Office where they were placed on display. Mary Anna Randolph Custis was the only surviving child of George Washing ton Parke Custis and Mary Lee Fitzhugh. Her father was the grandson of Martha Custis Washington and had been adopted by George Washington when his father, John Custis, died during the Revolutionary War. The child was brought up during the glorious days of the new republic, living with his adopted father in New York and Philadelphia during the first President's years in office and remaining with the Washingtons during their last years at Mount Vernon. In 1802, after the death of Martha Washington, young Custis started building Arlington House on a hill overlooking the new city of Washington. -

Reinterpreting Robert E. Lee Through His Life at Arlington House

University of New Hampshire University of New Hampshire Scholars' Repository Master's Theses and Capstones Student Scholarship Fall 2020 The House That Built Lee: Reinterpreting Robert E. Lee Through his Life at Arlington House Cecilia Paquette University of New Hampshire, Durham Follow this and additional works at: https://scholars.unh.edu/thesis Recommended Citation Paquette, Cecilia, "The House That Built Lee: Reinterpreting Robert E. Lee Through his Life at Arlington House" (2020). Master's Theses and Capstones. 1393. https://scholars.unh.edu/thesis/1393 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Scholarship at University of New Hampshire Scholars' Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Master's Theses and Capstones by an authorized administrator of University of New Hampshire Scholars' Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. THE HOUSE THAT BUILT LEE Reinterpreting Robert E. Lee Through his Life at Arlington House BY CECILIA PAQUETTE BA, University of Massachusetts, Boston, 2017 BFA, Massachusetts College of Art and Design, 2014 THESIS Submitted to the University of New Hampshire in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts in History September, 2020 ALL RIGHTS RESERVED © 2020 Cecilia Paquette ii This thesis was examined and approved in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master in History by: Thesis Director, Jason Sokol, Associate Professor, History Jessica Lepler, Associate Professor, History Kimberly Alexander, Lecturer, History On August 14, 2020 Approval signatures are on file with the University of New Hampshire Graduate School. !iii to Joseph, for being my home !iv ACKNOWLEDGMENTS First and foremost, I would like to thank my advisory committee at the University of New Hampshire. -

The Florida Historical Quarterly Volume Xlvi April 1968 Number 4

A PRIL 1968 Published by THE FLORIDA HISTORICAL SOCIETY THE FLORIDA HISTORICAL SOCIETY THE HISTORICAL SOCIETY OF FLORIDA, 1856 THE FLORIDA HISTORICAL SOCIETY, successor, 1902 THE FLORIDA HISTORICAL SOCIETY, incoporated, 1905 by GEORGE R. FAIRBANKS, FRANCIS P. FLEMING, GEORGE W. WILSON, CHARLES M. COOPER, JAMES P. TALIAFERRO, V. W. SHIELDS, WILLIAM A. BLOUNT, GEORGE P. RANEY. OFFICERS WILLIAM M. GOZA, president HERBERT J. DOHERTY, JR., 1st vice president JAMES C. CRAIG, 2nd vice president PAT DODSON, recording secretary MARGARET L. CHAPMAN, executive secretary SAMUEL PROCTOR, editor D IRECTORS ROBERT H. AKERMAN MILTON D. JONES CHARLES O. ANDREWS, JR. FRANK J. LAUMER MRS. T. O. BRUCE JAMES H. LIPSCOMB, III JAMES D. BRUTON, JR. WILLIAM WARREN ROGERS AUGUST BURGHARD JAMES A. SERVIES MRS. HENRY J. BURKHARDT CHARLTON W. TEBEAU WALTER S. HARDIN JULIAN I. WEINKLE JAMES R. KNOTT, ex-officio (All correspondence relating to Society business, memberships, and Quarterly subscriptions should be addressed to Miss Margaret Chapman, University of South Florida Library, Tampa, Florida 33620. Articles for publication, books for review, and editorial correspondence should be ad- dressed to the Quarterly, Box 14045, University Station, Gainesville, Florida, 32601.) * * * To explore the field of Florida history, to seek and gather up the ancient chronicles in which its annals are contained, to retain the legendary lore which may yet throw light upon the past, to trace its monuments and remains to elucidate what has been written to disprove the false and support the true, to do justice to the men who have figured in the olden time, to keep and preserve all that is known in trust for those who are to come after us, to increase and extend the knowledge of our history, and to teach our children that first essential knowledge, the history of our State, are objects well worthy of our best efforts. -

Student Life at Western Military Institute William Preston Johnstons

STUDENT LIFE AT WESTERN MILITARY INSTITUTE: WILLIAM PRESTON JOHNSTON'S JOURNAL, 1847-1848 T•sc,amEu BY ABTHUa M•mv•r SHAW Centenary College of Louisiana, Skreveport Author of william Preston lohnston (1948) INTRODUCTION. William Preston Johnston, the oldest son of Albert Sidney Johnston and his wife, Henrietta Preston, was born in Louisville, Kentucky, on January 5, 1831. His mother died when he was less than five years old; and a year later his father left Kentucky for Texas, leaving his son and a four-year-old daughter, Henrietta Preston, in the care of some of their maternal relatives. The boy resided for several years in the home of his mother's youngest sister, Mrs. Josephine Rogers; and after her death in November, 1842, his further rearing was entrusted to his uncle, William Preston.' As a soldier in Texas, Albert Sidney Johnston rendered valuable service to the young republic, rose to the rank of brigadier general, and served as Secretary of War under Presi- dent Mirabeau B. Lamar.* During a visit to Kentucky in October, 1843, General Johnston married Eliza Grifl•n, a cousin of his first wife, took his bride to Texas, and settled on a plan- tation which he had purchased in Brazoria County near Gal-' veston. 3 From this union six children were born;" but his affee- tion for his oldest children, from whom he was separated most of the time, remained undiminished. William was deeply de- voted to his father, and one of the brightest spots in his boy- hood was a visit he made early in 1847 to China Grove, his father's plantation, which was really a large undeveloped tract of land. -

Collection in Civil War Medicine

Collection in Civil War Medicine AUTHOR TITLE PUBLICATION INFO NOTES Adams, George Doctors in blue: the medical history of New York: Henry Schuman, Worthington the Union Army in the Civil War c1952. Allen, B. W. Confederate hospital reports [Charlottesville, VA: B. W. Allen, Two manuscript albums, covering a portion of 1864] 1862, the whole of 1863, and a part of 1864 in Charlottesville, VA, giving case histories of soldiers injured in the field, 2 p. at end of v.1. American Journal of Pharmacy Philadelphia: Merrihew and Library has 1859-1865. Also 1853-1870 are Thompson available on microfilm. The ambulance system: reprinted Boston: Crosby and Nichols, from the North American Review, 1864 January, 1864, and published, for gratuitous distribution, by the committee of citizens who have in charge the sending of petitions to Congress for the establishment of a thorough and uniform ambulance system in the armies of the Republic Anderson, Galusha The story of Aunt Lizzie Aiken Chicago: Ellen M. Sprague, 1880 6th edition. Andrews, Matthew Page, The women of the South in war times Baltimore: The Norman, New edition revised. ed. Remington Co., 1927 [c1920] Apperson, John Samuel; Repairing the "March of Mars:" the Macon, GA: Mercer University Apperson was a hospital steward in the John Herbert Roper, ed. Civil War diaries of John Samuel Press, 2001 Stonewall Brigade, 1861-1865. Apperson 1 Bibliography was last updated in January, 2015. Collection in Civil War Medicine Appia, P. Louis, 1818- The ambulance surgeon or practical Edinburgh: Adam and Charles A popular manual for Civil War surgeons in 1898 observations on gunshot wounds Black, 1862 America, helpful for both its discussion of gunshot wounds and the use of the ambulance. -

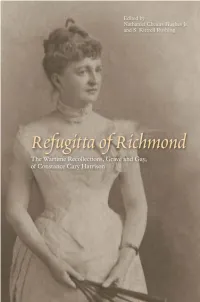

The Wartime Recollections, Grave and Gay, of Constance Cary Harrison / Edited, Annotated, and with an Introduction by Nathaniel Cheairs Hughes Jr

Refugitta of Richmond RefugittaThe Wartime Recollections, of Richmond Grave and Gay, of Constance Cary Harrison Edited by Nathaniel Cheairs Hughes Jr. and S. Kittrell Rushing The University of Tennessee Press • Knoxville a Copyright © 2011 by The University of Tennessee Press / Knoxville. All Rights Reserved. Manufactured in the United States of America. First Edition. Originally published by Charles Scribner’s Sons, 1916. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Harrison, Burton, Mrs., 1843–1920. Refugitta of Richmond: the wartime recollections, grave and gay, of Constance Cary Harrison / edited, annotated, and with an introduction by Nathaniel Cheairs Hughes Jr. and S. Kittrell Rushing. — 1st ed. p. cm. Originally published under title: Recollections grave and gay. New York: Charles Scribner’s Sons, 1911. Includes bibliographical references and index. eISBN-13: 978-1-57233-792-3 eISBN-10: 1-57233-792-3 1. Harrison, Burton, Mrs., 1843–1920. 2. United States—History—Civil War, 1861–1865—Personal narratives, Confederate. 3. Virginia—History—Civil War, 1861–1865—Personal narratives, Confederate. 4. United States—History—Civil War, 1861–1865—Women. 5. Virginia—History—Civil War, 1861–1865—Women. 6. Richmond (Va.)—History—Civil War, 1861–1865. I. Hughes, Nathaniel Cheairs. II. Rushing, S. Kittrell. III. Harrison, Burton, Mrs., 1843-1920 Recollections grave and gay. IV. Title. E487.H312 2011 973.7'82—dc22 20100300 Contents Preface ............................................. ix Acknowledgments .....................................xiii -

“We Have Lived & Loved As Brothers”: Male Friendship at the University of Virginia 1825- 1861 Josh Morrison Masters'

“We Have Lived & Loved as Brothers”: Male Friendship at the University of Virginia 1825- 1861 Josh Morrison Masters’ Thesis April 25, 2017 Introduction & Historiography ....................................................................................................... 2 Part I: The Students and their University ....................................................................................... 8 Part II: Autograph Albums: A Language of Friendship .................................................................. 23 Part III: What Does Honor Have to Do with It? Explaining Violence & Friendship ....................... 40 Conclusion: Friendship & War ...................................................................................................... 48 1 INTRODUCTION & HISTORIOGRAPHY During the late antebellum period, the University of Virginia was widely regarded as the premier institution of Southern learning. Its student body was composed almost exclusively of the favored sons of the richest and most influential men of the region. As such, Jefferson’s University served not only as a mirror reflecting elite Southern culture but as an active agent of its ideological, and social development. Its first years saw a litany of violent outbursts that drew much comment at the time and indeed much focus even today. While Thomas Jefferson and the early professors did their best to get the institution off the ground, a casual observer could be excused for thinking that many of its students were just as fervently trying to tear it down brick -

Documenting Women's Lives

Documenting Women’s Lives A Users Guide to Manuscripts at the Virginia Historical Society A Acree, Sallie Ann, Scrapbook, 1868–1885. 1 volume. Mss5:7Ac764:1. Sallie Anne Acree (1837–1873) kept this scrapbook while living at Forest Home in Bedford County; it contains newspaper clippings on religion, female decorum, poetry, and a few Civil War stories. Adams Family Papers, 1672–1792. 222 items. Mss1Ad198a. Microfilm reel C321. This collection of consists primarily of correspondence, 1762–1788, of Thomas Adams (1730–1788), a merchant in Richmond, Va., and London, Eng., who served in the U.S. Continental Congress during the American Revolution and later settled in Augusta County. Letters chiefly concern politics and mercantile affairs, including one, 1788, from Martha Miller of Rockbridge County discussing horses and the payment Adams's debt to her (section 6). Additional information on the debt appears in a letter, 1787, from Miller to Adams (Mss2M6163a1). There is also an undated letter from the wife of Adams's brother, Elizabeth (Griffin) Adams (1736–1800) of Richmond, regarding Thomas Adams's marriage to the widow Elizabeth (Fauntleroy) Turner Cocke (1736–1792) of Bremo in Henrico County (section 6). Papers of Elizabeth Cocke Adams, include a letter, 1791, to her son, William Cocke (1758–1835), about finances; a personal account, 1789– 1790, with her husband's executor, Thomas Massie; and inventories, 1792, of her estate in Amherst and Cumberland counties (section 11). Other legal and economic papers that feature women appear scattered throughout the collection; they include the wills, 1743 and 1744, of Sarah (Adams) Atkinson of London (section 3) and Ann Adams of Westham, Eng. -

Combs Lawson), 1911- PAPERS, 1862-1983

State of Tennessee Department of State Tennessee State Library and Archives 403 Seventh Avenue North Nashville, Tennessee 37243-0312 FORT, COMBS L. (Combs Lawson), 1911- PAPERS, 1862-1983 Processed by: Lori D. Lockhart Archival Technical Services Accession Number: THS 867 Date Completed: September 21, 2006 Location: THS I-G-1-2 Microfilm Accession Number: 1823 MICROFILMED INTRODUCTION The Combs L. Fort Papers, 1862-1983, is centered around items that focus on Combs Lawson Fort during his time in the military in the course of World War II and on the Mt. Olivet Confederate Memorial. The Combs L. Fort Papers are a gift of Combs L. Fort of Nashville, Tennessee, and his wife, Ann Hardeman Fort. The Mt. Olivet Confederate Memorial Correspondence was given to the Tennessee Historical Society in memory of Miss Henry C. Ewin, aunt of Ann Hardeman Fort. Miss Henry C. Ewin was the secretary of the Confederate Monument Association and the niece of Col. And Mrs. John Overton. Mrs. (Col.) John Overton, Harriet V. Maxwell, was the chairman of the Confederate Monument Association at Mt. Olivet Cemetery, Nashville, Tennessee. Miss Henry C. Ewin was also the Great Granddaughter of Judge and Mrs. John Overton. Miss Ewin’s father, Col. Henry C. Ewin, of the Confederate Army, was killed at the Battle of Stones River. The materials in this collection measure 1.25 linear feet of shelf space. There are approximately 210 items and 16 volumes included in this collection. There are no restrictions on the materials. Single photocopies of unpublished writings in the Combs L. Fort Papers may be made for purposes of scholarly research.