Structural Change Or Social Fluidity? Examining Intergenerational Mobility in Education in India

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A N N U a L R E P O

A N N U A L REPORT 2011 - 2012 ANNUAL REPORT 2011-12 Contents Message from the Chairman 3 Letter from the Managing Director & CEO 5 Board of Directors & Management Team 7 Performance Dashboard 8 Report of the Board of Directors 10 Management Discussion and Analysis 23 Report on Corporate Governance 44 Balance Sheet as at 31 March 2012 58 Profit and Loss Account for the year ended 31 March 2012 59 Schedules 60 Cash Flow Statement 93 Auditors’ Report 94 Basel II - Pillar 3 Disclosures as on 31 March 2012 96 Balance Sheet Abstract and the Bank’s General Business Profile 117 Statement Pursuant to Section 212 of the Companies Act, 1956 118 Related to Subsidiary Companies Accounts of Subsidiary Company Fedbank Financial Services Limited 119 Consolidated Balance Sheet as at 31 March 2012 150 Consolidated Profit and Loss Account for the year ended 31 March 2012 151 Schedules (Consolidated) 152 Consolidated Cash Flow Statement 190 Auditors’ Report (Consolidated) 191 ANNUAL REPORT 2011-12 3 Message from the Chairman I am happy to address you all on the occasion of this 81st However, let me assure you that we need not despair. The Annual General Meeting of your Bank. 2011-12 has been Indian financial markets are more mature, diverse and another excellent year in the history of Federal Bank. I deep. They have resilience to absorb shocks. Our regulatory would like to congratulate the MD & CEO and his able team. systems and crisis response mechanisms are very robust and As you are aware, this performance has been achieved in sophisticated. -

In the High Court of Kerala at Ernakulam Present The

IN THE HIGH COURT OF KERALA AT ERNAKULAM PRESENT THE HONOURABLE MR. JUSTICE P.V.KUNHIKRISHNAN MONDAY, THE 14TH DAY OF DECEMBER 2020/ 23RD AGRAHAYANA, 1942 Bail Appl..No.8209 OF 2020 CRIME NO.1/2019 OF VACB, ERNAKULAM , Ernakulam PETITIONER: V.K.EBRAHIM KUNJU AGED 68 YEARS RESIDENT OF PERIYAR CRESCENT, BY LANE-3, SIVA TEMPLE ROAD, THOTTAKKATTUKARA, ALUVA, ERNAKULAM DISTRICT PIN-683108 BY ADVS. SRI.B.RAMAN PILLAI (SR.) SRI.M.SUNILKUMAR SRI.SUJESH MENON V.B. SRI.T.ANIL KUMAR SRI.THOMAS ABRAHAM (NILACKAPPILLIL) SRI.THOMAS SABU VADAKEKUT SHRI.MAHESH BHANU S. SMT.S.LAKSHMI SANKAR SHRI.RESSIL LONAN SRI.R.ANIL RESPONDENT: STATE OF KERALA REPRESENTED BY PUBLIC PROSECUTOR, HIGH COURT OF KERALA ERNAKULAM- 682031 BY K.V.SOHAN, STATE ATTORNEY THIS BAIL APPLICATION HAVING COME UP FOR ADMISSION ON 11-12-2020, THE COURT ON 14-12-2020 PASSED THE FOLLOWING: B.A.No.8209 of 2020 2 P.V.KUNHIKRISHNAN, J -------------------------------- B.A.No.8209 of 2020 ------------------------------- Dated this the 14th day of December 2020 O R D E R The Palarivattom flyover, which reduced the traffic problem in Cochin city to some extent, is now unpopular because of the alleged corruption in its construction. The name Palarivattom has evolved from the word 'Pagalnarivattom'. 'Pagalnarivattom' means a place where jackal roams even in the day time. Now Keralites suspect that it is not jackals but corrupt people wandering through this area. The vigilance must find out the truth by conducting a fair and impartial investigation and restore the name of Palarivattom connected with that of jackals instead of corrupt people. -

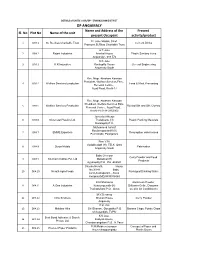

DP ANGAMALY Name and Address of the Present Sl

DETAILS of UNITS in DA/DP - ERNAKULAM DISTRICT DP ANGAMALY Name and Address of the Present Sl. No Plot No Name of the unit present Occupant activity/product Fr. Jose Madan, Chief 1 DPA 1 St. Reethas Charitable Trust Cement Bricks Promoter,St.Ritas Charitable Trust A.T.Jose 2 DPA 2 Rajani Industries Arackal House Plastic Sanitary items Angamaly - 688 572 K.K.Jose 3 DPA 3 K.K.Industries Kachapilly House General Engineering Angamaly South Rev. Msgr. Abraham Karedan President, Welfare Services Ekm., 4 DPA 4 Welfare Services Ernakulam Food & Meat Processing Renewal Centre , Azad Road, Kochi-17 Rev. Msgr. Abraham Karedan President, Welfare Services Ekm. 5 DPA 5 Welfare Services Ernakulam Reeled Silk and Silk Clothes Renewal Centre , Azad Road, Kochi-18 0484-2453962 Jameela Alikunju 6 DPA 6 Silver star Plastics Ltd. Thalakkattu (H) Plastic Packing Materials Marampilly P.O. Muhammed Ashraf Moolamaparambil (H) 7 DPA 7 EMME Exporters Resumption order issued Pulinchode, Perinjanam Binu V.M. Vadakkedath (H). TELK Qrtrs 8 DPA 8 Surya Metals Fabrication Angamaly South Babu Cheriyan Curry Powder and Food 9 DPA 9 Southern Cables Pvt. Ltd Maliakkal (H) Products Ayyampilly P.O Pin -682501 Chacko Neroth, House No.X/141, Baby 10 DPA 10 Neroth Agro Foods Packaged Drinking Water Land,Asokapuram , Aluva Korapaul(MD)9895016060 K.M.Shanavas Aluminium Powder 11 DPA 11 A One Industries Kunnumpurath (H) Diffusers Grills , Dampers Thaikattukara P.O. Aluva used in Air Conditioners M.V.Devassy 12 DPA 12 Nino Brothers Moolan House Curry Powder Angamaly P.K. Giri 13 DPA 13 Malabar Hills Giri Bhavan , Oorupoika P.O Banana Chips, Potato Chips Chirayankizh, TVPM K.K.Jose Best Bond Adhesive & Starch 14 DPA 14 Kodiyan House, Private Ltd. -

DPR-Phase 1B – SN Junction to Thripunithura

DETAILED PROJECT REPORT PHASE 1B S.N JUNCTION - TRIPUNITHURA INDEX Salient features Chapter-0 Executive Summary 0.1 Introduction 0.2 Transport demand forecast 0.3 System Selection 0.4 Civil Engineering 0.5 Train operation plan & rolling stock 0.6 Power Supply 0.7 Maintenance Depot 0.8 Environmental Impact Assessment (EIA) 0.9 Cost Estimates 0.10 Economic Analysis 0.11 Financial Analysis and Financing Plan 0.12 Implementation plan 0.13 Conclusions and Recommendations Chapter-1 Introduction 1.1 Background 1.2 Study area & population 1.3 Growth of motor vehicles 1.4 Review of relevant past studies 1.5 Phase I Metro Network in Kochi 1.6 Composition of report Chapter-2 Transport Demand Forecast 2.1 Primary traffic surveys and data analysis 2.2 Existing transportation system in the city 2.3 Future growth scenario and transport demand modeling 2.4 Transport demand model structure 2.5 Vehicle availability, generation and attraction models 2.6 AM Peak model validation 2.7 Assumptions for transport demand forecasting 2.8 Development of alternative mass transport networks 2.9 Evaluation of alternative mass transport networks 2.1 Transport demand forecast for revised phase II Mass Transport 2.11 Summary of transport demand forecast for revised phase II mass Chapter-3 System Selection 3.1 Permanent way 3.2 Rolling stock 3.3 Traction system 3.4 Signaling system 3.5 Telecommunication system 3.6 Automatic fare collection system Chapter-4 Civil Engineering 4.1 General 4.2 Planning parameters 4.3 Alignment feasibility principles for metro corridors 4.4 -

Handbook-2020-21

The Choice School Nadama East, Tripunithura Kochi – 682301, Kerala Offi ce: 0484 2779057, 2775692, 2780405, 2783912, 2783913, 2783914 Hostel: 0484 2777735 / Fax: 0484 2781951 E-mail: [email protected] Website: www.choiceschool.com The Choice School The Choice School Manthanam P.O, Koolimad - Vellalassery Road. Kunnamthanam, Nairkuzhi P.O Thiruvalla, Kerala 689581 Calicut, Kerala 673601 Ph: 0469 270 0033 Ph: 0495 235 5633 Handbook 2020 -21 This Handbook should be brought to school everyday Discover Experience Accomplish The Power of Education An ISO 9001:2015 Certifi ed Institution VISION Our vision is to provide a happy, caring and stimulating environment where children will recognize and achieve their fullest potential, so that they make their best contribution to the society. MISSION • To develop in the student qualities of integrity, honesty and compassion. • To promote the spirit of enquiry. • To foster scientifi c temper within the bonds of humanism. • To help the students become a meaningful part of their environment. • To see that courage and industry get their just rewards. • To give every child the opportunity to blossom in a non-judgemental and loving environment that guides them in their pursuit of excellence. CORE CONCEPTS *Knowledge *Character *Health THE CHOICE SCHOOL HANDBOOK 2020-21 2 To be fi lled in by the Parent/Guardian PERSONAL RECORD Academic Year : 2020-21 Admission No. : .................................. Name : ........................................................ Date of Birth : ................................. -

Pandemics & Urban Planning

International Journal of Science and Research (IJSR) ISSN: 2319-7064 ResearchGate Impact Factor (2018): 0.28 | SJIF (2019): 7.583 Pandemics & Urban Planning: How a Co-operative Model is Performing Better than a Capitalist Model Anjith Augustine 1Principal Architect & Urban Designer, City+Futures Design Collaborative, Periyar Lane, Thottakkattukara, Aluva, Kerala, India-683509 Abstract: The world is witnessing a catastrophe unfamiliar in recent times. While all the nations are fighting to put breaks on the spread, it is also important to look at different cities healthcare and disaster management models from the perspective of urban planning which is quiet often neglected. Historic references show several examples of city restricting exercises after many mass outbreaks. Different governance models are analyzed based on their recent responses to pandemics and their relationship with urban planning parameters. The paper looks into the importance of urban planning strategies in healthcare especially during critical situations of pandemics and calamities, drawings case studies from different models in the world. Keywords: urban planning, healthy city, pandemic planning 1. Introduction “Historically, epidemics have acted as catalysts in transforming how diseases are handled, especially in urban First time in the recorded history of the world, all the states areas,” said Annie Wilkinson, a research fellow at the have come to a standstill amid Covid-19 outbreak. Cities Institute of Development Studies, a UK-based think tank. which once bustled with people and activities are now silent [2020, Thomas Reuters Foundation] as graveyards. The pandemic is definitely within the purview of the healthcare sector and the immediate remedies are also „Some of the most iconic developments in urban planning being readied. -

Annual Report 2011-12

A N N U A L REPORT 2011 - 2012 ANNUAL REPORT 2011-12 Contents Message from the Chairman 3 Letter from the Managing Director & CEO 5 Board of Directors & Management Team 7 Performance Dashboard 8 Report of the Board of Directors 10 Management Discussion and Analysis 23 Report on Corporate Governance 44 Balance Sheet as at 31 March 2012 58 Profit and Loss Account for the year ended 31 March 2012 59 Schedules 60 Cash Flow Statement 93 Auditors’ Report 94 Basel II - Pillar 3 Disclosures as on 31 March 2012 96 Balance Sheet Abstract and the Bank’s General Business Profile 117 Statement Pursuant to Section 212 of the Companies Act, 1956 118 Related to Subsidiary Companies Accounts of Subsidiary Company Fedbank Financial Services Limited 119 Consolidated Balance Sheet as at 31 March 2012 150 Consolidated Profit and Loss Account for the year ended 31 March 2012 151 Schedules (Consolidated) 152 Consolidated Cash Flow Statement 190 Auditors’ Report (Consolidated) 191 ANNUAL REPORT 2011-12 3 Message from the Chairman I am happy to address you all on the occasion of this 81st However, let me assure you that we need not despair. The Annual General Meeting of your Bank. 2011-12 has been Indian financial markets are more mature, diverse and another excellent year in the history of Federal Bank. I deep. They have resilience to absorb shocks. Our regulatory would like to congratulate the MD & CEO and his able team. systems and crisis response mechanisms are very robust and As you are aware, this performance has been achieved in sophisticated. -

"O(E) Poo)Flco

olo)'l ff)cerco oe(og (r)'lc)offDc oJ(6)l(f)CelCo ODGDp(I)o (I) dru (o d'lorDo'l scor6) 07.02.2019 - 6 o Q olsl €o-. calct3Jo cnaud : 2400 ooosmce go es'Ifl coloer cuJorm) cqD ooc$l8ec6 G-rlCBlo oqoJsl @"1. cesc6na oond6rDc6rB(ru" @1. ES. oJ]. €n(o(occBoa (o5omlcolqo cc$cds"c! o oqolsc(I)&coJCtJo oleql o@1). cttSolcruccor ("4) olJolcruceo) cra,r'flcto 6,"l9loE ("9) "6oemca,go algcoiot : oto'.g[loct€ a,1o1qgg cxJorcrueao.) o0o6rDc@rgo algco),]of, Psaocd, o0GCrots8a,ua Grd@,ocejl, coqor, olcedago SOCO.TgCOC O 6rDCrD" cL$crm)ce0) "{)Or'lO "4cm'loJlseangloE olJ6ro0cdocGoc; ofla,mrcn o6].0'lcoaoJo Grderocel], 6rgocqRol crn1ofl s ocr: gt oE "{) olJolcfDceo ofla,mlcn G.scsa]qo 96ne: (6nn) (enil) slflG2nod ottrotmlccor AJcrBo, crJorm)cao "6cq,r;qogloE : "Ooemc@]go "O(E) c.frcAa,oE po6rBcnoo ole,.Jlao o,lsloE @oldolold6l'm poo)flco GrooJosoeo)Hco cU.xmJco) "Ocgg86,gloel c"-ro'l acoemcnoo crdonos c6cga,oE, ffDoooG66, I ro)"-tcm ean oE cr'fl6m1oeicm gOr-"-lcmrCnCd .'ocrrnol ffi)ofixfflD'lel c croBcocroo of)ooolHcooOr0o oJlc/ooocdoccoc ? Grdoo6rUml)ocaot c d dotoni6rB-. e^102102119 DETAILS of UNITS in DA/DP - ERNAKULAM DISTRICT DP ANGAMALY Name and Address of the Present Sl. No Plot No Name of the unit present Occupant activity/product Fr. Jose Madan, Chief 1 DPA 1 St. Reethas Charitable Trust Cement Bricks Promoter,St.Ritas Charitable Trust A.T.Jose 2 DPA 2 Rajani Industries Arackal House Plastic Sanitary items Angamaly - 688 572 K.K.Jose 3 DPA 3 K.K.Industries Kachapilly House General Engineering Angamaly South Rev. -

Trade Marks Journal No: 1926 , 04/11/2019 Class 37 2851471 28/11/2014 Trading As ;D.M. RATHI and DEVELOPERS MUMBAI

Trade Marks Journal No: 1926 , 04/11/2019 Class 37 2851471 28/11/2014 DHANRAJ MALCHAND RATHI trading as ;D.M. RATHI AND DEVELOPERS S. NO.16/2, SUKHSAGRA NAGAR, NEAR AMBA MATA MANDIR, KATRAJ, PUNE 411046 SERVICE PROVIDER INDIAN NATIONAL Used Since :21/10/1976 MUMBAI BUILDERS AND DEVELOPERS 5128 Trade Marks Journal No: 1926 , 04/11/2019 Class 37 2988848 18/06/2015 S. MANJIT SINGH trading as ;MANJIT PVC JHALOOR ROAD, SHERPUR-148025 (SANGRUR) Service Provider PROPRIETORSHIP FIRM Address for service in India/Agents address: RAHUL RAJPUT. B-336, BHAI RANDHIR SINGH NAGAR, LUDHIANA - 141 004 PUNJAB. Used Since :03/12/2013 DELHI Installation of doors and windows; Installation of PVC fittings on Roof & Walls; Elevator installation and repair; Electric appliance installation and repair; Kitchen equipment installation; Office machines and equipment installation, maintenance and repair 5129 Trade Marks Journal No: 1926 , 04/11/2019 Class 37 3246002 28/04/2016 M/S. SWADESHI CIVIL INFRASTRUCTURE PVT. LTD. trading as ;M/S. SWADESHI CIVIL INFRASTRUCTURE PVT. LTD. 302, DLF, TOWER-B, JASOLA, NEW DELHI-110025 SERVICE PROVIDER Address for service in India/Attorney address: BALAJI IP PRACTICE E-617 STREET NO- 11&12 WEST VINOD NAGAR I.P. EXTN. NEW DELHI-110092 Used Since :25/04/1985 DELHI Building construction; repair; installation services. THE MARK SHALL BE LIMITED TO THE COLOURS AS SHOWN IN THE REPRESENTATION ON THE FORM OF THE APPLICATION. 5130 Trade Marks Journal No: 1926 , 04/11/2019 Class 37 3272724 01/06/2016 SBM INTERNATIONAL PVT. LTD. 5-G, NAAZ BUILDING, LAMINGTON ROAD, MUMBAI- 400 004, MAHARASHTRA, INDIA SERVICE PROVIDERS A CORPORATE ENTITY INCORPORATED IN INDIA UNDER THE COMPANIES ACT,1956 Address for service in India/Attorney address: SAI ANAND SERVICE 73/3, SAI KRUPA CHS., POKHARAN ROAD NO-1, SHIVAI NAGAR, THANE (W)- 400 606, MAHARASHTRA, INDIA. -

VK Ebrahim Kunju

WHO’S WHO V. K. EBRAHIM KUNJU [I.U.M.L.– KALAMASSERY] Son of Shri V. U. Khader and Smt. Chithumma; born at Kongorpilly, Aluva on 20th May 1952; S.S.L.C.; Social Worker. Entered public life through M.S.F. and later became active in Muslim Youth League; Was Secretary/General Secretary (for 25 years), President (for 5 years), Muslim League District Committee, Ernakulam; Chairman, Forest Industries (Travancore) Limited (1993-96); Vice President, Kerala Muslim Educational Association (KMEA); Chairman, C. H. Mohammed Koya College of Engineering and Technology, Edathala; Chaired various organisations and trade unions like Swathanthra Thozhilali Union (S.T.U.) of Eloor Industrial Area, T.E.L.K. Technical Employees Association, Angamaly, Traco Cables Staff and Workers Organisation, Irumpanam, Kerala Minerals and Metals Employees Organisation, Chavara, K.E.L. Employees Union, Mamala, T.C.C. Employees Union, Udyogamandal, Thiruvalla Sugars Union; Director, Cochin International Airport Limited; Syndicate Member, Cochin University of Science and Technology; 84 FOURTEENTH KERALA LEGISLATIVE ASSEMBLY WHO’S WHO Member, Executive Committee, Goshree Islands Development Authority (G.I.D.A.) and Executive Committee, Greater Cochin Development Authority (G.C.D.A.); Secretary, Al Manar Public School; State Vice-President, S.T.U.; President, Officers Forum of T.C.C., Traco Employees Organisation, Thiruvalla; General Secretary, Binani Zinc Workers Federation, G.T.N. Workers Association; Member, District Board of the Kerala Grandhasala Sanghom, Ernakulam District Development Council. Was Minister for Industries and Social Welfare (6-1-2005 to 12-5-2006); Minister for Public Works (23-5-2011 to 20-5-2016). Now member, Kerala State Muslim League Secretariat; Chairman, Committee on Government Assurances. -

District:HEAD OFFICE, THIRUVANANTHAPURAM

District:HEAD OFFICE, THIRUVANANTHAPURAM ICE/ ICO/ Category Date of Date of ICO(R) / Name and & Capital Fee DD No & Date of Issue of No. Validity Application Registrtn/ Address Type of investment remitted Date enquiry clearance/ Authoristn/ industry Refusal Refusal Instrumentation 1 online CVO red 22.63 Cr 3 lakhs 03.11.2015 29.02.2016 30.06.2018 ltd Palakkad Muraliya 2 online CVO red 35 Cr 1 lakhs 21.07.2014 29.02.2016 31.05.2017s Products TVM Baby Memorial 3 online ICO-R red 94 Cr 360000 28.07.2015 17.02.2016 30.06.2018 hospital Ltd. KKD Mahindra Holidays & 4 online ICO-R Orange 23.87 Cr 180000 13.01.2016 02.03.2016 31.01.2019 Resorts India Ltd, Kollam Anjali Crusher 5 online ICO red 1-5 Cr 1.3 lakh 25.06.2015 08.02.2016 30.06.2018 Industries, TVM M/s.MARIA THERESA HOSPITAL, 6 online ICO-R RED 74,24,564/- 60000/- 07.12.2015 28.02.2016 30.06.2018 KUZHIKKATTSSE RY,THRISUR- 680697 M/s.PETRONET LNG LTD, 4502.75 11,056,60 7 online ICO-R PUTHUVYPPU ORANGE 09.02.2015 28.02.2016 31.03.2018 P.O.,ERNAKULAM- CRORES 0/- 682508 Assisi 8 online ICO-R Atonemment red 2.44 cr 70,000/- 19.12.2015 29.02.2016 28.02.2018 Hospital-Kollam Vivanta By Taj 9 online ICO-R Orange 93.2 cr 300000/- 19.01.2016 01.03.2016 28.02.2019 (Doodla) TVM Tamara Real 10 online CVO Estate Holdings Orange 8800 lakhs 1.6 lakhs 29.03.2014 01.03.2016 31.01.2017 and developers Kannamthanam 11 online ICO-R red 10 cr 210000 22.01.2016 29.02.2016 28.02.2019 & Co, TVM Travancore Blue 12 online ICO-R red 5.89 cr 210000 03.02.2016 02.03.2016 28.02.2019 metals-TVM OFFICE : RO - Thiruvananthapuram ICE/ ICO/ Date of Date of ICO(R) / Category & Capital Fee Issue of No.