A Seven-Planet Resonant Chain in TRAPPIST-1 Rodrigo Luger, Marko Sestovic, Ethan Kruse, Simon L

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Planetary Phase Variations of the 55 Cancri System

The Astrophysical Journal, 740:61 (7pp), 2011 October 20 doi:10.1088/0004-637X/740/2/61 C 2011. The American Astronomical Society. All rights reserved. Printed in the U.S.A. PLANETARY PHASE VARIATIONS OF THE 55 CANCRI SYSTEM Stephen R. Kane1, Dawn M. Gelino1, David R. Ciardi1, Diana Dragomir1,2, and Kaspar von Braun1 1 NASA Exoplanet Science Institute, Caltech, MS 100-22, 770 South Wilson Avenue, Pasadena, CA 91125, USA; [email protected] 2 Department of Physics & Astronomy, University of British Columbia, Vancouver, BC V6T1Z1, Canada Received 2011 May 6; accepted 2011 July 21; published 2011 September 29 ABSTRACT Characterization of the composition, surface properties, and atmospheric conditions of exoplanets is a rapidly progressing field as the data to study such aspects become more accessible. Bright targets, such as the multi-planet 55 Cancri system, allow an opportunity to achieve high signal-to-noise for the detection of photometric phase variations to constrain the planetary albedos. The recent discovery that innermost planet, 55 Cancri e, transits the host star introduces new prospects for studying this system. Here we calculate photometric phase curves at optical wavelengths for the system with varying assumptions for the surface and atmospheric properties of 55 Cancri e. We show that the large differences in geometric albedo allows one to distinguish between various surface models, that the scattering phase function cannot be constrained with foreseeable data, and that planet b will contribute significantly to the phase variation, depending upon the surface of planet e. We discuss detection limits and how these models may be used with future instrumentation to further characterize these planets and distinguish between various assumptions regarding surface conditions. -

Interior Dynamics of Super-Earth 55 Cancri E Constrained by General Circulation Models

Geophysical Research Abstracts Vol. 21, EGU2019-4167, 2019 EGU General Assembly 2019 © Author(s) 2019. CC Attribution 4.0 license. Interior dynamics of super-Earth 55 Cancri e constrained by general circulation models Tobias Meier (1), Dan J. Bower (1), Tim Lichtenberg (2), and Mark Hammond (2) (1) Center for Space and Habitability, Universität Bern , Bern, Switzerland , (2) Department of Physics, University of Oxford, Oxford, United Kingdom Close-in and tidally-locked super-Earths feature a day-side that always faces the host star and are thus subject to intense insolation. The thermal phase curve of 55 Cancri e, one of the best studied super-Earths, reveals a hotspot shift (offset of the maximum temperature from the substellar point) and a large day-night temperature contrast. Recent general circulation models (GCMs) aiming to explain these observations determine the spatial variability of the surface temperature of 55 Cnc e for different atmospheric masses and compositions. Here, we use constraints from the GCMs to infer the planet’s interior dynamics using a numerical geodynamic model of mantle flow. The geodynamic model is devised to be relatively simple due to uncertainties in the interior composition and structure of 55 Cnc e (and super-Earths in general), which preclude a detailed treatment of thermophysical parameters or rheology. We focus on several end-member models inspired by the GCM results to map the variety of interior regimes relevant to understand the present-state and evolution of 55 Cnc e. In particular, we investigate differences in heat transport and convective style between the day- and night-sides, and find that the thermal structure close to the surface and core-mantle boundary exhibits the largest deviations. -

Exoplanet Community Report

JPL Publication 09‐3 Exoplanet Community Report Edited by: P. R. Lawson, W. A. Traub and S. C. Unwin National Aeronautics and Space Administration Jet Propulsion Laboratory California Institute of Technology Pasadena, California March 2009 The work described in this publication was performed at a number of organizations, including the Jet Propulsion Laboratory, California Institute of Technology, under a contract with the National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA). Publication was provided by the Jet Propulsion Laboratory. Compiling and publication support was provided by the Jet Propulsion Laboratory, California Institute of Technology under a contract with NASA. Reference herein to any specific commercial product, process, or service by trade name, trademark, manufacturer, or otherwise, does not constitute or imply its endorsement by the United States Government, or the Jet Propulsion Laboratory, California Institute of Technology. © 2009. All rights reserved. The exoplanet community’s top priority is that a line of probeclass missions for exoplanets be established, leading to a flagship mission at the earliest opportunity. iii Contents 1 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY.................................................................................................................. 1 1.1 INTRODUCTION...............................................................................................................................................1 1.2 EXOPLANET FORUM 2008: THE PROCESS OF CONSENSUS BEGINS.....................................................2 -

Recipe for a Habitable Planet

Recipe for a Habitable Planet Aomawa Shields Clare Boothe Luce Associate Professor Shields Center for Exoplanet Climate and Interdisciplinary Education (SCECIE) University of California, Irvine ASU School of Earth and Space Exploration (SESE) December 2, 2020 A moment to pause… Leading effectively during COVID-19 • Employees Need Trust and Compassion: Be Present, Even When You're Distant • Employees Need Stability: Prioritize Wellbeing Amid Disruption • Employees Need Hope: Anchor to Your "True North" From “3 strategies for leading effectively during COVID-19” (https://www.gallup.com/workplace/306503/strategies-leading-effectively-amid-covid.aspx) Hobbies: reading movies, shows knitting mixed media/collage violin tea yoga good restaurants spa days the beach hiking smelling flowers hanging with family BINGO Ill. Niklas Elmehed. Ill. Niklas Elmehed. © Nobel Media. © Nobel Media. RadialVelocity (m/s) Nobel Prize in Physics 2019 Mayor & Queloz 1995 https://exoplanets.nasa.gov/ As of December 2, 2020 Aomawa Shields Recipe for a Habitable World Credit: NASA NNASA’sASA’s KKeplerepler MMissionission TESS Transiting Exoplanet Survey Satellite Credit: NASA-JPL/Caltech Proxima Centauri b Credit: ESO/M. Kornmesser LHS 1140b Credit: ESO TOI 700d Credit: NASA TESS planets in the Earth-sized regime Credit: NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center Which ones do we follow up on? 20 The Habitable Zone (Kasting et al. 1993, Kopparapu et al. 2013) ) Runaway greenhouse Maximum CO2 greenhouse Stellar Mass (M Mass Stellar Distance from Star (AU) Snowball Earth Many factors can affect planetary habitability Aomawa Shields Recipe for a Habitable World Liquid water Aomawa Shields Recipe for a Habitable World Isotopic Birth Tides Orbit Abundance Environ. -

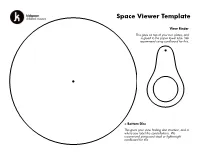

Space Viewer Template

Space Viewer Template View Finder This goes on top of your two plates, and is glued to the paper towel tube. We recommend using cardboard for this. < Bottom Disc This gives your view finding disc structure, and is where you label the constellations. We recommend using card stock or lightweight cardboard for this. Constellation Plate > This disc is home to your constellations, and gets glued to the larger disc. We recommend using paper for this, so the holes are easier to punch. Use the punch guides on the next page to punch holes and add labels to your viewer. Orion Cancer Look for the middle star of Orions When you look at this constellation, look sword, that is an area of brighter nearby for 55 Cancri a star that has light, it’s actually a nebula! The five exoplanets orbiting it. One of those Orion Nebula is a gigantic cloud of plants (55 Cancri e) is a super hot dust and gas, where new stars are planet entirely covered in an ocean of being created. lava! Cygnus Andromeda This constellation is home to the This constellation is very close to the Kepler-186 system, including the Andromeda Galaxy (an enormous planet Kepler-186f. Seen by collection of gas, dust, and billions of NASA's Kepler Space Telescope, stars and solar systems). This spiral this is the first Earth-sized planet galaxy is so bright, you can spot it with discovered that is in"habitable the naked eye! zone" of its star. Ursa Minor Cassiopeia Ursa Minor has two stars known While gazing at Cassiopeia look for with exoplanets orbiting them - the“Pacman Nebula” (It’s official name both are gas giants, that are much is NGC 281). -

A Case for an Atmosphere on Super-Earth 55 Cancri E

The Astronomical Journal, 154:232 (8pp), 2017 December https://doi.org/10.3847/1538-3881/aa9278 © 2017. The American Astronomical Society. All rights reserved. A Case for an Atmosphere on Super-Earth 55 Cancri e Isabel Angelo1,2 and Renyu Hu1,3 1 Jet Propulsion Laboratory, California Institute of Technology, 4800 Oak Grove Drive, Pasadena, CA 91109, USA; [email protected] 2 Department of Astronomy, University of California, Campbell Hall, #501, Berkeley CA, 94720, USA 3 Division of Geological and Planetary Sciences, California Institute of Technology, Pasadena, CA 91125, USA Received 2017 August 2; revised 2017 October 6; accepted 2017 October 8; published 2017 November 16 Abstract One of the primary questions when characterizing Earth-sized and super-Earth-sized exoplanets is whether they have a substantial atmosphere like Earth and Venus or a bare-rock surface like Mercury. Phase curves of the planets in thermal emission provide clues to this question, because a substantial atmosphere would transport heat more efficiently than a bare-rock surface. Analyzing phase-curve photometric data around secondary eclipses has previously been used to study energy transport in the atmospheres of hot Jupiters. Here we use phase curve, Spitzer time-series photometry to study the thermal emission properties of the super-Earth exoplanet 55 Cancri e. We utilize a semianalytical framework to fit a physical model to the infrared photometric data at 4.5 μm. The model uses parameters of planetary properties including Bond albedo, heat redistribution efficiency (i.e., ratio between radiative timescale and advective timescale of the atmosphere), and the atmospheric greenhouse factor. -

![Arxiv:2010.01074V2 [Astro-Ph.EP] 14 Jan 2021 Four Years](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/6353/arxiv-2010-01074v2-astro-ph-ep-14-jan-2021-four-years-1366353.webp)

Arxiv:2010.01074V2 [Astro-Ph.EP] 14 Jan 2021 Four Years

Draft version January 18, 2021 Typeset using LATEX twocolumn style in AASTeX63 Refining the transit timing and photometric analysis of TRAPPIST-1: Masses, radii, densities, dynamics, and ephemerides. Eric Agol ,1 Caroline Dorn ,2 Simon L. Grimm ,3 Martin Turbet ,4 Elsa Ducrot ,5 Laetitia Delrez ,6, 4, 5 Michaël Gillon ,5 Brice-Olivier Demory ,3 Artem Burdanov ,7 Khalid Barkaoui ,8, 5 Zouhair Benkhaldoun ,8 Emeline Bolmont ,4 Adam Burgasser ,9 Sean Carey ,10 Julien de Wit ,7 Daniel Fabrycky ,11 Daniel Foreman-Mackey ,12 Jonas Haldemann ,13 David M. Hernandez ,14 James Ingalls ,10 Emmanuel Jehin ,6 Zachary Langford ,1 Jérémy Leconte ,15 Susan M. Lederer ,16 Rodrigo Luger ,12 Renu Malhotra ,17 Victoria S. Meadows ,1 Brett M. Morris ,3 Francisco J. Pozuelos ,6, 5 Didier Queloz ,18 Sean N. Raymond ,15 Franck Selsis ,15 Marko Sestovic ,3 Amaury H.M.J. Triaud ,19 and Valerie Van Grootel 6 1Astronomy Department and Virtual Planetary Laboratory, University of Washington, Seattle, WA 98195 USA 2University of Zurich, Institute of Computational Sciences, Winterthurerstrasse 190, CH-8057, Zurich, Switzerland 3Center for Space and Habitability, University of Bern, Gesellschaftsstrasse 6, CH-3012, Bern, Switzerland 4Observatoire de Genève, Université de Genève, 51 Chemin des Maillettes, CH-1290 Sauverny, Switzerland 5Astrobiology Research Unit, Université de Liège, Allée du 6 Août 19C, B-4000 Liège, Belgium 6Space Sciences, Technologies and Astrophysics Research (STAR) Institute, Université de Liège, Allée du 6 Août 19C, B-4000 Liège, Belgium 7Department -

Abstracts of Extreme Solar Systems 4 (Reykjavik, Iceland)

Abstracts of Extreme Solar Systems 4 (Reykjavik, Iceland) American Astronomical Society August, 2019 100 — New Discoveries scope (JWST), as well as other large ground-based and space-based telescopes coming online in the next 100.01 — Review of TESS’s First Year Survey and two decades. Future Plans The status of the TESS mission as it completes its first year of survey operations in July 2019 will bere- George Ricker1 viewed. The opportunities enabled by TESS’s unique 1 Kavli Institute, MIT (Cambridge, Massachusetts, United States) lunar-resonant orbit for an extended mission lasting more than a decade will also be presented. Successfully launched in April 2018, NASA’s Tran- siting Exoplanet Survey Satellite (TESS) is well on its way to discovering thousands of exoplanets in orbit 100.02 — The Gemini Planet Imager Exoplanet Sur- around the brightest stars in the sky. During its ini- vey: Giant Planet and Brown Dwarf Demographics tial two-year survey mission, TESS will monitor more from 10-100 AU than 200,000 bright stars in the solar neighborhood at Eric Nielsen1; Robert De Rosa1; Bruce Macintosh1; a two minute cadence for drops in brightness caused Jason Wang2; Jean-Baptiste Ruffio1; Eugene Chiang3; by planetary transits. This first-ever spaceborne all- Mark Marley4; Didier Saumon5; Dmitry Savransky6; sky transit survey is identifying planets ranging in Daniel Fabrycky7; Quinn Konopacky8; Jennifer size from Earth-sized to gas giants, orbiting a wide Patience9; Vanessa Bailey10 variety of host stars, from cool M dwarfs to hot O/B 1 KIPAC, Stanford University (Stanford, California, United States) giants. 2 Jet Propulsion Laboratory, California Institute of Technology TESS stars are typically 30–100 times brighter than (Pasadena, California, United States) those surveyed by the Kepler satellite; thus, TESS 3 Astronomy, California Institute of Technology (Pasadena, Califor- planets are proving far easier to characterize with nia, United States) follow-up observations than those from prior mis- 4 Astronomy, U.C. -

Near-Resonance in a System of Sub-Neptunes from TESS

Near-resonance in a System of Sub-Neptunes from TESS The MIT Faculty has made this article openly available. Please share how this access benefits you. Your story matters. Citation Quinn, Samuel N., et al.,"Near-resonance in a System of Sub- Neptunes from TESS." Astronomical Journal 158, 5 (November 2019): no. 177 doi 10.3847/1538-3881/AB3F2B ©2019 Author(s) As Published 10.3847/1538-3881/AB3F2B Publisher American Astronomical Society Version Final published version Citable link https://hdl.handle.net/1721.1/124708 Terms of Use Article is made available in accordance with the publisher's policy and may be subject to US copyright law. Please refer to the publisher's site for terms of use. The Astronomical Journal, 158:177 (16pp), 2019 November https://doi.org/10.3847/1538-3881/ab3f2b © 2019. The American Astronomical Society. All rights reserved. Near-resonance in a System of Sub-Neptunes from TESS Samuel N. Quinn1 , Juliette C. Becker2 , Joseph E. Rodriguez1 , Sam Hadden1 , Chelsea X. Huang3,45 , Timothy D. Morton4 ,FredC.Adams2 , David Armstrong5,6 ,JasonD.Eastman1 , Jonathan Horner7 ,StephenR.Kane8 , Jack J. Lissauer9, Joseph D. Twicken10 , Andrew Vanderburg11,46 , Rob Wittenmyer7 ,GeorgeR.Ricker3, Roland K. Vanderspek3 , David W. Latham1 , Sara Seager3,12,13,JoshuaN.Winn14 , Jon M. Jenkins9 ,EricAgol15 , Khalid Barkaoui16,17, Charles A. Beichman18, François Bouchy19,L.G.Bouma14 , Artem Burdanov20, Jennifer Campbell47, Roberto Carlino21, Scott M. Cartwright22, David Charbonneau1 , Jessie L. Christiansen18 , David Ciardi18, Karen A. Collins1 , Kevin I. Collins23,DennisM.Conti24,IanJ.M.Crossfield3, Tansu Daylan3,48 , Jason Dittmann3 , John Doty25, Diana Dragomir3,49 , Elsa Ducrot17, Michael Gillon17 , Ana Glidden3,12 , Robert F. -

How to Detect Exoplanets Exoplanets: an Exoplanet Or Extrasolar Planet Is a Planet Outside the Solar System

Exoplanets Matthew Sparks, Sobya Shaikh, Joseph Bayley, Nafiseh Essmaeilzadeh How to detect exoplanets Exoplanets: An exoplanet or extrasolar planet is a planet outside the Solar System. Transit Method: When a planet crosses in front of its star as viewed by an observer, the event is called a transit. Transits by terrestrial planets produce a small change in a star's brightness of about 1/10,000 (100 parts per million, ppm), lasting for 2 to 16 hours. This change must be absolutely periodic if it is caused by a planet. In addition, all transits produced by the same planet must be of the same change in brightness and last the same amount of time, thus providing a highly repeatable signal and robust detection method. Astrometry: Astrometry is the area of study that focuses on precise measurements of the positions and movements of stars and other celestial bodies, as well as explaining these movements. In this method, the gravitational pull of a planet causes a star to change its orbit over time. Careful analysis of the changes in a star's orbit can provide an indication that there exists a massive exoplanet in orbit around the star. The astrometry technique has benefits over other exoplanet search techniques because it can locate planets that orbit far out from the star Radial Velocity method: The radial velocity method to detect exoplanet is based on the detection of variations in the velocity of the central star, due to the changing direction of the gravitational pull from an (unseen) exoplanet as it orbits the star. -

Mathematics 3–4

Mathematics 3{4 Mathematics Department Phillips Exeter Academy Exeter, NH July 2020 To the Student Contents: Members of the PEA Mathematics Department have written the material in this book. As you work through it, you will discover that algebra, geometry, and trigonometry have been integrated into a mathematical whole. There is no Chapter 5, nor is there a section on tangents to circles. The curriculum is problem-centered, rather than topic-centered. Techniques and theorems will become apparent as you work through the problems, and you will need to keep appropriate notes for your records | there are no boxes containing important theorems. There is no index as such, but the reference section that starts on page 101 should help you recall the meanings of key words that are defined in the problems (where they usually appear italicized). Problem solving: Approach each problem as an exploration. Reading each question care- fully is essential, especially since definitions, highlighted in italics, are routinely inserted into the problem texts. It is important to make accurate diagrams. Here are a few useful strategies to keep in mind: create an easier problem, use the guess-and-check technique as a starting point, work backwards, recall work on a similar problem. It is important that you work on each problem when assigned, since the questions you may have about a problem will likely motivate class discussion the next day. Problem solving requires persistence as much as it requires ingenuity. When you get stuck, or solve a problem incorrectly, back up and start over. Keep in mind that you're probably not the only one who is stuck, and that may even include your teacher. -

Secure TTV Mass Measurements: Ten Kepler Exoplanets Between 3 and 8 M⊕ with Diverse Densities and Incident Fluxes” (2016, Apj, 820, 39)

The Astrophysical Journal, 849:73 (2pp), 2017 November 1 https://doi.org/10.3847/1538-4357/aa8d19 © 2017. The American Astronomical Society. All rights reserved. Erratum: “Secure TTV Mass Measurements: Ten Kepler Exoplanets between 3 and 8 M⊕ with Diverse Densities and Incident Fluxes” (2016, ApJ, 820, 39) Daniel Jontof-Hutter1,2 , Eric B. Ford2 , Jason F. Rowe3 , Jack J. Lissauer4, Daniel C. Fabrycky5, Christa Van Laerhoven6, Eric Agol7 , Katherine M. Deck8, Tomer Holczer9 , and Tsevi Mazeh9 1 Department of Physics, University of the Pacific, Stockton, CA 95211, USA; djontofhutter@pacific.edu 2 Department of Astronomy and Astrophysics, 525 Davey Laboratory, Pennsylvania State University, University Park, PA 16802, USA 3 Department of Physics and Astronomy, Bishop’s University, Sherbrooke, Quebec J1M IZ7, Canada 4 Space Science and Astrobiology Division, MS 245-3, NASA Ames Research Center, Moffett Field, CA 94035, USA 5 Department of Astronomy and Astrophysics, University of Chicago, 5640 South Ellis Avenue, Chicago, IL 60637, USA 6 Canadian Institute for Theoretical Astrophysics, 60 St. George Street, Toronto, ON M5S 3H8, Canada 7 Department of Astronomy, University of Washington, Seattle, WA 98195, USA 8 Division of Geological and Planetary Sciences, California Institute of Technology, Pasadena, CA, USA 9 School of Physics and Astronomy, Raymond and Beverly Sackler Faculty of Exact Sciences, Tel Aviv University, Tel Aviv 69978, Israel Received 2017 August 31; accepted 2017 September 12; published 2017 November 2 Some of the figures in the original manuscript showing the joint posteriors of esinw of neighboring planets are incorrect. The original figures erroneously displayed joint posteriors of ecosw. The originals and their corrections are plotted below.