Bebop -Ross Russell

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Charlie Parker: Two New Bios and a Revision Crouch, Haddix and Giddins

Journal of Jazz Studies vol. 10, no. 1, pp. 72-77 (Summer 2014) Charlie Parker: Two New Bios And A Revision Crouch, Haddix and Giddins Jeff Sultanof Kansas City Lightning: The Rise and Times of Charlie Parker. By Stanley Crouch. New York: NY: HarperCollins Publishers. 384 pp. Bird: The Life and Music of Charlie Parker. By Chuck Haddix. Urbana: University of Illinois Press. 224 pp. Celebrating Bird: The Triumph of Charlie Parker (Revised Edition). By Gary Giddins. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press. 208 pp. “We were playing white dances, and during intermission you couldn’t go out into the audience, so you stayed backstage. I was sitting at the piano, fooling around with something. Some white guy said, 'Hey …' to me and thumped a nickel on the stand. And then he said, 'When you come back on, play so-and-so' ... I looked down at the nickel and up at this dude, and picked up the nickel and threw it someplace, and just kept playing. Later on that night, after the dance was over, I thought everyone had left and we could go to the 'white' men’s room. While they were dancing, all the men’s rooms were white, and the women’s too. Anyway, I went in and came out of the men’s room, and as I was coming out I saw this shadow behind my head coming down. This bottle was coming at my head. So I just happened to turn, just a little bit, and the guy caught me in the back of the head with this bottle. -

Yardbird in Lotus Land

s most collectors know adequate documenta- and were made shortly after the band had been ion of the changes that took place in American formed, before much opportunity had been zz during the early 1940s will never be pos- allowed for rehearsals. The, band's pianist at ible because of the AFIVI recording ban which this time was Joe Albany, later to be replaced ook place from 1942 to 1945. As a result the by Dodo Marmarosa, and his performances here pact and development of such, key figures as are important additions to his solography. They harlie Parker, Dizzy Gillespie, Fats Navarro, also plug a sizeable hole in the development of helonious Monk and Bud Powell has to be young Miles Davis' early career as well as offer- :ken, in many cases as hearsay. For recorded ing yet more previously unissued Charlie Parker xamples of their musical development the jazz performances with a band that never made it to udent must rely on bits and pieces — short the studio. los by Monk and Powell in swing groups and r early Charlie Parker, the radio transcriptions Liner Notes: ROSS RUSSELL (Jan. 1975, e made with Jay McShann for a radio station author Bird Lives) Wichita, Kansas (available on Spotlite Production: TONY WILLIAMS PJ120). Thanks to the efforts of researchers, Sleeve Design: MALCOLM WALKER ollectors and the specialist record labels some f these gaps are gradually being filled. For further information for the period during which these recordings were made Spotlite yen 'after the recording ban recording dates recommend that the chapter "Yardbird in Lotus ere often few and far between for many musi- Land" be read from Ross Russell's excellent ians involved in the new form of musical Biography on Charlie Parker "Bird Lives" xpression. -

Primary Sources: an Examination of Ira Gitler's

PRIMARY SOURCES: AN EXAMINATION OF IRA GITLER’S SWING TO BOP AND ORAL HISTORY’S ROLE IN THE STORY OF BEBOP By CHRISTOPHER DENNISON A thesis submitted to the Graduate School-Newark Rutgers University, The State University of New Jersey In partial fulfillment of the requirements of Master of Arts M.A. Program in Jazz History and Research Written under the direction of Dr. Lewis Porter And approved by ___________________________ _____________________________ Newark, New Jersey May, 2015 ABSTRACT OF THE THESIS Primary Sources: An Examination of Ira Gitler’s Swing to Bop and Oral History’s Role in the Story of Bebop By CHRISTOPHER DENNISON Thesis director: Dr. Lewis Porter This study is a close reading of the influential Swing to Bop: An Oral History of the Transition of Jazz in the 1940s by Ira Gitler. The first section addresses the large role oral history plays in the dominant bebop narrative, the reasons the history of bebop has been constructed this way, and the issues that arise from allowing oral history to play such a large role in writing bebop’s history. The following chapters address specific instances from Gitler’s oral history and from the relevant recordings from this transitionary period of jazz, with musical transcription and analysis that elucidate the often vague words of the significant musicians. The aim of this study is to illustratethe smoothness of the transition from swing to bebop and to encourage a sense of skepticism in jazz historians’ consumption of oral history. ii Acknowledgments The biggest thanks go to Dr. Lewis Porter and Dr. -

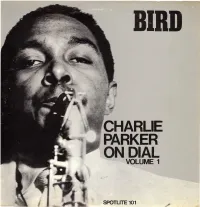

Charlie Parker on Dial Volume 1

The Charlie Parker/Dial association started in The session ran from 1 p.m.-6 p.m. and the intro and gave the cue for Charlie's entrance, January 1946 while Dizzy Gillespie and Bird were was notable—so Ross Russell recalls—for being the but nothing happened. He stood in front of the playing an engagement at Billy Berg's club with the only occasion on which Bird was on time. In fact microphone but no notes came from his horn until sextet they had brought over to the coast he was there early, bustling about, all busyness, well into the second bar. His solo is one of strange comprising Bird, Dizzy, Milt Jackson, Al Haig, Ray very much enjoying his new role as leader and beauty full of gasping pauses and heartbreak Brown and Stan Levey. The group never recorded musical director. In order not repeat previous phrases. During his solo he kept swaying and once as such and only two broadcasts are known to mistakes the session was kept a secret. 3 takes of spun completely around so that he went badly "off exist, namely DIZZY ATMOSPHERE (issued on MOOSE THE MOOCHE, named after Emry Byrd, mike" as can be heard on the record. Charlie then Klacto MG102) and SALT PEANUTS. The first 4 takes each of YARDBIRD SUITE anc decided to try THE GYPSY a number he had been CHARLIE recording session for the newly-launched Dial label ORNITHOLOGY and 5 takes of NIGHT IN playing a lot at the Hi De Ho. This time he came in was scheduled to take place on Tuesday, January TUNISIA were recorded. -

LAJI/Bebop Brochure Final

Presents GROOVIN’ HIGH A Celebration of the BeBop Era MAY 24 - 27, 2001 Box 8038 The Crowne Plaza O. P. THE LOS ANGELES JAZZ INSTITUTETHE LOS ANGELES JAZZ Long Beach, CA 90808-0038 Redondo Beach & Marina Hotel GROOVIN’ HIGH The Los Angeles Jazz Institute is pleased to announce CONVENTION FACTS Groovin’ High-An All-Star Celebration of the Bebop Era taking place May 24-27, 2001 at The Crowne Plaza Hotel DATES in Redondo Beach, California. May 24-27, 2001 Groovin’ High promises to be one of the most outstanding jazz gatherings to ever take place in southern California. We are fortunate in being able to bring together most of the living giants PLACE of the bop era. The primary period that we are focusing on is The Crowne Plaza 1945-1950. This was one of the most important periods in the Redondo Beach & history of jazz due to the brilliant musical revolutions that exploded Marina Hotel during those five years. A number of concerts have been designed 300 North Harbor Drive featuring musicians who were part of the bebop revolution as well Redondo Beach, California as several repertory concerts performing important music from the 90277 era. There will also be film showings and panel discussions where the story of modern jazz will be told by the artists who created it. The special convention rate Full Registration is $300 if you order by April 15. is $134 per night. After that date, the full registration price will be $350. Hotel stay not included Full registrants will have reserved seating for all concerts. -

Four Studies of Charlie Parker's Compositional Processes

Four Studies of Charlie Parker’s Compositional Processes Henry Martin NOTE: The examples for the (text-only) PDF version of this item are available online at: hp://www.mtosmt.org/issues/mto.18.24.2/mto.18.24.2.martin.php KEYWORDS: Charlie Parker, jazz, jazz composition, bebop, jazz analysis, “Ornithology,” “Blues (Fast),” “Red Cross,” “My Lile Suede Shoes” ABSTRACT: Charlie Parker has been much appreciated as an improviser, but he was also an important jazz composer, a topic yet to be studied in depth. Parker’s compositions offer insight into his total musicianship as well as provide a summary of early bebop style. Because he left no working manuscripts, we cannot examine his compositions evolving on paper. We do possess occasional single parts for trumpet or alto saxophone of pieces wrien for recording sessions and four Library of Congress lead sheets copied in his hand, and, as an introduction, I show examples of such manuscripts. The article continues by exploring what we can infer about Parker’s compositional processes from those instances where he made revisions to improve or create the final product. In particular, there is one instance of Parker revising a work already completed (“Ornithology”), one instance of Parker combining two pieces by another composer into one of his own (“My Lile Suede Shoes”), and two instances of Parker composing in the studio where we can hear his revisions immediately (“Red Cross” and “Blues (Fast)”). The middle part of the paper explores Parker in these creative seings. Parker’s methods sometimes differ from traditional composition and suggest that we reconsider the usual distinction between improvisation and composition. -

Fats" Navarro, 1949-1950 Russell C

University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln Student Research, Creative Activity, and Music, School of Performance - School of Music Spring 4-20-2016 A Study of the Improvisational Style of Theodore "Fats" Navarro, 1949-1950 Russell C. Zimmer University of Nebraska - Lincoln, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.unl.edu/musicstudent Part of the Music Pedagogy Commons, Music Performance Commons, Music Theory Commons, and the Other Music Commons Zimmer, Russell C., "A Study of the Improvisational Style of Theodore "Fats" Navarro, 1949-1950" (2016). Student Research, Creative Activity, and Performance - School of Music. 98. http://digitalcommons.unl.edu/musicstudent/98 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Music, School of at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in Student Research, Creative Activity, and Performance - School of Music by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. A Study of the Improvisational Style of Theodore “Fats” Navarro 1949-1950 by Russell Zimmer A Doctoral Document Presented to the Faculty of The Graduate College at the University of Nebraska In Partial Fulfillment of Requirements For the Degree of Doctor of Musical Arts Major: Music Under the Supervision of Professor Darryl White Lincoln, Nebraska April, 2016 A Study of the Improvisational Style of Theodore “Fats” Navarro 1949-1950 Russell Zimmer, D.M.A. University of Nebraska, 2016 Adviser: Darryl White This study analyzes improvisatory techniques of Theodore “Fats” Navarro (1923- 1950). Live improvised solos of the trumpeter from 1949-1950 were examined to better understand the improvisational style through the analysis of transcribed solos. -

Mosaic Discography (PDF)

THE COMPLETE DIAL MODERN JAZZ SESSIONS Mosaic MD9-260 Disc I: 1. Hallelujah (tk.A) (A) 4:08 (Youmans-Robbins-Grey) 2. Hallelujah (tk.B) (A) 4:09 (Youmans-Robbins-Grey) 3. Hallelujah (tk.F) (A) 3:42 (Youmans-Robbins-Grey) 4. Get Happy (tk B) (A) 4:00 (H. Arlen-T. Koehler) 5. Get Happy (tk D) (A) 3:42 (H. Arlen-T. Koehler) 6. Slim Slam Blues (tk.A) (A) 5:02 (Red Norvo) 7. Slim Slam Blues (tk.B) (A) 4:25 (Red Norvo) 8. Congo Blues (false start 1) (A) 1:04 (Red Norvo) 9. Congo Blues (false start 2) (A) 1:14 (Red Norvo) 10. Congo Blues (tk A) (A) 3:59 (Red Norvo) 11. Congo Blues (tk B) (A) 3:51 (Red Norvo) 12. Congo Blues (tk.C) (A) 3:51 (Red Norvo) 13. Play Piano, Play (L) 3:17 (Erroll Garner) 14. Love Is The Strangest Game (tk.A) (L) 3:19 (Erroll Garner) 15. Love Is The Strangest Game (tk.B) (L) 2:49 (Erroll Garner) 16. Blues Garni (L) 2:42 (Erroll Garner) 17. Don’t Worry ‘Bout Me (tk.A) (L) 3:45 (T. Koehler-R. Bloom) 18. Don’t Worry ‘Bout Me (tk.B) (L) 3:03 (T. Koehler-R. Bloom) 19. Don’t Worry ‘Bout Me (tk C) (L) 3:15 (T. Koehler-R. Bloom) 20. Loose Nut (L) 2:59 (Erroll Garner) 21. Love For Sale (L) 2:48 (Cole Porter) 22. Fantasy On Frankie And Johnny (L) 2:58 (traditional) 23. Sloe Gin Fizz (L) 2:47 (Erroll Garner) Disc II: 1. -

JREV3.9FULL.Pdf

VOLUME 3, NUMBER 9, NOVEMBER, 1960 Editors: Nat Hentoff Martin Williams 4 Budd Johnson, an Ageless Jazzman Contributing Editor: Gunther Schuller Frank Driggs Publisher: Hsio Wen Shih Art Director: Bob Cato Ul 8 Charlie Parker, a Biography in Interviews The Jazz Review is published monthly Bob Reisner by The Jazz Review Inc., 124 White St., N. Y. 13 N. Y. Entire contents copy• right 1960 by The Jazz Review Inc. 12 Earl Hines on Charlie Parker Israel Young and Leonard Feldman were among the founders of the Jazz Review. Dick Hadlock Price per copy 50c. One year's subscription $5.00. Two year's subscription $9.00. Unsolicited manuscripts and illustrations 14 Two Reports on The School of Jazz should be accompanied by a stamped, self- addressed envelope. Reasonable care will be Gunther Schuller and Don Heckman taken with all manuscripts and illustrations, but the Jazz Review can take no responsi• bility for unsolicited material. 20 The Blues RECORD REVIEWS 21 Dizzy Gillespie-Charlie Parker by Ross Russell 23 Ornette Coleman by Martin Williams 24 Ornette Coleman by Hsio Wen Shih 26 Miles Davis by Harvey Pekar 27 Buddy deFranco by Harvey Pekar Kenny Dorham by Zita Carno Harry Edison by Louis Levy 28 Barry Harris by Martin Williams Stan Kenton by Don Heckman 29 George Russell by Max Harrison 31 Mai Waldron by John William Hardy 32 Dinah Washington by Ross Russell Jimmy Rodgers and Ray Charles by Mimi Clar 33 Shorter Reviews by Henry Woodfin 34 Jazz In Print by Nat Hentoff I 36 The Cork'N'Bib by Al Fisher BOOK REVIEW 37 Jazz in Britain by Jerry DeMuth BUDD JOHNSON AGELESS JAZZMAN Budd Johnson is one musician who has moved with I was just in my teens when I started playing music, the growth of jazz, from the music of the twenties in Dallas, where my brother Keg and I -were born. -

Ross Russell

Ross Russell: A Preliminary Inventory of an Addition to His Papers at the Harry Ransom Humanities Research Center Descriptive Summary Creator: Russell, Ross, 1909-2000 Title: Ross Russell Addition to His Papers Dates: 1970s-1999 Extent: 11 boxes (4.62 linear feet) Abstract: This addition includes working papers, reserach files, personal and professional correspondence, resumes, chronology, and other biographical material prepared by Russell. Also present are papers relating to Russell's father and wife, property and financial records, personal photographs, travel diaries, and World War II documents. Of particular interest are more than eighty rolls of jazz negatives. Access: Open for research Administrative Information Acquisition: Purchase, 2002 (Reg. no. 14989) Processed by: Liz Murray, 2003 Repository: Harry Ransom Humanities Research Center, The University of Texas at Austin Russell, Ross, 1909-2000 Scope and Contents This addition to the papers of jazz historian Ross Russell contains material remaining in his estate following his death in January 2000. As with previously received Russell material, this collection was prepared for shipment by La Jolla book dealer Laurence McGilvery whose descriptive notes are found throughout. The bulk of the material consists of Russell's project files covering a variety of subjects from notes and sketches for fiction to jazz topics. Although much of the material is undated, it appears that these files were in use during the last years of Russell's life. Russell's folder descriptions are retained and the folders are arranged alphabetically. The materials are organized in three series: Series I. Working Papers and Research Files; Series II. Correspondence, 1980-1999; and Series III. -

'Baptist Beat' in Modern Jazz Modern in Beat' the 'Baptist Addis

Addis: The 'Baptist Beat' in Modern Jazz Texan Gene Ramey in Kansas City & New York” York” in Kansas City & New Gene Ramey Texan in Modern Jazz: ‘Baptist Beat’ “The Produced by The Berkeley Electronic Press, 2004 1 Journal of Texas Music History, Vol. 4 [2004], Iss. 2, Art. 3 Texan Gene Ramey in Kansas City & New York” York” in Kansas City & New Gene Ramey Texan in Modern Jazz: ‘Baptist Beat’ “The Texan Gene Ramey in Kansas City & New York” in Kansas City & New Gene Ramey Texan in Modern Jazz: ‘Baptist Beat’ “The With roots in Texas gospel and blues, Ramey put his stamp Tyler but moved to Austin. Alphonso Trent’s concerts from the on some of the most important music of the era, playing bass Adolphus Hotel in Dallas played on WFAA radio and, over the alongside such musical giants as Charlie Parker, Lester noon hour, Ramey heard the Herman Waldman Band’s “society Young, Billie Holiday, Sonny Rollins, Thelonious Monk, swing” broadcast from the Gunther Hotel in San Antonio. and fellow Texan, Charlie Christian. Ramey had the rare Many of these groups came to be known as “territory ability to play two styles—swing and bebop—and, after bands,” because they normally played within a limited region, his return toTexas in 1976, he reminisced about the role or “territory,” that was usually within a day or two’s drive of a he played in the transition from one to the other. Always “home” radio station, on which they regularly performed. During generous to interviewers, such as Stanley Dance, Ross the 1920s, many of these territory bands congregated in Kansas Russell, François Postif, and Nathan Pearson, Ramey’s City, Kansas. -

The Problem with White Hipness: Race, Gender, And

Monson, Ingrid, MUSIC ANTHROPOLOGIES AND MUSIC HISTORIES: THE PROBLEM WITH WHITE HIPNESS: RACE, GENDER, AND CULTURAL CONCEPTIONS IN JAZZ HISTORICAL DISCOURSE , Journal of the American Musicological Society, 48:3 p.396 THE PROBLEM WITH WHITE HIPNESS 397 After thirty years Amiri Baraka's Blues People remains the classic narrative of jazz as an avant-garde subculture that, in its separation from mainstream popular culture and the black middle class, synthe sized a modern, urban, African American aesthetic fluent in "the formal canons of Western nonconformity."4 In Baraka's account the "autonomous blues"-the essence of African American emotional expressivity-has been in constant danger of dilution due to the conformist and assimilationist demands ofa black middle class that has dictated an "image of a whiter Negro, to the poorer, blacker Ne groes."5 Jazz musicians, by identifying with modernist avant-garde notions of formal and stylistic rebellion, provided a link between the social extremes of the African American community: the "rent-party people" at one end of the scale, and "the various levels of parvenu middle class at the other.I'" Baraka argued that it was possible, through a reciprocal exchange between the modern African American artist and the alienated "young white American intellectual, artist, and Bohemian," to articulate an authentic black expressivity within an urban modernity." This hip subculture, comprising black Americans interested in Western artistic nonconformity and white Americans captivated by urban African American styles of music, dress, and speech, fashioned itself as a vanguard cultural force against the "shoddy cornucopia of popular American culture.T It was an elite of the socially progressive and politically aware that constructed itself as both outside of and above the ordinary American, black or white.