Speculative Fiction

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

285 Summer 2008 SFRA Editors a Publication of the Science Fiction Research Association Karen Hellekson Review 16 Rolling Rdg

285 Summer 2008 SFRA Editors A publication of the Science Fiction Research Association Karen Hellekson Review 16 Rolling Rdg. Jay, ME 04239 In This Issue [email protected] [email protected] SFRA Review Business Big Issue, Big Plans 2 SFRA Business Craig Jacobsen Looking Forward 2 English Department SFRA News 2 Mesa Community College Mary Kay Bray Award Introduction 6 1833 West Southern Ave. Mary Kay Bray Award Acceptance 6 Mesa, AZ 85202 Graduate Student Paper Award Introduction 6 [email protected] Graduate Student Paper Award Acceptance 7 [email protected] Pioneer Award Introduction 7 Pioneer Award Acceptance 7 Thomas D. Clareson Award Introduction 8 Managing Editor Thomas D. Clareson Award Acceptance 9 Janice M. Bogstad Pilgrim Award Introduction 10 McIntyre Library-CD Imagination Space: A Thank-You Letter to the SFRA 10 University of Wisconsin-Eau Claire Nonfiction Book Reviews Heinlein’s Children 12 105 Garfield Ave. A Critical History of “Doctor Who” on Television 1 4 Eau Claire, WI 54702-5010 One Earth, One People 16 [email protected] SciFi in the Mind’s Eye 16 Dreams and Nightmares 17 Nonfiction Editor “Lilith” in a New Light 18 Cylons in America 19 Ed McKnight Serenity Found 19 113 Cannon Lane Pretend We’re Dead 21 Taylors, SC 29687 The Influence of Imagination 22 [email protected] Superheroes and Gods 22 Fiction Book Reviews SFWA European Hall of Fame 23 Fiction Editor Queen of Candesce and Pirate Sun 25 Edward Carmien The Girl Who Loved Animals and Other Stories 26 29 Sterling Rd. Nano Comes to Clifford Falls: And Other Stories 27 Princeton, NJ 08540 Future Americas 28 [email protected] Stretto 29 Saturn’s Children 30 The Golden Volcano 31 Media Editor The Stone Gods 32 Ritch Calvin Null-A Continuum and Firstborn 33 16A Erland Rd. -

International Speculative Fiction

Editorial Fall has come and I must say this is my favourite season. It’s the season of Halloween, of fallen leaves swept by gentle cold breezes. It’s the season Contents to renew old acquaintances back at school, or to return from those tiring holidays abroad and be swept up by the welcome routine of our daily jobs, FICTION: it’s the season before the madness of the end of the year takes hold. 03 ||Metal Can Lanterns It’s also the season to curl up on our favourite chair, with slow crackling JOYCE CHNG embers on the fireplace giving off their heat, a cup of steaming Earl Grey (or another beverage of your preference) nearby and a good story to while 06 || 59 Beads away the night. ROCHITA LOENEN-RUIZ And good stories aplenty is what ISF is all about and it is with the utmost 15 || Hunt beneath the Moon pleasure that I present to you in this #1 of ISF Magazine three outstanding MARIAN TRUŢĂ stories by a very talented roster of international authors. NON-FICTION: From Singapore Ms. Joyce Chng presents us with a short tale of rituals 22 || Philip K. Dick: A Visionary Among long forgotten and the hope that resides, against all odds, in our younger the Charlatans generation. Metal Can Lanterns needs to be read slowly for all its nuances STANISLAW LEM to settle in but the rewards are great and wonderful. Still on the fiction side of our magazine, comes a tale of faustian echoes 02 from the pen of Ms. -

SPJ-Issue-2019-03

2019 ♦ 3 Auslender Bufnilă Crow Dibble Guha Kelly Kriz Lemaire Martín Rodríguez Mina Silva Yoakeim sciphijournal.org ♦ [email protected] 1 CREW CONTENTS Co-editors: 3 Editorial Ádám Gerencsér Mariano Martín Rodríguez 4 « Asymptotic Convergence» Communications: Gina Adela Ding Ramez Yoakeim Webmaster: Ismael Osorio Martín 6 « The Greatest Good to God» Contact: Andy Dibble [email protected] 9 « Byzantine Theology in Alternate History: not such a serious matter?» Pascal Lemaire 16 « Winged Spirit» Luís Filipe Silva Translation and introductory note by Rex Nielson 19 « Peripheric Synthesized» Ava Kelly 22 « Relative Perception» Brishti Guha 26 « New Worlds, Old Worlds» Mina 30 « In Vivo Genome-editing Rescues Damnatio Memoriae in a Mouse Model of Titor Syndrome» Andrea Kriz 34 « A Note on Romanian Science Fiction Literature from Past to Present» Mariano Martín Rodríguez 39 « The Arms of the Gods » Ovidiu Bufnilă Introductory note and translation by Cătălin Badea-Gheracostea 42 « Hyrenas» E.N. Auslender 46 « A Reflection on the Achievement of Gene Wolfe, with Gregorian Chant Echoing Offstage» Blackstone Crow 2 Editorial At the time of writing, Ádám of the SPJ editorial team this heterodox society that oftentimes intimates a is on pilgrimage to the Holy Land. Yet the primary Mediterranean re-imagining of Blade Runner, where impressions his sojourn inspires belong not in the college girls in army uniform carrying assault rifles realm of theology, but world building. (Admittedly, mingle with Haredim and rainbow warriors at the two are related.) retrofuturist malls, has nonetheless managed to forge a sense of identity and purpose. To an avid reader of the fantastic, even a cursory intercourse with the State of Israel reveals it as a prime It even has its own hermetic SF scene in Hebrew, example of applied utopian SF. -

Ideology in the 20Th Century Studies of Literary and Social Discourses and Practices

Ideology in the 20th Century Studies of literary and social discourses and practices Edited by Jonatan Vinkler Ana Beguš Marcello Potocco Založba Univerze na Primorskem University of Primorska Press Uredniški odbor / Editorial Board Gregor Pobežin Maja Meško Vito Vitrih Silva Bratož Ana Petelin Janko Gravner Krstivoje Špijunović Miloš Zelenka Jonatan Vinkler Alen Ježovnik Ideology in the 20th Century Studies of literary and social discourses and practices Edited by Jonatan Vinkler Ana Beguš Marcello Potocco Ideology in the 20th Century: studies of literary and social discourses and practices Edited by Jonatan Vinkler, Ana Beguš and Marcello Potocco Reviewers Jernej Habjan Igor Grdina Typesetting: Jonatan Vinkler Published by Založba Univerze na Primorskem (For publisher: Prof. Klavdija Kutnar, PhD., rector) Titov trg 4, SI-6000 Koper Editor-in-chief Jonatan Vinkler Managing editor Alen Ježovnik Koper 2019 isbn 978-961-7055-99-3 (spletna izdaja: pdf) http://www.hippocampus.si/ISBN/978-961-7055-99-3.pdf isbn 978-961-7055-28-3 (spletna izdaja: html) http://www.hippocampus.si/ISBN/978-961-7055-28-3/index.html DOI: https://doi.org/10.26493/978-961-7055-99-3 © 2019 Založba Univerze na Primorskem/University of Primorska Press Izdaja je sofinancirana po pogodbi ARRS za sofinanciranje izdajanja znanstvenih monografij v letu 2019. Kataložni zapis o publikaciji (CIP) pripravili v Narodni in univerzitetni knjižnici v Ljubljani COBISS.SI-ID=303309312 ISBN 978-961-7055-99-3 (pdf) ISBN 978-961-7055-28-3 (html) Contents Marcello Potocco, Ana Beguš, Jonatan Vinkler 9 Introduction: The Crossroads of Literature and Social Praxis Ana Beguš 19 Genre in the Technological Remediation of Culture 24 New Genres 27 The Status of Literature in the New Media Ecosystem 28 Future Technological and Cultural Development Tomaž Toporišič 33 Negotiating the Discursive Circulation of (Mis)Information in the Face of Global Uncertainties: The Fiction of W. -

Anthology of European Speculative Fiction

ANTHOLOGY OF EUROPEAN SPECULATIVE FICTION Edited by Cristian Tama ş and Roberto Mendes ANTHOLOGY OF EUROPEAN SPECULATIVE FICTION 1 ANTHOLOGY OF EUROPEAN SPECULATIVE FICTION AUTHORS Ian R. MacLeod (England) Jetse de Vries (Netherlands) Regina Catarino (Portugal) Liviu Radu (Romania) Carmelo Rafala (Italy) Cristian Mihail Teodorescu (Romania) Diana Pinguicha (Portugal) Hannu Rajaniemi (Finland) Vladimir Arenev (Ukraine) Philip Harris (England) Dănuţ Ungureanu (Romania) Aliette de Bodard (France) EDITED BY Cristian Tamaş and Roberto Mendes PUBLISHED BY ISF Magazine and Europa SF OTHER CREDITS Cover Design by Saul Bottcher, Copy Editing and ebook formatting by Elizabeth K. Campbell, Slush Reading by Raquel Margato and Alexandra Rolo, PDF preparation by Roberto Mendes. COVER ILLUSTRATION The artwork is named "Galactus" by George Munteanu; ©George Munteanu (all rights reserved), reproduced by the author's permission. Copyrights held by various Authors. This Anthology Is brought to you by ISF MAGAZINE (nominated for an ESFS Award for Best Magazine) and EUROPA SF (nominated for an ESFS Award for Best Site) ANTHOLOGY OF EUROPEAN SPECULATIVE FICTION 2 TABLE OF CONTENTS Introduction by Cristian Tamaş and Roberto Mendes 4 Ian R. MacLeod (England) - The Dead Orchards 6 Jetse de Vries (Netherlands) - Transcendent Express 16 Regina Catarino (Portugal) - Memory Recall 27 Liviu Radu (Romania) - Digits are Cold Numbers are Warm 34 Carmelo Rafala (Italy) - Repeat Performances 50 Cristian Mihail Teodorescu (Romania) - Bing Bing Larissa 63 Diana Pinguicha -

Translating and Reviewing Canadian Sf in Post-Communist Romania

JOURNAL OF ROMANIAN LITERARY STUDIES Issue no. 5/2014 TRANSLATING AND REVIEWING CANADIAN SF IN POST-COMMUNIST ROMANIA. THE CASE OF WILLIAM GIBSON Ana-Magdalena PETRARU ”Al. Ioan Cuza” University of Iași Abstract: This paper examines the Romanian reception of a reputed English Canadian writer of science fiction, William Gibson, via the translations from his novels and the critical studies published in periodicals. Our aim is to establish the place of the SF genre in post- communism, based on the allegations in the Romanian Translation Studies discourse and assess the writer’s role in the Romanian cultural and literary polysystem as compared to other Canadian authors. Keywords: Canadian science fiction, Romanian reception, polysystem theories, Translation Studies Discourse, Romanian periodicals Introduction During post-communist Romania, Canadian literature has flourished due to the set-up of Canadian Studies centres and academic programmes in most universities of the country, not to mention that doctoral theses and academic papers in the field are now published. As tackled by our previous research (Petraru, 2014: 536-537), the increasing interest in Canadian Studies and literature also showed in the higher number of translations from Canadian writers and the criticism devoted to them. If before 2000 works that were unavailable during the communist years were mostly published (not only various cheap sensational novels, but also translations from William Gibson’s SF novels), the new millennium has also seen the publication of translations from novels by important Canadian authors. Furthermore, there are the critical pieces devoted to them, both in periodicals and academic writings that enjoyed book-length treatment; thus, the works of major postmodern Canadian authors such as Margaret Atwood, Leonard Cohen and Michael Ondaatje are usually analysed in individual chapters (cf. -

Foundation the International Review of Science Fiction Foundation 131 the International Review of Science Fiction

Foundation The International Review of Science Fiction Foundation 131 The International Review of Science Fiction In this issue: Emad El-Din Aysha celebrates the work of Hosam El-Zembely Stefan Ekman and Audrey Taylor offer a practical examination of world-building Javier Martinez Jimenez excavates the role of cities in H.P. Lovecraft Fiona Moore and Alan Stevens treat Doctor Who as a postcolonial case study Umberto Rossi listens in to the uses of recorded sound in Philip K. Dick Nina Allan dances to the tune of Keith Roberts’ Pavane Paul Kincaid asks if critics hate everything Christopher Owen interviews Sephora Hosein about the Judith Merril Collection Conference reports by Paul March-Russell, M.J. Ryder, Katie Stone and Agata Waszkiewicz In addition, there are reviews by: Zeynep Anli, Marleen S. Barr, Amandine Faucheux, Rachel Claire Hill, Chris Hussey, E. Leigh McKagen, Sinead Murphy, Chris Pak, Andy Sawyer, Lars Schmeink, Patrick Whitmarsh and Mark P. Williams Of books by: Nik Abnett, Yoshio Aramaki, Gerry Canavan, Giancarlo Genta, James Gunn, Everett Hamner, Ulrike Kuchler, Silja Maehl and Graeme Stout, Jeannette Ng, Michael R. Page, Ahmed Saadawi, John Timberlake, Peter Watts and Henry Wessells Cover image: N.K. Jemisin’s acceptance of the Hugo Award for Best Novel, Worldcon 76, 19 August 2018 N.K. Jemisin : Hugo Triple Award Winner Foundation is published three times a year by the Science Fiction Foundation (Registered Charity no. 1041052). It is typeset and printed by The Lavenham Press Ltd., 47 Water Street, Lavenham, Suffolk, CO10 9RD. Foundation is a peer-reviewed journal Subscription rates for 2019 Individuals (three numbers) United Kingdom £23.00 Europe (inc. -

SFRA Newsletter and SFRA Wiil Be Advertised, but Karen Hellekson Will Serve in Review

University of South Florida Scholar Commons Digital Collection - Science Fiction & Fantasy Digital Collection - Science Fiction & Fantasy Publications 7-1-2008 SFRA ewN sletter 285 Science Fiction Research Association Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarcommons.usf.edu/scifistud_pub Part of the Fiction Commons Scholar Commons Citation Science Fiction Research Association, "SFRA eN wsletter 285 " (2008). Digital Collection - Science Fiction & Fantasy Publications. Paper 99. http://scholarcommons.usf.edu/scifistud_pub/99 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Digital Collection - Science Fiction & Fantasy at Scholar Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Digital Collection - Science Fiction & Fantasy Publications by an authorized administrator of Scholar Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. • Summer 2008 Editors I Karen Hellekson 16 Rolling Rdg. Jay, ME 04239 [email protected] [email protected] SFRA Review Business Big Issue, Big Plans 2 SFRA Business Craig Jacobsen Looking Forward 2 English Department SFRA News 2 Mesa Community College Mary Kay Bray Award Introduction 6 1833 West Southern Ave. Mary Kay Bray Award Acceptance 6 Mesa, AZ 85202 Graduate Student Paper Award Introduction 6 [email protected] Graduate Student Paper Award Acceptance 7 [email protected] Pioneer Award Introduction 7 Pioneer Award Acceptance 7 Thomas D. Clareson Award Introduction 8 Managing Editor Thomas D. Clareson Award Acceptance 9 Janice M. Bogstad -

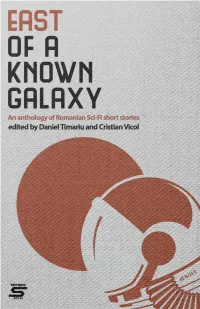

East-Of-A-Known-Galaxy-PDF-FINAL2

EAST OF A KNOWN GALAXY Daniel Timariu şi Cristian Vicol East of a Known Galaxy Copyright © autorii povestirilor Copyright © TRITONIC 2019 pentru ediția prezentă. TRITONIC Str. Coacăzelor, nr. 5, București email: [email protected] www.tritonic.ro Descrierea CIP a Bibliotecii Naționale a României East of a Known Galaxy – An Anthology of Romanian Sci-Fi Short Stories Edited by Daniel Timariu and Cristian Vicol – București: Tritonic Books, 2019 ISBN: 821.135.1 Editors: Daniel Timariu and Cristian Vicol Publisher: Bogdan Hrib Cover: Cristian Vicol Proofreading: Alexandru Maniu Translators: Antuza Genescu (Transformation by Silviu Genescu), Alexandru Maniu (Bodies to Let by Daniel Timariu, and Radio Killed the Video Star by Cristian Vicol), Miloș Dumbraci (Tiger- men by Miloș Dumbraci), Alexandra Pișcu (Cursed Night! By Teodora Matei), J.S. Bangs, Anamaria Bancea, Sebi Simion and Alexandru Maniu (The Dinner by Liviu Surugiu), Alexandru Lamba (Bug by Alexandru Lamba), Lucian-Dragoș Bogdan (The Story of Xieng Baohui by Lucian-Dragoș Bogdan), Florin Purluca (The First Man to Walk on the Moon by Florin Purluca), Cătălina Fometici (Beyond Night’s Veil by Cătălina Fometici), Mălina Duță (Mary Stenton Returns to the Motherland by Lucian-Vasile Szabo), and Andreea Șerban (Serpents among the Scent of Algae by Ciprian-Ionuț Baciu). Copyrights All rights for these stories belong to their respective authors. They may be translated and published in other languages free of copyright, but only after issuing a formal request to the authors. Otherwise, the stories shall not, by way of trade or otherwise, be EAST OF A KNOWN GALAXY An Anthology of Romanian Sci-Fi Short Stories Edited by Daniel Timariu and Cristian Vicol București, 2019 Index A Word from the Editors............................................................................. -

Introduction Hosted at Jokes of Repression Serguei Alex

East European Politics and Societies Volume 25 Number 4 November 2011 655-657 © 2011 SAGE Publications 10.1177/0888325411415846 Introduction http://eeps.sagepub.com hosted at Jokes of Repression http://online.sagepub.com Serguei Alex. Oushakine Princeton University n his Poetics, Aristotle famously defined comedy as “an imitation of inferior people.” IHowever, as the philosopher specified, not every defect is an object of the comic ridicule: “The laughable is an error or disgrace that does not involve pain or destruc- tion: for example, a comic mask is ugly and distorted, but it does not involve pain.”1 Aristotle’s equation of the laughable with painless mockery usefully points to several important aspects of laughter discussed in this cluster. The comic genre provides symbolic mechanisms for simultaneous description of and distancing from the dis- graceful. Yet this (comic) desire to distort and caricature is accompanied by a particu- lar process of affective translation. The disgraceful does not become a cause for disgust or recoil; instead, it acts as an object of scoffing attraction, if not attachment. In a sense, this laughter is a laughter of reconciliation, an acoustic and bodily analgesics—a socially acceptable painkiller that modifies the perception when the perceived situa- tion cannot be changed. Coming from different theoretical and disciplinary perspectives, the authors who contributed to this cluster share the same basic motivation: not unlike Aristotle, they all are interested in understanding the work of the comic outside the usual frame- work of pleasurable entertainment. Socialist comic genres emerge here as jokes of repression, which is to say, as cultural acts that both were produced by mechanisms of artistic censorship and political pressure and, simultaneously, were extremely self-reflective about the emotional proximity to the things being mocked. -

The Functions of Socialist Realism

The Functions of Socialist Realism: Translation of Genre Fiction in Communist Romania S, tefan Baghiu Lucian Blaga University of Sibiu, Romania, 5-7 Victoriei Blvd., Sibiu, 550024, Romania [email protected] Socialist realism has often been perceived as a mass culture movement, but few studies have succeeded in defining its true structure as being mass-addressed. The general view on literature under socialist realism is that of standardized writing and formulaic genre. This paper aims to analyze the genre fiction and subgenres of fiction translated in Romania during socialist realism with a view to acquiring a more comprehensive perspective of the social purpose and functions of socialist realist literature. There have been many attempts to control popular and youth novels in keeping with the ideological program of the USSR and its entire sphere of influence. At the same time, these struggles should be opposed/connected to the development of popular fiction in the Western cultures, as the two opposite cultural systems share several important similarities: if we consider that the most translated authors of fiction within the Stalinist Romanian cultural system were Alexandre Dumas, Jack London and Mark Twain, the gap between Western and Eastern popular fiction would no longer seem so great, while their functions may be opposite. Keywords: literature and ideology / socialist realism / Romania / translation / communism / genre fiction / Eastern Europe / Soviet literature Socialist realism is not entirely made through realism.1 In fact, -

SFRA Newsletter

University of South Florida Scholar Commons Digital Collection - Science Fiction & Fantasy Digital Collection - Science Fiction & Fantasy Publications 4-1-1993 SFRA ewN sletter 204 Science Fiction Research Association Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarcommons.usf.edu/scifistud_pub Part of the Fiction Commons Scholar Commons Citation Science Fiction Research Association, "SFRA eN wsletter 204 " (1993). Digital Collection - Science Fiction & Fantasy Publications. Paper 147. http://scholarcommons.usf.edu/scifistud_pub/147 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Digital Collection - Science Fiction & Fantasy at Scholar Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Digital Collection - Science Fiction & Fantasy Publications by an authorized administrator of Scholar Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. SFRAREVIEW ISSN 1068-39SX EDITOR Daryl F. Mallett ASSOCIATE EDITOR Robert Reginald ASSIST ANT EDITOR Annette Y. Mallett Fiction Editor Daryl F. Mallett Nonfiction Editor Robert Reginald Young Adult Fiction Editor Muriel R. Becker AudiolVideo Editor Michael Klossner Affiliated Products Editor Furumi Sano Editorial Board Paul K. Alkon University of Southern California Muriel R. Becker Montclair State College Elizabeth Chater San Diego State University Robert J. Ewald University of Findlay Joan Gordon Nassau Community College Gary Kern University of California, Riverside Peter Lowentrout California State University, Long Beach Daryl F. Mallett Riverside Community College Frank McConnell University of California, Santa Barbara David G. Mead Corpus Christi State University Robert Reginald California State University, San Bernardino George E. Slusser University of California, Riverside Gary Westfahl University of California, Riverside Milton T. Wolf University of Nevada, Reno SFRA Review is published six times a year by The Science Fiction Research Association, Golden Lion Enterprises, and The Borgo Press.