Inventing the War Crime: an Internal Theory

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

SHERMAN (WILLIAM T.) LETTERS (Mss

SHERMAN (WILLIAM T.) LETTERS (Mss. 1688) Inventory Louisiana and Lower Mississippi Valley Collections Special Collections, Hill Memorial Library Louisiana State University Libraries Baton Rouge, Louisiana State University Reformatted 2003 Revised 2011 SHERMAN (WILLIAM T.) LETTERS Mss. 1688 1863-1905 LSU Libraries Special Collections CONTENTS OF INVENTORY SUMMARY .................................................................................................................................... 3 BIOGRAPHICAL/HISTORICAL NOTE ...................................................................................... 4 SCOPE AND CONTENT NOTE ................................................................................................... 4 CROSS REFERENCES .................................................................................................................. 5 CONTAINER LIST ........................................................................................................................ 6 Use of manuscript materials. If you wish to examine items in the manuscript group, please fill out a call slip specifying the materials you wish to see. Consult the Container List for location information needed on the call slip. Photocopying. If you wish to request photocopies, please consult a staff member. The existing order and arrangement of unbound materials must be maintained. Publication. Readers assume full responsibility for compliance with laws regarding copyright, literary property rights, and libel. Permission to examine archival -

16. the Nuremberg Trials: Nazi Criminals Face Justice

fdr4freedoms 1 16. The Nuremberg Trials: Nazi Criminals Face Justice On a ship off the coast of Newfoundland in August 1941, four months before the United States entered World War II, Franklin D. Roosevelt and British prime minister Winston Churchill agreed to commit themselves to “the final destruction of Nazi tyranny.” In mid-1944, as the Allied advance toward Germany progressed, another question arose: What to do with the defeated Nazis? FDR asked his War Department for a plan to bring Germany to justice, making it accountable for starting the terrible war and, in its execution, committing a string of ruthless atrocities. By mid-September 1944, FDR had two plans to consider. Secretary of the Treasury Henry Morgenthau Jr. had unexpectedly presented a proposal to the president two weeks before the War Department finished its own work. The two plans could not have been more different, and a bitter contest of ideas erupted in FDR’s cabinet. To execute or prosecute? Morgenthau proposed executing major Nazi leaders as soon as they were captured, exiling other officers to isolated and barren lands, forcing German prisoners of war to rebuild war-scarred Europe, and, perhaps most controversially, Defendants and their counsel in the trial of major war criminals before the dismantling German industry in the highly developed Ruhr International Military Tribunal, November 22, 1945. The day before, all defendants and Saar regions. One of the world’s most advanced industrial had entered “not guilty” pleas and U.S. top prosecutor Robert H. Jackson had made his opening statement. “Despite the fact that public opinion already condemns economies would be left to subsist on local crops, a state their acts,” said Jackson, “we agree that here [these defendants] must be given that would prevent Germany from acting on any militaristic or a presumption of innocence, and we accept the burden of proving criminal acts and the responsibility of these defendants for their commission.” Harvard Law School expansionist impulses. -

How Did the Union Fight-And Win-The Civil War? Experts Agree That It Took a Plentiful Supply of the Four M's: Men, Money, Material, and Morale

by Richard c. Brown How did the Union fight-and win-the Civil War? Experts agree that it took a plentiful supply of the Four M's: Men, Money, Material, and Morale. Erie County, New York, played a part in the victory by contributing its share of the 4 M's to the Union cause. The Census of 1860 showed Erie County to have a population of 141,971. Three-fifths of these people lived in the rapidly growing city of Buffalo, where 81,129 persons resided. Amherst had the largest popula- tion of any town in Erie County, 5,084. It was one of only three towns that exceededthree thousand in population, the other two being Clarence and Newstead. Traveling by railroad on his way to his inauguration in Washington, newly-elected President Abraham Lincoln arrived in Buffalo on the afternoon of Saturday, February 16, 1861.After an enthusiastic reception at the railroad station, he and his family were taken to the American Hotel. There they remained overnight. On Saturday afternoon, President-elect Lincoln made a brief and cautious speech to a crowd assembled on the street underneath a balcony of the American Hotel. In the evening he and Mrs. Lincoln greeted hundreds of men and women at receptions held in their honor. The next day they went to church with ex-President Millard Fillmore, Erie County's most distinguished resident. Sunday night the Lincolns con- tinued on their journey. Only a little more than a month after the new President was inaugurated, Confederate guns fired on Fort Sumter. -

Any Victory Not Bathed in Blood: William Rosecrans's Tullahoma

A BGES Civil War Field University Program: Any Victory Not Bathed in Blood: William Rosecrans’s Tullahoma Advance With Jim Ogden June 17–20, 2020; from Murfreesboro, TN “COMPEL A BATTLE ON OUR OWN GROUND?”: William Rosecrans on the objectives of his Tullahoma advance. A “victory not bathed in blood.” A campaign with no major battle. Only a “campaign of maneuver.” You are a real student of the Civil War if you have given serious consideration to this key component of Maj. Gen. William Starke Rosecrans’s command tenure. Sadly, if not entirely overlooked, it usually is only briefly reviewed in histories of the war. Because of the way it did turn out, it is easy to say that it is only a campaign of maneuver, but as originally conceived the Federal army commander intended and expected much more. Henry Halleck’s two “great objects” were still to be achieved. Rosecrans hoped that when he advanced from Murfreesboro, much would be accomplished. In this BGES program we’ll examine what Rosecrans hoped would be a campaign that might include not the but rather his planned “Battle for Chattanooga.” Wednesday, June 17, 2020 6 PM. Gather at our headquarters hotel in Murfreesboro where Jim will introduce you to General Rosecrans, his thinking and combat planning. He is an interesting character whose thinking is both strategic and advanced tactical. He was a man of great capacity and the logic behind this operation, when juxtaposed against the expectations of the national leadership, reveals the depth of Rosecrans’s belief in his ability to deliver decisive results that supported Lincoln’s war objectives. -

Ocm06220211.Pdf

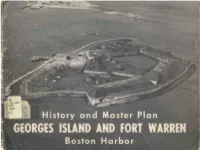

THE COMMONWEALTH OF MASSACHUSETTS--- : Foster F__urcO-lo, Governor METROP--�-��OLITAN DISTRICT COM MISSION; - PARKS DIVISION. HISTORY AND MASTER PLAN GEORGES ISLAND AND FORT WARREN 0 BOSTON HARBOR John E. Maloney, Commissioner Milton Cook Charles W. Greenough Associate Commissioners John Hill Charles J. McCarty Prepared By SHURCLIFF & MERRILL, LANDSCAPE ARCHITECTS BOSTON, MASSACHUSETTS HISTORICAL AND BIOGRAPHICAL CONSULTANT MINOR H. McLAIN . .. .' MAY 1960 , t :. � ,\ �:· !:'/,/ I , Lf; :: .. 1 1 " ' � : '• 600-3-60-927339 Publication of This Document Approved by Bernard Solomon. State Purchasing Agent Estimated cost per copy: $ 3.S2e « \ '< � <: .' '\' , � : 10 - r- /16/ /If( ��c..c��_c.� t � o� rJ 7;1,,,.._,03 � .i ?:,, r12··"- 4 ,-1. ' I" -po �� ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS We wish to acknowledge with thanks the assistance, information and interest extended by Region Five of the National Park Service; the Na tional Archives and Records Service; the Waterfront Committee of the Quincy-South Shore Chamber of Commerce; the Boston Chapter of the United Daughters of the Confederacy; Lieutenant Commander Preston Lincoln, USN, Curator of the Military Order of the Loyal Legion; Mr. Richard Parkhurst, former Chairman of Boston Port Authority; Brigardier General E. F. Periera, World War 11 Battery Commander at Fort Warren; Mr. Edward Rowe Snow, the noted historian; Mr. Hector Campbel I; the ABC Vending Company and the Wilson Line of Massachusetts. We also wish to thank Metropolitan District Commission Police Captain Daniel Connor and Capt. Andrew Sweeney for their assistance in providing transport to and from the Island. Reproductions of photographic materials are by George M. Cushing. COVER The cover shows Fort Warren and George's Island on January 2, 1958. -

Excerpt from Elizabeth Borgwardt, the Nuremberg Idea: “Thinking Humanity” in History, Law & Politics, Under Contract with Alfred A

Excerpt from Elizabeth Borgwardt, The Nuremberg Idea: “Thinking Humanity” in History, Law & Politics, under contract with Alfred A. Knopf. DRAFT of 10/24/16; please do not cite or quote without author’s permission Human Rights Workshop, Schell Center for International Human Rights, Yale Law School November 3, 2016, 12:10 to 1:45 pm, Faculty Lounge Author’s Note: Thank you in advance for any attention you may be able to offer to this chapter in progress, which is approximately 44 double-spaced pages of text. If time is short I recommend starting with the final section, pp. 30-42. I look forward to learning from your reactions and suggestions. Chapter Abstract: This history aims to show how the 1945-49 series of trials in the Nuremberg Palace of Justice distilled the modern idea of “crimes against humanity,” and in the process established the groundwork for the modern international human rights regime. Over the course of the World War II era, a 19th century version of crimes against humanity, which might be rendered more precisely in German as Verbrechen gegen die Menschlichkeit (crimes against “humane-ness”), competed with and was ultimately co-opted by a mid-20th- century conception, translated as Verbrechen gegen die Menschheit (crimes against “human- kind”). Crimes against humaneness – which Hannah Arendt dismissed as “crimes against kindness” – were in effect transgressions against traditional ideas of knightly chivalry, that is, transgressions against the humanity of the perpetrators. Crimes against humankind – the Menschheit version -- by contrast, focused equally on the humanity of victims. Such extreme atrocities most notably denied and attacked the humanity of individual victims (by denying their human rights, or in Arendt’s iconic phrasing, their “right to have rights”). -

Warfare in a Fragile World: Military Impact on the Human Environment

Recent Slprt•• books World Armaments and Disarmament: SIPRI Yearbook 1979 World Armaments and Disarmament: SIPRI Yearbooks 1968-1979, Cumulative Index Nuclear Energy and Nuclear Weapon Proliferation Other related •• 8lprt books Ecological Consequences of the Second Ihdochina War Weapons of Mass Destruction and the Environment Publish~d on behalf of SIPRI by Taylor & Francis Ltd 10-14 Macklin Street London WC2B 5NF Distributed in the USA by Crane, Russak & Company Inc 3 East 44th Street New York NY 10017 USA and in Scandinavia by Almqvist & WikseH International PO Box 62 S-101 20 Stockholm Sweden For a complete list of SIPRI publications write to SIPRI Sveavagen 166 , S-113 46 Stockholm Sweden Stoekholol International Peace Research Institute Warfare in a Fragile World Military Impact onthe Human Environment Stockholm International Peace Research Institute SIPRI is an independent institute for research into problems of peace and conflict, especially those of disarmament and arms regulation. It was established in 1966 to commemorate Sweden's 150 years of unbroken peace. The Institute is financed by the Swedish Parliament. The staff, the Governing Board and the Scientific Council are international. As a consultative body, the Scientific Council is not responsible for the views expressed in the publications of the Institute. Governing Board Dr Rolf Bjornerstedt, Chairman (Sweden) Professor Robert Neild, Vice-Chairman (United Kingdom) Mr Tim Greve (Norway) Academician Ivan M£ilek (Czechoslovakia) Professor Leo Mates (Yugoslavia) Professor -

Library Company of Philadelphia Mca 5792.F CIVIL WAR LEADERS

Library Company of Philadelphia McA 5792.F CIVIL WAR LEADERS EPHEMERA COLLECTION 1860‐1865 1.88 linear feet, 2 boxes Series I. Small Ephemera, 1860‐1865 Series II. Oversize Material, 1860s March 2006 McA MSS 004 2 Descriptive Summary Repository Library Company of Philadelphia 1314 Locust Street, Philadelphia, PA 19107‐5698 Call Number McA 5792.F Creator McAllister, John A. (John Allister), 1822‐1896. Title Civil War Leaders Ephemera Collection Inclusive Dates 1860‐1865 Quantity 1.88 linear feet (2 boxes) Language of Materials Materials are in English. Abstract The Civil War Leaders Ephemera Collection holds ephemera and visual materials related to a group of prominent American politicians and military heroes active in the middle of the nineteenth century: Robert Anderson, William G. Brownlow, Jefferson Davis, Abraham Lincoln, George B. McClellan, and Winfield Scott. Administrative Information Restrictions to Access The collection is open to researchers. Acquisition Information Gift of John A. McAllister; forms part of the McAllister Collection. Processing Information The Civil War Leaders Ephemera Collection was formerly housed in four folio albums that had been created after the McAllister Collection arrived at the Library Company. The material was removed from the albums, arranged, and described in 2006, under grants from the National Endowment for the Humanities and the William Penn Foundation. The collection was processed by Sandra Markham. Any views, findings, conclusions or recommendations expressed in this finding aid do not necessarily represent those of the National Endowment for the Humanities. Preferred Citation This collection should be cited as: [indicate specific item or series here], Civil War Leaders Ephemera Collection (McA 5792.F), McAllister Collection, The Library Company of Philadelphia. -

Principal Fortifications of the United States (1870–1875)

Principal Fortifications of the United States (1870–1875) uring the late 18th century and through much of the 19th century, army forts were constructed throughout the United States to defend the growing nation from a variety of threats, both perceived and real. Seventeen of these sites are depicted in a collection painted especially for Dthe U.S. Capitol by Seth Eastman. Born in 1808 in Brunswick, Maine, Eastman found expression for his artistic skills in a military career. After graduating from the U.S. Military Academy at West Point, where offi cers-in-training were taught basic drawing and drafting techniques, Eastman was posted to forts in Wisconsin and Minnesota before returning to West Point as assistant teacher of drawing. Eastman also established himself as an accomplished landscape painter, and between 1836 and 1840, 17 of his oils were exhibited at the National Academy of Design in New York City. His election as an honorary member of the academy in 1838 further enhanced his status as an artist. Transferred to posts in Florida, Minnesota, and Texas in the 1840s, Eastman became interested in the Native Americans of these regions and made numerous sketches of the people and their customs. This experience prepared him for his next five years in Washington, D.C., where he was assigned to the commissioner of Indian Affairs and illus trated Henry Rowe Schoolcraft’s important six-volume Historical and Statistical Information Respecting the History, Condition, and Prospects of the Indian Tribes of the United States. During this time Eastman also assisted Captain Montgomery C. Meigs, superintendent of the Capitol Brevet Brigadier General Seth Eastman. -

Sherman's March and Georgia's Refugee Slaves Ben Parten Clemson University, [email protected]

Clemson University TigerPrints All Theses Theses 5-2017 "Somewhere Toward Freedom:" Sherman's March and Georgia's Refugee Slaves Ben Parten Clemson University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://tigerprints.clemson.edu/all_theses Recommended Citation Parten, Ben, ""Somewhere Toward Freedom:" Sherman's March and Georgia's Refugee Slaves" (2017). All Theses. 2665. https://tigerprints.clemson.edu/all_theses/2665 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Theses at TigerPrints. It has been accepted for inclusion in All Theses by an authorized administrator of TigerPrints. For more information, please contact [email protected]. “SOMEWHERE TOWARD FREEDOM:” SHERMAN’S MARCH AND GEORGIA’S REFUGEE SLAVES A Thesis Presented to the Graduate School of Clemson University In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Masters of Arts History by Ben Parten May 2017 Accepted by: Dr. Vernon Burton, Committee Chair Dr. Lee Wilson Dr. Rod Andrew ABSTRACT When General William T. Sherman’s army marched through Georgia during the American Civil War, it did not travel alone. As many as 17,000 refugee slaves followed his army to the coast; as many, if not more, fled to the army but decided to stay on their plantations rather than march on. This study seeks to understand Sherman’s march from their point of view. It argues that through their refugee experiences, Georgia’s refugee slaves transformed the march into one for their own freedom and citizenship. Such a transformation would not be easy. Not only did the refugees have to brave the physical challenges of life on the march, they had to also exist within a war waged by white men. -

Criminal Prosecution of UN Peacekeepers: When Defenders of Peace Incite Further Conflict Through Their Own Misconduct

American University International Law Review Volume 33 Issue 1 Article 3 2017 Criminal Prosecution of UN Peacekeepers: When Defenders of Peace Incite Further Conflict Through Their Own Misconduct Shayna Ann Giles Baker, Donelson, Bearman, Caldwell & Berkowitz Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.wcl.american.edu/auilr Part of the Human Rights Law Commons, International Humanitarian Law Commons, and the International Law Commons Recommended Citation Giles, Shayna Ann (2017) "Criminal Prosecution of UN Peacekeepers: When Defenders of Peace Incite Further Conflict Through Their Own Misconduct," American University International Law Review: Vol. 33 : Iss. 1 , Article 3. Available at: https://digitalcommons.wcl.american.edu/auilr/vol33/iss1/3 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Washington College of Law Journals & Law Reviews at Digital Commons @ American University Washington College of Law. It has been accepted for inclusion in American University International Law Review by an authorized editor of Digital Commons @ American University Washington College of Law. For more information, please contact [email protected]. CRIMINAL PROSECUTION OF UN PEACEKEEPERS: WHEN DEFENDERS OF PEACE INCITE FURTHER CONFLICT THROUGH THEIR OWN MISCONDUCT * SHAYNA ANN GILES I. INTRODUCTION........................................................................148 II. WITH GREAT POWER COMES GREAT RESPONSIBILITY: THE DEVELOPMENT OF THE UNITED NATIONS AND UN PEACEKEEPING...................151 A. THE UNITED NATIONS -

MODIFICATIONS and WAIVERS to TAKING the OATH of ALLEGIANCE Practice Advisory

Practice Advisory | May 2018 MODIFICATIONS AND WAIVERS TO TAKING THE OATH OF ALLEGIANCE Practice Advisory By Sharon Hing I. Introduction The final step in the naturalization process is the oath of allegiance to the United States. The oath demonstrates loyalty to the United States and the Constitution. All applicants must demonstrate that they are “attached to the principles of the Constitution of the United States and well disposed to the good order and happiness of the United States.”1 The oath also includes statements that the applicant is willing to “bear arms on behalf of the United States,” and “perform noncombatant service in the Armed Forces” when required by law.2 Although the text of the oath is included in the naturalization application form, and a United States Citizenship and Immigration Services (USCIS) officer reviews the text of the oath with the applicant at the naturalization interview, a person is not a United States citizen until they have taken the oath. Applicants may request modifications to the oath of allegiance in select circumstances. In other instances, applicants may request to waive taking the oath altogether. In this practice advisory, we outline the requirements for each. A. Waivers to the Oath Requirement USCIS may waive taking the oath of allegiance in two instances: (1) when the applicant is a child; or (2) when the applicant has a physical or development disability or mental impairment. 1. Children In the main, a person cannot naturalize unless they are 18 years of age or older. However, there are several ways that a child can become a U.S.