Night Drive by Will. F. Jenkins Madge Was All Ready and in the Act Of

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Globalization of K-Pop: the Interplay of External and Internal Forces

THE GLOBALIZATION OF K-POP: THE INTERPLAY OF EXTERNAL AND INTERNAL FORCES Master Thesis presented by Hiu Yan Kong Furtwangen University MBA WS14/16 Matriculation Number 249536 May, 2016 Sworn Statement I hereby solemnly declare on my oath that the work presented has been carried out by me alone without any form of illicit assistance. All sources used have been fully quoted. (Signature, Date) Abstract This thesis aims to provide a comprehensive and systematic analysis about the growing popularity of Korean pop music (K-pop) worldwide in recent years. On one hand, the international expansion of K-pop can be understood as a result of the strategic planning and business execution that are created and carried out by the entertainment agencies. On the other hand, external circumstances such as the rise of social media also create a wide array of opportunities for K-pop to broaden its global appeal. The research explores the ways how the interplay between external circumstances and organizational strategies has jointly contributed to the global circulation of K-pop. The research starts with providing a general descriptive overview of K-pop. Following that, quantitative methods are applied to measure and assess the international recognition and global spread of K-pop. Next, a systematic approach is used to identify and analyze factors and forces that have important influences and implications on K-pop’s globalization. The analysis is carried out based on three levels of business environment which are macro, operating, and internal level. PEST analysis is applied to identify critical macro-environmental factors including political, economic, socio-cultural, and technological. -

Summertime Blues

Summertime Blues Senator Tom Coburn, M.D. Senator John McCain 100 stimulus projects that give taxpayers the blues August 2010 coburn.senate.gov mccain.senate.gov Summertime Blues Cover Photo: Interior windows at the now-closed Coldwater Ridge Visitor Center overlooking Mount St. Helens. Courtesy of the National Park Service. 2 Summertime Blues Table of Contents Introduction ........................................................................................................................................................................... 4 1. Forest Service to Replace Windows in Visitor Center Closed in 2007 (Amboy, WA) - $554,763 ..................................................................................................................................................................... 5 2. “Dance Draw” - Interactive Dance Software Development (Charlotte, NC) - $762,372 ............ 6 3. North Shore Connector to Professional Sports Stadiums, Casino (Pittsburgh, PA) - $62 million ........................................................................................................................................................................ 7 4. FEMA Stalls Two Texas Fire Stations More Than a Year, Increases Costs (San Antonio, TX) - $7.3 million ..................................................................................................................................................... 9 5. Abandoned Train Station Converted Into Museum (Glassboro, NJ) - $1.2 million ................... 10 6. Ants Talk. Taxpayers -

1715 Total Tracks Length: 87:21:49 Total Tracks Size: 10.8 GB

Total tracks number: 1715 Total tracks length: 87:21:49 Total tracks size: 10.8 GB # Artist Title Length 01 Adam Brand Good Friends 03:38 02 Adam Harvey God Made Beer 03:46 03 Al Dexter Guitar Polka 02:42 04 Al Dexter I'm Losing My Mind Over You 02:46 05 Al Dexter & His Troopers Pistol Packin' Mama 02:45 06 Alabama Dixie Land Delight 05:17 07 Alabama Down Home 03:23 08 Alabama Feels So Right 03:34 09 Alabama For The Record - Why Lady Why 04:06 10 Alabama Forever's As Far As I'll Go 03:29 11 Alabama Forty Hour Week 03:18 12 Alabama Happy Birthday Jesus 03:04 13 Alabama High Cotton 02:58 14 Alabama If You're Gonna Play In Texas 03:19 15 Alabama I'm In A Hurry 02:47 16 Alabama Love In the First Degree 03:13 17 Alabama Mountain Music 03:59 18 Alabama My Home's In Alabama 04:17 19 Alabama Old Flame 03:00 20 Alabama Tennessee River 02:58 21 Alabama The Closer You Get 03:30 22 Alan Jackson Between The Devil And Me 03:17 23 Alan Jackson Don't Rock The Jukebox 02:49 24 Alan Jackson Drive - 07 - Designated Drinke 03:48 25 Alan Jackson Drive 04:00 26 Alan Jackson Gone Country 04:11 27 Alan Jackson Here in the Real World 03:35 28 Alan Jackson I'd Love You All Over Again 03:08 29 Alan Jackson I'll Try 03:04 30 Alan Jackson Little Bitty 02:35 31 Alan Jackson She's Got The Rhythm (And I Go 02:22 32 Alan Jackson Tall Tall Trees 02:28 33 Alan Jackson That'd Be Alright 03:36 34 Allan Jackson Whos Cheatin Who 04:52 35 Alvie Self Rain Dance 01:51 36 Amber Lawrence Good Girls 03:17 37 Amos Morris Home 03:40 38 Anne Kirkpatrick Travellin' Still, Always Will 03:28 39 Anne Murray Could I Have This Dance 03:11 40 Anne Murray He Thinks I Still Care 02:49 41 Anne Murray There Goes My Everything 03:22 42 Asleep At The Wheel Choo Choo Ch' Boogie 02:55 43 B.J. -

Alan Jackson

COUNCIL FILE NO. /0~051-7 COUNCIL DISTRICT NO. 13 .,/ APPROVAL FOR ACCELERATED PROCESSING DIRECT TO CITY COUNCIL The attached Council File may be processed directly to Council pursuant to the procedure approved June 26, 1990, (CF 83-1 075-S 1) without being referred to the Public Works Committee because the action on the file checked below is deemed to be routine and/or administrative in nature: _} A. Future Street Acceptance. _} B. Quitclaim of Easement(s). _} C. Dedication of Easement(s). _} D. Release of Restriction(s). _x} E. Request for Star in Hollywood Walk of Fame. _} F. Brass Plaque(s) in San Pedro Sport Walk. _} G. Resolution to Vacate or Ordinance submitted in response to Council action. _} H. Approval of plans/specifications submitted by Los Angeles County Flood Control District. APPROVAL/DISAPPROVAL FOR ACCELERATED PROCESSING: APPROVED DISAPPROVED* 1. Council Office of the District 2. Public Works Committee Chairperson *DISAPPROVED FILES WILL BE REFERRED TO THE PUBLIC WORKS COMMITTEE. Please return to Council Index Section, Room 615 City Hall City Clerk Processing: Date notice and report copy mailed to interested parties advising of Council date for this item. Date scheduled in Council. AFTER COUNCIL ACTION: ____J Send copy of adopted report to the Real Estate Section, Development Services Division, Bureau of Engineering (Mail Stop No. 515) for further processing. ___}Other: PLEASE DO NOT DETACH THIS APPROVAL SHEET FROM THE COUNCIL FILE ACCELERATED REVIEW PROCESS- E Office ofthe City Engineer Los Angeles, California To the Honorable Council Of the City of Los Angeles > MAR 2 5 211111 Honorable Members: C. -

STAFFORD COUNTY PLANNING COMMISSION MINUTES October 25, 2017

STAFFORD COUNTY PLANNING COMMISSION MINUTES October 25, 2017 The meeting of the Stafford County Planning Commission of Wednesday, October 25, 2017, was called to order at 6:30 p.m. by Chairman Tom Coen in the Board of Supervisors Chambers of the George L. Gordon, Jr., Government Center. MEMBERS PRESENT: Tom Coen, Crystal Vanuch, Sherry Bailey, Steven Apicella, Roy Boswell, Darrell English, Mike Rhodes MEMBERS ABSENT: None STAFF PRESENT: Jeff Harvey, Rysheda McClendon, Stacie Stinnette, Susan Blackburn DECLARATIONS OF DISQUALIFICATION Mr. Coen: Do we have any declarations of disqualifications? Seeing none, and nobody has indicated any type of change in the agenda. We move onto our Public Presentations. At this point in time, we normally have 3 minutes for the public to come and speak. When you come up to the podium you have 3 minutes. Please state your name and your address. This is an opportunity to speak on any item other than the public hearing item for the evening; so that’s item number 1. Please state your name. You have 3 minutes when the green light turns on. When you hit the yellow light that means you have 1 minute left. And then when you see the red light, we ask you to wrap up your comments. If anyone would like to speak, please come forward at this time. Alright, so we close the public comment period. So now we have a presentation from Ms. Kim McClellan. So Mr. Harvey, would you like to introduce? PUBLIC PRESENTATIONS Stafford County Housing Study by Kim McClellan, Public Policy Director, Fredericksburg Area Association of Realtors Mr. -

The Memory Bridge Training Retreats

1 THE MEMORY BRIDGE TRAINING RETREATS: AN ETHNOGRAPHIC EVALUATION Lucinda Carspecken Lecturer, Inquiry Methodology Indiana University, Bloomington Copyright © June, 2018, L. Carspecken Based on interviews with… Gina Awad Marigrace Becker Christiane Bomhard Debbie Carriveau Angela Christie Heather Comstock Carolyn Cook Emily Cousins Jill Crunkleton Greg Farrell Brenda Gurung Mary Jo Gibbons Jane Harlan-Simmons Ryan Harrison Emma Jack Maeve Larkin Jeanene Lindsey Pat McDaniels Sarah Neary Donna Newman-Bluestein Molly O’Brien Julia Periello Maegan (Maggie) Pollard Magdalena Schamberger Natalie Sell Susan Shifrin Stuart Torrance Michael Verde Cheryl Yeend 2 ACKNOWLEDGMENTS Thanks to my skilled and patient transcribers, Kathleen Carspecken, Sunil Carspecken and Michelle Collard. And thanks to Indiana University’s Faculty Writing Group for providing a weekly space and time to work on this report. 3 TABLE OF CONTENTS INTRODUCTION: THE MEMORY BRIDGE TRAINING RETREATS FOR 2015 AND 2016 5 Memory Bridge in Context: Dementia Care in the United States 6 Research Methods 10 An Overview of the Report 16 CHAPTER 1. MEMORY BRIDGE’S BEGINNINGS, ITS VISION AND SOME ASPECTS OF ITS PHILOSOPHY 18 CHAPTER 2. “INGREDIENTS IN A CASSEROLE”: THE PEOPLE WHO CAME AND WHAT THEY BROUGHT WITH THEM 27 The Selection Criteria 27 The Application Process 30 The Participants 33 Learning from One Another 35 What the Participants Brought with Them 38 CHAPTER 3: THE ELEMENTS OF THE CURRICULUM 63 The Material Aspects of “Feeding the Feeders” 63 Circles 68 Meditation 76 The Buddy Visits 79 Formal Presentations 100 Stories 108 Down Time 113 Group Activities Initiated by Trainees 118 Eye Contact 122 4 CHAPTER 4. -

The Hitchhiker” Series: Mercury Theatre Show: the Hitchhiker Date: Jun 21 1946 by Lucille Fletcher

“The Hitchhiker” Series: Mercury Theatre Show: The Hitchhiker Date: Jun 21 1946 by Lucille Fletcher CAST: Ronald Adams (Narrator) Storekeeper Operator 2 Mrs. Adams Woman Mrs. Whitney Hitchhiker (male) Hitchhiker (female) Gas Station Attendant Operator 1 Announcer: The Columbia Network takes pleasure in bringing you...Suspense! Suspense!-- Columbia’s parade of outstanding thrillers produced and directed by William Spier and scored by Bernard Herman. The notable melodramas from stage and screen, fiction and radio, presented each week to bring you to the edge of your chair, to keep you in...Suspense! Good evening, this is Orson Welles, and very happy I am to be back in the United States and back on the Columbia Network, even for so short a visit as this one--back with old friends like Johnny Dietz, who’s tonight’s director, and Bernard Herrmann. The Mercury Theater presented tonight’s radio play for the first time last year, and we came out right then and hailed it as a classic of the media. Nobody argued the point, a lot of people asked us to do it again, so it’s gratifying to get the chance now and to find a favorite of ours in this distinguished anthology of spook shows. SOUND: (AUTO DRIVES BY) ADAMS: I'm in an auto camp on Route 66 just west of Gallup, New Mexico. If I tell it, perhaps it'll help me -- keep me from going - going crazy. I gotta tell this quickly. I'm not crazy now - I feel perfectly well, except that I'm running a slight temperature. -

Testimonies of Coordinated Stalking by Multiple Persons from California Residents and Former California Residents

Testimonies of Coordinated Stalking by Multiple Persons from California Residents and Former California Residents Testimonies of 90 persons include: • Results of reporting the crimes to law enforcement • Results from visits to mental health professionals • Net results on victim’s lives as a result of the crimes !1 Date: 7/17/19 Your Full Name: Ilona Gazarova City: San Francisco Zip Code: 94103 Please write a brief summary of your experience with coordinated stalking only: I'm systematically subjected to organized stalking, surveillance and harassment by people in my neighborhood and countless individuals whenever I leave my home. I am followed on the streets, to stores, parks, restaurants, public restrooms, doctor appointments, and every other place I go to. I was under surveillance and bullied at three different places of employment. I am also stalked by perpetrators in vehicles. Tracking appears to be accomplished with the help of devices the perpetrators carry in backpacks, by watching, and use of cell phones which they always have in hand and often point in my direction. When going places I looked up online or mentioned in a phone conversation, there will be people standing around that place when I arrive, all looking directly at me, with cellphones in hand. If I'm walking into a building, two to three of those waiting, will walk in with me. These perpetrators often make eye contact to let me know I'm being watched. I have constant interference with normal flow of daily life, making almost every task difficult or impossible. Perpetrators can access all of my online communication, bank and credit card statements, my online medical record, pharmacy prescriptions, cell phone texts, and listen to all conversations. -

Alan Jackson Drive Mp3, Flac, Wma

Alan Jackson Drive mp3, flac, wma DOWNLOAD LINKS (Clickable) Genre: Folk, World, & Country Album: Drive Country: Europe Released: 2002 Style: Country MP3 version RAR size: 1345 mb FLAC version RAR size: 1763 mb WMA version RAR size: 1754 mb Rating: 4.2 Votes: 244 Other Formats: MP4 WAV AHX ADX AU MPC MP2 Tracklist Hide Credits 1 Drive (For Daddy Gene) A Little Bluer Than That 2 Written-By – Irene Kelley, Mark Irwin Bring On The Night 3 Written-By – Alan Jackson , Charlie Craig, Keith Stegall 4 Work In Progress 5 The Sounds Designated Drinker 6 Featuring [A Duet With] – George Strait 7 Where Were You (When The World Stopped Turning) That'd Be Alright 8 Written-By – Mark D. Sanders, Tia Sillers, Tim Nichols 9 Once In A Lifetime Love 10 When Love Comes Around I Slipped And Fell In Love 11 Written-By – Harley Allen, John Wiggins 12 First Love Bonus Track 13 Where Were You (When The World Stopped Turning) (Live) Companies, etc. Phonographic Copyright (p) – BMG Entertainment Copyright (c) – BMG Entertainment Manufactured By – BMG Distribution Distributed By – BMG Distribution Credits Producer – Keith Stegall Written-By – Alan Jackson Notes Also available on cassette Track 13: Live performance from the 35th Annual CMA Awards Mde in the EU. Barcode and Other Identifiers Barcode: 0 78636 70392 3 Label Code: LC 03484 Other versions Category Artist Title (Format) Label Category Country Year Alan Drive (HDCD, Arista 07863-67039-2 07863-67039-2 US 2002 Jackson Album) Nashville Arista 07863-67039-2, Alan Drive (HDCD, Nashville, 07863-67039-2, US 2002 -

Waters to the Sea Activity and Study Guide Version 1.0 2004

WATERS TO THE SEA ACTIVITY AND STUDY GUIDE VERSION 1.0 2004 CENTER FOR GLOBAL ENVIRONMENTAL EDUCATION HAMLINE UNIVERSITY GRADUATE SCHOOL OF EDUCATION WITH UPPER CHATTAHOOCHEE RIVERKEEPER AND OXBOW MEADOWS ENVIRONMENTAL LEARNING CENTER, COLUMBUS STATE UNIVERSITY Activity & Study Guide WATERS TO THE SEA STUDY GUIDE Executive Producers: Tracy Fredin, Kristi Hastie and Becky Champion Producer: John Shepard, Writers: Laurie Allmann and Lori Forkner, Layout: Erika Backberg CONTACT INFORMATION The Center for Global Environmental Education Hamline University MS A1760 1536 Hewitt Avenue, St. Paul, MN 55104 Phone: 651-523-2480 • Web site: http://cgee.haline.edu Upper Chattahoochee Riverkeeper 3 Puritan Mill, 916 Joseph Lowery Blvd. NW Atlanta, GA 30318 Phone: 404-352-9828 • Web site: http://www.ucriverkeeper.org Oxbow Meadows Environmental Learning Center Columbus State University 3535 South Lumpkin Road Columbus, GA 31901 Phone: 706-687-4090 • Web site: http://oxbow.colstate.edu/ SPONSORS The Coca-Cola Company, The Arthur M. Blank Foundation, Georgia Power, Sustainable Forestry Initiative, The Richard C. Munroe Foundation and The Robert Woodruff Foundation 2 Activity & Study Guide Table of Contents Introduction Section 1: Understanding Watersheds 6 Section 2: Ecosystem Introduction 7 Section 3: Testing for Water Quality 8 The Chattahoochee River: An Overview 10 Navigating the CD ROM Program Overview Flow Chart 12 Mountain Region Journey Flow Chart 13 Piedmont Region Journey Flow Chart 14 Coastal Region Journey Flow Chart 15 Technical Support Frequenty -

“Amarillo by Morning” the Life and Songs of Terry Stafford 1

In the early months of 1964, on their inaugural tour of North America, the Beatles seemed to be everywhere: appearing on The Ed Sullivan Show, making the front cover of Newsweek, and playing for fanatical crowds at sold out concerts in Washington, D.C. and New York City. On Billboard magazine’s April 4, 1964, Hot 100 2 list, the “Fab Four” held the top five positions. 28 One notch down at Number 6 was “Suspicion,” 29 by a virtually unknown singer from Amarillo, Texas, named Terry Stafford. The following week “Suspicion” – a song that sounded suspiciously like Elvis Presley using an alias – moved up to Number 3, wedged in between the Beatles’ “Twist and Shout” and “She Loves You.”3 The saga of how a Texas boy met the British Invasion head-on, achieving almost overnight success and a Top-10 hit, is one of triumph and “Amarillo By Morning” disappointment, a reminder of the vagaries The Life and Songs of Terry Stafford 1 that are a fact of life when pursuing a career in Joe W. Specht music. It is also the story of Stafford’s continuing development as a gifted songwriter, a fact too often overlooked when assessing his career. Terry Stafford publicity photo circa 1964. Courtesy Joe W. Specht. In the early months of 1964, on their inaugural tour of North America, the Beatles seemed to be everywhere: appearing on The Ed Sullivan Show, making the front cover of Newsweek, and playing for fanatical crowds at sold out concerts in Washington, D.C. and New York City. -

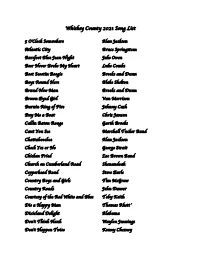

Whiskey County 2021 Song List

Whiskey County 2021 Song List 5 O'Clock Somewhere Alan Jackson Atlantic City Bruce Springsteen Barefoot Blue Jean Night Jake Owen Beer Never Broke My Heart Luke Combs Boot Scootin Boogie Brooks and Dunn Boys Round Here Blake Shelton Brand New Man Brooks and Dunn Brown Eyed Girl Van Morrison Burnin Ring of Fire Johnny Cash Buy Me a Boat Chris Janson Callin Baton Rouge Garth Brooks Cant You See Marshall Tucker Band Chattahoochee Alan Jackson Check Yes or No George Strait Chicken Fried Zac Brown Band Church on Cumberland Road Shenandoah Copperhead Road Steve Earle Country Boys and Girls Tim McGraw Country Roads John Denver Courtesy of the Red White and Blue Toby Keith Die a Happy Man Thomas Rhett` Dixieland Delight Alabama Don’t Think Hank Waylon Jennings Don’t Happen Twice Kenny Chesney Dont Rock the Juke Box Alan Jackson Drive Alan Jackson Drink In My Hand Eric Church Drivin My Life Away Eddie Rabbit Dust on the Bottle David Lee Murphy East Bound And Down Jerry Reed Family Tradition Hank Jr. Fast as You Dwight Yoakam Feathered Indians Tyler Childers Fire on the Mountain Marshall Tucker Band Fishin in the Dark Nitty Gritty Dirt Band Folsom Prison Blues Johnny Cash Free Bird Lynyrd Skynyrd Free Fallin Tom Petty Friends In Low Places Garth Brooks Georgia on a Fast Train Billy Joe Shaver Gin and Juice Snoop Dog Give It All We Got Tonight George Strait Give Me That Girl Joe Nichols Gone Country Alan Jackson Good Directions Billy Currington Good One Comin On David Lee Murphy Heartbreak Hotel Elvis Honkytonk Women Rolling Stones How Country Feels