Cenozoic Paleobotany of the John Day Basin, Central Oregon

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

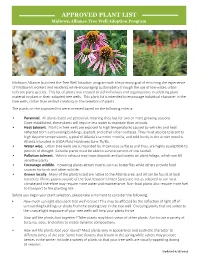

APPROVED PLANT LIST Midtown Alliance Tree Well Adoption Program

APPROVED PLANT LIST Midtown Alliance Tree Well Adoption Program Midtown Alliance launched the Tree Well Adoption program with the primary goal of enriching the experience of Midtown’s workers and residents while encouraging sustainability through the use of low-water, urban tolerant plant species. This list of plants was created to aid individuals and organizations in selecting plant material to plant in their adopted tree wells. This plant list is intended to encourage individual character in the tree wells, rather than restrict creativity in the selection of plants. The plants on the approved list were selected based on the following criteria: • Perennial. All plants listed are perennial, meaning they last for two or more growing seasons. Once established, these plants will require less water to maintain than annuals. • Heat tolerant. Plants in tree wells are exposed to high temperatures caused by vehicles and heat reflected from surrounding buildings, asphalt, and other urban surfaces. They must also be tolerant to high daytime temperatures, typical of Atlanta’s summer months, and cold hardy in the winter months. Atlanta is located in USDA Plant Hardiness Zone 7b/8a. • Water wise. Urban tree wells are surrounded by impervious surfaces and thus, are highly susceptible to periods of drought. Suitable plants must be able to survive periods of low rainfall. • Pollution tolerant. Vehicle exhaust may leave deposits and pollutants on plant foliage, which can kill sensitive plants. • Encourage wildlife. Flowering plants attract insects such as butterflies while others provide food sources for birds and other wildlife. • Grown locally. Many of the plants listed are native to the Atlanta area, and all can be found at local nurseries. -

Officinalis Var. Biloba and Eucommia Ulmoides in Traditional Chinese Medicine

Two Thousand Years of Eating Bark: Magnolia officinalis var. biloba and Eucommia ulmoides in Traditional Chinese Medicine Todd Forrest With a sense of urgency inspired by the rapid disappearance of plant habitats, most researchers are focusing on tropical flora as the source of plant-based medicines. However, new medicines may also be developed from plants of the world’s temperate regions. While working in his garden in the spring of English yew (Taxus baccata), a species common 1763, English clergyman Edward Stone was in cultivation. Foxglove (Digitalis purpurea), positive he had found a cure for malaria. Tasting the source of digitoxin, had a long history as the bark of a willow (Salix alba), Stone noticed a folk medicine in England before 1775, when a bitter flavor similar to that of fever tree (Cin- William Withering found it to be an effective chona spp.), the Peruvian plant used to make cure for dropsy. Doctors now prescribe digitoxin quinine. He reported his discovery to the Royal as a treatment for congestive heart failure. Society in London, recommending that willow EGb 761, a compound extracted from the be tested as an inexpensive alternative to fever maidenhair tree (Gingko biloba), is another ex- tree. Although experiments revealed that wil- ample of a drug developed from a plant native to low bark could not cure malaria, it did reduce the North Temperate Zone. Used as an herbal some of the feverish symptoms of the disease. remedy in China for centuries, ginkgo extract is Based on these findings, Stone’s simple taste now packaged and marketed in the West as a test led to the development of a drug used every treatment for ailments ranging from short-term day around the world: willow bark was the first memory loss to impotence. -

Peter H. Griggs

STRATIGRAPHIC SIGNIFICANCE OF FOSSIL POLLEN AND SPORES OF THE CHUCKANUT FORMATION, NORTHWEST WASHINGTON Thosis far the Degree of. M. S. MICHIGAN STATE UNIVERSI'I’Y Peter H. Griggs 1965 ~-.. 'Wfi— wwWWL ‘1. .Illilllflu‘fllllf -Jnl.| IEI‘II‘I'IIIIVFI (II 'llllll‘lll.‘ I, l {III-III! I’lII 'II (III! III, [I , . III! [III [I I'll! (III. (I ABSTRACT STRATIGRAPHIC SIGNIFICANCE OF FOSSIL POLLEN AND SPORES OF THE CHUCKANUT FORMATION, NORTHWEST WASHINGTON by Peter H. Griggs The Chuckanut Formation, a series of strongly folded, terrestrial sandstones and shales, outcrops in northwestern Washington. The rocks have been previously assigned an age of Upper Cretaceous to lower Eocene based upon plant megafossils. The microfossil flora of the standard section along the east shore of Samish Bay was examined in order to determine the relationship of the Chuckanut to the Burrard (middle Eocene) of British Columbia. A zonation and envir- onmental interpretation of the standard section was desired for further refinement of the geological history of Tertiary rocks in the Pacific Northwest. Twenty—two samples, representing 9,H8u feet of section, were examined for palynomorphs. Data were collected for both relative frequency and stratigraphic analysis. Seventy— nine palynomorphs are described. The Samish Bay section is divided into three zones. The zonation is based on changes in the relative frequency f and the stratigraphic range of the palynomorphs. These ’ '_ ‘ V'II -7 r1 ' < P812631 ALL. '.,I I» ) I— (1 0'). OT changes were brought about by changing environmental and climatic conditions during the deposition of the rocks. An age of Paleocene to lower Eocene is assigned to the Samish Bay section. -

Kingdom Plantae

KIWIFRUIT Kingdom Plantae - Plants Subkingdom Tracheobionta - Vascular plants Superdivision Spermatophyta - Seed plants Division Magnoliophyta - Flowering plants Class Magnoliopsida - Dicotyledons Subclass Dilleniidae Order Theales Family Actinidiaceae - Chinese Gooseberry family Genus Actinidia Lindl. - Actinidia Species Actinidia Deliciosa - Kiwi Fruit Kiwi FACTS . Kiwi fruit gets its name from the kiwi bird, a flightless bird native to New Zealand. .Native to China where they called it the “macaque peach” . Contains just as much potassium as a banana. Useful for improving asthmatic conditions in children and preventing colon cancer. .Contain a protein dissolving enzyme called actinidin which can cause allergic reactions . Kiwi History Almost all kiwi fruit in commerce belong to a few cultivators of Actininidia deliciosa: Hayward, Chico, and Saanichton 12 which are almost all indistiguishable from each other First appeared in Southern China and is still considered its national fruit. Introduced to the western world in the beginning of the 20th century when missionaries from China brought them to New Zealand 1952 Kiwifruits were exported to New England 1958 the first kiwifruits were exported to California 1970 the first crop of kiwifruits were successfully harvested in California 1991 a new variety of golden kiwifruit was developed named Hort16A As of today the leading producers are Italy, New Zealand, Chile, France, Greece, Japan, and the USA Kiwi Cultivation Planted in a moderately sunny place and vines should be protected -

Vascular Plant and Vertebrate Inventory of Montezuma Castle National Monument Vascular Plant and Vertebrate Inventory of Montezuma Castle National Monument

Schmidt, Drost, Halvorson In Cooperation with the University of Arizona, School of Natural Resources Vascular Plant and Vertebrate Inventory of Montezuma Castle National Monument Vascular Plant and Vertebrate Inventory of Montezuma Castle National Monument Plant and Vertebrate Vascular U.S. Geological Survey Southwest Biological Science Center 2255 N. Gemini Drive Flagstaff, AZ 86001 Open-File Report 2006-1163 Southwest Biological Science Center Open-File Report 2006-1163 November 2006 U.S. Department of the Interior U.S. Geological Survey National Park Service In cooperation with the University of Arizona, School of Natural Resources Vascular Plant and Vertebrate Inventory of Montezuma Castle National Monument By Cecilia A. Schmidt, Charles A. Drost, and William L. Halvorson Open-File Report 2006-1163 November, 2006 USGS Southwest Biological Science Center Sonoran Desert Research Station University of Arizona U.S. Department of the Interior School of Natural Resources U.S. Geological Survey 125 Biological Sciences East National Park Service Tucson, Arizona 85721 U.S. Department of the Interior Dirk Kempthorne, Secretary U.S. Geological Survey Mark Myers, Director U.S. Geological Survey, Reston, Virginia: 2006 Note: This document contains information of a preliminary nature and was prepared primarily for internal use in the U.S. Geological Survey. This information is NOT intended for use in open literature prior to publication by the investigators named unless permission is obtained in writing from the investigators named and from the Station Leader. Suggested Citation Schmidt, C. A., C. A. Drost, and W. L. Halvorson 2006. Vascular Plant and Vertebrate Inventory of Montezuma Castle National Monument. USGS Open-File Report 2006-1163. -

ACTINIDIACEAE 1. ACTINIDIA Lindley, Nat. Syst. Bot., Ed. 2, 439

ACTINIDIACEAE 猕猴桃科 mi hou tao ke Li Jianqiang (李建强)1, Li Xinwei (李新伟)1; Djaja Djendoel Soejarto2 Trees, shrubs, or woody vines. Leaves alternate, simple, shortly or long petiolate, not stipulate. Flowers bisexual or unisexual or plants polygamous or functionally dioecious, usually fascicled, cymose, or paniculate. Sepals (2 or 3 or)5, imbricate, rarely valvate. Petals (4 or)5, sometimes more, imbricate. Stamens 10 to numerous, distinct or adnate to base of petals, hypogynous; anthers 2- celled, versatile, dehiscing by apical pores or longitudinally. Ovary superior, disk absent, locules and carpels 3–5 or more; placentation axile; ovules anatropous with a single integument, 10 or more per locule; styles as many as carpels, distinct or connate (then only one style), generally persistent. Fruit a berry or leathery capsule. Seeds not arillate, with usually large embryos and abundant endosperm. Three genera and ca. 357 species: Asia and the Americas; three genera (one endemic) and 66 species (52 endemic) in China. Economically, kiwifruit (Actinidia chinensis var. deliciosa) is an important fruit, which originated in central China and is especially common along the Yangtze River (well known as yang-tao). Now, it is widely cultivated throughout the world. For additional information see the paper by X. W. Li, J. Q. Li, and D. D. Soejarto (Acta Phytotax. Sin. 45: 633–660. 2007). Liang Chou-fen, Chen Yong-chang & Wang Yu-sheng. 1984. Actinidiaceae (excluding Sladenia). In: Feng Kuo-mei, ed., Fl. Reipubl. Popularis Sin. 49(2): 195–301, 309–334. 1a. Trees or shrubs; flowers bisexual or plants functionally dioecious .................................................................................. 3. Saurauia 1b. -

Origin and Beyond

EVOLUTION ORIGIN ANDBEYOND Gould, who alerted him to the fact the Galapagos finches ORIGIN AND BEYOND were distinct but closely related species. Darwin investigated ALFRED RUSSEL WALLACE (1823–1913) the breeding and artificial selection of domesticated animals, and learned about species, time, and the fossil record from despite the inspiration and wealth of data he had gathered during his years aboard the Alfred Russel Wallace was a school teacher and naturalist who gave up teaching the anatomist Richard Owen, who had worked on many of to earn his living as a professional collector of exotic plants and animals from beagle, darwin took many years to formulate his theory and ready it for publication – Darwin’s vertebrate specimens and, in 1842, had “invented” the tropics. He collected extensively in South America, and from 1854 in the so long, in fact, that he was almost beaten to publication. nevertheless, when it dinosaurs as a separate category of reptiles. islands of the Malay archipelago. From these experiences, Wallace realized By 1842, Darwin’s evolutionary ideas were sufficiently emerged, darwin’s work had a profound effect. that species exist in variant advanced for him to produce a 35-page sketch and, by forms and that changes in 1844, a 250-page synthesis, a copy of which he sent in 1847 the environment could lead During a long life, Charles After his five-year round the world voyage, Darwin arrived Darwin saw himself largely as a geologist, and published to the botanist, Joseph Dalton Hooker. This trusted friend to the loss of any ill-adapted Darwin wrote numerous back at the family home in Shrewsbury on 5 October 1836. -

VOLCANIC INFLUENCE OVER FLUVIAL SEDIMENTATION in the CRETACEOUS Mcdermott MEMBER, ANIMAS FORMATION, SOUTHWESTERN COLORADO

VOLCANIC INFLUENCE OVER FLUVIAL SEDIMENTATION IN THE CRETACEOUS McDERMOTT MEMBER, ANIMAS FORMATION, SOUTHWESTERN COLORADO Colleen O’Shea A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate College of Bowling Green State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF SCIENCE August: 2009 Committee: James Evans, advisor Kurt Panter, co-advisor John Farver ii Abstract James Evans, advisor Volcanic processes during and after an eruption can impact adjacent fluvial systems by high influx rates of volcaniclastic sediment, drainage disruption, formation and failure of natural dams, changes in channel geometry and changes in channel pattern. Depending on the magnitude and frequency of disruptive events, the fluvial system might “recover” over a period of years or might change to some other morphology. The goal of this study is to evaluate the preservation potential of volcanic features in the fluvial environment and assess fluvial system recovery in a probable ancient analog of a fluvial-volcanic system. The McDermott Member is the lower member of the Late Cretaceous - Tertiary Animas Formation in SW Colorado. Field studies were based on a southwest-northeast transect of six measured sections near Durango, Colorado. In the field, 13 lithofacies have been identified including various types of sandstones, conglomerates, and mudrocks interbedded with lahars, mildly reworked tuff, and primary pyroclastic units. Subsequent microfacies analysis suggests the lahar lithofacies can be subdivided into three types based on clast composition and matrix color, this might indicate different volcanic sources or sequential changes in the volcanic center. In addition, microfacies analysis of the primary pyroclastic units suggests both surge and block-and-ash types are present. -

John Day Fossil Beds National Monument

ISSUE VIII JANUARY 2007 NARG Newsletter North America Research Group Northwest Fossil Fest Recap Last August NARG held it's first annual Northwest Fossil Fest held at INSIDE THIS ISSUE the Rice Museum in Hillsboro Oregon. The goal of the Fest was to NW Fossil Fest Recap 1 promote, educate, showcase fossils Radiocarbon Dating Fund 3 from the Pacific NW, and to have John Day Fossil Beds fun, all of which was accomplished. National Monument 3 Taxonomy Report #6 5 The tagline for the Fest is “Inspire, Inquire, Interact” and nothing What is “Fossil Search and Rescue? inspires more than displaying some of the amazing fossils specimens that Oregon Fossils have been found in the Pacific NW. Plants of the Jurassic Period 7 Tami Smith making a batch of Trilobite Cookie Many guests where surprised at the Trilobite Morphology 8 wide range of life forms that once lived where we do today. Inquiry minds want to know and we had a top-notch line up of guest speakers such as Dr. Dr. Ellen Morris Bishop, Dr. Jeffrey A. Myers, and Dr. William. N. Orr. This was a great opportunity for guest not only to learn more about the paleontology and geology of Oregon but also to meet 3 of the leading professionals in these fields. More Trilobite Cookie making There were many ways to interact, from the fossil preparation area where demonstrations took place on tools and techniques used to prepare fossils, to fossil identification, and of course all the kids activities that NARG setup. The Screen for Shark Teeth was probably the biggest hits and over 1000 Bone Valley shark teeth where given away. -

Bgci's Plant Conservation Programme in China

SAFEGUARDING A NATION’S BOTANICAL HERITAGE – BGCI’S PLANT CONSERVATION PROGRAMME IN CHINA Images: Front cover: Rhododendron yunnanense , Jian Chuan, Yunnan province (Image: Joachim Gratzfeld) Inside front cover: Shibao, Jian Chuan, Yunnan province (Image: Joachim Gratzfeld) Title page: Davidia involucrata , Daxiangling Nature Reserve, Yingjing, Sichuan province (Image: Xiangying Wen) Inside back cover: Bretschneidera sinensis , Shimen National Forest Park, Guangdong province (Image: Xie Zuozhang) SAFEGUARDING A NATION’S BOTANICAL HERITAGE – BGCI’S PLANT CONSERVATION PROGRAMME IN CHINA Joachim Gratzfeld and Xiangying Wen June 2010 Botanic Gardens Conservation International One in every five people on the planet is a resident of China But China is not only the world’s most populous country – it is also a nation of superlatives when it comes to floral diversity: with more than 33,000 native, higher plant species, China is thought to be home to about 10% of our planet’s known vascular flora. This botanical treasure trove is under growing pressure from a complex chain of cause and effect of unprecedented magnitude: demographic, socio-economic and climatic changes, habitat conversion and loss, unsustainable use of native species and introduction of exotic ones, together with environmental contamination are rapidly transforming China’s ecosystems. There is a steady rise in the number of plant species that are on the verge of extinction. Great Wall, Badaling, Beijing (Image: Zhang Qingyuan) Botanic Gardens Conservation International (BGCI) therefore seeks to assist China in its endeavours to maintain and conserve the country’s extraordinary botanical heritage and the benefits that this biological diversity provides for human well-being. It is a challenging venture and represents one of BGCI’s core practical conservation programmes. -

Millerocaulis Tekelili Sp. Nov., a New Species of Osmundalean Fern from the Aptian Cerro Negro Formation (Antarctica) Ezequiel I

This article was downloaded by: [INASP - Pakistan ] On: 28 July 2011, At: 10:58 Publisher: Taylor & Francis Informa Ltd Registered in England and Wales Registered Number: 1072954 Registered office: Mortimer House, 37-41 Mortimer Street, London W1T 3JH, UK Alcheringa: An Australasian Journal of Palaeontology Publication details, including instructions for authors and subscription information: http://www.tandfonline.com/loi/talc20 Millerocaulis tekelili sp. nov., a new species of osmundalean fern from the Aptian Cerro Negro Formation (Antarctica) Ezequiel I. Vera Available online: 27 Jul 2011 To cite this article: Ezequiel I. Vera (2011): Millerocaulis tekelili sp. nov., a new species of osmundalean fern from the Aptian Cerro Negro Formation (Antarctica), Alcheringa: An Australasian Journal of Palaeontology, DOI:10.1080/03115518.2011.576541 To link to this article: http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/03115518.2011.576541 PLEASE SCROLL DOWN FOR ARTICLE Full terms and conditions of use: http://www.tandfonline.com/page/terms-and-conditions This article may be used for research, teaching and private study purposes. Any substantial or systematic reproduction, re-distribution, re-selling, loan, sub-licensing, systematic supply or distribution in any form to anyone is expressly forbidden. The publisher does not give any warranty express or implied or make any representation that the contents will be complete or accurate or up to date. The accuracy of any instructions, formulae and drug doses should be independently verified with primary sources. The publisher shall not be liable for any loss, actions, claims, proceedings, demand or costs or damages whatsoever or howsoever caused arising directly or indirectly in connection with or arising out of the use of this material. -

New Combinations in Actinidiaceae from China

New Combinations in Actinidiaceae from China Li Xin-Wei Herbarium (HIB), Wuhan Botanical Garden of Chinese Academy of Sciences, Wuhan 430074, People’s Republic of China; Graduate School of the Chinese Academy of Sciences, Beijing 100039, People’s Republic of China Li Jian-Qiang Herbarium (HIB), Wuhan Botanical Garden of Chinese Academy of Sciences, Wuhan 430074, People’s Republic of China. [email protected] (author for correspondence) Soejarto Djaja Djendoel College of Pharmacy, University of Illinois at Chicago, 833 S. Wood Street, Chicago, Illinois 60612, U.S.A. ABSTRACT . During the revision of Actinidiaceae for The taxonomy of Saurauia Willdenow is much less the Flora of China, two new combinations are confusing than that of Actinidia, although the trichome proposed, Actinidia fulvicoma var. cinerascens (C. F. and other characters exhibit considerable variation; Liang) J. Q. Li & D. D. Soejarto and Saurauia we recognize 13 species from China. polyneura var. paucinervis (C. F. Liang & Y. S. Wang) J. Q. Li & D. D. Soejarto. 1. Actinidia fulvicoma Hance, J. Bot. 23: 321. Key words: Actinidia, China, Guangxi, Saurauia, 1885. TYPE: China. Guangdong: Luo-Fu-Shan, Xizang. May 1883, B. C. Henry s.n. (holotype, K). 1a. Actinidia fulvicoma var. cinerascens (C. F. In the first comprehensive revision of Actinidia Liang) J. Q. Li & D. D. Soejarto, comb. nov. Lindley, Dunn recognized 24 species in four sections, Basionym: Actinidia cinerascens C. F. Liang, Fl. i.e., sections Ampulliferae Dunn, Leiocarpae Dunn, Reipubl. Popularis Sin. 49(2): 252–254, 320– Maculatae Dunn, and Vestitae Dunn (Dunn, 1911). 321. 1984. TYPE: China. Guangdong: Luofu Later, H.