Documew Resume

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

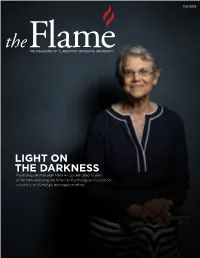

Light on the Darkness

Fall 2016 the FlameTHE MAGAZINE OF CLAREMONT GRADUATE UNIVERSITY LIGHT ON THE DARKNESS Psychology alumna Jean Maria Arrigo dedicated 10 years of her life to exposing the American Psychological Association’s secret ties to US military interrogation efforts MAKE A GIFT TO THE ANNUAL FUND TODAY the Flame Claremont Graduate University THE MAGAZINE OF CLAREMONT GRADUATE UNIVERSITY fellowships play an important role Fall 2016 The Flame is published by in ensuring our students reach their Claremont Graduate University’s Office of Marketing and Communications educational goals, and annual giving 165 East 10th Street Claremont, CA 91711 from our alumni and friends is a ©2016 Claremont Graduate University major contributor. Here are some of VICE PRESIDENT FOR ADVANCEMENT our students who have benefitted Ernie Iseminger ASSOCIATE VICE PRESIDENT, STRATEGIC COMMUNICATIONS from the CGU Annual Fund. Max Benavidez EXECUTIVE DIRECTOR, MARKETING AND COMMUNICATIONS Andrea Gutierrez “ I am truly grateful for the support that EXECUTIVE DIRECTOR, ADVANCEMENT COMMUNICATIONS CGU has given me. This fellowship has Nicholas Owchar provided me with the ability to focus MANAGING EDITOR on developing my career.” Roberto C. Hernandez Irene Wang, MBA and MA DESIGNER Shari Fournier-O’Leary in Management DIRECTOR, DESIGN SERVICES Gina Pirtle I received fellowship offers from other ASSISTANT DIRECTOR, INTEGRATED MARKETING “ Alfie Christiansen schools. But the amount of my fellowship ASSISTANT DIRECTOR, DIGITAL COMMUNICATIONS from CGU was the biggest one, and Sheila Lefor I think that is one of my proudest DISTRIBUTION MANAGER moments.” Mandy Bennett Akihiro Toyoda, MBA PHOTOGRAPHERS Carlos Puma John Valenzuela If I didn’t have the fellowship, there is William Vasta “ Tom Zasadzinski no way I would have been able to study for a PhD. -

The Fruits of Our Labors!

ISSUED 6 TIMES PER YEAR JANUARY & FEBRUARY 2010 VOLUME 38 ~ ISSUE 6 The WYSU & Mill Creek MetroParks Partnership: The Fruits of our Labors! During the past three WYSU To view images of the tree plant- on-air fund drives, members who ing site, as well as some examples contributed to WYSU at the $120 of the kinds of trees planted, please ‘Supporter’ level could choose to have visit this website: http://tinyurl.com/ a tree planted in their honor in Mill WYSUMetroParktrees Creek MetroParks as their thank-you So far, by virtue of the WYSU gift. community partnership with Mill The first group of such tree plant- Creek MetroParks and our special ings took place in autumn 2009 at tree planting premium, WYSU lis- the Mill Creek Preserve, located on teners have been responsible for the Western Reserve and Tippecanoe planting of 182 trees in Mill Creek Roads. The types of trees planted for MetroParks! this initial planting included: black Thank you for supporting walnut, serviceberry, black tupelo, WYSU—and our local environment. shagbark hickory, black oak, white pine, sweet birch, black cherry, crabapple, red maple, sugar maple, swamp white oak, and persimmon. These species were chosen because of their ability to provide wildlife habitat and supply food in the form of fruit, nuts, and berries. WYSU would like to thank everyone who elected to “go green” with their premium selection, thereby helping us preserve one of the last wild places in Mahoning County. Yours is a gift that will last a lifetime! WYSU’s 12th note 88.5 MHz, 90.1 MHz, 97.5 MHz Program Listings 2010 January & February MON TUES WED THURS FRI SAT SUN Mid. -

Wolf Trap Presents a Prairie Home Companion with Garrison Keillor and Under the Streetlamp and Gentleman’S Rule

May 9, 2014 Contact: Camille Cintrón, Manager, Public Relations 703.255.4096 or [email protected] Wolf Trap Presents A Prairie Home Companion with Garrison Keillor and Under the Streetlamp and Gentleman’s Rule All Shows at the Filene Center at Wolf Trap National Park for the Performing Arts 1551 Trap Road, Vienna, VA 22182 A Prairie Home Companion with Garrison Keillor and Special Guests: Heather Masse & Vince Giordano and the Nighthawks In association with Minnesota Public Radio & WAMU 88.5 FM Friday, May 23, 2014 at 8 pm Saturday, May 24, 2014 at 5:45 pm $25-$65 A Prairie Home Companion returns to Wolf Trap with the nation’s favorite radio host, Garrison Keillor. The variety show, which airs live every Saturday night, features an assortment of musical guests, comedy sketches, and Garrison Keillor’s signature monologue “The News from Lake Wobegon,” for which Keillor won a Grammy Award in 1988. Keillor’s other awards include a National Humanities Medal from the National Endowment for the Humanities and a Medal for Spoken Language from the American Academy of Arts and Letters. A Prairie Home Companion has grown from humble beginnings—its premiere show in 1974 had an audience of only 12 people, but today, it is broadcast on more than 600 public radio stations and has an audience of more than 4 million listeners every week. Video: Garrison Keillor – “Ten Things to Know Before You Move to Duluth” Grammy Award-winning Vince Giordano and the Nighthawks are dedicated to keeping big band music alive and swinging in the 21st century. -

The Book Thief

Ryde Library Service Community Book Club Collection Becoming By Michelle Obama First published in 2018 Genre & subject Biography Michelle Obama President’s spouses Synopsis An intimate, powerful, and inspiring memoir by the former First Lady of the United States In a life filled with meaning and accomplishment, Michelle Obama has emerged as one of the most iconic and compelling women of our era. As First Lady of the United States of America- the first African-American to serve in that role-she helped create the most welcoming and inclusive White House in history, while also establishing herself as a powerful advocate for women and girls in the U.S. and around the world, dramatically changing the ways that families pursue healthier and more active lives, and standing with her husband as he led America through some of its most harrowing moments. Along the way, she showed us a few dance moves, crushed Carpool Karaoke, and raised two down-to-earth daughters under an unforgiving media glare. In her memoir, a work of deep reflection and mesmerizing storytelling, Michelle Obama invites readers into her world, chronicling the experiences that have shaped her-from her childhood on the South Side of Chicago to her years as an executive balancing the demands of motherhood and work, to her time spent at the world's most famous address. With unerring honesty and lively wit, she describes her triumphs and her disappointments, both public and private, telling her full story as she has lived it-in her own words and on her own terms. Warm, wise, and revelatory, Becoming is the deeply personal reckoning of a woman of soul and substance who has steadily defied expectations-and whose story inspires us to do the same. -

A Prairie Home Companion”: First Broadcast (July 6, 1974) Added to the National Registry: 2003 Essay by Chuck Howell (Guest Post)*

“A Prairie Home Companion”: First Broadcast (July 6, 1974) Added to the National Registry: 2003 Essay by Chuck Howell (guest post)* Garrison Keillor “Well, it's been a quiet week in Lake Wobegon, Minnesota, my hometown, out on the edge of the prairie.” On July 6, 1974, before a crowd of maybe a dozen people (certainly less than 20), a live radio variety program went on the air from the campus of Macalester College in St. Paul, MN. It was called “A Prairie Home Companion,” a name which at once evoked a sense of place and a time now past--recalling the “Little House on the Prairie” books, the once popular magazine “The Ladies Home Companion” or “The Prairie Farmer,” the oldest agricultural publication in America (founded 1841). The “Prairie Farmer” later bought WLS radio in Chicago from Sears, Roebuck & Co. and gave its name to the powerful clear channel station, which blanketed the middle third of the country from 1928 until its sale in 1959. The creator and host of the program, Garrison Keillor, later confided that he had no nostalgic intent, but took the name from “The Prairie Home Cemetery” in Moorhead, MN. His explanation is both self-effacing and humorous, much like the program he went on to host, with some sabbaticals and detours, for the next 42 years. Origins Gary Edward “Garrison” Keillor was born in Anoka, MN on August 7, 1942 and raised in nearby Brooklyn Park. His family were not (contrary to popular opinion) Lutherans, instead belonging to a strict fundamentalist religious sect known as the Plymouth Brethren. -

So Long, Lake Wobegon? Using Teacher Evaluation to Raise Teacher Quality

FLICKR.COM/ O LD WOMAN SHOE WOMAN LD So Long, Lake Wobegon? Using Teacher Evaluation to Raise Teacher Quality Morgaen L. Donaldson June 2009 WWW.AMERICANPROGRESS.ORG So Long, Lake Wobegon? Using Teacher Evaluation to Raise Teacher Quality Morgaen L. Donaldson June 2009 Executive summary In recent months, ideas about how to improve teacher evaluation have gained prominence nationwide. In April, 2009, Secretary of Education Arne Duncan proposed that districts report the percentage of teachers rated in each evaluation performance category. Michelle Rhee, chancellor of the Washington, D.C. public schools, has proposed evaluating teach- ers largely on the basis of their students’ performance. Georgia and Idaho have launched major efforts to reform teacher evaluation at the state level. Meanwhile, researchers have noted that a well-designed and implemented teacher evaluation system may be the most effective way to raise student achievement.1 And teacher evaluation reaches schools and districts in every corner of the country, positioning it to affect important aspects of school- ing such as teacher collaboration and school culture, in addition to student achievement. Historically, teacher evaluation has not substantially improved instruction or expanded student learning. The last major effort to reform teacher evaluation, in the 1980s, petered out after much fanfare. Today there are reasons to believe that conditions are right for substantive improvements to evaluation. Important advances in our knowledge of effective teaching practices, shifts in the composition of the educator workforce, and changes in the context of public education provide a key opportunity for policymakers to tighten the link between teacher evaluation and student learning. -

DOLLAR GENERAL 100 Angelfish Ave Avon, MN (St

NET LEASE INVESTMENT OFFERING DOLLAR GENERAL 100 Angelfish Ave Avon, MN (St. Cloud MSA) TABLE OF CONTENTS TABLE OF CONTENTS I. Executive Profile II. Location Overview III. Market & Tenant Overview Executive Summary Aerial Demographic Report Investment Highlights Site Plan Market Overview Property Overview Map Tenant Overview NET LEASE INVESTMENT OFFERING DISCLAIMER STATEMENT DISCLAIMER The information contained in the following Offering Memorandum is proprietary and strictly confidential. STATEMENT: It is intended to be reviewed only by the party receiving it from The Boulder Group and should not be made available to any other person or entity without the written consent of The Boulder Group. This Offering Memorandum has been prepared to provide summary, unverified information to prospective purchasers, and to establish only a preliminary level of interest in the subject property. The information contained herein is not a substitute for a thorough due diligence investigation. The Boulder Group has not made any investigation, and makes no warranty or representation. The information contained in this Offering Memorandum has been obtained from sources we believe to be reliable; however, The Boulder Group has not verified, and will not verify, any of the information contained herein, nor has The Boulder Group conducted any investigation regarding these matters and makes no warranty or representation whatsoever regarding the accuracy or completeness of the information provided. All potential buyers must take appropriate measures to verify all of the information set forth herein. NET LEASE INVESTMENT OFFERING EXECUTIVE SUMMARY EXECUTIVE The Boulder Group is pleased to exclusively market for sale a single tenant net leased Dollar General property SUMMARY: located within the St. -

Augustana Book Club History and Selections 2001-Present from the Church Bulletins in Oct

Augustana Book Club History and Selections 2001-present From the church bulletins in Oct. 2001: "Book Club coming soon. Are YOU interested?" Meeting set for 7 pm Oct. 23 in the church library "The first meeting will be a time to plan our reading and meeting places." Contact Joanne Mecklem or Amy Plumb Book Author 2001 Oct. FIRST MEETING Nov. The Samurai's Garden Gail Tsukiyama Dec. Martin Luther's Christmas Book Martin Luther 2002 Jan. Dakota Kathleen Norris Feb. Reservation Blues Sherman Alexie March The Bridge Doug Marlett April Teaching a Stone to Talk Annie Dillard May NO MEETING June To Know a Woman Amos Oz July NO MEETING Aug. "Book Potluck"--Share a summertime read Sept. The Poisonwood Bible Barbara Kingsolver Oct. Bel Canto Ann Patchett Nov. The Lovely Bones Alice Sebold Father Melancholy's Daughter @ Cooke Dec. Gail Godwin First book club hosted at a home and not church library 2003 A Lesson Before Dying @ Wackers (Everybody Reads) Jan. We have read each MultCo Library Everybody Reads selection since Ernest Gaines the program began in Winter 2003 A Fine Balance @ Van Winkles Feb. In the bulletin: "Over the next months the group will be meeting in homes Rohinton Mistry and enjoying potluck with a book-inspired menu." March Bless Me, Ultima @ Kindschuhs Rudolfo Anaya Choice of books @ Ranks: The Clash of Civilizations & the Remaking of the World Order Samuel Huntington Guns, Germs, and Steel: The Fate of Human Societies Jared Diamond April The Wealth of Nations David Landers Culture Matters: How Values Shape Human Progress ed.Lawrence Harrison,Samuel Huntington Islam: An Introduction for Christians ed.Paul V. -

Deepening Discipleship Table South Carolina Synod Assembly 2021

BULLETIN OF REPORTS CHAPTER FOUR - 1 Deepening Discipleship Table South Carolina Synod Assembly 2021 Dear Partners in the Gospel, I have taken great delight in Garrison Keillor’s book entitled “Life among the Lutherans”. It is a wonderful walk through “his hometown, Lake Wobegon” in Minnesota, which in actuality is a collection of his talk’s on his radio show on public radio, A Prairie Home Companion. As we of the South Carolina Synod discern our calling to discipleship for our Lord Christ Jesus, Keillor shares some apt thoughts. They can make us blush and smile but also empower us to deepen our discipleship as we share the Gospel. He writes on page 3: “The people who occupy the pews of Lake Wobegon Lutheran on Sunday are ordinary people, doing their best to be good and walk straight in a world that seems to reward the crooked and mock the righteous. They gather and give alms to the poor; they sing, "Lift every voice and sing till earth and heaven ring," so that tears come to your eyes; and they pray to God, "Create in me a clean heart, 0 God, and renew a right spirit within me. Cast me not away from thy presence and take not thy Holy Spirit from me. Restore unto me the joy of thy salvation…" And then they go home and put on their work clothes and tend their flowerbeds and groom their lawns. While they do their best to love each other, they also watch each other very closely, there is gossip, on occasion. -

What Happened Hillary Rodham Clinton This Reading Group Guide

What Happened Hillary Rodham Clinton This reading group guide for What Happened includes an introduction, discussion questions, and ideas for enhancing your book club. The suggested questions are intended to help your reading group find new and interesting angles and topics for your discussion. We hope that these ideas will enrich your conversation and increase your enjoyment of the book. Introduction Hillary Rodham Clinton is the first woman in US history to become the presidential nominee of a major political party. She served as the 67th Secretary of State—from January 21, 2009, until February 1, 2013 —after nearly four decades in public service advocating on behalf of children and families as an attorney, First Lady, and Senator. She is a wife, mother, and grandmother. In What Happened Hillary Clinton reveals, for the first time, what she was thinking and feeling during one of the most controversial and unpredictable presidential elections in history. Now free from the constraints of running, Hillary takes you inside the intense personal experience of becoming the first woman nominated for president by a major party in an election marked by rage, sexism, exhilarating highs and infuriating lows, stranger-than-fiction twists, Russian interference, and an opponent who broke all the rules. This is her most personal memoir yet. Topics & Questions for Discussion 1. In the Introduction to What Happened, Hillary Clinton begins with this statement: “In the past, for reasons I try to explain, I’ve often felt I had to be careful in public, like I was up on a wire without a net. -

Lake Wobegon Days Loretta Wasserman Grand Valley State University

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Scholarworks@GVSU Grand Valley Review Volume 1 | Issue 1 Article 17 1-1-1986 Lake Wobegon Days Loretta Wasserman Grand Valley State University Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarworks.gvsu.edu/gvr Recommended Citation Wasserman, Loretta (1986) "Lake Wobegon Days," Grand Valley Review: Vol. 1: Iss. 1, Article 17. Available at: http://scholarworks.gvsu.edu/gvr/vol1/iss1/17 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by ScholarWorks@GVSU. It has been accepted for inclusion in Grand Valley Review by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks@GVSU. For more information, please contact [email protected]. 62 IDRETTA WASSERMAN Early chapte it New Albion Lake Wobegon Days man Catholics and happenin~ Lake Wobegon Days by Garrison Keillor, Viking Press, $17.95. tions - the ol1 and the preser Nineteen eighty-five saw the publication of an odd book of humor that was an of free associa astonishing success - astonishing at least to those of us who thought our fondness Keillor clear for Garrison Keillor's radio stories about Lake Wobegon, Minnesota ("the little town transcendenta that time forgot"), marked us as members of a smallish group: not a cult (fanaticism of Minnesota. of any kind not being a Wobegon trait), but still a distinct spectrum. Not so, apparently. Alcott is the s At year's end was at the very top of the charts, where it stayed Lake Wobegon Days Rain Dance a1 for several weeks, and had sold well over a million copies. -

The Rhetoric of Political Comedy: a Tragedy?

International Journal of Communication 7 (2013), 338–370 1932–8036/20130005 The Rhetoric of Political Comedy: A Tragedy? RODERICK P. HART University of Texas at Austin See the companion work to this article “Paradying the Protest Paradigm? How Political Satire Complicates the Empirical Study of Traditional News Frames” by Dannagal G. Young in this Special Section This essay wades into the controversy surrounding Jon Stewart’s The Daily Show. Although some scholars have pointed up its constructive impact, others find it a harbinger of cynicism, superficiality, and excessive partisanship. This study offers a content analysis of Daily Show transcripts focused on social protest, and of a philosophical interview with Jon Stewart conducted by Rolling Stone magazine. Results show Stewart avoiding traditional forms of ideology, featuring desultory politics, stressing personal over group interactions, and embracing several dialectical choices— ideas vs. behavior, politicians vs. the electorate, and comedians vs. reporters. When the data are viewed as a whole, Stewart’s all-seeing, all-knowing rhetoric is identified as problematic, as is his lonely model of public life. Both make it hard to hold out hope for political solutions and that seems especially true for young people. While none of the foregoing claims can be considered definitive, they present new questions about The Daily Show’s impact on our life and times. Jon Stewart, impresario of The Daily Show, has surely caught the attention of the academic community. Amber Day (2011) describes Stewart as “the everyman’s stand-in,” one who “is able to act as the viewer’s surrogate,” thereby giving the American people “vicarious pleasure in hearing [their] own opinions aired on national television” (p.