Transcript of the Spoken Word, Rather Than Written Prose

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Culture Jamming

Acknowledgements First and foremost, I would like to thank Vincent de Jong for introducing me to the intricacy of the easyCity action, and for taking the time to answer my questions along my exploration of the case. I also want to thank Robin van t’ Haar for his surprising, and unique, contribution to my investigations of the easyCity action. Rozalinda Borcila, the insights you have shared with me have been a crucial reminder of my own privilieged position – your reflections, I hope, also became a marker in what I have written. Also, I would like to thank others that somehow made my fieldwork possible, and influenced my ‘learning’ of activism and culture jamming. Of these I would especially like to thank Nina Haukeland for introducing me to the politics of activism, Kirsti Hyldmo for reminding me of the realities of exploitation, Åse Brandvold for a skilled introduction to the thoughts and tools of culture jamming, and Maria Astrup for showing me the pleasures and powers of aesthetics. Also, I would like to thank the Norwegian Adbusters Network, and the editorial groups of Vreng. To my main advisor Professor Kristian Stokke, I would like to thank you for the excellent support you have given me throughout my master studies. Your insights have been of grate value, and I cannot thank you enough for continually challenging me. Also, the feedback from Olve Krange, my second advisor, was crucial at the early stage of developing the thesis, to defining its object of inquiry, and finally when writing my conclusion. I would also like to express my appreciation to Professor Oddrun Sæther for an excellent introduction to the field of cultural studies, to Professor Matt Sparke at the University of Washington for demonstrating the intriguing complexities of political geography, and to PhD candidate Stephen Young, for proof reading and fruitful inputs at the final stage of writing. -

Scoville, Curtailing the Cudgel of "Coordination"

Curtailing the Cudgel of “Coordination” by Curing Confusion: How States Can Fix What the Feds Got Wrong on Campaign Finance GEORGE S. SCOVILLE III* I. INTRODUCTION.......................................................................... 465 II. FEDERAL COORDINATION DOCTRINE ........................................ 475 A. Establishing the Regime .............................................. 475 1. The Federal Election Campaign Act and Buckley’s Curious Dual Anti-Corruption Rationale ................ 475 2. The Bipartisan Campaign Reform Act, the FEC’s Coordination Regulations, and Recent Cases .......... 482 B. Hypos Showing Ambiguity in Federal Conduct Standards ...................................................... 487 1. The Coffee Shop Hypo........................................... 487 2. The Photo Hypo ..................................................... 488 3. The Polling Hypo ................................................... 489 * Editor-in-Chief, Volume 48 The University of Memphis Law Review; Candidate for Juris Doctor and Business Law Certificate, 2018, The University of Memphis Cecil C. Humphreys School of Law; Master of Public Policy, 2011, American University School of Public Affairs. For Emily, whose steadfast love has been the sine qua non of my studies. Thank you to countless family, friends, colleagues, and mentors for boundless guidance and support, especially Capital University Josiah H. Blackmore II/Shirley M. Nault Professor of Law Bradley A. Smith, Cecil C. Humphreys School of Law Professors Steven J. Mulroy and John M. Newman, and my colleagues, past and present, at The University of Memphis Law Review, especially Callie Tran, Liz Stagich, and Connor Dugosh. “If I have seen further, it is by standing on ye shoulders of giants.” Letter from Isaac Newton to Robert Hooke (Feb. 5, 1675) (on file with the Historical Society of Pennsylvania), http://digitallibrary.hsp.org/index.php/Detail/Object/Show/object_id/9285. 463 464 The University of Memphis Law Review Vol. -

Re:Imagining Change

WHERE IMAGINATION BUILDS POWER RE:IMAGINING CHANGE How to use story-based strategy to win campaigns, build movements, and change the world by Patrick Reinsborough & Doyle Canning 1ST EDITION Advance Praise for Re:Imagining Change “Re:Imagining Change is a one-of-a-kind essential resource for everyone who is thinking big, challenging the powers-that-be and working hard to make a better world from the ground up. is innovative book provides the tools, analysis, and inspiration to help activists everywhere be more effective, creative and strategic. is handbook is like rocket fuel for your social change imagination.” ~Antonia Juhasz, author of e Tyranny of Oil: e World’s Most Powerful Industry and What We Must Do To Stop It and e Bush Agenda: Invading the World, One Economy at a Time “We are surrounded and shaped by stories every day—sometimes for bet- ter, sometimes for worse. But what Doyle Canning and Patrick Reinsbor- ough point out is a beautiful and powerful truth: that we are all storytellers too. Armed with the right narrative tools, activists can not only open the world’s eyes to injustice, but feed the desire for a better world. Re:Imagining Change is a powerful weapon for a more democratic, creative and hopeful future.” ~Raj Patel, author of Stuffed & Starved and e Value of Nothing: How to Reshape Market Society and Redefine Democracy “Yo Organizers! Stop what you are doing for a couple hours and soak up this book! We know the importance of smart “issue framing.” But Re:Imagining Change will move our organizing further as we connect to the powerful narrative stories and memes of our culture.” ~ Chuck Collins, Institute for Policy Studies, author of e Economic Meltdown Funnies and other books on economic inequality “Politics is as much about who controls meanings as it is about who holds public office and sits in office suites. -

The Weed Whisperer: a Doonesbury Book Free

FREE THE WEED WHISPERER: A DOONESBURY BOOK PDF G B Trudeau | 176 pages | 19 Nov 2015 | Andrews McMeel Publishing | 9781449472245 | English | Kansas City, United States The Weed Whisperer - Andrews McMeel Publishing And through it all, Doonesbury has always been honest, entertaining, and way, way cool. He glorifies drugs. Two centuries after the Founding Fathers signed off on happiness, Zonker Harris and nephew Zipper pull up stakes and head west in hot pursuit. The The Weed Whisperer: A Doonesbury Book Meanwhile, eternally blocked writer Jeff Redfern struggles to keep the Red Rascal legend-in-his-own-mind franchise alive, while aging music icon Jimmy T. For the record, Trudeau always inhaled back in the day. This website contains affiliate links. Overview Syndication Website. Licensing Licensing Website. About the Author. Trudeau has been drawing his Pulitzer Prize-winning comic strip for more than forty years. In addition to cartooning, Trudeau has worked in theater, film, and The Weed Whisperer: A Doonesbury Book. They have three grown children. Mel's Story G. Welcome to the Nerd Farm! Talk to the Hand G. Red Rascal's War G. Signature Wound G. Tee Time in Berzerkistan G. My Shorts R Bunching. Heckuva Job, Bushie! The War Within G. Dude G. The Long Road Home G. Got War? Peace Out, Dawg! The Revolt of the English Majors G. Action Figure! Duke Whatever It Takes G. Buck Wild Doonesbury G. The Bundled Doonesbury G. Planet Doonesbury G. Doonesbury Nation G. The Portable Doonesbury G. Quality Time on Highway 1 G. I'd Go with the Helmet, Ray G. -

March 2013 Sunday Morning Talk Show Data

March 2013 Sunday Morning Talk Show Data March 3, 2013 25 men and 10 women NBC's Meet the Press with David Gregory: 5 men and 2 women Speaker of the House John Boehner (M) Gene Sperling (M) Rep. Raul Labrador (M) Kathleen Parker (F) Joy Reid (F) Chuck Todd (M) Tom Brokaw (M) CBS's Face the Nation with Bob Schieffer: 7 men and 1 woman Sen. Lindsey Graham (M) Sen. John McCain (M) Sen. Majority Whip Dick Durbin (M) Cardinal Timothy Dolan (M) Bob Woodward (M) David Sanger (M) Rana Foroohar (F) John Dickerson (M) ABC's This Week with George Stephanopoulos: 4 men and 3 women Gene Sperling (M) Sen. Kelly Ayotte (F) James Carville (M) Matthew Dowd (M) Paul Gigot (M) Mayor Mia Love (F) Cokie Roberts (F) CNN's State of the Union with Candy Crowley: 6 men and 1 woman Sen. Minority Leader Mitch McConnell (M) Gene Sperling (M) Rep. Steve Israel (M) Rep. Greg Walden (M) Mark Zandi (M) Stephen Moore (M) Susan Page (F) Fox News' Fox News Sunday with Chris Wallace: 3 men and 3 women Fmr. Gov. Mitt Romney (M) Ann Romney (F) Bill Kristol (M) Kirsten Powers (F) Fmr. Sen. Scott Brown (F) Charles Lane (M) March 10, 2013 25 men and 13 women NBC's Meet the Press with David Gregory: 6 men and 3 women Sen. Tim Kaine (M) Sen. Tom Coburn (M) Rep. Tulsi Gabbard (F) Rep. Cory Garnder (M) Joe Scarborough (M) Dee Dee Myers (F) Rep. Marsha Blackburn (F) Steve Schmidt (M) Ruth Marcus (F) Fmr. -

Taking Our Country Back: the New Left, Deaniacs, and the Production of Contemporary American Politics

Taking Our Country Back: The New Left, Deaniacs, and the Production of Contemporary American Politics Daniel Kreiss, Ph.D. Candidate Department of Communication, Stanford University [email protected] ***The following is a draft, please do not cite or distribute without speaking to the author.*** Paper presented at Politics: Web 2.0: An International Conference, hosted by the New Political Communication Unit at Royal Holloway, University of London, April 17-18, 2008. Abstract This paper examines the evolution of ideas about participatory democracy and expressive politics and their articulation alongside new media with an eye towards revealing the historical antecedents of the 2003-2004 Howard Dean campaign. Through a comprehensive survey of documents produced by social movements, media artists, computer hobbyists, and the Dean campaign this paper presents the uptake of participatory theory and performative politics through networked tools and demonstrates how 1960s social and technical movements shaped the cultural meaning and practices of the Dean campaign. As the Internet and computing technology more generally became a repository for hopes of a renewal of democracy, the campaign was able to bring together a network of actors whose professional careers were located in the fields of politics and technology, and who in turn spawned a number of influential consulting firms and conferences which served as the mechanisms of diffusion for a particular form of electoral politics across the political field. Introduction Outside of a $500-a-plate fundraiser in 1968 in San Francisco for Democratic presidential candidate Robert Kennedy, Jerry Rubin and a group of self-described “freaks” greeted the entering guests with shouts of “Have a free bologna sandwich! Why pay $500 for bologna inside when you can get free bologna right here?” (Rubin 1970, 138). -

Arbiter, August 28 Students of Boise State University

Boise State University ScholarWorks Student Newspapers (UP 4.15) University Documents 8-28-2003 Arbiter, August 28 Students of Boise State University Although this file was scanned from the highest-quality microfilm held by Boise State University, it reveals the limitations of the source microfilm. It is possible to perform a text search of much of this material; however, there are sections where the source microfilm was too faint or unreadable to allow for text scanning. For assistance with this collection of student newspapers, please contact Special Collections and Archives at [email protected]. SIN C E 9 J J BOISE STATE'S I N D E_P EN DEN T STU DEN T NEW SPA PER Ii CELEBRATING i THURSDAY 70 YEARS AUGUST 28, 2003 Sports- 6 Win free textbooks - page 3 A&E-9 Bronco volleyball Q&A with David Mikell Starlight Mints: / season preview -page6 fresh new sound FIRST COPY FREE WWW.,ARB1TERONLINE.GOM VOLUME 16 ISSUE 4 Dean sidesteps ASHe'ROFT VISIT SPURS LIVELY usual haunts for nationwide PROTEST IN BOISE campaigning BY RONALD BROWNSTEIN Los An~eles Times Los Angeles Times-Washington Post News Service AUSTIN, Texas From suburban Washington, D.C., to downtown Seattle and even President Bush's home state, Howard Dean has sent a message in the past three days to his Democratic presidential rivals with ail imposing display of nationwide organizational strength. Since Saturday night, Dean has crisscrossed the United States on a four-day, eight-state, lO-city "Sleepless Summer Tour" that reached Texas on Monday and ended Tuesday with a late-night rally in New York. -

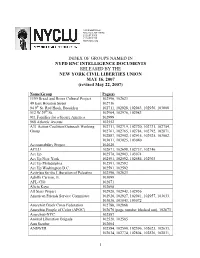

Index of Political Groups Mentioned in the Intelligence Documents

125 Broad Street New York, NY 10004 212.607.3300 212.607.3318 www.nyclu.org INDEX OF GROUPS NAMED IN NYPD RNC INTELLIGENCE DOCUMENTS RELEASED BY THE NEW YORK CIVIL LIBERTIES UNION MAY 16, 2007 (revised May 22, 2007) Name/Group Page(s) 1199 Bread and Roses Cultural Project 102596, 102623 49 East Houston Street 102716 94 9th St. Red Hook, Brooklyn 102711, 102928, 102943, 102956, 103008 512 W 29th St. 102964, 102976, 102983 911 Families for a Secure America 102999 968 Atlantic Avenue 102552 A31 Action Coalition/Outreach Working 102711, 102719, 102720, 102731, 102754, Group 102761, 102765, 102784, 102792, 102871, 102887, 102902, 102915, 102925, 103002, 103011, 103025, 103040 Accountability Project 102620 ACLU 102671, 102698, 102737, 102746 Act Up 102578, 102903, 103074 Act Up New York 102591, 102592, 102684, 102903 Act Up Philadelphia 102591, 102592 Act Up Washington D.C. 102591, 102592 Activists for the Liberation of Palestine 102596, 102623 Adolfo Carrion, Jr. 103099 AFL-CIO 102671 Alicia Keys 102698 All Stars Project 102928, 102943, 102956 American Friends Service Committee 102920, 102927, 102941, 102957, 103033, 103036, 103043, 103072 Anarchist Black Cross Federation 102788, 102868 Anarchist People of Color (APOC) 102670 (page number blacked out), 102673 Anarchist-NYC 102587 Animal Liberation Brigade 102520, 102585 Ann Stauber 102604 ANSWER 102584, 102590, 102596, 102623, 102633, 102634, 102774, 102804, 102826, 102831, 1 102843, 102884, 102900, 102906, 102916, 102919, 102926, 102940, 102952, 102959, 103068, 103076, 103092, 103096 Anthony -

Dead Kennedys and the Yippie-Punk Continuum I Michael Stewart Foley

Political Pie-Throwing: Dead Kennedys and the Yippie-Punk Continuum i Michael Stewart Foley To cite this version: Michael Stewart Foley. Political Pie-Throwing: Dead Kennedys and the Yippie-Punk Continuum i. Sonic Politics: Music and Social Movements in the Americas, 2019, 1138389390. hal-01999010 HAL Id: hal-01999010 https://hal.univ-grenoble-alpes.fr/hal-01999010 Submitted on 30 Jan 2019 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. Political Pie-Throwing: Dead Kennedys and the Yippie-Punk Continuumi MICHAEL STEWART FOLEY By the time Dead Kennedys released their first LP, Fresh Fruit for Rotting Vegetables, in 1980, the band had established itself as the leading American political punk band, hailing from a city that seemed to specialize in political art. In many ways, the band and its music represented the culmination of nearly three years of subcultural political struggle on a host of issues facing not only young people in San Francisco but American youth everywhere – enough that, to this day, many of the city’s punk veterans refer to their experience in the “movement.” Political historians of the United States in the 1970s and 1980s have mostly ignored punk, but this essay examines Dead Kennedys’ early career as a way to illuminate the political experience of one segment of American youth in the late 1970s. -

DOC 501 Prairie Fire Organizing Committee/John Brown Book Club

DOC 501 Prairie Fire Organizing Committee/John Brown Book Club Prairie Fire Organizing Committee Publications Date Range Organizational Body Subjects Formats General Description of Publication 1976-1995 Prairie Fire Organizing Prison, Political Prisoners, Human Rights, Black liberation, Periodicals, Publications by John Brown Book Club include Breakthrough, Committee/John Brown Book Chicano, Education, Gay/Lesbian, Immigration, Indigenous pamphlets political journal of Prairie Fire Organizing Committee (PFOC), Club struggle, Middle East, Militarism, National Liberation, Native published from 1977 to 1995; other documents published by American, Police, Political Prisoners, Prison, Women, AIDS, PFOC Anti-imperialism, Anti-racism, Anti-war, Apartheid, Aztlan, Black August, Clandestinity, COINTELPRO, Colonialism, Gender, High School, Kurds, Egypt, El Salvador, Eritrea, Feminism, Gentrification, Haiti, Israel, Nicaragua, Palestine, Puerto Rico, Racism, Resistance, Soviet Union/Russia, Zimbabwe, Philippines, Male Supremacy, Weather Underground Organization, Namibia, East Timor, Environmental Justice, Bosnia, Genetic Engineering, White Supremacy, Poetry, Gender, Environment, Health Care, Eritrea, Cuba, Burma, Hawai'i, Mexico, Religion, Africa, Chile, For other information about Prairie Fire Organizing Committee see the website pfoc.org [doesn't exist yet]. Freedom Archives [email protected] DOC 501 Prairie Fire Organizing Committee/John Brown Book Club Prairie Fire Organizing Committee Publications Keywords Azania, Torture, El Salvador, -

For Better Or for Worse: Coming out in the Funny Pages Bonnie Brennen Marquette University, [email protected]

Marquette University e-Publications@Marquette College of Communication Faculty Research and Communication, College of Publications 10-1-1995 For Better or For Worse: Coming Out in the Funny Pages Bonnie Brennen Marquette University, [email protected] Sue A. Latky University of Iowa Published version. Studies in Popular Culture, Vol. 18, No. 1 (October 1995): 23-47. Publisher Link. © 1995 Popular Culture Association in the South. Used with permission. Bonnie Brennen was affiliated with SUNY at the time of publication. Sue A. La(ky and Bonnie Brennen For Better or For Worse: Coming Out in the Funny Pages Among the most significant occasions in the lives of gay men and lesbians is the one in which they realize that their sexual orientation situates them as "other." One aspect of this process, known as coming out, is the self-acknowledgement ofbeing gay or lesbian, while another aspect consists of revealing this identity to family members and friends. During her 1980s fieldwork with lesbians and gay men in San Francisco, anthropologist Kath Weston observed that "no other topic generated an emotional response comparable to coming out to blood (or adoptive) relatives" (1991, 43). She wrote: When discussion turned to the subject of straight family, it was not unusual for interviews to be interrupted by tears, rage, or a lengthy silence. "Are you out to your parents?" and "Are you out to your family?" were questions that almost inevitably arose in the process of getting to know another lesbian or gay person. ( 43) In Spring of 1993, such a "coming out" process was played out in North American newspapers through Canadian artist Lynn Johnston's syndicated comic strip, For Better or For Worse. -

Police Charge Student in Ashby Room Wrecking

w e cBt&eze Jamca Madison University Monday, December e, 19S2 Vol.00 No.25 SGA committee Police charge student wants half kegs in Ashby room wrecking Student Government Association By GREG HENDERSON of why Duda and Smith's room was damaged. "I members are pushing to legalize the use of A JMU student has been arrested in connection don't even know them." one-half kegs for dorm parties. with the wrecking of a room in Ashby Hall Friday Balenger does not live in Ashby. He lives in the Currently, university policy allows dnly night. Sigma Phi Epsilon fraternity house, but said the quarter-kegs at dorm parties. Steven W. Balenger, 20, a junior from Leesburg, fraternity had nothing to do with Friday night's in- The Student Services Committee of the Va., was charged with assault and battery of a cident. SGA recently sent a letter to housing police officer, destruction of public property, and Duda said Balenger had told him Saturday that director James Krivoski. The main thrust public drunkenness, according to Rockingham he had had a disagreement with a resident of of the letter was that one one-half keg County jail records. Spotswood Hall, and he thought he was in that costs less than two one-quarter kegs. Witnesses said a man broke into Ashby room 19 person's room. Dave Harvey, the committee's chair- about 9:15 p.m. Friday and began destroying Balenger refused to comment on this. man, said, "To us, it's just a question of things. No one was in the room when the man first Balenger also would not comment on whether he practicality." broke in.