Sharp,Marsha2015-06-01Transcript.Pdf (883.8Kb)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

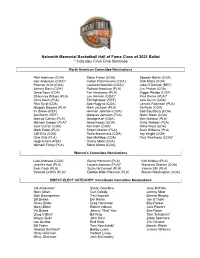

Naismith Memorial Basketball Hall of Fame Class of 2021 Ballot * Indicates First-Time Nominee

Naismith Memorial Basketball Hall of Fame Class of 2021 Ballot * Indicates First-Time Nominee North American Committee Nominations Rick Adelman (COA) Steve Fisher (COA) Speedy Morris (COA) Ken Anderson (COA)* Cotton Fitzsimmons (COA) Dick Motta (COA) Fletcher Arritt (COA) Leonard Hamilton (COA)* Jake O’Donnell (REF) Johnny Bach (COA) Richard Hamilton (PLA) Jim Phelan (COA) Gene Bess (COA) Tim Hardaway (PLA) Digger Phelps (COA) Chauncey Billups (PLA) Lou Henson (COA)* Paul Pierce (PLA)* Chris Bosh (PLA) Ed Hightower (REF) Jere Quinn (COA) Rick Byrd (COA) Bob Huggins (COA) Lamont Robinson (PLA) Muggsy Bogues (PLA) Mark Jackson (PLA) Bo Ryan (COA) Irv Brown (REF) Herman Johnson (COA) Bob Saulsbury (COA) Jim Burch (REF) Marques Johnson (PLA) Norm Sloan (COA) Marcus Camby (PLA) George Karl (COA) Ben Wallace (PLA) Michael Cooper (PLA)* Gene Keady (COA) Chris Webber (PLA) Jack Curran (COA) Ken Kern (COA) Willie West (COA) Mark Eaton (PLA) Shawn Marion (PLA) Buck Williams (PLA) Cliff Ellis (COA) Rollie Massimino (COA) Jay Wright (COA) Dale Ellis (PLA) Bob McKillop (COA) Paul Westhead (COA)* Hugh Evans (REF) Danny Miles (COA) Michael Finley (PLA) Steve Moore (COA) Women’s Committee Nominations Leta Andrews (COA) Becky Hammon (PLA) Kim Mulkey (PLA) Jennifer Azzi (PLA) Lauren Jackson (PLA)* Marianne Stanley (COA) Swin Cash (PLA) Suzie McConnell (PLA) Valerie Still (PLA) Yolanda Griffith (PLA)* Debbie Miller-Palmore (PLA) Marian Washington (COA) DIRECT-ELECT CATEGORY: Contributor Committee Nominations Val Ackerman* Simon Gourdine Jerry McHale Marv -

2020-21 Middle Tennessee Women's Basketball

2020-21 MIDDLE TENNESSEE WOMEN’S BASKETBALL Tony Stinnett • Associate Athletic Communciations Director • 1500 Greenland Drive, Murfreesboro, TN 37132 • O: (615) 898-5270 • C: (615) 631-9521 • [email protected] 2020-21 SCHEDULE/RESULTS GAME 22: MIDDLE TENNESSEE VS. LA TECH/MARSHALL Thursday, March 11 , 2021 // 2:00 PM // Frisco, Texas OVERALL: 14-7 C-USA: 12-4 GAME INFORMATION THE TREND HOME: 8-5 AWAY: 6-2 NEUTRAL: 0-0 Venue: Ford Center at The Star (12,000) Location: Frisco, Texas NOVEMBER Tip-Off Time: 2:00 PM 25 No. 5 Louisville Cancelled Radio: WGNS 100.5 FM, 101.9 FM; 1450-AM Talent: Dick Palmer (pxp) 29 Vanderbilt Cancelled Television: Stadium Talent: Chris Vosters (pxp) DECEMBER John Giannini (analyst) 6 Belmont L, 64-70 Live Stats: GoBlueRaiders.com ANASTASIA HAYES is the Conference USA Player of the 9 Tulane L, 78-81 Twitter Updates: @MT_WBB Year. 13 at TCU L, 77-83 THE BREAKDOWN 17 Troy W, 92-76 20 Lipscomb W, 84-64 JANUARY 1 Florida Atlantic* W, 84-64 2 Florida Atlantic* W, 66-64 8 at FIU* W, 69-65 9 at FIU* W, 99-89 LADY RAIDERS (14-7) C-USA CHAMPIONSHIP 15 Southern Miss* W, 78-58 Location: Murfreesboro, Tenn. Location: Frisco, Texas 16 Southern Miss* L, 61-69 Enrollment: 21,720 Venue: Ford Center at The Star 22 at WKU* (ESPN+) W, 75-65 President: Dr. Sidney A. McPhee C-USA Championship Record: 10-4 Director of Athletics: Chris Massaro All-Time Conf. Tourn. Record: 61-23 23 at WKU* (ESPN+) W, 77-60 SWA: Diane Turnham Tourn. -

2016-17 WOMEN's BASKETBALL ETBALL Baylor Lady Bears

2016-17 WOMEN’S BASKETBALL 2016-17 WOMEN’S BASKETBALL Baylor Lady Bears ROSTER TEAM INFORMATION No. Name Pos. Ht. Cl/Exp Hometown/HS/College Letterwinners Returning/Lost: 10/4 21 Kalani Brown C 6-7 So/1L Slidell, La./Salmen Starters Returning/Lost: 4/1 55 Khadijiah Cave C 6-3 Sr/3L Augusta, Ga./Lucy Laney 24 Natalie Chou G 6-1 Fr/HS Plano, Texas/Plano West Starters Returning: 4 1 Dekeiya Cohen F 6-2 Jr/2L Charleston, S.C./West Ashley Nina Davis, F, 5-11, Sr, 16.3 ppg, 6.1 rpg 15 Lauren Cox F 6-4 Fr/HS Flower Mound, Texas/Flower Mound Alexis Jones, G, 5-9, Sr, 15.0 ppg, 4.2 rpg 13 Nina Davis F 5-11 Sr/3L Memphis, Tenn./Memphis Central Beatrice Mompremier, C, 6-4, So, 7.2 ppg, 6.1 rpg 25 Alyssa Dry G 5-7 So/1L Fort Worth, Texas/IMG Academy (Fla.) Kristy Wallace, G, 5-11, Jr, 8.1 ppg, 3.3 rpg 10 Alexandria Gulley G 5-7 Fr/RS Dallas, Texas/Skyline 30 Alexis Jones G 5-9 Sr/1L Irving, Texas/MacArthur/Duke Starters Lost: 1 20 Calveion Landrum G 5-9 Fr/HS Waco, Texas/La Vega Niya Johnson, G, 5-8, 6.9 ppg, 5.2 rpg 32 Beatrice Mompremier C 6-4 So/1L Miami, Fla./Miami 12 Alexis Prince G 6-2 Sr/3L Orlando, Fla./Edgewater Other Returners: 6 4 Kristy Wallace G 5-11 Jr/2L Loganholme, Queensland, Australia/ Kalani Brown, C, 6-7, So, 9.3 ppg, 4.3 rpg John Paul College Khadijiah Cave, C, 6-3, Sr, 6.3 ppg, 4.9 rpg Dekeiya Cohen, F, 6-2, Jr, 2.5 ppg, 2.0 rpg Alyssa Dry, G, 5-7, So, 0.0 ppg, 0.5 rpg Alexis Prince, G, 6-2, Sr, 6.0 ppg, 3.8 rpg Alexandria Gulley, G, 5-7, Fr/RS SCHEDULE Others Lost: 3 Chardonae Fuqua’, F, 6-0, 0.4 ppg, 0.5 rpg NOVEMBER Kristina Higgins, C, 6-5, Sr, 3.2 ppg, 3.8 rpg 1 Emporia State [Exhibition] Waco 7:00 p.m. -

Women's Basketball Award Winners

WOMEN’S BASKETBALL AWARD WINNERS All-America Teams 2 National Award Winners 15 Coaching Awards 20 Other Honors 22 First Team All-Americans By School 25 First Team Academic All-Americans By School 34 NCAA Postgraduate Scholarship Winners By School 39 ALL-AMERICA TEAMS 1980 Denise Curry, UCLA; Tina Division II Carla Eades, Central Mo.; Gunn, BYU; Pam Kelly, Francine Perry, Quinnipiac; WBCA COACHES’ Louisiana Tech; Nancy Stacey Cunningham, First selected in 1975. Voted on by the Wom en’s Lieberman, Old Dominion; Shippensburg; Claudia Basket ball Coaches Association. Was sponsored Inge Nissen, Old Dominion; Schleyer, Abilene Christian; by Kodak through 2006-07 season and State Jill Rankin, Tennessee; Lorena Legarde, Portland; Farm through 2010-11. Susan Taylor, Valdosta St.; Janice Washington, Valdosta Rosie Walker, SFA; Holly St.; Donna Burks, Dayton; 1975 Carolyn Bush, Wayland Warlick, Tennessee; Lynette Beth Couture, Erskine; Baptist; Marianne Crawford, Woodard, Kansas. Candy Crosby, Northern Ill.; Immaculata; Nancy Dunkle, 1981 Denise Curry, UCLA; Anne Kelli Litsch, Southwestern Cal St. Fullerton; Lusia Donovan, Old Dominion; Okla. Harris, Delta St.; Jan Pam Kelly, Louisiana Tech; Division III Evelyn Oquendo, Salem St.; Irby, William Penn; Ann Kris Kirchner, Rutgers; Kaye Cross, Colby; Sallie Meyers, UCLA; Brenda Carol Menken, Oregon St.; Maxwell, Kean; Page Lutz, Moeller, Wayland Baptist; Cindy Noble, Tennessee; Elizabethtown; Deanna Debbie Oing, Indiana; Sue LaTaunya Pollard, Long Kyle, Wilkes; Laurie Sankey, Rojcewicz, Southern Conn. Beach St.; Bev Smith, Simpson; Eva Marie St.; Susan Yow, Elon. Oregon; Valerie Walker, Pittman, St. Andrews; Lois 1976 Carol Blazejowski, Montclair Cheyney; Lynette Woodard, Salto, New Rochelle; Sally St.; Cindy Brogdon, Mercer; Kansas. -

Cal's Joanne Boyle Honored with 2011 Carol Eckman Award 2010

Cal's Joanne Boyle Honored with 2011 Carol Eckman Award ATLANTA - Joanne Boyle, head coach of the University of California Golden Bears, is the winner of the 2011 Carol Eckman Award, the Women's Basketball Coaches Association (WBCA) announced today. The Carol Eckman Award is presented annually to an active WBCA coach who exemplifies Eckman's spirit, integrity and character through sportsmanship, commitment to the student-athlete, honesty, ethical behavior, courage and dedication to purpose. The award is named in honor of the late Carol Eckman, the former West Chester State College coach who is considered the "Mother of the Women's Collegiate Basketball Championship." Eckman organized the first women's basketball championship at West Chester in 1969 and continued to garner recognition and support for the women's game until her death from cancer in 1985. "We are pleased to present Joanne Boyle with the 2011 Carol Eckman Award," said WBCA CEO Beth Bass. "This award recognizes all the wonderful qualities and core values - sportsmanship, honesty and ethical behavior - inherent in educational athletics. Carol Eckman instilled in her players exactly those qualities that we aspire to foster through our Center for Coaching Excellence, which is housed at Columbia University." Boyle is in her sixth season as head coach of the Golden Bears, where she has amassed a 134-62 record. Under Boyle's direction, Cal registered four consecutive NCAA Tournament berths from 2006 through 2009, when it made its first-ever Sweet 16 appearance, and was the 2010 WNIT champion. This year's team is 15-14 heading into the Pac-10 Conference Tournament. -

Naismith Memorial Basketball Hall of Fame Announces Thirteen Finalists for Class of 2018 Election - Saturday, February 17, 2018

Naismith Memorial Basketball Hall of Fame Announces Thirteen Finalists for Class of 2018 Election - Saturday, February 17, 2018 - LOS ANGELES, CA – The Naismith Memorial Basketball Hall of Fame announced today, at NBA All-Star Weekend, eight phenomenal players, three standout coaches, one exceptional referee, and one record-setting team as finalists from the North American and Women’s committees to be considered for election in 2018. This year’s list includes six first-time finalists: two-time NBA Champion Ray Allen , two-time NCAA Champion Grant Hill , 10-time NBA All-Star Jason Kidd , two-time NBA MVP Steve Nash , three- time Olympic gold medalist Katie Smith and four-time WNBA Champion Tina Thompson . Previous finalists included again this year for consideration are four-time NBA All-Star Maurice Cheeks , the only coach in NCAA history to be named Conference Coach of the Year in four different conferences Charles “Lefty” Driesell , 28-year NBA referee Hugh Evans , two-time NCAA National Championship Coach of Baylor Kim Mulkey , two-time NBA Champion coach Rudy Tomjanovich , five-time NBA All-Star Chris Webber and 10-time AAU National Champions Wayland Baptist University. “To be named a Finalist for the Basketball Hall of Fame is an incredible distinction and we are proud to honor those who have made a tremendous impact on the game over the years,” said Jerry Colangelo, Chairman of the Naismith Memorial Basketball Hall of Fame. “The Honors Committee now has the challenging task of selecting this year’s Enshrinees, which we look forward to announcing at the NCAA Final Four in San Antonio.” Announced in December, two distinct modifications have been made to the election process. -

West Chester's Deirdre Kane to Receive WBCA's Carol Eckman Award

West Chester's Deirdre Kane to Receive WBCA's Carol Eckman Award ATLANTA, Ga. (March 10, 2004) -- The Women's Basketball Coaches Association (WBCA) has announced Deirdre Kane as the winner of its Carol Eckman Award. The Carol Eckman Award is presented annually to an active WBCA coach who exemplifies Eckman's spirit, integrity and character through sportsmanship, commitment to the student-athlete, honesty, ethical behavior, courage and dedication to purpose. The award is named in honor of the late Carol Eckman, the former West Chester State College coach who is considered the "Mother of the Women's Collegiate Basketball Championship." Eckman organized the first women's basketball championship at West Chester in 1969 and continued to garner recognition and support for the women's game until her death from cancer in 1985. "It's quite amazing to see the legacy of Coach Eckman's spirit live on through one of her successors," said WBCA CEO, Beth Bass. "Deirdre has done an outstanding job maintaining the integrity of the West Chester women's basketball program." Kane is the head women's basketball coach at West Chester University. She has won over 200 games, more than any women's basketball coach in the school's history. Last season, she led the team to the program's first PSAC Championship game and their first NCAA Division II Tournament win. Kane's past honors include WBCA District II Coach of the Year and PSAC Eastern Division Coach of the Year, an honor she received for two consecutive seasons. Kane will receive her award at the State Farm Wade Trophy and State Farm/WBCA Player of the Year Luncheon, presented by Jostens. -

Lubbock, Texas FY 2006-07 to FY 2011-12 Adopted Capital Improvement Program

Fiscal Year 2006-07 to 2011-2012 Adopted Capital Improvement Program Partnering to build the model community. City of Lubbock, Texas FY 2006-07 to FY 2011-12 Adopted Capital Improvement Program City Council David A. Miller Mayor Jim Gilbreath Mayor Pro Tem - District 6 Linda DeLeon Council Member - District 1 Floyd Price Council Member - District 2 Gary O. Boren Council Member - District 3 Phyllis S. Jones Council Member - District 4 John W. Leonard, III Council Member - District 5 Senior Management Lee Ann Dumbauld City Manager Anita Burgess City Attorney Becky Garza City Secretary Thomas Adams Deputy City Manager Jeffrey A. Yates Chief Financial Officer Finance Staff Andy Burcham Director of Strategic Planning & Fiscal Policy Melissa Trevino Fiscal Policy Manager Justin Nairn Capital Projects Manager Brandon Inman Senior Financial Analyst Oxana Moreno Financial Analyst GFOA Distinguished Budget Presentation Award City of Lubbock, TX The Government Finance Officers Association of the United States and Canada (GFOA) presented a Distinguished Budget Presentation Award to the City for its annual budget for the fiscal year beginning October 1, 2005. In order to receive this award, a governmental unit must publish a budget document that meets program criteria as a policy document, as an operations guide, as a financial plan, and as a communications device. This award is valid for a period of one year only. We believe our current budget continues to conform to program requirements, and we are submitting it to GFOA to determine its eligibility -

De Paul Basketball

DE PAUL BASKETBALL 2007-08 SEASON-IN-REVIEW Nation’s ONLY PROGRAM IN NCAA CHAMPIONSHIP & WBCA ACADEMIC TOP 25 IN EACH OF LAST TWO SEASONS 16 20-WIN SEASONS H 13 NCAA CHAMPIONSHIP APPEARANCES H .845 WINNING PERCENTAGE AT McGRATH ARENA 2007-08 QUICK FACTS SCHEDULE/RESULTS DE PAUL UNIVERSITY November Location ............................................................................................................. Chicago, Ill. 10 at Southern Illinois ........................ W, 78-63 Founded .......................................................................................................................1898 DePaul Invitational (Chicago, Ill.) Denomination ............................................................................................. Roman Catholic 15 Florida International ..................... W, 89-77 Conference .......................................................................................................... BIG EAST 16 #18/19 Florida State ..................... W, 79-68 25 at Illinois State .............................. W, 80-75 Enrollment ................................................................................. 24,148 (14,740 undergrad) 29 Illinois-Chicago ............................. W, 74-35 Nickname........................................................................................................ Blue Demons Colors .............................................................................................. Royal Blue and Scarlet December Home Arena (Capacity) .................................................................. -

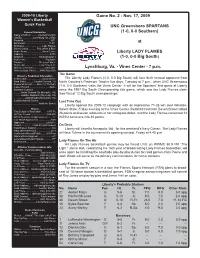

09-10 Game 2 UNCG.Indd

22009-10009-10 LibertyLiberty Game No. 2 - Nov. 17, 2009 WWomen’somen’s BBasketballasketball QQuickuick FFactsacts UNC Greensboro SPARTANS GGeneraleneral IInformationnformation (1-0, 0-0 Southern) NNameame ooff SSchoolchool ...................... LLibertyiberty UUniversityniversity CCity/Zipity/Zip .................................. LLynchburg,ynchburg, VVa.a. 2450224502 FFoundedounded ....................................................................................11971971 EEnrollmentnrollment ........................................................................ 111,3111,311 at NNicknameickname........................................................ LLadyady FFlameslames SSchoolchool ColorsColors ........................ RRed,ed, WWhitehite & BBluelue HHomeome AArenarena................................................ VVinesines CCenterenter Liberty LADY FLAMES CCapacityapacity....................................................................................88,085,085 AAfffi lliationiation ................................................ NNCAACAA DDivisionivision I (1-0, 0-0 Big South) CConferenceonference ............................................................ BBigig SSouthouth FFounderounder .................................................. DDr.r. JJerryerry FFalwellalwell CChancellorhancellor ..........................................JJerryerry FFalwell,alwell, JJr.r. DDirectorirector ooff AAthleticsthletics................................ JJeffeff BBarberarber Lynchburg, Va. - Vines Center - 7 p.m. AAthleticsthletics -

Frese's Coaching Record Against All Opponents

2008-09 Outlook Coaching Staff BRENDA Terrapin Profiles Terrapin The ACC The FRHead CoaCH • aESErizona ‘93 SEVENTH YEAR AT MARYLAND (145-55, .725) 10TH YEAR AS A HEAD COACH (202-85, .704) Opponents 2002 AP COACH OF THE YEAR There was no better fit for the University of Maryland women’s basketball program than head coach Brenda Frese. The 2002 Associated Press National Coach of the Year arrived in College Park with great expectations and has not disappointed. Re- 2007-08 Review viving a once-prominent women’s basketball program back to the national stage, her high work rate and positive attitude has resulted in six-straight top-10 recruit- ing classes and a National Championship in 2006. Frese has balanced that strong work ethic with a fun and family-friendly environment, also becom- Record Book ing a wife and a mother of twin boys, giving birth to them in the midst of one of the most successful seasons in the progam’s history. With the birth of her twins in February, she becomes one of only six coaches to win a national championship and All-Time Honors All-Time be a parent. The University 42 six-straigHt top 10 reCruiting Classes 2008-09 Outlook 2002-03 2003-04 2004-05 2005-06 2006-07 2007-08 NO. 10 NO. 2 NO. 4 NO. 7 NO. 2 NO. 10 Since her first season at the helm when the team won Frese has built the team’s success around recruiting, just 10 games, Frese has guided Maryland to a National hard work and a positive atmosphere. -

Campbellsville University's Donna Wise Receives WBCA's Jostens-Berenson Lifetime Achievement Award

Campbellsville University's Donna Wise Receives WBCA's Jostens-Berenson Lifetime Achievement Award ATLANTA - Donna Wise, the all-time winningest coach at Campbellsville (Ky.) University, will receive the 2011 Jostens-Berenson Lifetime Achievement Award in recognition of her lifelong commitment of service to women's basketball, the Women's Basketball Coaches Association (WBCA) announced today. "It gives me great pleasure to announce Donna Wise as the winner of the Jostens- Berenson Lifetime Achievement Award," said WBCA CEO Beth Bass. "This award, which is named for the mother of the women's game, is the highest honor the WBCA can bestow on an individual." Wise compiled a 661-283 record in her 32-year career at Campbellsville. Her teams made 16 NAIA National Tournament appearances, reaching the Elite Eight five times. Under her direction, the Lady Tigers won 20 Mid-South and KIAC Conference regular season championships and 15 NAIA conference championships. Wise's program produced 23 All-Americans. She was named NAIA Coach of the Year three times and received conference coach of the year honors seven times. Wise previously has been recognized for her lifetime achievement with induction into the NAIA Basketball Hall of Fame in 2000 and the Kentucky Athletic Hall of Fame in 2010. Wise retired as women's basketball coach in 2007. She remains at Campbellsville as head of the university's Department of Human Performance. "We are thrilled to recognize Donna Wise with the Jostens-Berenson Lifetime Achievement Award," said Nicole Ellos, Manager Jostens Championship Sports Marketing "It is an honor to help recognize such an amazing career filled with accomplishments and to celebrate Coach Wise's commitment to her players, her university and to women's basketball." Wise will be formally recognized during the WBCA Awards Show, which will be held at 6 pm EDT Monday, April 4, in the Indianapolis Convention Center's Sagamore Ballroom.