The Archaeologists Sheila Sleath and Robert Ovens

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Empingham Village Walk 23 September 2006 (Updated 2020)

Thomas Blore in The History and Antiquities of the Rutland Local History & County of Rutland (Vol. 1, Pt. 2, 1811) notes that there was a chapel of St. Botolph in what is now Chapel Spinney on Record Society Chapel Hill to the east of the village. The location is Registered Charity No. 700273 marked on some old maps. Empingham Village Walk 23 September 2006 (updated 2020) Copyright © Rutland Local History and Record Society All rights reserved INTRODUCTION Chapel of St Botolph on John Speed's map of c1610 Empingham lies in the Gwash Valley, near the eastern end of Rutland Water. When the reservoir was under Earthworks in Hall Close, to the south-west of the construction in the early 1970s archaeological excavations village, ([20] on the walk map, but not part of this walk) confirmed that this area had been occupied for many mark the moated site of a manor house, probably the hall centuries. Discoveries included: which Ralph de Normanville was building in 1221. It is • Traces of an Iron Age settlement recorded that the king, Henry III, gave instructions for • Two Romano-British farming settlements Ralph to take six oak trees from the forest to make crucks • Pagan and Christian Anglo-Saxon cemeteries for this project (Victoria County History, A History of the The most enduring legacy the Saxons left to County of Rutland, Volume 2, 1935) Empingham was its name. The ending ‘ingham’ denotes one of the earlier settlements, older than those with ‘ham’ and ‘ton’ endings. So Empingham was the home of the ‘ing’ or clan of Empa. -

Sd12b Baseline Scoping Report 2016–2036

Langham Neighbourhood Plan Support Document SD12b Baseline Scoping Report 2016–2036 Final Document January 2017 Final - January 2017 Contents Contents 1 Associated Documents and Appendices 2 Maps showing potential development sites outside Planned Limits of Development 3 1. Foreword 4 2. Introduction 4 The Scoping report 5 Langham Neighbourhood Plan 7 3. Relevant Plans, Programmes & Sustainability Objectives (Stage 1) 9 Policy Context 9 International Context 9 National Context 10 Local Context 10 4. Baseline Data & Key Sustainability Issues (Stages 2 & 3) 11 Langham Parish Appraisal (RCC) 11 SEA Topics 12 Relevance to Langham Neighbourhood Plan (LNP) 13 SEA Analysis by Topic 15 a) Nature Conservation 15 b) Landscape 20 c) Water 23 d) Soils and Agricultural Land 26 e) Cultural Heritage 29 f) Air Quality and Climate 31 g) Human Characteristics 32 h) Roads and Transport 35 i) Infrastructure 38 j) Economic Characteristics 39 5. Key Sustainability Issues 40 Community Views 40 SWOT Analysis 41 6. Identifying Sustainability Issues & Problems Facing Langham 42 7. Strategic Environmental Assessment Appraisal Framework (Stage 4) 45 8. Conclusions and Next Steps 48 NB This Report must be read in association with the listed Support Documents Associated Documents 1 Final - January 2017 SEA Baseline & Scoping Report LNP Associated Document 1: Langham Neighbourhood Plan 2016 – Main Plan Associated Documents 2: SD2, 2a, 2b and 2c – Consultation & Response Associated Document 3: SD4 Housing & Renewal, SD4a Site Allocation Associated Document 4: SD5 Public -

9 Bus Time Schedule & Line Route

9 bus time schedule & line map 9 Oakham - Stamford View In Website Mode The 9 bus line (Oakham - Stamford) has 2 routes. For regular weekdays, their operation hours are: (1) Oakham: 8:23 AM - 4:45 PM (2) Stamford: 7:53 AM - 3:55 PM Use the Moovit App to ƒnd the closest 9 bus station near you and ƒnd out when is the next 9 bus arriving. Direction: Oakham 9 bus Time Schedule 22 stops Oakham Route Timetable: VIEW LINE SCHEDULE Sunday Not Operational Monday 8:23 AM - 4:45 PM Bus Station, Stamford 12 All Saints Street, Stamford Tuesday 8:23 AM - 4:45 PM All Saints' Church, Stamford Wednesday 8:23 AM - 4:45 PM 12 All Saints Place, Stamford Thursday 8:23 AM - 4:45 PM Beverley Gardens, Stamford Friday 8:23 AM - 4:45 PM Casterton Road, Stamford Saturday Not Operational Waverley Gardens, Stamford Caledonian Road, Stamford Ayr Close, Stamford 9 bus Info Casterton Road, Stamford Civil Parish Direction: Oakham Stops: 22 Belvoir Close, Stamford Trip Duration: 27 min Line Summary: Bus Station, Stamford, All Saints' Arran Road (North End), Stamford Church, Stamford, Beverley Gardens, Stamford, Waverley Gardens, Stamford, Caledonian Road, Sidney Farm Lane, Stamford Stamford, Ayr Close, Stamford, Belvoir Close, Stamford, Arran Road (North End), Stamford, Sidney Tolethorpe, Great Casterton Farm Lane, Stamford, Tolethorpe, Great Casterton, Church, Great Casterton, The Plough, Great Church, Great Casterton Casterton, Bus Shelter, Tickencote, School Lane, Empingham, Wiloughby Drive, Empingham, Exton The Plough, Great Casterton Road, Empingham, Rutland Water -

The Heritage of Rutland Water

Extra.Extra pages 7/10/07 15:28 Page 1 Chapter 30 Extra, Extra, Read all about it! Sheila Sleath and Robert Ovens The area in and around the Gwash Valley is not short of stories and curiosities which make interesting reading. This chapter brings together a representative sample of notable personalities, place names, extraordinary events, both natural and supernatural, and tragedies including murder most foul! The selected items cover a period of eight hundred years and are supported by extracts and images from antiquarian sources, documentary records, contemporary reports and memorials. A Meeting Place for Witches? The name Witchley originates from the East and West Witchley Hundreds which, in 1086, were part of north Northamptonshire. However, following a boundary change a few years later, they became East Hundred and Wrangdike Hundred in the south-east part of Rutland. Witchley Heath, land lying within an area approximately bounded by Normanton, Empingham and Ketton, was named as a result of this historical association. It is shown on Morden’s 1684 map and other seventeenth and eighteenth century maps of Rutland. Witches Heath, a cor- ruption of Witchley Heath, is shown on Kitchin and Jeffery’s map of 1751. The area of heathland adjacent to the villages of Normanton, Ketton and Empingham became known locally as Normanton Heath, Ketton Heath and Empingham Heath. By the nine- teenth century the whole area was Kitchin and better known as Empingham Heath. The name Witchley was, however, Jeffery’s map of retained in Witchley Warren, a small area to the south-east of Normanton 1751 showing Park, and shown on Smith’s map of 1801. -

Landscape Character Assessment of Rutland (2003)

RUTLAND LANDSCAPE CHARACTER ASSESSMENT BY DAVID TYLDESLEY AND ASSOCIATES Sherwood House 144 Annesley Road Hucknall Nottingham NG15 7DD Tel 0115 968 0092 Fax 0115 968 0344 Doc. Ref. 1452rpt Issue: 02 Date: 31st May 2003 Contents 1. Purpose of this Report 1 2. Introduction to Landscape Character Assessment 2 3. Landscape Character Types in Rutland 5 4. The Landscape of High Rutland 7 Leighfield Forest 8 Ridges and Valleys 9 Eyebrook Valley 10 Chater Valley 11 5. The Landscape of the Vale of Catmose 15 6. The Landscape of the Rutland Water Basin 18 7. The Landscape of the Rutland Plateau 20 Cottesmore Plateau 21 Clay Woodlands 23 Gwash Valley 24 Ketton Plateau 25 8. The Landscape of the Welland Valley 28 Middle Valley West 28 Middle Valley East 29 Figures and Maps Figure 1 Landscape Character Types and Sub-Areas Figure 2 Key to 1/25,000 Maps Maps 1 - 10 Detailed 1/25,000 maps showing boundaries of Landscape Character Types and Sub-Areas Photographs Sheet 1 High Rutland and Welland Valley Sheet 2 Vale of Catmose and Rutland Water Basin Sheet 3 Rutland Plateau References 1 Leicestershire County Council, 1976, County Landscape Appraisal 2 Leicestershire County Council, 1995 published 2001, Leicester, Leicestershire and Rutland Landscape and Woodland Strategy 3 Countryside Agency and Scottish Natural Heritage, 2002, Landscape Character Assessment Guidance for England and Scotland 4 Institute of Environmental Management and Assessment and the Landscape Institute, 2002, Guidelines for Landscape and Visual Impact Assessment, Spons 5 Countryside Agency and English Nature, 1997, The Character of England: Landscape Wildlife and Natural Features and Countryside Agency, 1999, Countryside Character Volume 4: East Midlands 6 Department of Environment, 1997 Planning Policy Guidance 7 The Countryside - Environmental Quality and Economic and Social Development RUTLAND LANDSCAPE CHARACTER ASSESSMENT DTA 2003 1. -

Ash House Empingham 2 3

ASH HOUSE EMPINGHAM 2 3 WELCOME TO ASH HOUSE Are you craving a bright and sociable detached family home that offers an idyllic village lifestyle yet is still close to fantastic amenities? Stone-built in 2013 and with seven years left on its new home builder’s guarantee, Ash House, Empingham, has five bedrooms with three en suites, four reception rooms and a gorgeous kitchen for entertaining. With the market towns of Stamford and Oakham nearby and Rutland Water on your doorstep, the location has something for everyone. EASY LIVING Ash House’s thoughtful layout grants a STEP INSIDE sense of grace alongside a natural flow. The neutral palette infuses the home with A few steps lead to the delightful stone If you turn right into the sitting room, you Returning through the hallway, peek in at hooks. A great place to concentrate while freshness and light, but it is also waiting for AN ATTRACTIVE APPROACH porch, which is handy for those rainy will find a spacious and bright area for the formal dining room. With excellent keeping an eye on the comings and goings you to stamp it with your style. days but doubles up as a beautiful feature the whole family to unwind come evening. proportions, bay windows and efficient of everyone else. As you arrive at the home, absorb the charm of the stone façade and those lovely bay in its own right. The fabulous entrance Open up the French doors to the rear lighting, you won’t need an excuse to host windows. With a large driveway and a brilliant double garage with an electric roller hall is warm and inviting thanks to pretty garden and let in the summer breeze, or a dinner party or invite your loved ones After returning from a ramble in the door – great for ease of access to swing your car in. -

Landscape Sensitivity & Capacity Study of Land North West of Oakham

LANDSCAPE SENSITIVITY AND CAPACITY STUDY OF LAND TO THE NORTH WEST OF OAKHAM, RUTLAND FINAL REPORT December 2018 by Report prepared by: Anthony Brown CMLI Chartered Landscape Architect Bayou Bluenvironment Limited Landscape Planning & Environmental Consultancy Cottage Lane Farm, Cottage Lane Collingham, Newark Nottinghamshire NG23 7LJ Tel. +44(0)1636 555006 Mobile: 07866 587108 [email protected] Document Ref: BBe2018/64: Final Report: 13 December 2018 Contents Page 1. Introduction and Executive Summary ........................................................................... 1 Background to and Outline of the Study .............................................................................. 1 Format of the Report ............................................................................................................ 3 Executive Summary ............................................................................................................... 4 2. Methodology ............................................................................................................... 5 3. Assessment & Analysis ........................................................................................... 15 Oakham Local Landscape Character Context ..................................................................... 15 Landscape Sensitivity and Capacity of Study Zones ........................................................... 22 Zone 1................................................................................................................................. -

Post Opening Project Evaluation A46 Newark to Widmerpool Improvement Scheme - Five Years After

Post Opening Project Evaluation A46 Newark to Widmerpool Improvement Scheme - Five Years After Post Opening Project Evaluation A46 Newark to Widmerpool Improvement Scheme - Five Years After Opening August 2017 1 Although this report was commissioned by Highways England, the findings and recommendations are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the views of the Highways England. While Highways England has made every effort to ensure the information in this document is accurate, Highways England does not guarantee the accuracy, completeness or usefulness of that information; and it cannot accept liability for any loss or damages of any kind resulting from reliance on the information or guidance this document contains. Post Opening Project Evaluation A46 Newark to Widmerpool Improvement Scheme - Five Years After Table of contents Chapter Pages Executive summary 4 Scheme Description 4 Scheme Objectives 4 Key Findings 4 Summary of Scheme Impacts 5 Summary of Scheme Economic Performance 6 1. Introduction 7 Background 7 Scheme Location 7 Problems Prior to the Scheme 8 Objectives 8 Scheme Description 8 Scheme History 10 Nearby Schemes 10 Overview of POPE 11 Contents of this Report 12 2. Traffic Analysis 13 Introduction 13 Data Sources 13 Background Changes in Traffic 17 Observed Traffic Flows 18 Forecast Traffic Flows 29 Journey Time Analysis 36 Journey Time Reliability 40 Key Points – Traffic 42 3. Safety Evaluation 43 Introduction 43 Data Sources 43 Collisions 44 Collision and Casualty Numbers 45 Forecast Collision Numbers and Rates 56 Security 59 Key Points – Safety 60 4. Economy 61 Introduction 61 Evaluation of Journey Time Benefits 62 Evaluation of Safety Benefits 64 Indirect Tax 66 Carbon Impact 67 Scheme Costs 67 Benefit Cost Ratio (BCR) 69 Wider Economic Impacts 69 Key Points – Economy 71 5. -

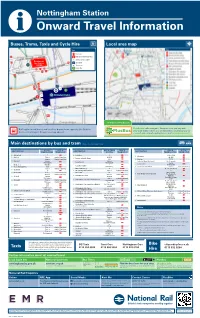

Destinations by Bus and Tram Buses, Trams, Taxis and Cycle Hire Local

Nottingham Station i Onward Travel Information Buses, Trams, Taxis and Cycle Hire Local area map Key C1 Bus Stop C1 Rail replacement Bus Stop Station Entrance/Exit Broadmarsh C9 Bus Station N6 Taxi Rank CLOSED Tram Stop C4 Cycle Hire C2 C3 C11 C12 C10 S1 S6 S2 S5 S3 S7 Nottingham Station S4 ME01 Nottingham is a PlusBus area Contains Ordnance Survey data © Crown copyright and database right 2020 & also map data © OpenStreetMap contributors, CC BY-SA Rail replacement buses and coaches depart from opposite the Station PlusBus is a discount price ‘bus pass’ that you buy with your train ticket. It gives you unlimited bus travel around your front, on Carrington Street (see map above). chosen town, on participating buses. Visit www.plusbus.info Main destinations by bus and tram (Data correct at August 2020) BUS & BUS & BUS & TRAM BUS & BUS & BUS & DESTINATION DESTINATION DESTINATION TRAM ROUTES TRAM STOP ROUTES TRAM STOP TRAM ROUTES TRAM STOP { Abbey Park 7 S7 { Lady Bay 11 S1 L1(Locallink) S3 { Silverdale { Basford Tram + Station Tram Stop 49, 49X S1 48, 48X S1 { Lenton Industrial Estate Tram ++ Station Tram Stop W1 S4 { Strelley 77, 78 C1 { Beeston ^ Skylink Skylink Tollerton (Main A606 road) The Keyworth S3 C10 Long Eaton ^ C10 Nottingham Nottingham Skylink Toton Corner C10 Bingham ^ Mainline S4 1 S2 Nottingham Loughborough ^ { Boots Headquarters 49X S1 9(Kinchbus) S3 { Toton Lane Park & Ride Tram ++ Station Tram Stop Tram + Station Tram Stop Melton Mowbray 19 ME01 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 9B, 10 S7 { Bulwell ^ 79 C1 { Moor Bridge (Bulwell Hall) Tram -

Welcome to Empingham Empingham Parish Council Chair: Vic Pheasant – 01780 460919

Useful contacts and numbers Welcome to Empingham Empingham Parish Council www.empinghamcouncil.org.uk Chair: Vic Pheasant – 01780 460919 Clerk: Mrs Rowan Scholtz – 01780 460557 Rutland County Council Catmose, Oakham LE15 6HP – 01572 722577—www.rutland.gov.uk Council tax, refuse and recycling, planning, social care, education, leisure and culture, electoral registration, etc. Empingham is part of Normanton Ward, which elects two councillors - currently Kenneth Bool (01572 813356) and Gale Waller (01780 722169) Recycling and waste Wheelie bin collection day for Empingham is Monday. Principal waste and recycling centres are: Cottesmore (Burley Road — LE15 7BZ) North Luffenham (Luffenham Road, Morcott— LE15 9DW) These are for use by local residents only. Register your car details with Rutland County Council before making your first visit. Village Website — http://www.empingham.life Operated by the Men’s Shed, this gives contact information for the activity groups in the village. It has a calendar of events and local weather is reported. Also a short history of the village and some photographs. Bus service The No. 9 bus service (Oakham—Stamford) travels through Empingham, with stops near the cemetery and along Main Street. See the bus stops for timetables, and for details of how to contact the operator. Anglian Water Services Water supply and sewage disposal. Something to add? Emergencies– 08457 145145 To update or correct anything in this Severn Trent Water Services leaflet, please contact: This leaflet, which is frequently updated, is designed in particular Water supply. [email protected] for newcomers to the village. We hope it will be useful and we look Emergencies – 0800 783 4444 forward to meeting you. -

Rushcliffe Air Quality Progress Report 2010/2011

Rushcliffe Borough Council May 2011 2011 Air Quality Progress Report for Rushcliffe Borough Council In fulfillment of Part IV of the Environment Act 1995 Local Air Quality Management Date May 2011 Progress Report i May 2011 Rushcliffe Borough Council Local Martin Hickey Authority Officer Department Environment & Waste Management Service Address Civic Centre, Pavilion Road West Bridgford Nottingham NG2 5FE Telephone 01159148486 e-mail [email protected] Report 2010/11 PR Reference number Date May 2011 ii Progress Report Rushcliffe Borough Council May 2011 Executive Summary This report provides an update with respect to air quality issues within the borough of Rushcliffe over the year 2010 and the progress of implementation of the measures outlined in the Air Quality Action Plan (AQAP), published initially in May 2007 (updated 2009) as required by the Environment Act 1995. Part IV of the Environment Act 1995 places a statutory duty on local authorities to review and assess the air quality within their area and take account of Government Guidance when undertaking such work. The AQAP contains a set of measures aimed at working toward ensuring the air quality in Rushcliffe meets the Air Quality Objectives set out in the National Air Quality Strategy due to excessive levels of Nitrogen Dioxide in air quality management areas (AQMA’s) within the Borough. Rushcliffe has two air quality management areas both of which have been declared due to traffic pollution and in particular due to excessive levels of the annual Nitrogen Dioxide above the air quality objective (AQO) level in certain areas. The areas covered by the AQMA’s are the Trent Bridge/Radcliffe Road/Wilford lane areas and part of the A52 ring road up to the Nottingham Knight traffic island. -

Local Flood Risk Management Strategy

LOCAL FLOOD RISK MANAGEMENT STRATEGY Version & Policy Number 1 Guardian Dave Brown, Director for Places (Environment, Planning & Transport) Date Produced 20 February 2018 Next Review Date 17 October 2022 Considered by Scrutiny 16 November 2017 Approved by Cabinet 17 April 2018 Appendix 1 - Rutland County Council - Local Flood Risk Management Strategy Summary of document This strategy will provide an overview for how the Council as the Lead Local Flood Authority (LLFA) will lead and co-ordinate local flood risk management in Rutland. It will act as the focal point for integrating all flood risk management functions in the County and has regard to the Environment Agency’s National Flood and Coastal Erosion Risk Management Strategy. The document provides a background to the need for such a strategy, detailing the local and national drivers whilst setting out where responsibility for different flood risks lay. The existing framework for managing and communicating flood risk is briefly described including how RCC are currently fulfilling their LLFA roles. The uplands of Rutland provide headwaters for three separate catchments, these relatively steep clay uplands appear conducive to flash flooding but historically the mapped risk and actual experience of flooding is somewhat limited, even during recent heavy rainfall events and as such the level of flood risk has been deemed to be relatively low in both local and national assessments. Two reservoirs dominate the landscape in the area and both are well managed and have a negligible flood risk being more significant for their wildlife designations and the amenity they provide to residents and visitors of the area.