Lessons from 3M Corporation: Managing Innovation Over Time and Overcoming the Innovator’S Dilemma

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

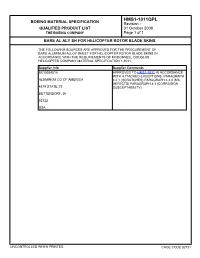

HMS1-1011QPL BOEING MATERIAL SPECIFICATION Revision - QUALIFIED PRODUCT LIST 31 October 2008 the BOEING COMPANY Page 1 of 1

HMS1-1011QPL BOEING MATERIAL SPECIFICATION Revision - QUALIFIED PRODUCT LIST 31 October 2008 THE BOEING COMPANY Page 1 of 1 BARE AL ALY SH FOR HELICOPTER ROTOR BLADE SKINS THE FOLLOWING SOURCES ARE APPROVED FOR THE PROCUREMENT OF BARE ALUMINUM ALLOY SHEET FOR HELICOPTER ROTOR BLADE SKINS IN ACCORDANCE WITH THE REQUIREMENTS OF MCDONNELL DOUGLAS HELICOPTER COMPANY MATERIAL SPECIFICATION 1-1011. Supplier Info Supplier Comments BE10034516 APPROVED TO HMS1-1011 IN ACCORDANCE WITH ATTACHED EXCEPTIONS. PARAGRAPH ALUMINUM CO OF AMERICA 4.2.1 (SCRATCHES) PARAGRAPH 4.2.2 (MIL DEFECTS) PARAGRAPH 4.3 (CORROSION 4879 STATE ST SUSCEPTABILITY) BETTENDORF, IA 52722 USA UNCONTROLLED WHEN PRINTED CAGE CODE 02731 HMS11-1109QPL BOEING MATERIAL SPECIFICATION Revision - QUALIFIED PRODUCT LIST 31 October 2008 THE BOEING COMPANY Page 1 of 2 TITANIUM FORGINGS BETA PROCESSED 6AL-4V THE FOLLOWING SOURCES ARE APPROVED FOR THE PROCUREMENT OF TITANIUM FORGINGS IN ACCORDANCE WITH THE REQUIREMENTS OF MCDONNELL DOUGLAS HELICOPTER COMPANY MATERIAL SPECIFICATION 11-1109. Supplier Info Supplier Comments BE10038732 PACIFIC FORGE INC 10641 ETIWANDA AVE FONTANA, CA 92337-6909 USA Supplier Info Supplier Comments BE10029768 RMI TITANIUM COMPANY 1000 WARREN AVE NILES, OH 44446-1168 USA Supplier Info Supplier Comments BE10037611 CONSOLIDATED INDUSTRIES, INC. 677 MIXVILLE RD CHESHIRE, CT 06410-3836 USA Supplier Info Supplier Comments BE10029096 MCWILLIAMS FORGE COMPANY INC 387 FRANKLIN AVE ROCKAWAY, NJ UNCONTROLLED WHEN PRINTED CAGE CODE 02731 Supplier Info Supplier Comments 07866-4000 USA HMS11-1109QPL Revision - Page 2 of 2 UNCONTROLLED WHEN PRINTED CAGE CODE 02731 HMS11-1110QPL BOEING MATERIAL SPECIFICATION Revision - QUALIFIED PRODUCT LIST 31 October 2008 THE BOEING COMPANY Page 1 of 1 TITANIUM ALLOY 6A1-4V PLATE; HIGH FRACTURE TOUGHNESS THE FOLLOWING SOURCES ARE APPROVED FOR THE PROCUREMENT OF TITANIUM ALLOY PLATE IN ACCORDANCE WITH THE REQUIREMENTS OF MDHC MATERIAL SPECIFICATION 11-1110. -

MINNESOTA MINING and MANUFACTURING (3M) MBA Tech

SVKM͛S NMIMS UNIVERSITY MUKESH PATEL SCHOOL OF TECHNOLOGY MANAGEMENT & ENGINEERING MANAGEMENT OF INNOVATION CASE STUDY MINNESOTA MINING AND MANUFACTURING (3M) MBA Tech. 4th Year (I.T), Shirpur By Rewat Singh Fageria Arpit Grover Uday Mittal Anubhav Saksena Sameer Tayal 1 | P a g e Table of Contents Serial No. Topic Page No. 1 The radical innovations 2 2 The incremental innovations 3 3 Was it a disruptive/radical innovation? 4 4 Dimensions of innovations 6 5 Categorization in the 4p¶s model 7 6 Process of innovation 8 7 Phase gate model 9 8 Drivers for the innovations 10 9 Discontinuity Triggers 10 Strategy Adopted 11 References 2 | P a g e What are radical innovations? Radical innovation is building a product or service that would have a revolutionary effect on the market and is often disruptive for the players in that market. A radically innovative product would have an entirely set on new features (e.g. Post-it) or major improvements on features of an existing product (e.g. Scotch Brite) or has a significant (30%) reduction in cost (e.g. Scotch Permanent Glue Stick, 3M Surgical masks). They may have competency destroying effects on an established organization. Minnesota Mining & Manufacturing or 3M, as they are known to the world, has been introducing radically innovative products for more than 100 years now. Their strategy to deal with radical innovation is based in following: y Setting stretch targets - such as µx% of sales from products introduced during the past y years¶ y Allocating resources as slack - space and time in which staff can explore and play with ideas, build on chance events or combinations, etc. -

COOL BOSS Case

Latest Court Decisions 2012: 〔July〕 ● COOL BOSS Case (Cancellation Suit of Trial Decision) IP High Court 2012.7.18 H23(Gyo-Ke)10436 An Invalidation Trial filed by Hugo Boss Trademark Management GmbH & KG against the registered trademark “COOL BOSS” in Katakana letters specifying “working wear with the ventilation function, non-Japanese style outer clothing, and coats” in Class 25 was dismissed by the JPO because the trademark “COOL BOSS” was not confusingly similar to the cited trademarks “BOSS/HUGO BOSS” and “BOSS”. Then, Hugo Boss filed the cancellation suit against the Trial Decision before the IP High Court. The IP High Court also decided that the trademarks “COOL BOSS” and “BOSS/HUGO BOSS” were not similar (§4-1-11 of the TM Law). However, the IP High Court cancelled the Trial Decision because the trademark “COOL BOSS” was liable to cause confusion with the goods manufactured by Hugo Boss since the cited trademark “BOSS” was well known in Japan for men’s clothing and men’s articles (§4-1-15 of the TM Law). On the other hand, the trademark “COOL BOSS” was used for the working wear with the small fan for ventilation and therefore, the word “COOL” in the trademark “COOL BOSS” was descriptive of goods and the word “BOSS” of the trademark was functioning as the trademark indicating the place of origin. As the result, the trademark “COOL BOSS” was liable to cause confusion with the goods by Hugo Boss. We disagree with this Court Decision because the men’s wear by Hugo Boss is highly-sophisticated and expensive in comparison with the working wear. -

MMM Investor Day 3.29.16 Transcript

3 2016 Investor Day Transcript March 29, 2016 Slide 1, Opening Bruce Jermeland, Director – Investor Relations Good morning. I am Bruce Jermeland, Director of Investor Relations, for those that I didn't meet last night. Welcome to 3M's Customer Innovation Center. We had a very good turn out last night at our new R&D facility on our campus, the 3M Carlton Science Center. Hopefully you got to learn more about 3M and also got an opportunity to interact with our leadership team. A number of those leaders will be speaking this morning. Of course we'll hear from Inge Thulin, our CEO, and Nick Gangestad, our CFO. But you'll also hear from all of our business group leaders, Mike Vale, Frank Little, Mike Roman, Joaquin Delgado and Jim Bauman. And you also hear from H.C. Shin, Head of our International Operations, and Paul Keel, Head of Supply Chain. Slide 2, Upcoming Events Bruce Jermeland Just a quick update on upcoming events in 2016. Four weeks from today, we'll have our first-quarter earnings announcement. Then the Q3 and Q4 earnings dates will be July 26 and October 25. And in December we will have our 2017 outlook meeting on December 13. Please mark your calendars. Slide 3, Today’s Agenda Bruce Jermeland Today's agenda, we will conclude formal presentations at about 11:45 and then have 45 minutes of Q&A. We will have a break about halfway through. After we wrap up Q&A, we'll have lunch downstairs where we had breakfast this morning. -

Discussion Guide DVD, Seeing Forward: Succession Planning at 3M

Read This First! Thank you for using the SHRM Foundation Discussion Guide DVD, Seeing Forward: Succession Planning at 3M. This document outlines the suggested use and explanation of the supplemental materials cre- ated for use with the video. Please read it carefully before proceeding. Our goal is to provide you, the facilitator, with materials that will allow you to create a custom- ized presentation and discussion. For this reason, we have included this Discussion Guide docu- ment. In addition, discussion question slides from the PowerPoint can be deleted to customize your presentation and discussion. Suggested Program Agenda 1. Distribute the Discussion Questions to participants and suggest that they watch the DVD with the questions in mind. 2. Play the DVD. 3. Use the PowerPoint introductory slides (Slides 2 through 7) to discuss the DVD, the history of 3M, and the 5 important lessons presented at the end of the DVD. 4. Distribute the Participant Worksheets to generate individual thought and discussion. (Alter- natively, these worksheets can also be used to assign group activities and continue with Step 5 after the activity, or they can be used after Step 5 to assess participant understanding. Please see the Participant Worksheet section below for more information.) 5. Use the PowerPoint question slides (Slides 8 through 26) to discuss each individual primary discussion question. (The Question Guide provides the facilitator with all necessary informa- tion and answers to lead a comprehensive discussion.) 6. Distribute the Participant Worksheet Answer Keys to participants. Supplemental Materials Descriptions 3M Overview The 3M Overview can be used as either a facilitator guide or a participant handout. -

Ornithologists Have Used Scotch Tape to Cover Cracks in Shells of Pigeon Eggs, Allowing the Eggs to Hatch

Ornithologists Have Used Scotch Tape To Cover Cracks In Shells Of Pigeon Eggs, Allowing The Eggs To Hatch. It could be a sticky situation on May 27th as we recognize National Cellophane Tape Day. It is hard to imagine where we would be without this invention. How would we wrap our Christmas and birthday gifts? This everyday household and office item is also known as invisible tape or Scotch Tape. Richard Gurley Drew invented the invisible tape in 1930. He created the tape from cellulose and originally called it cellulose tape. His career started at the 3M company in 1920 in St. Paul, Minnesota where he developed a masking tape for the automotive industry in 1925. Originally designed to seal Cellophane packages sold in groceries and bakeries, the new adhesive missed its mark. By the time all its drawbacks were resolved, DuPont introduced heat-sealed cellophane. Regardless, with a resounding endorsement from customers, 3M found a market in both the home and the office. The first brand of cellophane tape was developed by Richard Drew, and was called “Scotch” tape and now bears a very recognizable trademark of a red, black, and green tartan pattern. The name Scotch Tape actually resulted from an ethnic slur foisted upon manufacturers of the tape—although the product does not have any connection with Scotland or the Scottish. The term came about when a body shop painter who was testing one of the first tapes and announced in frustration “Take this tape back to those Scotch bosses of yours and tell them to put more adhesive on it!” Scotch at the time being a slang term for ‘stingy’. -

Bg-2016-488-Supplement.Pdf

Supplementary information An economical apparatus for the observation and harvesting of mineral precipitation experiments with light microscopy 5 Supplement A: Setup block & adaptor construction Note: The width and length of the setup block and adaptor should be slightly smaller than the long coverslip. The dimensions shown in Fig. 1 assume a standard long coverslip size of 24 x 60 mm. The bore diameter should be ~3–4 mm less than a side of the square coverslip. The bore size shown in Fig. 1 assumes an 18 x 18 mm square coverslip. Revise the dimensions as required to accommodate differently sized cover slips. 10 Setup block Machine the setup block as indicated in Fig. 1a. Adaptor 15 material needed ❑ two clear, rigid flat surfaces (“sheets”) such as 8 x 10 inch acrylic or glass sheets ❑ two microscope slides (of same thickness) ❑ one square coverslip ® ❑ silicone epoxy molding material (Castin’Craft EasyMold silicone putty, or similar) 20 ❑ cutting blade, such as an X-acto® blade or similar ❑ hole punch, 5/8-inch (Recollections™, or similar) Molding procedure ❑ Position a square coverslip and two slides on one of the sheets as shown in Fig. S1a. The slides will serve as spacers to set 25 the thickness of the adaptor and their positioning isn’t critical, but they should be at least ~ 40 mm apart. The square coverslip will form an indent in the adaptor to accept a square coverslip in the assembled unit. ❑ Mix a small volume of silicone epoxy, per instructions. ❑ Form the epoxy into a cylinder and gently press it over the coverslip between the slides, avoiding air bubbles under the epoxy. -

Multifunctional Epidermal Electronics Printed Directly Onto the Skin

MULTI-FUNCTIONAL ELECTRONICS Health-monitoring devices that can be mounted onto the human skin are of great medical interest. On page 2773, John A. Rogers and co-workers present materials and designs for electronics and sensors that can be conformally and robustly integrated onto the surface of the skin. This image shows an epidermal electronic system of ser- pentine traces that is directly printed onto the skin with conformal lamination. AADMA-25-20-Frontispiece.inddDMA-25-20-Frontispiece.indd 1 001/05/131/05/13 110:210:21 PPMM www.advmat.de www.MaterialsViews.com COMMUNICATION Multifunctional Epidermal Electronics Printed Directly Onto the Skin Woon-Hong Yeo , Yun-Soung Kim , Jongwoo Lee , Abid Ameen , Luke Shi , Ming Li , Shuodao Wang , Rui Ma , Sung Hun Jin , Zhan Kang , Yonggang Huang , and John A. Rogers * Health and wellness monitoring devices that mount on the of the skin without any mechanical constraints, thereby estab- human skin are of great historical and continuing interest in lishing not only a robust, non-irritating skin/electrode contact clinical health care, due to their versatile capabilities in non- but also the basis for intimate integration of diverse classes of invasive, physiological diagnostics. [ 1–4 ] Conventional technolo- electronic and sensor technologies directly with the body. The gies for this purpose typically involve small numbers of point present work extends these ideas through the development contact, fl at electrode pads that affi x to the skin with adhesive of signifi cantly thinner (by 20–30 times) variants of EES and tapes and often use conductive gels to minimize contact imped- of materials that facilitate their robust bonding to the skin, in ances. -

Download Transcript

Virtual Signature Event Mike Roman Chairman and Chief Executive Officer 3M David M. Rubenstein President The Economic Club of Washington, D.C. Wednesday, March 17, 2021 ANNOUNCER: Please welcome David Rubenstein, president of The Economic Club of Washington, D.C. DAVID M. RUBENSTEIN: Welcome, everybody, to our program today, on St. Patrick’s Day. I want to welcome you to our 15th Virtual Signature Event of our 35th season. We’re also marking a one-year mark of COVID-19. It was on February 24th of last year that we had our last in-person event. And by March the 11th we had pivoted to virtual events. We’ve now hosted 26 events and I’ve had interviews with over 80 individuals during this period of time. So we’ve tried the best we can to keep you informed about what’s going on in the business world and the social world in terms of other outside activities that are – that are important to the country. And we hope that you’ve appreciated and enjoyed these events. And I want to thank The Economic Club of Washington team, particularly Mary Brady, for leading this effort to get all these things – all this work organized, because it’s not easy to do virtual events, actually, right? Much harder than doing them in person, in many ways. Our special guest today, Mike Roman, has a very interesting background. Mike was – grew up in Wisconsin, a high school football star. He ultimately went to University of Minnesota, where he majored in electrical engineering, then he got a master’s in electrical engineering at University of Southern California. -

Crosby and Bailey2017

Supplement of Biogeosciences, 14, 2151–2154, 2017 http://www.biogeosciences.net/14/2151/2017/ doi:10.5194/bg-14-2151-2017-supplement © Author(s) 2017. CC Attribution 3.0 License. Supplement of Technical note: an economical apparatus for the observation and harvest of mineral precipitation experiments with light microscopy Chris H. Crosby and Jake V. Bailey Correspondence to: Chris H. Crosby ([email protected]) The copyright of individual parts of the supplement might differ from the CC-BY 3.0 licence. Diffusion gel material and solution concentrations can be altered as required for different experiments, but the conditions under which this apparatus was developed, and those used to produce figure 1E, are as follows: ❑ gelatin: type A, 1 g/ml water, pH ~4 2+ 5 ❑ cation solution: 0.133 M Ca [CaCl2•2H2O, pH ~8] 3– ❑ anion solution: 0.08 M (PO4) [NaHPO4, pH ~8] – ❑ anion solution: 0.027 M F [KF•2H2O, pH ~8] Nascent precipitation is observed within ~30 hours. 10 S1 Supplement A: Setup block & adaptor construction Note: The width and length of the setup block and adaptor-spacer should be slightly smaller than the long coverslip. The dimensions shown in Fig. 1 assume a standard long coverslip size of 24 x 60 mm. The bore diameter should be ~3–4 mm less than a side of the square coverslip. The bore size shown in Fig. 1 assumes an 18 x 18 mm square coverslip. Revise the 15 dimensions as required to accommodate differently sized cover slips. S1.1 Setup block Machine the setup block as indicated in Fig.