Draft Green Fort Conservation Plan

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

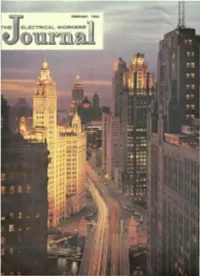

Electrical Workers'

FEBRUARY. 1963 ELECTRICAL WORKERS' O UR GOVERNMENT WORKERS The I nternational Brotherhood of Electrical Workers has a significant segment of its membership-about 3O,OOO- working for "Uncle Sam." There IS hardly an agency of the Federal Government which does not need trained Electrical Workers to adequately carry out its purposes, and of course in some branches of Government their work is vital. In Shipyards, Naval Ordnancp. Plants, in various defense activities for example, electricians, linemen, power plant electricians, electronics, fire control, gyro and radio technical mechanics, electric crane operators, and others, are essential in carrying on the work of defending our nation and keeping its people safe. 18EW members work on board ships, on all types of transmission lines, in all kinds of shops, as mainlerlcllu.:;e rnell servicing Federal buildings and equipment, on communications work of every type. You will find them employed by the Army. the Navy, the Coast Guard, the Air Force, the Marine Corps, General Services Administration, the Federal Aviation Agency, Veterans Administration, Bureau of Reclamation, Bureau of Indian Affairs, National Park Service, Census Bureau, Alaskan Railroad, Department of I nternal Revenue, Post Office Department, just to name a few. Of course the extensive work of IBEW members on such installations as the Tennessee Valley Authoritv. Bonneville Power and other Government projects throughout the country, is extremely well known. We could not mail a letter or spend a dollar bill if it were not for the Electrical Workers who keep the electronic machinery for printing stamps and currency in good running order, in the Bureau of Printing and Engraving. -

The Early Effects of Gunpowder on Fortress Design: a Lasting Impact

The Early Effects of Gunpowder on Fortress Design: A Lasting Impact MATTHEW BAILEY COLLEGE OF THE HOLY CROSS The introduction of gunpowder did not immediately transform the battlefields of Europe. Designers of fortifications only had to respond to the destructive threats of siege warfare, and witnessing the technical failures of early gunpowder weaponry would hardly have convinced a European magnate to bolster his defenses. This essay follows the advancement of gunpowder tactics in late medieval and early Renaissance Europe. In particular, it focuses on Edward III’s employment of primitive ordnance during the Hundred Years’ War, the role of artillery in the Ottoman conquest of Constantinople, and the organizational challenges of effectively implementing gunpowder as late as the end of the fifteenth century. This essay also seeks to illustrate the nature of the development of fortification in response to the emerging threat of gunpowder siege weaponry, including the architectural theories of the early Renaissance Italians, Henry VIII’s English artillery forts of the mid-sixteenth century, and the evolution of the angle bastion. The article concludes with a short discussion of the longevity and lasting relevance of the fortification technologies developed during the late medieval and early Renaissance eras. The castle was an inseparable component of medieval warfare. Since Duke William of Normandy’s 1066 conquest of Anglo-Saxon England, the construction of castles had become the earmark of medieval territorial expansion. These fortifications were not simply stone squares with round towers adorning the corners. Edward I’s massive castle building program in Wales, for example, resulted in fortifications so visually disparate that one might assume they were from different time periods.1 Medieval engineers had built upon castle technology for centuries by 1500, and the introduction of gunpowder weaponry to the battlefields of Europe foreshadowed a revision of the basics of fortress design. -

Galway City Walls Conservation, Management and Interpretation Plan

GALWAY CITY WALLS CONSERVATION, MANAGEMENT & INTERPRETATION PLAN MARCH 2013 Frontispiece- Woman at Doorway (Hall & Hall) Howley Hayes Architects & CRDS Ltd. were commissioned by Galway City Coun- cil and the Heritage Council to prepare a Conservation, Management & Interpre- tation Plan for the historic town defences. The surveys on which this plan are based were undertaken in Autumn 2012. We would like to thank all those who provided their time and guidance in the preparation of the plan with specialist advice from; Dr. Elizabeth Fitzpatrick, Dr. Kieran O’Conor, Dr. Jacinta Prunty & Mr. Paul Walsh. Cover Illustration- Phillips Map of Galway 1685. CONTENTS 1.0 INTRODUCTION 1 2.0 UNDERSTANDING THE PLACE 6 3.0 PHYSICAL EVIDENCE 17 4.0 ASSESSMENT & STATEMENT OF SIGNIFICANCE 28 5.0 DEFINING ISSUES & VULNERABILITY 31 6.0 CONSERVATION PRINCIPLES 35 7.0 INTERPRETATION & MANAGEMENT PRINCIPLES 37 8.0 CONSERVATION STRATEGIES 41 APPENDICES Statutory Protection 55 Bibliography 59 Cartographic Sources 60 Fortification Timeline 61 Endnotes 65 1.0 INTRODUCTION to the east, which today retains only a small population despite the ambitions of the Anglo- Norman founders. In 1484 the city was given its charter, and was largely rebuilt at that time to leave a unique legacy of stone buildings The Place and carvings from the late-medieval period. Galway City is situated on the north-eastern The medieval street pattern has largely been shore of a sheltered bay on the west coast of preserved, although the removal of the walls Ireland. It is located at the mouth of the River during the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, Corrib, which separates the east and western together with extra-mural developments as the sides of the county. -

Fort Union Trading Post National Historic Site Fort Union Trading Post National Historic Site Table of Contents

National Park Service Cultural Landscapes Inventory 2012 Fort Union Trading Post National Historic Site Fort Union Trading Post National Historic Site Table of Contents Inventory Unit Summary & Site Plan Concurrence Status Geographic Information and Location Map Management Information National Register Information Chronology & Physical History Analysis & Evaluation of Integrity Condition Treatment Bibliography & Supplemental Information Fort Union Trading Post National Historic Site Fort Union Trading Post National Historic Site Inventory Unit Summary & Site Plan Inventory Summary The Cultural Landscapes Inventory Overview: CLI General Information: Purpose and Goals of the CLI The Cultural Landscapes Inventory (CLI), a comprehensive inventory of all cultural landscapes in the national park system, is one of the most ambitious initiatives of the National Park Service (NPS) Park Cultural Landscapes Program. The CLI is an evaluated inventory of all landscapes having historical significance that are listed on or eligible for listing on the National Register of Historic Places, or are otherwise managed as cultural resources through a public planning process and in which the NPS has or plans to acquire any legal interest. The CLI identifies and documents each landscape’s location, size, physical development, condition, landscape characteristics, character-defining features, as well as other valuable information useful to park management. Cultural landscapes become approved CLIs when concurrence with the findings is obtained from the park superintendent and all required data fields are entered into a national database. In addition, for landscapes that are not currently listed on the National Register and/or do not have adequate documentation, concurrence is required from the State Historic Preservation Officer or the Keeper of the National Register. -

Records Relating to Railroads in the Cartographic Section of the National Archives

REFERENCE INFORMATION PAPER 116 Records Relating to Railroads in the Cartographic Section of the national archives 1 Records Relating to Railroads in the Cartographic Section of the National Archives REFERENCE INFORMATION PAPER 116 National Archives and Records Administration, Washington, DC Compiled by Peter F. Brauer 2010 United States. National Archives and Records Administration. Records relating to railroads in the cartographic section of the National Archives / compiled by Peter F. Brauer.— Washington, DC : National Archives and Records Administration, 2010. p. ; cm.— (Reference information paper ; no 116) includes index. 1. United States. National Archives and Records Administration. Cartographic and Architectural Branch — Catalogs. 2. Railroads — United States — Armed Forces — History —Sources. 3. United States — Maps — Bibliography — Catalogs. I. Brauer, Peter F. II. Title. Cover: A section of a topographic quadrangle map produced by the U.S. Geological Survey showing the Union Pacific Railroad’s Bailey Yard in North Platte, Nebraska, 1983. The Bailey Yard is the largest railroad classification yard in the world. Maps like this one are useful in identifying the locations and names of railroads throughout the United States from the late 19th into the 21st century. (Topographic Quadrangle Maps—1:24,000, NE-North Platte West, 1983, Record Group 57) table of contents Preface vii PART I INTRODUCTION ix Origins of Railroad Records ix Selection Criteria xii Using This Guide xiii Researching the Records xiii Guides to Records xiv Related -

A Contemporary Map of the Defences of Oxford in 1644

A Contemporary Map of the Defences of Oxford in 1644 By R. T. LATTEY, E. J. S. PARSONS AND I. G. PHILIP HE student of the history of Oxford during the Civil War has always been T handicapped in dealing with the fortifications of the City, by the lack of any good contemporary map or plan. Only two plans purporting to show the lines constructed during the years 1642- 6 were known. The first of these (FIG. 24), a copper-engraving in the 'Wood collection,! is sketchy and ill-drawn, and half the map is upside-down. The second (FIG. 25) is in the Latin edition of Wood's History and Antiquities of the University of Oxford, published in 1674,2 and bears the title' Ichnographia Oxonire una cum Propugnaculis et Munimentis quibus cingebatur Aimo 1648.' The authorship of this plan has been attributed both to Richard Rallingson3 and to Henry Sherburne.' We know that Richard Rallingson drew a' scheme or plot' of the fortifications early in 1643,5 and Wood in his Athenae Oxomenses 6 states that Henry Sherburne drew' an exact ichno graphy of the city of Oxon, while it was a garrison for his Majesty, with all the fortifications, trenches, bastions, etc., performed for the use of Sir Thomas Glemham 7 the governor thereof, who shewing it to the King, he approved much of it, and wrot in it the names of the bastions with his own hand. This ichnography, or another drawn by Richard Rallingson, was by the care of Dr. John Fell engraven on a copper plate and printed, purposely to he remitted into Hist. -

Village Board Meeting Packet: July 6, 2021

VILLAGE OF ALGONQUIN VILLAGE BOARD MEETING July 6, 2021 7:30 p.m. 2200 Harnish Drive -AGENDA- 1. CALL TO ORDER 2. ROLL CALL – ESTABLISH QUORUM 3. PLEDGE TO FLAG 4. ADOPT AGENDA 5. AUDIENCE PARTICIPATION (Persons wishing to address the Board, if in person must register with the Village Clerk prior to call to order.) 6. APPOINT JOSEPH “JOE” MENOLASCINO TO THE ECONOMIC DEVELOPMENT COMMISSION (All Appointments Require the Advice and Consent of the Village Board) 7. CONSENT AGENDA/APPROVAL: All items listed under Consent Agenda are considered to be routine by the Village Board and may be approved and/or accepted by one motion with a voice vote. A. APPROVE MEETING MINUTES: (1) Liquor Commission Special Meeting Held June 15, 2021 (2) Village Board Meeting Held June 15, 2021 (3) Committee of the Whole Meeting Held June 15, 2021 (4) Committee of the Whole Special Meeting Held June 22, 2021 8. OMNIBUS AGENDA/APPROVAL: The following Ordinances, Resolutions, or Agreements are considered to be routine in nature and may be approved by one motion with a roll call vote. (Following approval, the Village Clerk will number all Ordinances and Resolutions in order.) A. ADOPT RESOLUTIONS: (1) Pass a Resolution Accepting and Approving an Agreement with Utility Service Co. Inc. for the Countryside Standpipe Maintenance Program in the Amount of $560,078.00 (2) Pass a Resolution Accepting and Approving an Agreement with Christopher Burke Engineering for the Design/Build of the Dry Utility Relocation Project in the Amount of $204,358.00 (3) Pass a Resolution Accepting -

National Register of Historic Places Registration Form

NPS Form 10-900 OMB No. 1024-0018 United States Department of the Interior National Park Service National Register of Historic Places Registration Form This form is for use in nominating or requesting determinations for individual properties and districts. See instructions in National Register Bulletin, How to Complete the National Register of Historic Places Registration Form. If any item does not apply to the property being documented, enter "N/A" for "not applicable." For functions, architectural classification, materials, and areas of significance, enter only categories and subcategories from the instructions. 1. Name of Property Historic name: Staunton River Bridge Fortification Historic District Other names/site number: Fort Hill: Staunton River Battlefield State Park; DHR #041-5276 Name of related multiple property listing: The Civil War in Virginia, 1861–1865: Historic and Archaeological Resources________ (Enter "N/A" if property is not part of a multiple property listing ____________________________________________________________________________ 2. Location Street & number: 1035 Fort Hill Trail__________________________________________ City or town: _Randolph___ State: Virginia County: Halifax and Charlotte_____ Not For Publication: x Vicinity: x ____________________________________________________________________________ 3. State/Federal Agency Certification As the designated authority under the National Historic Preservation Act, as amended, I hereby certify that this x nomination ___ request for determination of eligibility -

10 Ivanisevic.Qxd

UDC 904:725.96 »653« (497.115) 133 VUJADIN IVANI[EVI], PERICA [PEHAR Institute of Archaeology, Belgrade EARLY BYZANTINE FINDS FROM ^E^AN AND GORNJI STREOC (KOSOVO) Abstract. – In this article, we presented the archaeological finds from ^e~an and Gornji Streoc – hill-forts on Mount ^i~evica in the immediate vicinity of Vu~itrn (Kosovo). We studied the archaeological material from the Roman, Late Roman and, in particular from the Early Byzantine period. A large number of archaeological objects and especially iron tools found on the ^e~an and Gornji Streoc fortresses indicate a well-developed level of production in the crafts and iron manufacturer. We emphasize the importance of these fortresses in Late Roman times and we highlight the fortification of the interior regions of Illyricum. This suggests that Dardania had a considerable population in the Late Roman period as is confirmed by the many fortresses constructed throughout the entire region, often on almost inaccessible terrain. Key words. – Dardania, Kosovo, Fortifications, Late Roman, Early Byzantine, Finds, Coins. ery little is known about the material culture abounding in pastures and intersected by fertile river of Kosovo in Late Roman times. Thus, the valleys, were favourable for the development of agri- V period from the tetrarchy to the time of culture and cattle-raising. The mountain chains, rich in Heraclius is represented with very few finds in the primary deposits of copper, iron and silver ore contri- catalogue of the exhibition Arheolo{ko blago Kosova i buted to the development of mining as an important Metohije (Archaeological treasures of Kosovo and economic activity in Dardania.4 Trading also played a Metohija). -

Chapter 2 Yeardley's Fort (44Pg65)

CHAPTER 2 YEARDLEY'S FORT (44PG65) INTRODUCTION In this chapter the fort and administrative center of Flowerdew at 44PG65 are examined in relation to town and fortification planning and the cultural behavior so displayed (Barka 1975, Brain et al. 1976, Carson et al. 1981; Barka 1993; Hodges 1987, 1992a, 1992b, 1993; Deetz 1993). To develop this information, we present the historical data pertaining to town development and documented fortification initiatives as a key part of an overall descriptive grid to exploit the ambiguity of the site phenomena and the historic record. We are not just using historic documents to perform a validation of archaeological hypotheses; rather, we are trying to understand how small-scale variant planning models evolved regionally in a trajectory away from mainstream planning ideals (Beaudry 1988:1). This helps refine our perceptions of this site. The analysis then turns to close examination of design components at the archaeological site that might reveal evidence of competence or "mental template." These are then also factored into a more balanced and meaningful cultural interpretation of the site. 58 59 The site is used to develop baseline explanatory models that are considered in a broader, multi-site context in Chapter 3. Therefore, this section will detail more robust working interpretations that help lay the foundations for the direction of the entire study. In short, learning more about this site as a representative example of an Anglo-Dutch fort/English farmstead teaches us more about many sites struggling with the same practical constraints and planning ideals that Garvan (1951) and Reps (1972) defined. -

Anatomising Irish Rebellion: the Cromwellian Delinquency Commissions, the Books of Discrimination and the 1641 Depositions

Anatomising Irish Rebellion: the Cromwellian Delinquency Commissions, the Books of Discrimination and the 1641 Depositions Cunningham, J. (2016). Anatomising Irish Rebellion: the Cromwellian Delinquency Commissions, the Books of Discrimination and the 1641 Depositions. Irish Historical Studies, 40(157), 22-42. https://doi.org/10.1017/ihs.2016.3 Published in: Irish Historical Studies Document Version: Peer reviewed version Queen's University Belfast - Research Portal: Link to publication record in Queen's University Belfast Research Portal Publisher rights © 2016 Irish Historical Studies Publications Ltd. This work is made available online in accordance with the publisher’s policies. Please refer to any applicable terms of use of the publisher. General rights Copyright for the publications made accessible via the Queen's University Belfast Research Portal is retained by the author(s) and / or other copyright owners and it is a condition of accessing these publications that users recognise and abide by the legal requirements associated with these rights. Take down policy The Research Portal is Queen's institutional repository that provides access to Queen's research output. Every effort has been made to ensure that content in the Research Portal does not infringe any person's rights, or applicable UK laws. If you discover content in the Research Portal that you believe breaches copyright or violates any law, please contact [email protected]. Download date:01. Oct. 2021 1 Anatomising Irish rebellion: the Cromwellian delinquency commissions, the books of discrimination and the 1641 depositions In the early 1650s the ability of the Cromwellian government in Ireland to implement many of its preferred policies was severely threatened by an acute information deficit relating to the 1641 rebellion and its aftermath. -

Iaterford 4 South-East of Ireland

JOURNAL OF THE IATERFORD 4 SOUTH-EAST OF IRELAND ?VXTERFOIID : PRINTED FOR THE SOCIETY BY HARVEY & CO. CONTENTS, Page ANNUAL MEETING, 1900 ... ... ... ... ix, Thc Kings of Ancient Ireland ; Their Number, Rights, Election and Inauguration. By Rev. J. Mocltler ... I Notcs relating to the Manor of Rallygunner, Co. Waterford. By Williain H. Graitan Flood, M.ILS.A. .,. ... 17 Antiquiiies irom Kilkenny City to Kilcooley Abbey. By Rev. W. Healy, P.P., P.~z.s.A. .. ... .,. 2 I Liscarroll Castle and Ba1lybc.g Abbey. ?3y Rev. C. Bucklcy ... 32 The Old Gun found in River Suir, January 1901, By Major 0. Wheeler Cuffe, M. R.S. A. ... ... ... 36 Waterford and South-Eastern Counties' Early Priniecl Books, Newspapers, etc. By James Coleman ... ... 39, 136, 181 NOTES AND QUERIES .. ... *9*41,971I391 181 Ancient Guilds or Fraternities of the County of the City of Waterford. Hy Patrick Higgins, ~.n,s,A. ... .. 6 I Lismore during the Reign of Henry VIII. By Williain H. Grattan Flood, M:R.S,A. ... ... ... 66 Lismore during the Reign of Edward V1 and Queen Mary. By William H. Grattan Flood, M.R.S.A. .. .. 124 Lisinore during the Reign oi Queen Elizabeth. By Willam H, Grattan Flood, M.I<.S.A. .. ... ... 156 Don Philip O'Sullivan ; The Siege of D~ulboy,ancl the Retreat ancl Assassination of O'SuLlivan Beare ... 76, 103 Old ancl New Ross (Eclitccl by Philip H. Hore, hi.I<.I.A,, M. I<.S.A.I.). Rcview by the Hon. Editor ... ... 132 A Forgotten Waterford Worthy, By J. Colcman, M,R,S.A. ... I43 Tracts Illustrative of the Civil War in Ireland of 1641, etc.